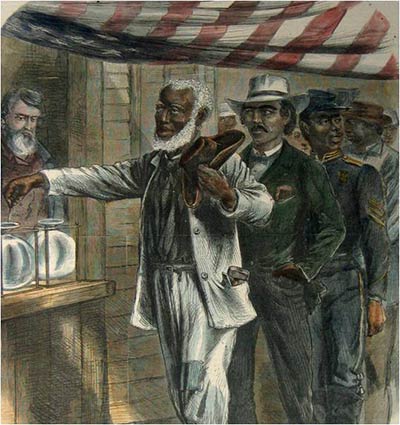

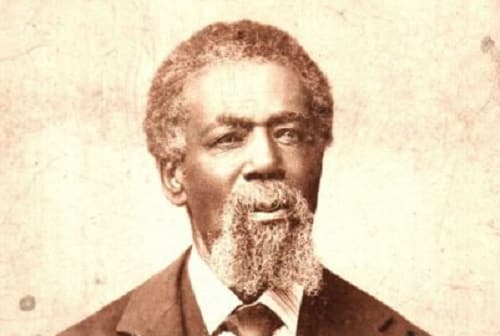

Less than two months after the conclusion of the Civil War and the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, members of the Colored Monitor Union Club convened a mass meeting to assert full citizenship, advance Black unity and seek Congressional action on voting rights for men.

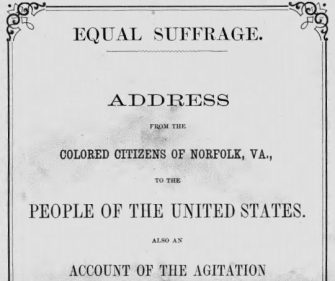

On June 5, 1865, the African American community of Norfolk, Virginia, became the first in the country to seek equal rights on a national level with its Equal Suffrage address “to the People of the United States.”

The Equal Suffrage address laid out its appeal in patriotic terms, starting with the second paragraph:

We do not come before the people of the United States asking an impossibility. We simply ask that a Christian and enlightened people shall, at once, concede to us the full enjoyment of those privileges of full citizenship, which, not only, are our undoubted right, but are indispensable to that elevation and prosperity of our people, which must be the desire of every patriot.

The statement contended that the guarantee of voting rights for African Americans would be the best assurance of Black liberty and equality. “We ask for no expensive aid from military forces, stationed throughout the South” or “overbearing State action,” the address said. “[G]ive us the suffrage, and you may rely upon us to secure justice for ourselves.”

The Norfolk declaration, published later in 1865 as a 30-page pamphlet and distributed across the country, helped build momentum for the 15th Amendment, which was ratified on February 3, 1870, and stated that the “right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

The notion — “give us the suffrage” — would ring throughout the decades as Black citizens sought enforcement of the 15th Amendment, the end of poll taxes and expansion of voting rights laws. A similar version of the “give us the suffrage” refrain echoed in the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “Give Us the Ballot” speech of May 17, 1957, when he proclaimed, “Give us the ballot, and we will no longer have to worry the federal government about our basic rights.”

Norfolk’s Equal Suffrage statement of 1865 encompassed many other African American issues and included references to history. It reminded readers of Black contributions to “national prosperity” as well as to the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and Civil War.

The authors also expressed concern about the post-Civil War activities of defeated Confederates and their sympathizers who “cling to … delusions” about the outcome of the Civil War and were already scheming to deny fair employment and full citizenship to African Americans along with other “treasonable legislation.”

Norfolk’s Black leaders were adamant as they resolved “[t]hat traitors shall not dictate or prescribe to us the terms or conditions of our citizenship, so help us God.”

The address urged fellow African Americans to form labor unions and land associations, the latter for pooling resources to buy large tracts of land with the idea of subdividing it among themselves. It also recommended boycotts against businesses owned by “those who would deny to us our equal rights.”

The demands made by Norfolk’s 1865 Black community reflected a broader movement for full citizenship that included the National Convention of Colored Men in October 1864 in Syracuse, New York. African Americans elsewhere in Virginia soon organized political organizations like Norfolk’s Colored Monitor Union Club. Together, they held a statewide convention on August 2-5, 1865, in Alexandria.

By Michael Knepler, who prepares periodic #tdih posts for the Zinn Education Project.

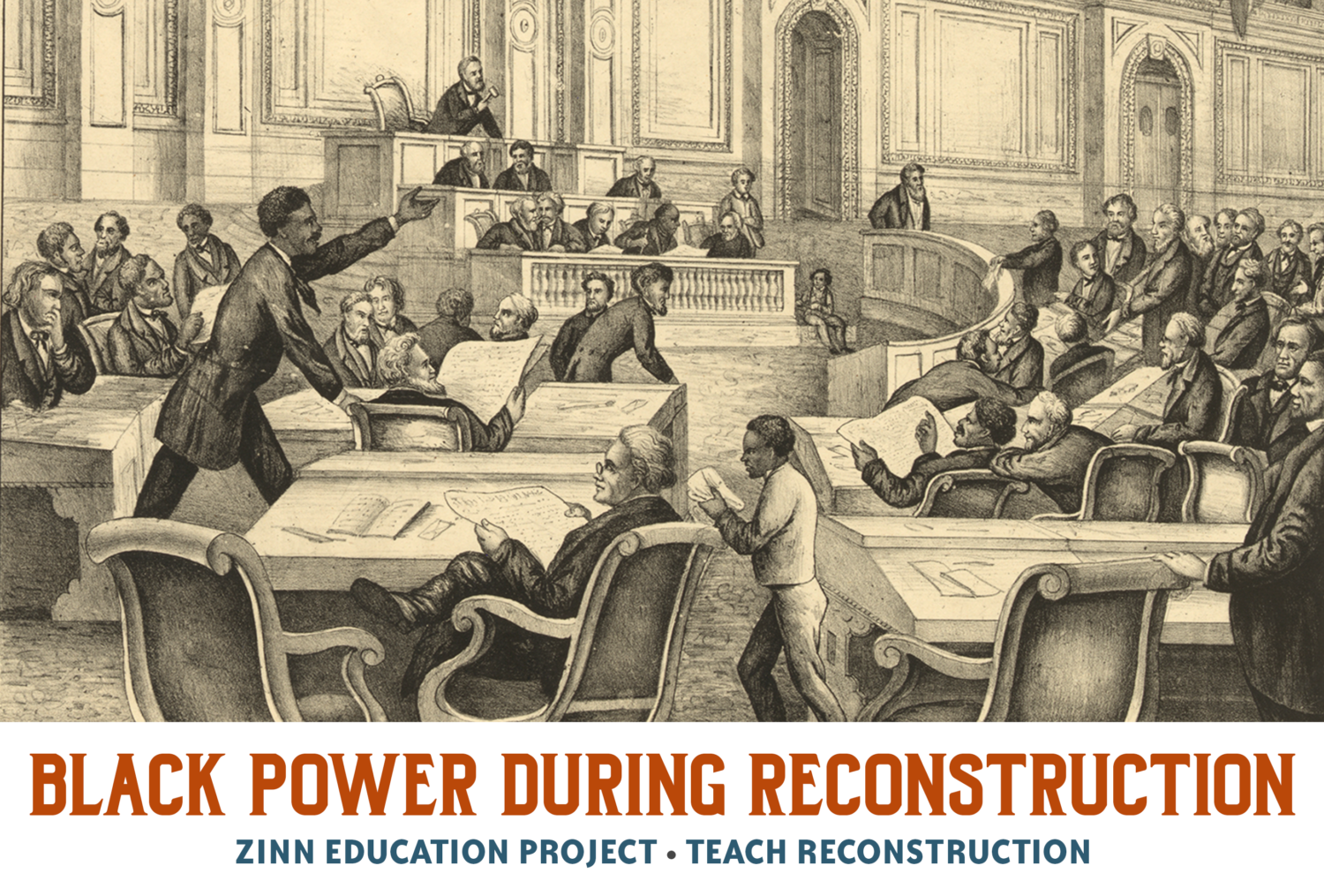

Learn more in the Zinn Education Project national report, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction,” and find teaching resources on Reconstruction below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn