On May 13, 1846, the U.S. Congress overwhelmingly voted in favor of President James K. Polk’s request to declare war on Mexico in a dispute over Texas.

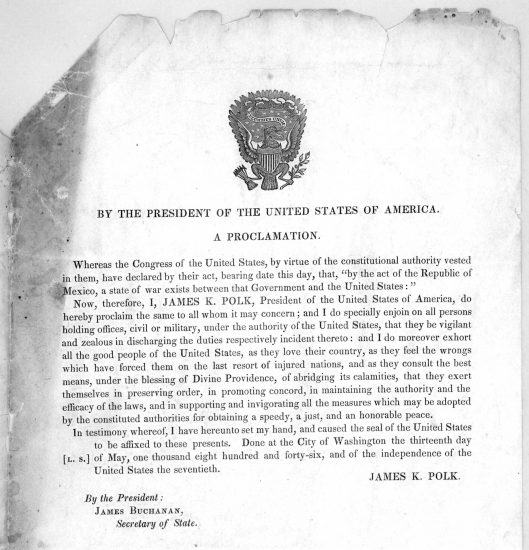

A proclamation by President Polk at the outset of the Mexican-American War. Source: Library of Congress.

Howard Zinn describes the background to the vote in Chapter 8: “We Take Nothing by Conquest, Thank God” of A People’s History of the United States. Read short excerpts below and find a longer excerpt in the free classroom lesson listed under Related Resources.

On May 9, before news of any battles, Polk was suggesting to his cabinet a declaration of war, based on certain money claims against Mexico, and on Mexico’s recent rejection of an American negotiator named John Slidell. Polk recorded in his diary what he said to the cabinet meeting:

I stated . . . that up to this time, as we knew, we had heard of no open act of aggression by the Mexican army, but that the danger was imminent that such acts would be committed. I said that in my opinion we had ample cause of war, and that it was impossible . . . that I could remain silent much longer . . . that the country was excited and impatient on the subject.. . .

The country was not “excited and impatient.” But the President was. When the dispatches arrived from General Taylor telling of casualties from the Mexican attack, Polk summoned the cabinet to hear the news, and they unanimously agreed he should ask for a declaration of war.

. . . Polk spoke of the dispatch of American troops to the Rio Grande as a necessary measure of defense. As John Schroeder says (Mr. Polk’s War): “Indeed, the reverse was true; President Polk had incited war by sending American soldiers into what was disputed territory, historically controlled and inhabited by Mexicans.”

. . . Congress then rushed to approve the war message. Schroeder comments: “The disciplined Democratic majority in the House responded with alacrity and high-handed efficiency to Polk’s May 11 war recommendations.” The bundles of official documents accompanying the war message, supposed to be evidence for Polk’s statement, were not examined, but were tabled immediately by the House. Debate on the bill providing volunteers and money for the war was limited to two hours, and most of this was used up reading selected portions of the tabled documents, so that barely a half-hour was left for discussion of the issues.

. . . A handful of antislavery Congressmen voted against all war measures, seeing the Mexican campaign as a means of extending the southern slave territory. One of these was Joshua Giddings of Ohio, a fiery speaker, physically powerful, who called it “an aggressive, unholy, and unjust war.” He explained his vote against supplying arms and men: “In the murder of Mexicans upon their own soil, or in robbing them of their country, I can take no part either now or hereafter. The guilt of these crimes must rest on others — I will not participate in them. . . .”

Rethinking Schools editor Bill Bigelow explains the importance of teaching outside the textbook about the U.S. Mexico War:

Today’s border with Mexico is the product of invasion and war. Grasping some of the motives for that war and some of its immediate effects begins to provide students the kind of historical context that is crucial for thinking intelligently about the line that separates the United States and Mexico. It also gives students insights into the justifications for and costs of war today.

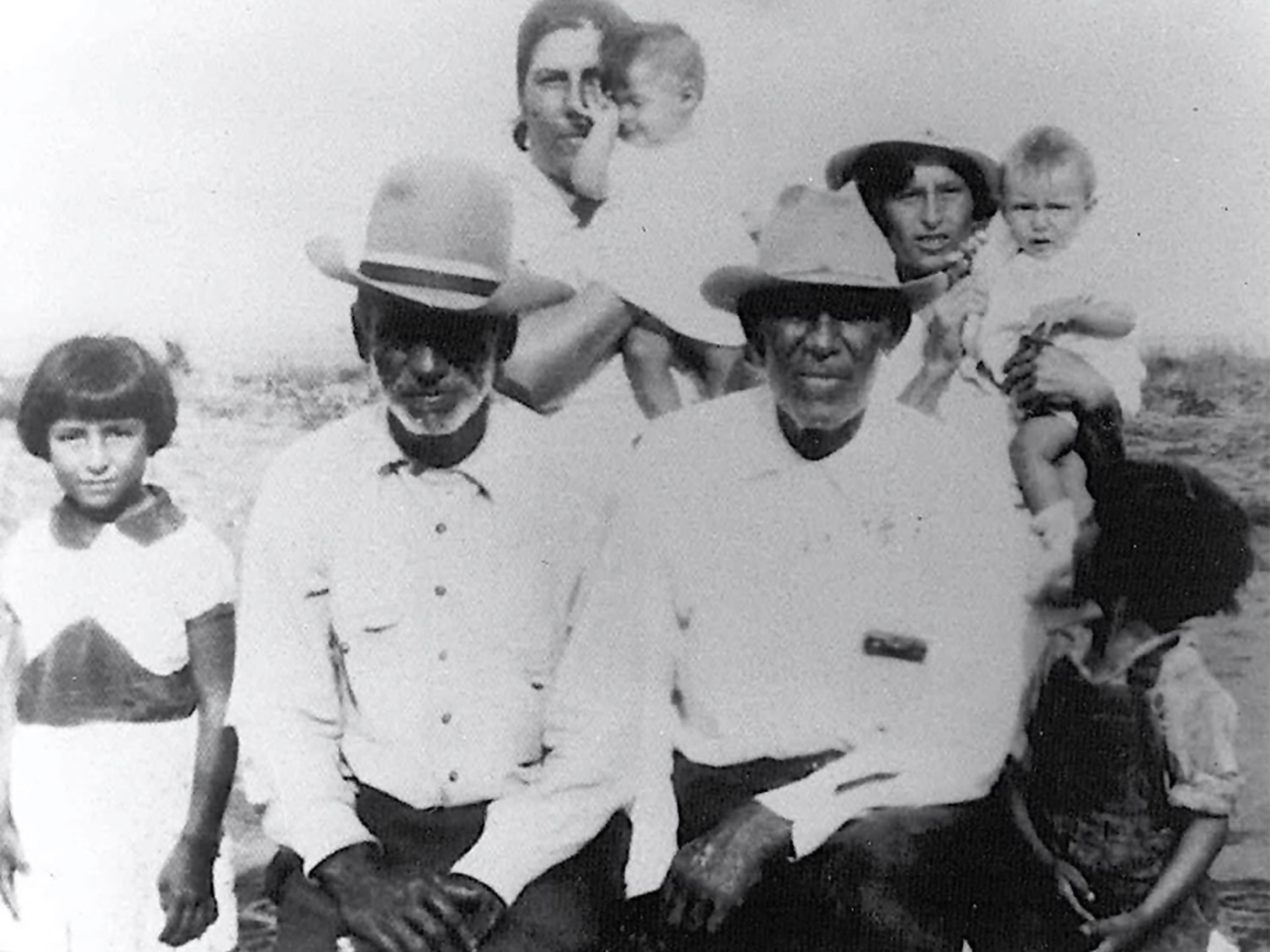

Bigelow is the author of a free downloadable lesson called U.S. Mexico War: “We Take Nothing by Conquest, Thank God.” The lesson features a reading by Howard Zinn and a role play with many voices on the war typically missing from textbooks such as: Cochise, Colonel Ethan Allen Hitchcock, Frederick Douglass, General Mariano Vallejo, Henry David Thoreau, María Josefa Martínez, Padre Antonio José Martínez, the Saint Patrick’s Battalion, and many more. A version of the lesson is also available in Spanish.

Find the lesson and more resources for teaching about the border below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn