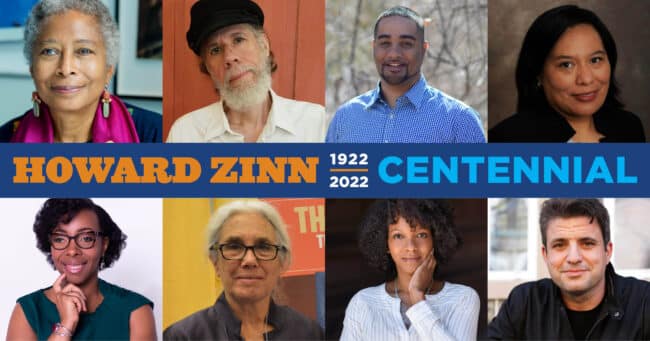

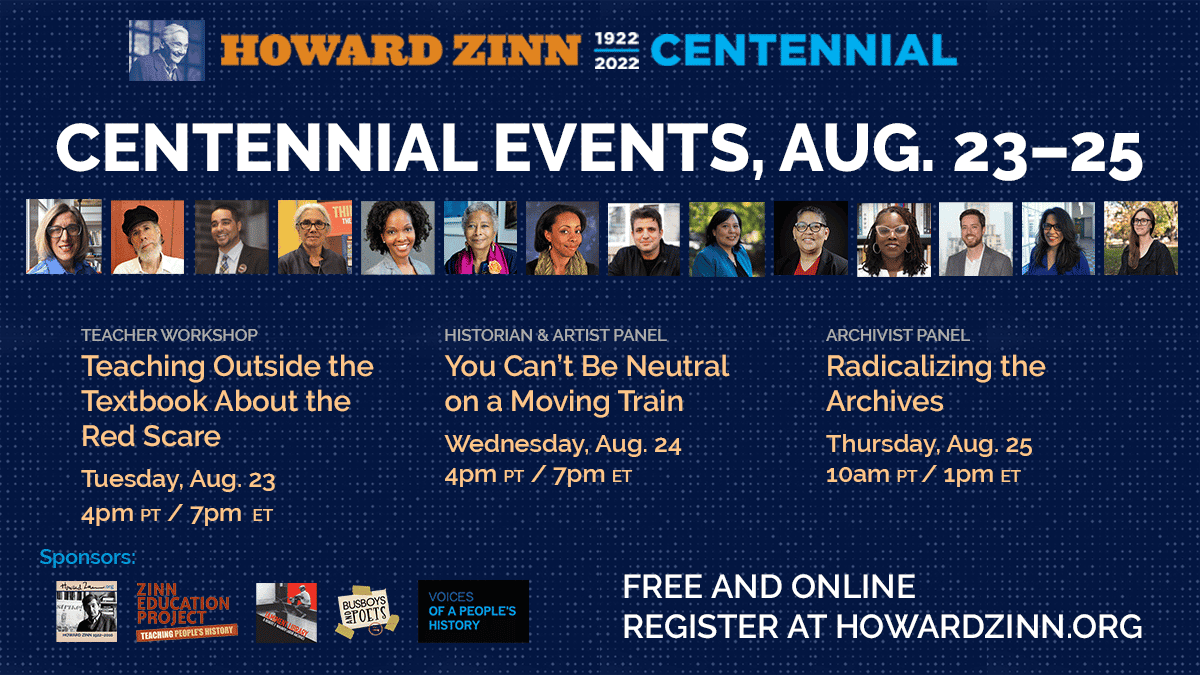

On Wednesday, August 24, 2022, we hosted an event with special guests to commemorate Howard Zinn (1922–2010) and other people’s historians. The event was held on the 100th anniversary of Zinn’s birth and the theme was from the title of his biography, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train.

Sports historian Dave Zirin and Teaching for Black Lives co-editor Jesse Hagopian were the MC’s. The guest speakers were Martín Espada, Kidada E. Williams, Myla Kabat-Zinn, Imani Perry, Alice Walker, Lauren Cooper, Bill Bigelow, and Anthony Arnove. The event was co-sponsored by the Howard Zinn Trust, Tamiment Library at New York University, and Busboys and Poets.

Jesse Hagopian opened the event by inviting everyone to participate.

This is a people’s history event, so please introduce yourself in the chat. Add a note about your connection to Howard Zinn or to A People’s History.

You can talk about the struggles you’re involved in today, the struggles that are happening all over the country. I wish Howard Zinn could see the Starbucks workers who are organizing unions right now. I wish he was here to see the historic victory for the Amazon organizing of warehouse workers, the 2020 uprising for Black lives, and all the educator strikes that have happened around the country. All these struggles that I know many of you probably have been a part of or have supported in some way.

While it was a virtual event, the energy in “the room” was dynamic. The attendees came to hear the speakers and be in community with each other for this birthday party. They included teachers, former students of Howard Zinn’s, historians, and more. To give a sense of the range of people in attendance, here are some of their introductions from the chat:

Emily Kavanagh, MS SPED social studies self-contained teacher in Annapolis, MD, but from Columbia, MD.

Gregory Lopez, English teacher. Day 2.

Marya Fonsh-Mielinski, kindergarten interventionist, Massachusetts. My dad was a social studies teacher — Zinn was a household name.

Ciera Alvarez, Humboldt CA, budding elementary teacher.

Kimberlee Rackley, community educator, home educator, former public school educator, Sandy Hook, CT.

Ed Herbert, met Howard once, so optimistic and insightful. Wish he was still with us now.

Chris Martell, UMass Boston, long-time teacher of Zinn’s work. Once met him when he visited the high school where I previously taught.

Laura Zinn, I am Howard Zinn’s niece and my sister Carla is also joining.

Miguel López, from CA. I had a chance to work with Howard during a summer back in the early 2000s, and I’m teaching his work this semester in a course on social justice in public schooling.

Rachel Bernstein, historian, LaborArts.org, working on a project celebrating the 1982 Chinatown garment workers’ strike anniversary.

Mindy Stone, I thank Howard Zinn for introducing me to Emma Goldman in 2003 who changed my life forever and for better!

Dean Stevens, music director and programmer, Community Church of Boston, a Peace and Justice Congregation, where Howard spoke at least a dozen times over a period of 35 years. In 2000, we awarded Howard with our annual Sacco and Vanzetti Award for Social Justice. We will celebrate Howard’s life on a Sunday in December by playing excerpts of recordings from his many talks from our pulpit. I got arrested with Howard, Noam, and 500 others at the JFK Building in Boston on May 1, 1985, protesting U.S. war on Nicaragua. Honored to be here.

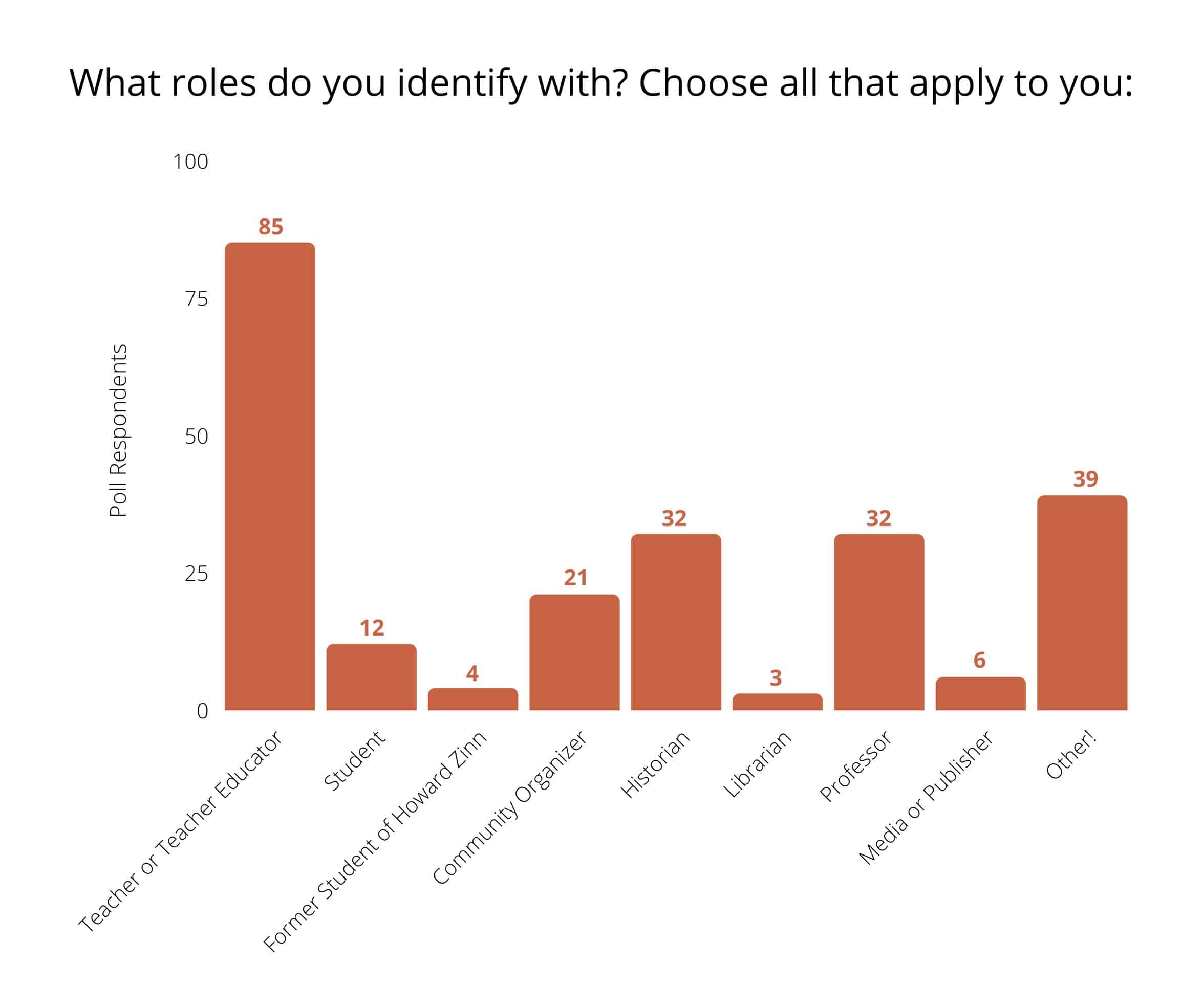

Jesse invited attendees to respond to a poll about the hats they wore, selecting as many categories as applied.

Jesse added, “We are very honored to be joined this evening by Howard Zinn’s family members and by former students of his at Spelman College and at Boston University.”

Recording and Transcript

Following are a transcript, a video, and an audio recording of the two-hour event. There are also separate clips of each speaker.

And so now we want to conduct a poll to find out who’s in the room. Do we have any teachers in the house? Former students of Howard Zinn, SNCC veterans, professors, community organizers, students, librarians, educators of all kind. Please check as many boxes as apply, so we can find out who is with us this evening for this celebration of Howard Zinn’s life. Howard would have been one hundred years old today. Happy birthday, Howard!

Look at these numbers coming in, just as people are taking the poll. It looks like we have a whole lot of incredible people, sixty two percent teachers or teacher educators. We have former students of Howard Zinn’s in the house. We have professors, community organizers, and students with us today. It would have made Howard very happy to have the youth here. Librarians, historians, we have members of the media and publishers here, and all the rest of you. All the people are in the house tonight.

I want to begin by just sharing a short story about the importance of the book A People’s History to me before I turn it over to Dave to share a story, as well.

I want to begin by telling a story from my first two years teaching high school. When the great recession hit, I was laid off along with hundreds of teachers in Seattle and thousands of teachers across the country, and they said there was no money to keep the education system running. There was just enough money to bail out the culprits who had sabotaged the global economy with credit default swaps and collateralized debt obligations, but not enough for kids and for education.

And then in 2010, the same year that Howard Zinn passed away, I was hired to teach at my alma mater, Garfield High School, and I was teaching AP U.S. History, and they wanted me to teach to the test in order to have these kids pass the AP exam. But I threw out that garbage, and instead, I used A People’s History as my textbook, and I used the lessons from the Zinn Education Project website: lessons about the women’s suffrage movement and the abolitionist movement, lessons where students become members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and have to debate the actual issues that those activists debated in their own time.

Then the next year, the Washington State Legislature declared that they were going to cut many, many millions of dollars from the state education budget, even though our state constitution declares that education is “the paramount duty of the state.” So, a group of us social equity educators joined with Occupy activists, and we stormed the state capital. We took the advice of Howard Zinn when he said, “Our problem is not civil disobedience. Our problem is civil obedience. Our problem is the number of people all over the world who have obeyed the dictates of the leaders of their government.”

So we decided to disobey, and when they gaveled in the budget cutting session, I attempted a citizen’s arrest of the State Legislature complete with some gray plastic handcuffs I brought, and I asked the legislators to come into my custody. But the state trooper there didn’t agree with my interpretation of the law, and instead he arrested me, and I spent that day and evening in jail.

Then the next day, when I got to school, I found out that some of my students from the previous year who had engaged in a people’s history took credit for my release from jail because they started a Facebook page called “Free Mr. Hagopian.”

And then the most incredible thing happened. They transformed that Facebook page to a student group calling for a walkout against the budget cuts, and in the next day over five hundred students walked out of Garfield High School, marched down to City Hall, and they sparked a city-wide walkout movement that ultimately put enough pressure on the State Supreme Court to get them to rule, in the McCleary decision, to add literally billions of dollars to the state education budget. And I tell that story because I just want people to know that there are so many fights for justice that you’ve never heard of all over the country that were guided and aided by Howard Zinn’s work, and that’s really why the establishment is so scared.

Dave, you’re up.

Dave Zirin: Well, first of all, it’s great to be here. I have a lot of Howard Zinn stories given that I met him when I was nineteen in college, and at the end of Howard’s life, we actually did several events together where I would interview him on stage. I’ll be very brief.

I wanted to tell you about the time we did an event in December 2009. It was really just a month before Howard passed, and we did these events together because Howard’s mind was sharp as a tack. But he didn’t necessarily like standing for two hours to lecture and answer questions. So we would sit together on stage, and I would just throw him some softball questions like, “Racism. Your thoughts?” And Howard would speak for twenty or thirty minutes, and I would nod my head sagely.

And this event in December 2009, we walked into this church that easily seated seven or eight hundred people, and it was empty. I was scared as could be, and I looked at Howard, and Howard said to me, as if reading my face, he said, “Even if only a few people come, those will be the people we try to reach.” And that gets it, because if you think about all the quotes that Howard has said over the years about how small acts of resistance lead to big social movements, and even the actions of a few can eventually mushroom outward and make all the difference in the world. That was his approach to a public meeting, as well. So we go up on stage, and suffice it to say, the place is packed. It sat eight hundred, but the count was at about a thousand. I mean, people hanging off the rafters to see this event. And Howard looked at me, and we actually have a photo of him saying this to me where he’s smiling, and he says to me, “I guess we have more than a few people here.”

He was just in his sweet spot. The event was sponsored by the Campaign to End the Death Penalty, which I think just really highlights Howard’s lifelong commitment to anti-racism. The fact that this was a place he felt like he needed to be because he felt like the death penalty was racist to its very core. And the last thing I’ll say about that night is Howard stayed to sign things. Think about that: A meeting of a thousand people and he stayed to sign. And people were bringing up dog-eared copies of A People’s History like they’d been dropped in their tub a dozen times and then dried out with a hairdryer, and they’re walking these old copies of A People’s History for Howard to sign.

About a dozen times I went up to the table and said, “Are you done? Would you like to go? Are you tired?” He would not leave until every last person got a book signed because he knew the importance of these singular interactions. He might not remember them, but people were going to walk away and say, “Wow! I just had a moment with Howard Zinn!” That’s the sort of thing, when we speak about social movements that actually had a real effect on people, to feel connected to Howard because he wasn’t just a historian—he was the people’s historian.

Howard Zinn on Neutrality

Zirin: I’d like to introduce some clips of Howard speaking. The first one is about the theme for this event, “You can’t be neutral on a moving train.”

Zinn Transcript

Howard Zinn (video): Well, it came from — I stole it from myself. That is, I used to say that to my classes at the beginning of every class. I wanted to be honest with them about the fact that they were not entering a class where the teacher would be neutral. It was not going to be a class where the teacher spent a half year or a year with the students, and they would have no idea where the teacher stood on the important issues. This is not going to be a neutral class, I said. I don’t believe in neutrality.

I believe neutrality is impossible because the world is already moving in certain directions. Wars are going on. Children are starving. And to be neutral, to pretend to neutrality, to not take a stand in a situation like that is to collaborate with whatever is going on. To allow it to happen. I did not want to be a collaborator with what was happening. I wanted to enter into history. I wanted to play a role. I wanted my students to play a role.

I wanted us to intercede. I wanted my history to intercede and to take a stand on behalf of peace, on behalf of a racial equality or sexual equality, and so I wanted my students to know that right from the beginning, know you can’t be neutral on a moving train.

Howard Zinn’s Talk to Teachers

Zirin: Wow, there it is right there. We’ve got another clip that we really want to show. It’s a clip of Howard Zinn speaking to teachers, very appropriate for this event, and when people hear what Howard Zinn is saying to teachers, I want you to keep in mind that this is the message that they want banned from classrooms.

Zinn Transcript

Zinn (video): We’ve never had our injustices rectified from the top, from the president or Congress, or the Supreme Court, no matter what we learned in junior high school about how we have three branches of government, and we have checks and balances, and what a lovely system. No. The changes, important changes that we’ve had in history, have not come from those three branches of government. They have reacted to social movements.

Lincoln and Congress reacted to the anti-slavery movement. Congress and the president reacted to the labor movement. Roosevelt and FDR reacted to the strikes and the tenants’ movements, and the unemployed councils, and so on. In the civil rights years, Johnson and Kennedy, they were not saviors. They reacted to all those people, Black people and some white people, in the South who demonstrated and protested and went to jail, and some that were killed.

That’s what got the Civil Rights Act of ‘64 and the Voting Rights Act of ‘65. No saviors from the top, [that had never done], had always taken a peoples’ movement.

Bill Bigelow on the Zinn Education Project

Hagopian: So, what you just saw was a talk to teachers at the National Council for Social Studies in 2008, and this was part of the launch of the Zinn Education Project, which Howard co-founded. To say more on that, we are joined by Bill Bigelow, who will describe that for us. Welcome, Bill.

Bill Bigelow Transcript

Bill Bigelow: I first met Howard Zinn in 1992. I was doing a Rethinking Columbus workshop for teachers in Cambridge — and Howard showed up. It was as if Willie Mays had come to my little league game.

I think that Howard showed up for a reason. One of the things about people’s history for Howard Zinn is that he wasn’t concerned just with the history itself — he also wanted to support those of us in schools to figure out what it means to actually teach a people’s history.

Howard liked to say that “When I became a teacher, I had a very MODEST goal: I just wanted to change the world.”

No doubt, that’s a huge aspiration, but I think it’s true for a lot of teachers. We come out of grad school, filled with idealism — we want to help students think critically and deeply. We want to make the world a better place. But there is this huge chasm between our aspirations and our ability. And so often we just don’t have the resources.

That’s what Howard wanted to address when he and Bill Holtzman, his former student at BU, got together in 2007. They contacted Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change with the idea for the Zinn Education Project.

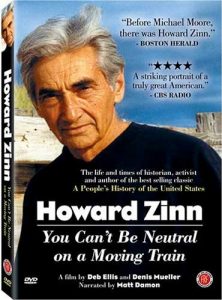

We began by giving teachers thousands of copies of A People’s History of the United States, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train — the film about Howard — and a teaching guide to help bring some of this history to life in the classroom.

We began by giving teachers thousands of copies of A People’s History of the United States, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train — the film about Howard — and a teaching guide to help bring some of this history to life in the classroom.

We wanted the Zinn Education Project website to be filled with stories — a place where teachers could find people’s history lesson plans, suggestions for novels, and films. And we invited teachers to share how they used these resources with students.

And teachers responded. That first year, 4,000 teachers registered to download lessons. Four years later, over 25,000 had registered. Today, about 150,000 teachers have signed up to align their social justice values with their classroom practice.

Two years ago, we launched a campaign on Teaching for Black Lives — including our Teach the Black Freedom Struggle classes. We also have campaigns to Abolish Columbus Day, Teach Reconstruction, and Teach Climate Justice.

These days, of course, Republicans are trying to bully social justice educators into silence. The Zinn Education Project is trying to help teachers fight back — organizing #TeachTruth demonstrations, helping folks find and support each other — offering more and more resources.

I interviewed Howard in January 2010, a week before he died. I ended the interview by asking him what advice he had for future history teachers. He said: “Don’t be intimidated by what they say you must teach. If you don’t take any risks, you’re not doing the right thing.”

That’s what we hope to do: Offer teachers the resources and community where they can take those risks.

In his autobiography, Howard wrote: “I am convinced of the uncertainty of history . . . of the possibility of surprise . . . of the importance of human action in changing what looks unchangeable.”

I think every teacher in the country should help our students grasp that truth.

Attacks on Teaching People’s History

Hagopian: Yes, thank you, Bill. Absolutely. I think because they can’t defeat Zinn’s arguments, they just really try to ban it all together. And we’ve seen this over and over and over again in Indiana in 2010, in Tucson in 2012, where they pulled books off the shelf in ethnic studies classes. Then they tried again in 2017 in Arkansas, and thankfully, a movement helped to defeat that. And then again, on September 17, 2020, President Trump hosted the White House Conference on American History, a gathering that was part dystopian novel, part farce, part tragedy, which featured a panel of memory hall historians who attempted to publicly destroy that inconveniently revealed structural racism. And then, in his opening remarks to this event, Trump said, “It’s gone too far. Our children are instructed from propaganda tracks like those of Howard Zinn. They try to make students ashamed of their own history.”

And then anti-people’s historian Allen Guelzo put a target on the back of the Zinn Education Project with the absurd lie that the organization’s materials are “snuck under the door of unsuspecting teachers” rather than the reality that tens of thousands of teachers are downloading these lessons all across the country. And so today we have some forty-two states that have introduced legislation or enacted policies that seek to require teachers to lie to students about structural racism or sexism or homophobia. But it is truly incredible to be part of a movement of honest educators and truth. Teachers who are fighting back. The Zinn Education Project has now helped organize three different national days of #TeachTruth. And if you look closely at this photo, on one of these national days of actions for #TeachTruth, you can see on this table that was organized by these students and teachers, a copy of A People’s History there. And I think there are many demonstrations all across the country where the same can be said.

Zirin: You just said a mouthful, Jesse. Thank you so much for that. But of course, as you well know from your work, the silencing of history goes way back and is deep in the marrow of this country. It has most often been done not with laws or crude thugs in the White House having their say, but simply by leaving history out of the textbooks and the curriculum.

Lauren Cooper

Our next guest is Lauren Cooper. We’re going to speak to Lauren about her own education and her work with Teaching for Change and the Howard Zinn Trust as digital curator for the Howard Zinn website. Lauren is also a librarian for the Center for Black Digital Research, and she was the founding staff coordinator for the Zinn Education Project. Hello, Lauren!

Lauren Cooper Transcript and Documents from the Archives

Lauren Cooper: Hello! Good evening, everyone.

Zirin: Great to see you. Thank you. So, Lauren, please tell us if you could, what about your own education led you to this work?

Cooper: I’m Native American, born and raised in Phoenix, Arizona. I’m Akimel O’Odham from the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona and Muskogee from the Creek Nation in Oklahoma, formerly of Georgia. Oklahoma has the highest Native population in the U.S. and Arizona has the third largest population with more than 20 tribal groups. So growing up, it seemed like Natives were everywhere! Everywhere, that is, except when it came to history class or contemporary media.

I remember growing up, sitting in an American History class, reading a couple of paragraphs about Natives who came and went during the westward expansion, relegating us to the past and framing us in the past tense, when clearly, we were sitting there in the room, yelling in our head, “We’re right here. We’re still alive!” But I would just sit there, enduring those history lessons about how the Indians lost, or foolishly gave up, their land for pennies or beads, or how they couldn’t defend themselves against the mighty U.S. military. Who wants to be associated with that: defeat, loss, weakness? It was just painful. I would just sit there waiting for the moment to pass. The textbooks just didn’t reflect what I saw around me. I found my sense of belonging in the politics of the punk rock scene and do-it-yourself communities.

When I finally came across A People’s History of the United States, that first chapter, “Columbus, the Indians and Human Progress” had such a profound impact on how I saw myself in the world. I felt this gravity shift of being liberated from years of feeling embarrassed, invisible, living in the shell of a history whose maintenance only seemed to served those in power, with something to lose; and not us with something to gain — dignity and presence. Zinn had given space to people and voices that no one else had in my education — and that was really inspiring; instead of minimizing Indigenous peoples’ lives and desires, he amplified them. Reading A People’s History, I felt like all the sudden, a filter had been taken off the camera and the world became brighter, crisper, and more immediate.

That disparity between knowing what I knew and lived and what was being taught, and then wanting to find a voice, led me to study stories of struggle and resistance as an undergrad. I then spent twenty years at nonprofit organizations that amplify the voices, the communities, and the histories that are hidden, missing, marginalized, and silenced — be it in the mass media, curriculum, or history books. Most recently, I was one of the founding members of the Zinn Education Project.

With the surge of digital research projects in the last decade, I wanted to be part of that field. So four years ago, I got a Masters of Library and Information Science degree specializing in archives and digital curation. This allows me to dig deeper into historical records and bring these stories to light through digital methods while attending to the humanity and dignity within these records — which is what I do as the digital scholarship librarian with the Center for Black Digital Research.

Hagopian: What incredible work. I’ve got another question for you in your deep dive into the archives. What are a couple of your favorite pieces that you’ve come across?

Cooper: This past July, I got to spend a week going through the letters in the Zinn Archives at Tamiment Library, and the warmth and appreciation that comes through in those letters written to Zinn was touching, and it was familiar. These people felt seen, too; Zinn had acknowledged their experience with COMPASSION!

I also love how his warmth, humor, and compassion draws in people who run across SO MANY segments of the population, and how he was a connector of people; he connected people to have the opportunities to tell their stories with those who could amplify them.

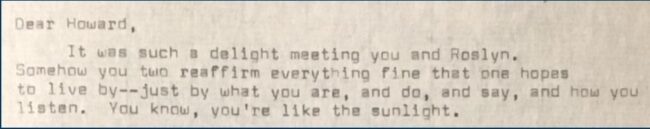

So for instance, here’s a letter from Patricia Marx at WNYC radio in which she comments on Howard Zinn’s wife Roslyn’s warmth. In the first paragraph (below) she says, “It was such a delight meeting you and Roslyn. Somehow you two reaffirm everything fine that one hopes to live by — just by what you are, and do, and say, and how you listen. You know, you’re like the sunlight.”

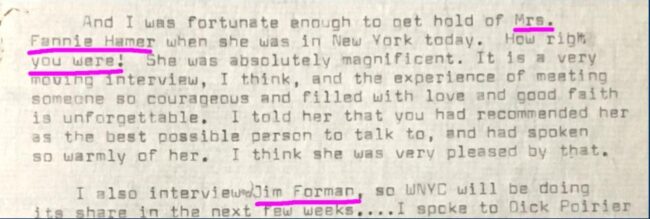

She goes on to thank Zinn for suggesting Fannie Lou Hamer and Jim Forman to be interviewed. She writes:

[Transcript: And I was fortunate enough to get hold of Mrs. Fannie Hamer . . . How right you were! She was absolutely magnificent. It is a very moving interview, I think, and the experience of meeting someone so courageous and filled with love and good faith is unforgettable. I told her that you had recommended her as the best possible person to talk to, and had spoken so warmly of her. I think that she was very pleased by that.]

The other thing I love is seeing some of the foreshadows to writing A People’s History.

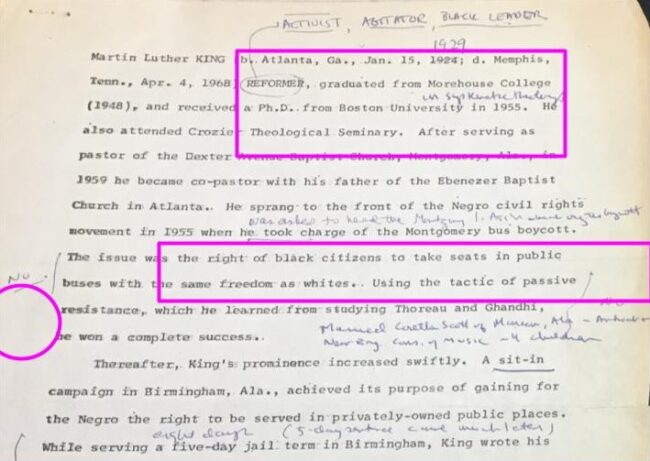

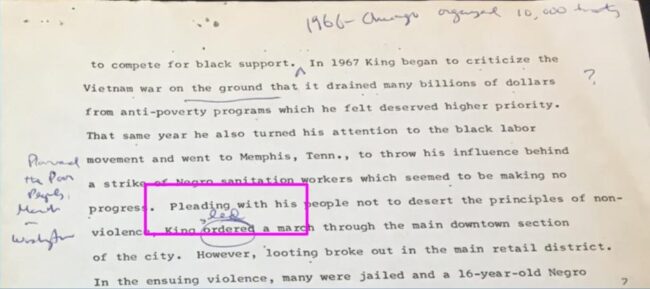

In 1973, Zinn was asked by historian John Garrity to write a 700-word biography of Martin Luther King Jr. for an encyclopedia. Zinn was given a draft sketch — seen below.

On the excerpt below, you see how he is revising it and places King within a movement, and describing his leadership with a sense of action.

In this first example, Zinn first corrects King’s birth year from 1924 to 1929.

Instead of describing King as a “reformer,” Zinn jots down active descriptors — Activist, Agitator, Black Leader.

He edits the passage that King “took charge” of the Montgomery Bus Boycott to “he was asked to lead the Montgomery Bus Boycott by the association who had organized the boycott.”

Then there’s just a firm NO written next to the supposed reason for the boycott; it wasn’t just the issue “of Black citizens to take seats in public buses with the same freedom as whites.”

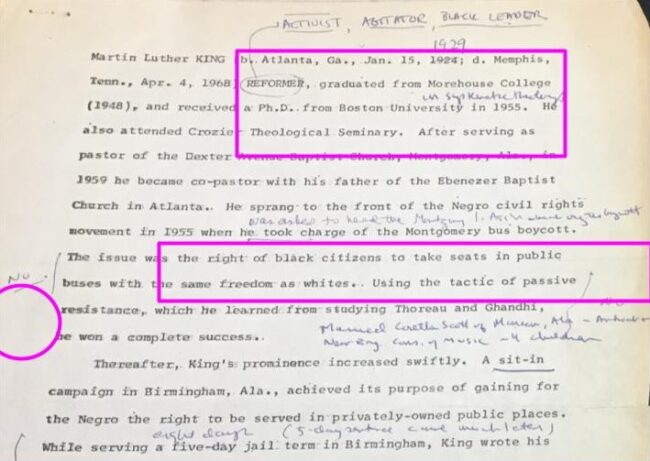

Then finally, in the excerpt below, the shift of language in “King ordered a march” to “King led a march” — just a different sensibility and places King in a movement of people.

It’s great to see how easy, and how impactful it can be to write with compassion, centering the humanity of people, and framing them as part of larger, organized resistance.

Hagopian: Thank you, Lauren. That’s really beautiful. It’s incredible to pull back the curtain and see how Howard developed his method and techniques that he would use later on. Thank you for sharing that with us.

Zirin: You’re also extremely quotable, Lauren. I want to remember those words, put them on paper. That was fantastic.

Hagopian: Yeah, thank you so much for that.

Anthony Arnove on Voices of a People’s History

Hagopian: Howard was committed not only to writing about the people who were left out of most textbooks, but to making sure we learn history from their own words, his books, and with public readings by professional actors and musicians.

So, we’ll talk with Anthony Arnove about the project that is keeping that going most importantly with high school students. Anthony has a long history of collaborating with Howard, including co-editing Voices of a People’s History, which was a staple in my classroom, and writing an introduction for the latest edition of A People’s History of the United States. Anthony, welcome, good to have you here.

Anthony Arnove Transcript

Anthony Arnove: It’s really good to be here. Thank you, Jesse. Thank you, Dave. It’s really a special day. It’s just beautiful to see all the statements. It was twenty years ago that the project that became Voices of a People’s History of the United States started, in a bar in Brooklyn, an event that Howard and I did at a Community Church there. One of the things that Howard really thought was part of the power of A People’s History of the United States was not so much his analysis and synthesis, as important as that was, but that readers discovered in the book voices that had been excluded from their traditional textbooks and education, from the culture, and they were so moved to encounter many of them — Eugene Debs, Frederick Douglass, Helen Keller, maybe even people like King — who we’ve been taught and been shown in one light, in a very different light. Maybe he understood those words, the words that inspired him to write A People’s History, the words that emerge from people’s movements, from social movements in history. That was kind of part of his work.

So, this very interesting thing happened after we started working on this book to gather those primary sources. Harper Collins had sold a million copies of A People’s History. It’s now nearly at four million copies, and of course, many more when you consider the used copies and the library copies and so on. But a million copies had sold, and they [Harper Collins] wanted to organize a conference of historians. And Howard said very simply, “No.” He had a different idea, and that was to bring together actors and musicians and writers to highlight and share the words of people who had spoken out against injustice from our past, and to hear how they speak to the present. He said we are going to produce our very first performance in New York City. Then we’re coming here for the twentieth anniversary of that event, and there was something so powerful about hearing those words and hearing them in a collective setting. At this one-time event we realized there was something incredibly important in this form. There was so much importance in all of the theater of music, other forms of cultural expression, and to see the actors, like Danny Glover and Marisa Tomei and James Earl Jones, and musicians like Patti Smith, and writers like Kurt Vonnegut.

These words are galvanizing and inspiring, and it’s led to many years now of performances around the country, and internationally in Ireland and the UK, Australia, and elsewhere. But then also finding ways to bring these original sources, these documents into schools, and to work with students to understand these texts. Also themselves to take ownership over them and perform them, and bring them to life, and find their own voices through that process. So it’s really exciting twenty years on to be able to continue that work and to see all of the artists and all the students who draw inspiration from Howard’s work.

Hagopian: No doubt. Thank you so much for sharing that, Anthony. Some of the best nights of my life have been at the Voices of a People’s History shows. So really, thank you, for helping to organize those events.

Kidada E. Williams

Hagopian: In addition to talking about Howard Zinn this evening, we also want to highlight the historians who preceded him and the countless historians who are expanding the field today.

Some people incorrectly refer to Howard Zinn as the first or only people’s historian. But we want to show you some examples of historians who preceded Zinn, many women among them. As Pero Dagbovie says: “Historians without portfolio.”

We are pleased to be joined by one of the most innovative contemporary people’s historians who draws on the work of those earlier historians and brings people’s history to the public with podcasts.

I’m happy to introduce Dr. Kidada E. Williams, author of the They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I and the upcoming book I Saw Death Coming: A History of Terror and Survival in the War Against Reconstruction. She is also the producer and host of one of my favorite podcasts, Seizing Freedom. Welcome, Dr. Williams! So glad to be with you again.

Kidada E. Williams Transcript

Kidada E. Williams: Thank you so much for having me. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Hagopian: Your work and the upcoming book, I Saw Death Coming, gives evidence to the thread of white supremacist violence throughout U.S. history. So I want to know more from you about what we can learn from people who have resisted in the past and about how teachers should resist the repressive laws and threats today to teaching truth.

Williams: I think that’s an excellent question. I think one of the things that we can learn is that there is power in saying that people’s lives, freedoms, and futures matter, and that those declarations inspired people across the generations to collective action. And they still have that power to inspire people to build a more just world today. And so I think there are some interconnected lessons that we can learn from our predecessors, and this is something I think that teachers can take in mind. One is that fighting for freedom and justice is best done collectively. I think that that sort of fits the Zinn Education Project so well. Teachers can fight and win by working with other educators, with librarians, with students and activists. Primarily, I think by accessing the historical records. I think we have to understand what the laws say and we have to be strategic as we fight them. And so sometimes it means sort of considering: Do the laws prohibit us from teaching historical records cataloged by the Library of Congress, by the National Archives, by state archives?

These institutions, along with the Zinn Education Project, are our partners in the struggle, and they provide records and lessons that let the students see the records for themselves. But I think we also fight these unjust laws by reaching out to lawmakers, by running for office, and by direct action protests.

Zirin:Dr. Williams, hello, I’m Dave Zirin. I’m a big fan, first time talking to you. I was curious in what ways your work has been influenced by Howard Zinn, and perhaps you could name a couple of other historians who have informed your scholarship.

Williams: What Howard Zinn taught me is that whether it’s war, incarceration or censorship, we have to believe. If we say we believe in a just world, than we have a duty to disturb injustice and unjust practices wherever they are. We can’t give proponents of unjust practices and policies and their asylum enablers a moment of peace. So, we have to call unjust policies and practices by their names, and we have to use our voices, even if they shake while we do it. He also taught me that my experiences, my understanding of the world, particularly the repression of African Americans, doesn’t happen in a vacuum, and that practical struggles are connected to other people’s struggles.

In terms of other historians, as a historian I’m going to go back to, I think, some of the earlier historians. Some of the earlier truth tellers and history fighters. And so for me, the ones who inspired me, I think, to give a quick list. Frederick Douglass for not letting Confederates or Unionists off the hook. He didn’t let either one off the hook. T. Thomas Fortune, who understood the need for a very spirited coalition of activists to fight rising oppression of working and poor people even before Jim Crow was fully installed. So T. Thomas Fortune is there before a lot of the other activists we’re more familiar with. Ida B. Wells-Barnett, of course, for telling the truth about lynching and race. William Monroe Trotter for fighting for working class people. And then W. E. B. Du Bois. And Wanda Rosen for helping more Black people see the global nature of the fight. I think they inspired me because they didn’t all live to enjoy the freedoms they fought for. But they said that Black people’s lives, freedoms and futures mattered, and they helped us understand that a better world was possible.

Hagopian: No doubt. I love that, and I just wanted to wrap up with the question: Why do you take the approach you do to sharing people’s history, and whose voices are you most interested in amplifying? And why? I asked this because there’s some just incredible voices that you share on your podcast. I’m thinking of Harry Jarvis, who had run away from a Virginia plantation on which he was enslaved. And you had an actor reading his words, and I thought maybe we could just play this before you answer.

I went to him and asked him to let me enlist, but he said it wasn’t a Black man’s war. I told him it would be a Black man’s war before they got through.

Williams: Thanks for playing that clip. It’s one of my favorites. As we got the show together, it was one of the things that I knew I absolutely had to have. He’s playing a role or playing in this larger African-American radical stand against slavery. And it’s stories like this that are often the ones that really register, and their proponents ignore when they tell the history, and so I am most intent on amplifying voices like his, because I think they matter for understanding what happened. You can understand what really happened in the context of this war, particularly with Emancipation. As a result, if you understood that people like Harry Jarvis understood something about the nation and about the war and about Black people’s commitment to freedom, that obviously Lincoln and the rest of the Unionists and Confederates did. It’s those kinds of stories, those unexpected stories of often marginalized people who play a role in turning the course of history, that I think are important for understanding what really happened, and its impact today.

Hagopian: Absolutely brilliant.

Zirin: Thank you so much. Thank you.

Williams: Thank you. Right on.

People’s Historian Classes and Young People’s History Books

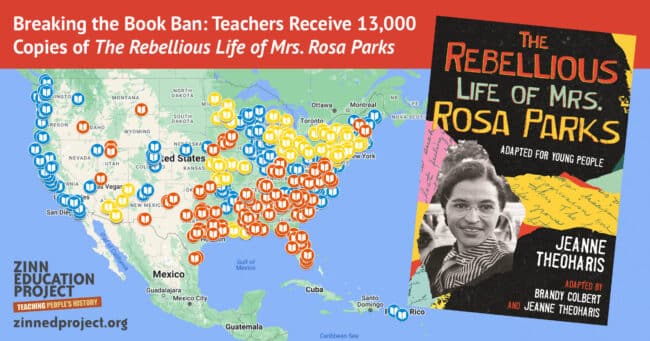

Hagopian: I enjoyed that conversation. It’s the kind of conversation that we have on a monthly basis with the people’s historian online classes that we hold once a month, and I want to encourage you all to check out those sessions. We’ve had Dave Zirin on there. We’ve had Dr. Kidada Williams on there, and you can sign up for the new sessions that are coming up this school year. The people’s history online classes, Teach the Black Freedom Struggle, was really launched by historian Jeanne Theoharis, who conceived of this series at the beginning of the pandemic and has helped curate it ever since. She is the author of a young adult book about Rosa Parks, as well as the original edition, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks.

Thanks to a donation, we’ve sent 13,000 copies of the YA version of that book to teachers all over the U.S. You’ll see the on map where we have sent the book. The red indicates locations with laws against teaching honestly about racism in U.S. history.

So we can only imagine that many thousands of teachers in those states are breaking the law by teaching the truth about Rosa Parks and her lifelong commitment to the Black Freedom Struggle. So thank you so much, Jeanne Theoharis, for all you have provided for educators across the country and for helping to launch this important resource for educators.

I really want to encourage people to get their hands on some of these people’s history books. You see some on the screen right there. A Young People’s History of the United States, Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop. Some incredible titles. Ah, Dave also has a YA version of a book he did with Michael Bennett, Things That Make White People Uncomfortable. So I highly recommend educators get their hands on those books.

Howard Zinn’s Humor

Zirin: Awesome. Well, now I’m going to just say a couple of things before showing a clip. It’s a clip from Howard Zinn on where to find a Communist, and I think it’s hilarious. And one of the reasons why we want to show it is, I gotta tell you when you talk to people who were students of Howard or saw him speak, one of the first things that they say in my experience is, he was really funny. I mean, he was a funny person.

Humor came very naturally to Howard, and it was a terrific kind of humor. It wasn’t, “Who here is from out of town?” No, it wasn’t like that! It was really wielding humor as a way to disarm people, as a way to have them listen to what he was going to say next, because it might be another joke at the expense, always, of the powerful. And it was something that he was able to use to really, I think, capture the attention of an audience, and, like I said, it came very easily to Howard. But it was also very intentional, and I think this clip shows that quite clearly.

Zinn Transcript

Zinn (video): In the year 1948, a series of pamphlets were distributed by the House Committee on American Activities entitled The One Hundred Things You Should Know About Communism. I came across this in my files. I keep files on them. It’s only fair.

I was impressed by the thought that the committee knew a hundred things about Communism, that the pamphlets had one hundred questions and answers. Question one, What is Communism? So the idea is to start with something easy. It requires a brief answer, a system by which one small group seeks to rule the world. The answer was probably drawn up by the people who later founded the Trilateral Commission.

Can I just skip to question seventy six? Where can the Communist be found in everyday life? This question, particularly because there have been times when I was in need of a Communist and didn’t know where to find one. Answer: find him in your school, in your church, or your civic club.

Question eighty-six: Is the YMCA a Communist target? This is really important. No wonder they put so much chlorine in the pool. Yes, so is the YWCA.

Zirin: But one thing I’ll say, Jesse, before you come in, one of the my favorite parts of that clip is the sort of buzz in the audience when Howard starts speaking. That’s what I’m talking about, using humor with intentionality. People wanted to hear what he was going to say next precisely because they knew he was going to take on this really horrific instrument of oppression and not just lampoon it, but slice it, dice it, and by the time it’s done, they seem not so powerful and scary, but actually people that we can confront and even defeat. That’s the power of Howard Zinn’s humor.

Martín Espada

And I’m happy now to get to introduce poet, translator, editor, and attorney, Martín Espada. So glad to have you with us. Author of numerous poetry collections, including Floaters and Zapata’s Disciple. Welcome, and thanks for being with us this evening.

Martín Espada Transcript

Martín Espada: Thank you very much, Jesse. And happy birthday, Howard.

Hagopian: Absolutely. I’ll jump right into it. You wrote two poems about Howard Zinn after he died. So can you please share “Castles for the Laborers and Ball Games on the Radio”?

Espada: Yes, indeed, I did write two poems. The first I wrote for his memorial service after he died. It didn’t quite say what I wanted it to say. So this is my second attempt.

Castles for the Laborers and Ball Games on the Radio (For Howard Zinn, 1922–2010)

We stood together at the top of his icy steps, without a word for once,

squinting at the hill below and the tumble we were about to take,

heads bumping on every step till our bodies rolled into the street.

He was older than the bread lines of the Great Depression. Before the War

he labored at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, even organized apprentices, but now

there was ice. I outweighed him by a hundred pounds; when my feet began

to skid, I would land on him and hear the crunch of his surgically repaired spine.

The books I held for him would fly away like doves disobeying an amateur magician.

Let’s go back in the house, I said. Show me the baseball Sandy Koufax signed to you:

“from one lefty to another.” Instead, he picked up a blue plastic bucket of sand,

the kind of pail good for building castles at Coney Island, tossed a fist of sand

down onto the sun-frozen concrete and took the first step, delicately. Again

and again, he would throw a handful of sand in the air like bread for pigeons,

then probe with the tip of his shoe for the sandy place on the next step:

sand, then step; sand, then step. Every time he took a step I took a step,

an apprentice shadow studying the movements of his teacher, the body.

This is how I came to dance a soft-shoe in size fourteen boots, grinding

my toes into the gritty spots he left behind on the ice. I was there:

I saw him turn the tundra into the beach with a wave of his hand,

Coney Island of castles for the laborers and ballgames on the radio,

showing the way across the ice and down the hill into the street,

where he spoke to me the last words of the last lesson: You drive.

Zirin: Wow, Mr. Espada, that poem gives terrific insights into your relationship with Howard. I was wondering if you could please share more about that relationship and perhaps tell us about his interest in poetry.

Espada: Well, Howard and I were close friends. It felt as if I always knew him. My father was actually friends with Howard’s brother, Shelley. Then they were organizers together in Brooklyn, in the 1960s. Howard was a great teacher. He was one of my great teachers, despite the fact that I never took a single class with him.

He was, as you pointed out, Dave, a few minutes ago, a very funny guy, and his humor comes across in that poem, especially the punchline at the end. We were acting out metaphors. Sometimes people do that. We were acting out metaphors, and all this really happened, by the way. We were on our way to speak together at a rally in Cambridge against the bombing of Gaza, and I remember it very well. It’s the last day I spent with Howard. His interest in poetry was remarkable. He was interested in everything.

First of all, I should say that Howard had the soul of a poet. He had the craft of a poet. I’m not speaking as a writer as much as a performer. Now you were talking about performance. I used to love to watch Howard backstage in the wings, so I could see him behind the podium as he moved his hands while he spoke. You may have noticed Howard doing that in a clip. You may have noticed me doing that just now. It’s not a coincidence. But as far as poetry is concerned, of the radical tradition in particular, Howard was, if you pardon the pun, very well versed.

There was an obscure article he published, called Rise Like Lions: The Role of Artists in a Time of War, and there he quoted poets ranging from Edna St. Vincent Millet to Percy Bysshe Shelley and The Mask of Anarchy. That was, I think, his favorite single poem. “Rise like lions after a slumber in unvanquishable number.” Well, that was Howard.

Hagopian: I love that description. Thank you for sharing that in your book, Zapata’s Disciple. It was on the list of titles banned in Tucson in 2012, as part of the attack on the Mexican American studies program outlawed by the state of Arizona. In the introduction to a new addition you refer to a bomb threat you received at a reading in Tucson. Then you said this quote in the end: “This is just another bomb threat. All they have done is force us to evacuate the building. We will gather ourselves in the dark, and keep reading to each other in whatever light we can find.” So what would you say about the increased numbers of cities and states banning books today?

Hagopian: I love that description. Thank you for sharing that in your book, Zapata’s Disciple. It was on the list of titles banned in Tucson in 2012, as part of the attack on the Mexican American studies program outlawed by the state of Arizona. In the introduction to a new addition you refer to a bomb threat you received at a reading in Tucson. Then you said this quote in the end: “This is just another bomb threat. All they have done is force us to evacuate the building. We will gather ourselves in the dark, and keep reading to each other in whatever light we can find.” So what would you say about the increased numbers of cities and states banning books today?

Espada: I would say that we must be ever vigilant because censorship works. I can say that from personal experience. Books are like people. A book has a lifespan. Books die, too, and for every book like Howard’s A People’s History, with four million copies sold and counting, a book that has transcended every attempt to censor, there are hundreds that die. So we have to shake ourselves from the complacency we sometimes feel in this country when it comes to issues of censorship and book banning. The notion of our freedoms is something that sometimes causes us to put down our weapons. We must pick up our weapons to battle against censorship. It is real. It is happening now, and the sad fact is, most of the time we will not know when books have been censored.

The only difference between this historical moment and most historical moments when it comes to censorship is the brazenness of it. People are being very open about censorship to the point where they are now passing laws that legislate censorship. We don’t have the privilege of knowing what has been banned. We have to find out the hard way. That’s how I found out my book had been banned, and my book died. Zapata’s Disciple died. It went out of print. If it wasn’t for the fact that it was ultimately to be printed in a new edition from Northeastern University Press, nobody would be able to read it today.

Hagopian: Thank you.

Imani Perry

Zirin: I thank you so much for joining us. That was incredibly moving, and it rang incredibly true. What a line up that we have here! Please welcome Imani Perry in the house! I’m so excited. Yes, I am thrilled to introduce Imani Perry, professor of African-American Studies at Princeton University and author of numerous books, including Looking for Lorraine, which I have read and have recommended to everybody, and South to America. Imani Perry, thank you so much for joining us.

Imani Perry Transcript

Imani Perry: Oh, thank you for having me. I’m delighted.

Zirin: All right. So you’ve got this new book South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation, and you reference books that you recommend in that incredible text, including a book that maybe a lot of people don’t know that Howard Zinn wrote called The Southern Mystique. Now, with so many books that have been written about the South, why is Southern Mystique on your short list?

Perry: Well, I mean he does in many ways what I aspire to do, which is to get past the mythology and actually understand the centrality of the South and the American project, and also to sort of evade the danger. And this is 1964 when this book comes out, which is really important, because there’s a sense in that moment, and it continues that the South is this outlier in terms of the depth of American racism, and towards the depths of exploitation. And he’s saying then that the differences between the regions are maybe of a degree, but not substance in that book. And it’s this incredible example also of the uses of history. He was clear about the uses of history, right? We tell history in order to get us closer to something like freedom and also as a marvelous example of the use of experience.

So, his experience being in the South as an observer, but also a deep participant in the movement, and also someone who was part of a Black institution in the South, and seeing through that lens actually, I think you know, allows for him to tell a story. Just to sort of go back to the point that it’s 1964, really. Briefly, this is the year of Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney being murdered. This is the year of the Harlem riots, right. And so in that moment to be saying, “No, this isn’t just a Southern story. There’s something particular happening here that we all can learn from.” But this is a story of what this nation’s project has been that has to be addressed directly.

Zirin: And before you go in, Jesse, just pointing out that Howard, along with many of the activists at the time, was at the funeral of Schwerner, Goodman, and Chaney. Not exactly an undangerous thing to do to travel to Neshoba County to commemorate those three. Back to you, Jesse.

Hagopian: I didn’t know that. Really cool. Well, it’s great to be with you. You know, I’ve really gained so much from your work. Your book on hip-hop has been important to me for a long time, and so I’m just really glad you could join us this evening. I was wondering about another panel that you were on. You were on a panel with Howard Zinn in 1997, and I was wondering if you could tell us more about that experience.

Perry: So here we go, learning from history, right? It was a remarkable experience. It was a joint keynote. Part of what made it remarkable is that he went first, which I thought was this really sort of [unexpected]. I was young, and I didn’t have a sense of how significant that was, but he let me sort of be the anchor. I was like twenty-four years old. And we saw an example, just a sort of brilliant but also affable and natural disposition, and we talked about how one lives a life as a person of conscience. I just was so moved by the way he made space for me, and I was not his student, but it was absolutely a moment of being a student that I have modeled later.

Did you make space for young people? You make space for them to tell their stories, to exercise their voice. Just the attentiveness that he displayed in that moment was also, to what I was saying, I hate to say this, but it’s rare. A worldwide historian, right? It was extremely influential to just be attentive to this. I’m a graduate student, and I love that that seems to be a thread throughout his life, trying to empower students wherever he was.

Zirin: There’s another book by Howard, which some people maybe aren’t familiar with, the way people might not be familiar with The Southern Mystique, and that’s his book on SNCC, which is called SNCC: The New Abolitionists. I was wondering if you could speak a little about that text. First of all, which to me is an incredible demonstration of what a social history canon should be. Also, I wanted to ask you what you think we can learn from the work of SNCC for the troubled times in which we are in today. I mean, I think it’s such an important text, and it was prescient. So, now there have been a number of scholars who talk about the organizing tradition that you shouldn’t talk about the movement simply in terms of mobilization, or simply in terms of charismatic leadership.

Perry: He’s doing that as the movement is happening, drawing our attention to the young people who are on the ground every day. Understand that it is everyday, ordinary people, and their work that is going to transform the country. That it’s important to attend to what the sharecroppers are doing, what the power of actually just getting people to confront the incredible danger, to register to vote, for example. So, it’s a really important book, an early book, one that I hope more people read.

The significance of SNCC, I think, can’t be overstated. I mean, we talk about the major legislation, the Congressional legislative vote, the Voting Rights Act, the Civil Rights Act. This is the product of the labor of young people who decided to devote their lives to the cause of freedom. When nothing would have given them the indication that they were going to win in this struggle. Twenty-year- old people who are in harm’s way every single day, and I think it’s a testament. I’m really looking forward to hearing Ms. Walker hopefully talk about this because she’s written so beautifully about what it meant for him to be present with young people, to be at the protest with them, and then ultimately to be punished for that. There’s trust there, there’s respect there, again a recognition of their work. When I often mentioned to my students when we talk about SNCC, these are people who were your age. They were trying to figure things out, and they also exceeded the imaginations of their elders. And I think that’s really important, especially today, because we’re in a morass.

Hagopian: Yeah, we need imaginators. Yes, we do. And we desperately need more national student organizations to press back against these anti-history laws and attacks on women. Thank you so much for sharing this evening with us. Imani Perry, really appreciate you.

Perry: Thank you for doing the work.

Zirin: Thank you, Professor. I gotta tell you, Jesse, when I did my book, The Kaepernick Effect, a huge influence was reading SNCC: The New Abolitionists because the approach was. . . I was asked to write a book about Kaepernick, and I was like that sounds boring. Let’s write about the people who are actually affected by the taking of the knee. Let’s talk about high school students, college students, people who actually risked something at a young age. Then I set about talking and interviewing them, and it was completely driven by reading that book, and then thinking about what a Kaepernick book should look like, and not writing it as history from above, but history from below.

Alice Walker

Hagopian: I’m really pleased and honored to introduce Alice Walker, award-winning author of so many books that I can’t begin to name them all. I think everyone needs to know that Alice Walker was a student of Howard Zinn’s at Spelman College. It’s an honor to be with you this evening. Thank you so much for joining this panel. I’m really happy to be with you, really happy to be thinking about Howard Zinn in this way, that he’s still soaring, his spirit is still strong. I can feel it tonight for sure. Then you’ve written beautifully about the importance of teachers in your life, and I was hoping you could speak about that and tell us what professor Zinn was like as a teacher in the classroom.

Alice Walker Transcript

Alice Walker: I met him, really, when I had been honored with some prize or other at Spelman, and there was a little reception, and we were sitting next to each other. Now you have to understand that I had never in my life sat next to a white person, and so it was extremely interesting to have him be very funny, very warm, and very curious about my life. And we became friends because he was so much himself. It was something I had never imagined could happen in that part of Georgia at that time. It’s extraordinary, I mean, you can’t even hardly imagine it now.

And in the classroom, what engaged us all was his humor, and also his knowledge about Russia. Because I had been to the Soviet Union and didn’t speak a word of Russian, and he had a class on Russian literature, which he taught. And I wrote about Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, and he understood. And although there was a criticism among the other teachers that I could not possibly have written this book while doing this essay, he said, “Well, actually, nobody else in Atlanta could have written it.” So we became friends, and I became friends as well with his wife Roslyn and the children. They were fairly small then, but I always related to them as a unit, and I was happy. They were together because being an activist at that time from the North was not that safe.

Zirin: Well, I’m glad you ended on that point, Ms. Walker, because we asked you about Zinn in the classroom. But I was wondering if you could speak about the Howard Zinn you knew as an organizer in the movement and a supporter of student struggle.

Walker: Well, the main thing was just that he was always there. I mean he was not directing from the rear. He was not directing from the classroom. He was actually on the street. And it was encouraging. The other teachers were not about to be out there for the most part. And I was a scholarship student, so I was afraid that if I were arrested, I would be turned out of the school. But just having his support, and knowing that there was someone who could see the world the way that we saw it. I mean, a lot of the bourgeois teachers at the school really didn’t quite see the world for the way some of us saw it who were poor. We were poor, we were children of sharecroppers. Often, we were people who knew that we had to have a future, and we had to make it for ourselves. So his staunch understanding of that, coming from the working class himself, was really wonderful.

Zirin: I love that.

Hagopian: I love that. It’s an inspiration as a teacher myself to be there when my students are protesting. Thank you for sharing that, and please, if you can also share some of the connections between the themes you have written about throughout your life, in the soul-stirring literature you have given the world and the histories of disempowered people finding their strength that Howard brings to life.

Walker: It helps to have a teacher who is teaching Russian literature so that early on you have a sense of the stratus, the way that the society all over the world treats the people the lowest down. It helped to have someone who had that understanding on a global level, so that when I started to write my novels about sharecroppers, I could draw on the fact that Howard understood what I was doing,

Zirin: Ms. Walker, if someone asked you, “Could you please talk to us about the Howard Zinn that you knew,” what would be the first story or first image or first memory that would come to your mind?

Walker: Making a joke. I remember once we went to a very middle-class, upper-class college with white girls in Atlanta. And I think my roommate was from Uganda. So we were the only two Black women, and Howard went with us because he was going to make a speech to these women. They were very proper, very staid, very just, you know the gloves and all of that. And he got up to make this speech, and the first thing he said was, “Well, I stand to the left of Mao Tse Tung.” It was hilarious! But, on the other hand, I don’t know if those girls knew who that was, and we all have a different view of Mao now. He was extremely radical, not easily phased. And I think some of that comes from his experiences during the war. I mean, that’s an incredible school. When you find yourself in a war that’s not of your choosing and forced to do things that you don’t agree with, even if you learn about what really happened later. So he was very seasoned. He was very seasoned, and he was at peace with himself as long, I think, as he was actively combating the disaster of the leadership that had caused so much suffering in the world.

Hagopian: Maybe we could just end on a final question. I would love to know your thoughts about the efforts to try to ban Howard Zinn’s work and ban discussions in the classroom about structural racism.

Walker: I’ve been banned for years. I’ve been tempted with some of my novels to just put a little notice in the front, just to warn people that they don’t have to ban it. They can just ignore it. It’s just something you get used to. But we can always hold Howard Zinn up. This is what this program is doing. We can be the people who cherish and love and continue the work that he started. Because you can’t really control the forces. I mean, you can fight them, and you can win sometimes years later. But in the meantime, you do what you’re doing. You continue to celebrate this incredible being. Somehow all of us would feel this incredible being come into our lives and open the door to so much beauty, so much rebellion. I’m not sure I knew that I was such a rebel until we met, and I saw him take on the administration at the school that I was in, which was really a very kind of backward, reactionary glee.

Zirin: So that’s what you’re doing. What you’re doing is what has to be done, and I thank you very deeply. One last very quick question: Is struggle the secret of joy?

Walker: Well, in the novel that you’re referring to, actually, it’s resistance.

Zirin: I’m, sorry. Yes.

Walker: Struggle is great, but absolutely you have to resist. If you don’t resist, I really think you lose a part of your own life. We’re not meant to succumb to dictatorial, crazy people. We’re not. Yeah, and in whatever way you can resist, resist. Resistance is the secret of joy.

Hagopian: What a precious time this has been! I will really cherish this time together. Thank you for your insights and your time this evening.

Walker: You’re welcome.

Myla Kabat-Zinn

Zirin: Next we’re talking to Myla Kabat-Zinn, who is the author with her husband, Jon Kabat-Zinn, of Everyday Blessings. She is the daughter, of course, of Roz and Howard Zinn and the executor of the Howard Zinn Trust. Hello, Myla!

Kabat-Zinn Transcript

Myla Kabat-Zinn: Hello, Dave!

Zirin: It’s so wonderful to have you here. I’m wondering if we could start just by hearing some of your own memories of growing up in a family that was so deeply involved in social justice?

Kabat-Zinn: It’s lovely to be with you this evening, to celebrate what would have been my father’s 100th birthday.

I’ve been thinking about what might be of interest to all of you. I have my own experience of growing up with my father and of course, my mother. And since my father died twelve years ago, as the Executor of the Howard Zinn Trust, I’ve gotten to know and appreciate my father’s work and life in a way I hadn’t before. Over these years, it’s been a huge privilege to work, even in small ways, with some of the people and organizations involved in this event. It has been enlightening and gratifying and deeply meaningful, and I’ve learned so much from them.

Both my parents grew up poor and working class in Brooklyn, New York. My father went to college on the GI Bill. My mother didn’t go to college till many years later. But she read a great deal and had a keen and discerning eye and was a great editor. My father relied on her to read his work and give him feedback. He had always focused his writing on specific issues and movements, but A People’s History was broader in scope and there were key moments when he benefited from my mother’s encouragement to keep working on it because she understood how important it would be.

We left NYC when I was nine and my brother Jeff was seven. We had been living on the Lower East Side in the Lillian Wald Housing project. I remember it as a wonderfully diverse and friendly community. And then my father got a job teaching at Spelman College in Atlanta. We drove for three days and arrived on campus to a new world. This is how my father describes it in his memoir:

We arrived in Atlanta on a hot and rainy night, and Roz and the children awoke to watch the shimmering wet lights on Ponce de Leon Ave. We were in a different world, a thousand miles from home, a universe removed from the sidewalks of New York. Here was a city thick with foliage, fragrant with magnolias and honeysuckle. The air was sweeter and heavier. The people were blacker and whiter.

And he goes on to describe the difficulty of finding someone who would rent to us when they found out where my father worked. And with his usual empathy and insight, he said:

What for us was an inconvenience was for Black people a daily and never-ending humiliation, and behind that a threat of violence to the point of murder.

After about a year, we moved to an apartment on the Spelman College Campus, in a wing of the Infirmary building. One of my fondest memories as a child was participating in plays put on by the Atlanta University Players. The theatrical director Baldwin Burroughs and musical director, J. Preston Cochrane and the student actors were all so gifted and dedicated. There’s so much I don’t remember from my childhood, but what happened in the process of rehearsing and being part of that warm, creative community was extremely meaningful to me. A highlight was being one of the children in their production of the musical The King and I. At that time, there wasn’t the more widespread consciousness we have now of the many issues in the play related to colonialism. But in Atlanta at that time, it was unusual to have an integrated cast. My mother played the British teacher, Anna, and the King was played by Johnny Popwell, a student at Morehouse. Sometimes so-called “amateur” productions are more compelling than professional ones. That was certainly true of this one.

Zirin: Wow! Nice.

Hagopian: So beautiful! Thank you for sharing that. I had one question for you, too, Myla. You mentioned that as the executor of the Howard Zinn Trust, you have gotten to know your father’s work and life in a way you hadn’t before, so I was wondering if you had some pieces you’d most appreciated or learned from.

Kabat-Zinn: There is so much to explore of my father’s writings, and also in videos of him speaking on both the HowardZinn.org and the ZinnEducationProject.org websites. But for now, I’d like to recommend just a few resources for folks interested in learning more about his life and work.

- I recently re-watched the documentary You Can’t be Neutral on a Moving Train. I was struck by how skillfully and movingly it conveys the arc of my father’s life and his involvement in the major movements of his time.

- There is my father’s book The Southern Mystique, as well as his book about the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee titled SNCC: The New Abolitionists.

- I want to mention Bill Bigelow’s interview with my father recorded a few days before he died, titled “One Long Struggle for Justice.”

- And there are videos of my father testifying at trials on the history of civil disobedience. [Below are two examples.]

Howard Zinn’s Testimony in the Cruise Missile and Missile X Factory Trial

The Camden 28 Retrospective: Zinn Recounts His Testimony

- More generally, I’ve also learned important history that I didn’t know from the postings on the Zinn Education Project’s “This Day in History.”

- Lastly, you can hear my father’s wonderful sense of humor in many of his speeches, which were for the most part, unscripted. They are collected in the book Howard Zinn Speaks.

Hagopian: Thank you for sharing all that.

Kabat-Zinn: It’s really been an honor to be here tonight, with so many teachers, people’s historians, librarians, artists, and, importantly, students who are carrying this work forward and maintaining its integrity and broadening its reach. I just want to say, it’s been really heartwarming to be here tonight.

Hagopian: What an incredible night it has been! Thank you, thanks for helping to make this possible and carrying on this legacy that Howard gave us all. There are just so many tools that he gave us to help build these struggles, and it’s really been an honor to get to help organize this event this evening. Thank you for those words, Myla.

Howard Zinn on Incarceration

Hagopian: We have a couple pieces that we really want people to stick around for, and Dave, I was hoping you could talk more about Howard Zinn’s relationship with prisoners and his thoughts on prison abolition. What would Howard Zinn think of Black Lives Matter and the call to abolish prisons?

Zirin: Howard Zinn, I think, would say that it was tremendous that the call has been picked up, a call that has been in the air for decades, and I think that’s why it’s so important for us to know our history. This was one of the great lessons of Howard Zinn’s that we have to realize that we stand on the shoulders of giants, and we have to realize that what we’re doing today, maybe it’s been done in the past, and maybe there are lessons to learn. Maybe there’s an emboldening process, and I think that Howard Zinn being a prison abolitionist dating back decades is something that we need to consider and think about. Now, where did that come from?

I think when you study Howard Zinn’s political life, it’s fascinating to me that he immersed himself in the Black Freedom Struggle and in the anti-war movement and then the 1970s hit, and both of those movements suffered as we went into that decade. And what does Howard Zinn do? He pivots to letter writing with people behind bars, with attempting to help people when they get out of prison. The people who he corresponded with, and we have a lot of that correspondence fortunately. It’s remarkable, the humanity which Howard attempted to connect with people in the most dire situations, but also his effort to tell their story.

Howard had a column in the Boston Globe in the 1970s, where he would write about prisoners he was corresponding with. I mean, not exactly news you get in the mainstream press normally. I bet there’s a great story about how he got a column in the Boston Globe. Because usually the Boston Globe was just set up to bash Zinn, especially during his anti-war activities. But I’ve always felt like Howard Zinn’s passion for trying to really excavate the humanity of people behind bars, I really do think it relates to the passion with which he also writes in A People’s History of the United States about Eugene Debs, the socialist presidential candidate from the first part of the twentieth century. Someone who I learned about for the first time reading A People’s History.

A great Debs quote I read for the first time in A People’s History is when Debs said years ago:

I recognized my kinship with all living things, and made up my mind that I was not one bit better than the meanest on earth. While there is a lower class, I am in it. While there is a criminal element, I am of it, and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.

That’s a sentiment that Howard lived. It wasn’t just words on a page.

Closing

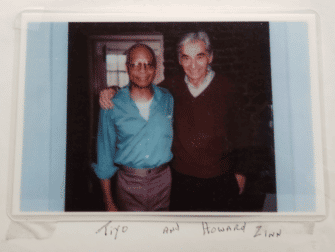

Hagopian: No doubt he lived those words, and for many years, Zinn corresponded with Tiyo Attallah Salah-el. He was a musician, a scholar, and a prison abolitionist, who founded the Coalition for the Abolition of Prisons in 1995, and he was imprisoned for forty years. He died there in Pennsylvania’s Dallas State Correctional Institution in 2018. In 2022, a group of musicians produced an album of his music, including a blues melody for Howards Zinn.

We will listen to this melody in a moment, because I’m going to ask everybody to please make sure you complete the evaluation for this evening. We would love to get your feedback. Please don’t leave without clicking on that link in the chat and giving us some feedback about how this evening went for you. It was truly a magical evening for me, but I’d love to hear your experience of this evening, and as you are filling that out, we will play this song by Tiyo.

Zirin: A big thank you to the ASL interpreters. Sometimes in these meetings, I feel like they are the true heroes. They are not only allowing the words to reach as broad an audience as possible, but they’re also working really hard. So thank you so much.

Hagopian: Thanks, everybody. What a night!

Participant Reflections

Everyone was invited to share reflections on what they learned and the program overall. Here are some of the comments.

Once I push back my tears, I will continue to be inspired not just by Howard Zinn, but by the infinite web of hope we all continue to share. Thanks to all those whose work makes moments like tonight possible. I can breathe deeply again.

The life of Howard Zinn was reflected upon by very special people. I always loved his sense of humor and his way of making points about important issues. He lives on through the people who share his passions.

You filled my soul this evening.

Thank you for an amazing evening filled with so many special remembrances!

OMG! The breadth of his work, the beauty of his words, the phenomenal capacity of his humanity. And a truly amazing roster of speakers and guests.

It was such a wonderful event! Loved all the speakers, their passion and the care with which they spoke. Thank you also for shining the light on Howard Zinn’s work. I have not had the good fortune of meeting him but feel like I know him through his work.

First hand stories, the huge number of materials available, the humor, the way he lived his life.

The fact that Zinn’s daughter learned so much about her father after his death. That means so much to me as I try to navigate being a parent, grandparent, and activist. Joy is central!

The evening inspired me to rededicate myself to the struggles for justice.

A generous evening full of significant “surprises” of the kind Howard especially valued. The program had a warm and inclusive tone and the interpreters helped make inclusion a reality, too.

I felt energized and renewed by Howard Zinn’s belief that teachers can change the world and was inspired by the community of educators and activists who gathered for this event.

After all your programs during COVID — many of them extraordinary — today’s brought us all together in a sacred space. Breathtaking . . . .

Zinn’s life and legacy beyond A People’s History was amazing! Learned so much from every speaker. Awesome to hear so many first hand accounts. Treat to meet every one of the speakers on Zoom.

Wonderful! Thank you! And I also enjoyed conversing with a fellow educator in the breakout session.

You all have made a very thoughtful gathering with a great variety of sharing. I’m so honored to have been able to participate and learn. Thank you.

Thank you for this series and for all the work that you do. My mind has expanded from all that I’ve learned these past six months.

I did not expect it to be interactive. It really worked.

What a great event. Can we do it again on the 110 anniversary?!

Wonderful selection of speakers. Loved the weaving together and the visuals. Wanted more time in breakout room.

You put together a wonderful panel of speakers. Things moved smoothly with the slides. I liked having the breakout session in the middle. It was excellent!

Fabulously welcoming, kind, beautifully conceived and organized.

Hosts and Speakers

Jesse Hagopian is a leadership team member of the Zinn Education Project and a high school teacher. He is also an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, and editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing.

Dave Zirin, The Nation’s sports editor and the author of ten books, including A People’s History of Sports in the United States and The Kaepernick Effect. Zirin is currently writing a biography of Howard Zinn.

Bill Bigelow is curriculum editor of Rethinking Schools magazine and co-director of the Zinn Education Project. He is the author and co-editor of numerous publications, including Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years and A People’s Curriculum for the Earth: Teaching Climate Change and the Environmental Crisis.