By Ursula Wolfe-Rocca

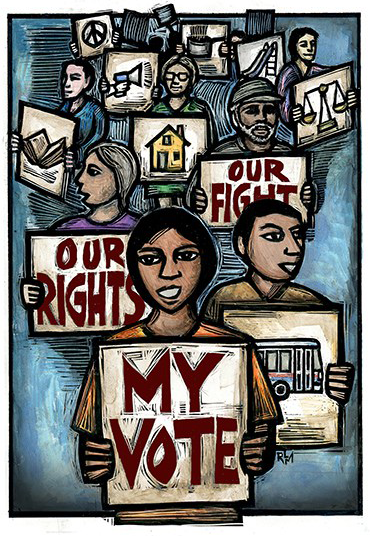

Thousands marched in midtown Manhattan on December 10, 2011, to defend voting rights. By Michael Fleshman.

The struggle for the ballot is emblematic of the struggle to make real the democratic promises of this country’s founding narrative. Just as the United States has never been a true “government by the people, for the people,” the right to vote has always been incomplete, contested, and compromised by the racism, sexism, classism, and xenophobia of policymakers and the interests they act to protect.

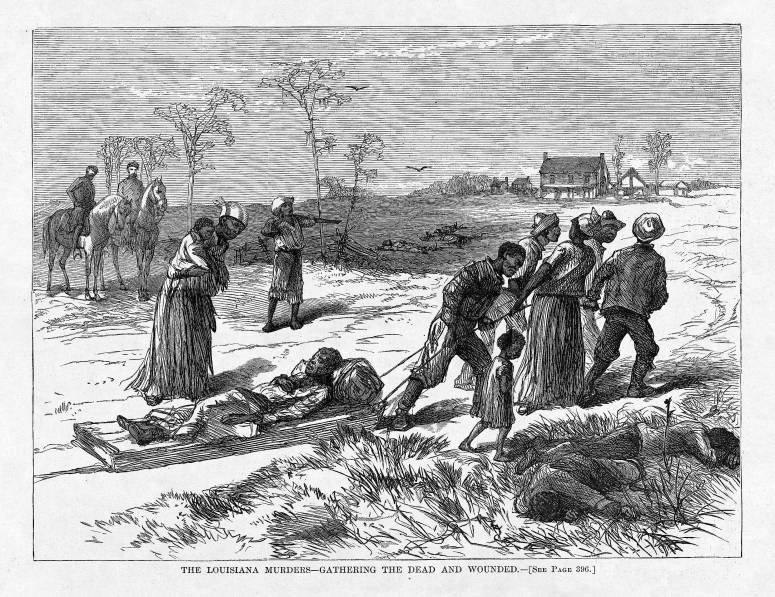

In a moment of renewed and insidious voter suppression, examining the history of voting rights also presents an opportunity to challenge the deeply entrenched fable of the steady forward progress of U.S. history. Voting rights have expanded in the last 400 years, but they have also been taken away, requiring activists to rise up, again and again, to restore the achievements of prior generations. The fight for the ballot is ongoing.

Source: GPA Photo Archive

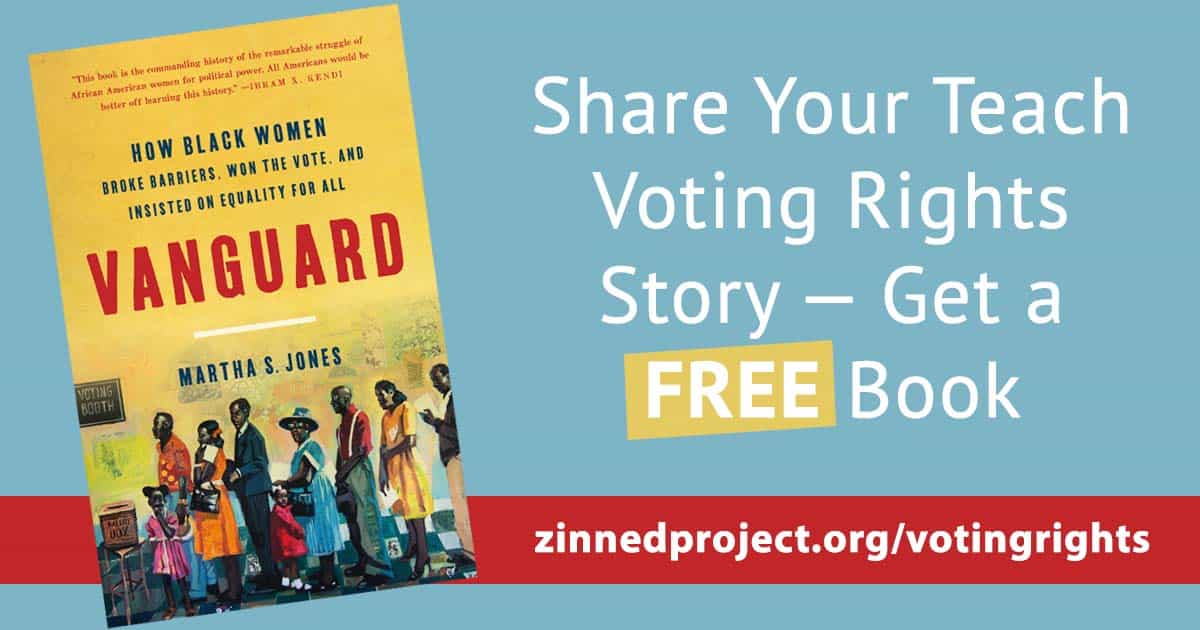

Recent elections have brought forth the old problem of voter suppression in a new guise — voter ID laws, voter roll purges, polling places shuttered. As activists combat these restrictive, antidemocratic measures, it is vital that we provide students historical context for their efforts, which is why the Zinn Education Project has put together a cluster of lessons on the history of voting rights in the United States. These lessons can be taught individually, but they are presented here as a progression.

The first lesson considers the question of who should vote. Students first share their understanding of what makes a “qualified” voter, then reconsider their thinking after a close reading of an oral history by Fannie Lou Hamer.

The second lesson asks students to predict how policymakers might have restricted the right to vote for certain groups to thwart movements and laws that expanded voting rights.

The final lesson is a mixer role play in which students learn about a variety of people with firsthand experience having their voting rights granted or denied. The roles reach back as far as the colonial era and forward to the present. This lesson closes with a timeline activity in which students create a visual map depicting the expansion and contraction of voting rights over time.

SMU Dedman School of Law professor Grant M. Hayden has written:

The history of voting in the United States has not been characterized by a smooth and inexorable progress toward universal political participation. It has instead been much messier, littered with periods of both expansion and retraction of the franchise with respect to many groups of potential voters.

Young people need to know this “messier” history; it is a history that calls us to action, a history that conveys that voting rights are not definitively won, but must be struggled for and defended.

Individual roles for this mixer

- Christia Adair, who went door to door organizing for women’s right to vote in Texas

- Preston Allen, a Native American man living on the Uintah and Ouray Reservation in what is today called Utah

- Marsha Appling-Nunez, who teaches college in Atlanta

- Nathan Bacheldor, who was born to Irish immigrant parents in New York City and fought in the War of 1812

- Ruth Muskrat Bronson, a Cherokee poet, educator, and Indian rights activist who was born in what is today Oklahoma, but was at the time called Indian Territory

- Aracely Calderon, who was born in Guatemala, but is a naturalized U.S. citizen

- Floyd Carrier, an African American Korean War veteran in his 80s

- Xitlaali Castellanos, who learned of the pre-registration option in your Model United Nations club at school

- Maggie Coleman, a 71-year-old African American woman living in rural Georgia

- William T. Combash, a Black lawyer

- Thomas Crawford, a member of the colony’s militia who has been called up to fight in King George’s War

- Frederick Douglass, a prominent abolitionist

- Timothy Duffy, who immigrated to Massachusetts more than 10 years ago, during the Great Famine in Ireland

- Oscar J. Dunn, who was in the 1st Louisiana Native Guard, one of the first all-Black regiments to fight for the Union Army in the Civil War

- Stuart Goldstein, who started the Voting Age Coalition of New Jersey

- Penny Grover, a white, middle-aged artist and a poet, living in New Jersey

- Fannie Lou Hamer, a sharecropper who fought to register Black voters

- Larry Harmon, a white Navy veteran living in Ohio

- Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, a Black woman born free in Maryland who became a prominent antislavery activist

- Gladys Harris, a 66-year-old African American woman who, despite chronic lung disease and a torn ligament in your knee, made her way to the polls to vote on Election Day in 2016

- Joseph Jackson, who cast his ballot in the historic election of Barack Obama from within the confines of a maximum security prison

- Elzie McGill, who worked with the Lowndes County Christian Movement for Human Rights (LCCMHR) to register more Black voters

- Denise McQuade, a 64-year-old white woman who, due to contracting polio when a child, uses a wheelchair

- Lawrence Aaron Nixon, a Black doctor living in Texas

- Peter Williams Ray, a doctor who comes from a free middle-class Black family in New York City

- Modesto Rodriguez, a Mexican American from Pearsall, Texas

- Lamar Smith, a farmer and WWI veteran who was killed working to register Black voters

- Melanie Taylor, who headed to her regular voting site, a church in Charleston, South Carolina, on Election Day in 2018

- Bhagat Singh Thind, who was born in India, but immigrated to the United States in 1913 to study at a U.S. university

- Lee Yok, who came to Oregon in the 1850s from China, before Oregon was even a state

Classroom Stories

I used the first lesson in the unit, Who Gets to Vote? Teaching the Struggle for Voting Rights in the United States, in my United States government course. It fostered great conversation and insight for my students in considering the importance of voting and factors that hinder voting (especially educated voting). My students hadn’t much considered the importance of voting, and some were despairing about the worth of their vote following my lesson on the Electoral College.

Fannie Lou Hamer’s excerpts, especially the second excerpt, revealed to my students something that they hadn’t previously considered: while they didn’t see value in their vote, they hadn’t considered the challenges that have historically and contemporarily prevented citizens from the ability to vote in the first place.

This lesson led my students to reconsider the value of their voice in federal and local elections. I taught it on election day and I believe that it inspired many of them to vote in the election, some of whom left for the polls straight from school! Thank you, as always, for your great resources!

There are so many great elements to the Who Gets to Vote unit. Being a teacher educator, I decided to adapt the first and third lessons for my Master’s in Teaching / Social Studies students. It took about one hour to teach. Teaching virtually over Zoom, here was my procedure:

- Open with them brainstorming on a shared Jamboard “What should be the requirements for voting in the United States?”

- Then, brainstorm some categories of people who have been targeted with voter suppression.

- I broke the class into 3 groups and asked them to brainstorm regulations that would suppress targeted groups of voters.

- The mixer role play was next. I had prepared a condensed list of roles and assigned one to each student.

- Students met in breakout groups to discuss their roles and how any of our new regulations impacted their right to vote.

- Session ended with an open discussion of what they’ve heard on the subject of voter suppression in the 2020 cycle.

My students were deeply engaged throughout the lesson and it generated much discussion. It was interesting for them to consider some of the suppression techniques done by different groups and the extent to which they were based on real-world examples.

As an AP Government teacher, teaching about voting rights is a crucial part of the curriculum, and perhaps one of the more engaging elements of the curriculum as well. During my Political Participation unit, I focus heavily on voting rights and voter participation, particularly because as a Government teacher, registering students to vote and making them understand the role they play in our system is crucial. Having taught in schools with predominately minority student populations, it has been even more crucial for students to understand the ways – historical and today – that voters have been both enfranchised and disenfranchised.

The second lesson in the “Who Gets to Vote?” unit is particularly effective with my students, who draw on their knowledge of US History when they recall ways that Black voters were disenfranchised during Reconstruction and Jim Crow. Expanding on this knowledge to address other groups – low-income individuals, people with disabilities, and college-age students – helps students deepen their thinking of the ways that voting rights have been expanded and restricted.

Our exploration of voting rights ends with a Socratic Seminar on the ways in which voting rights are being expanded and restricted in the current political system, with students focusing on efforts like early voting, voting by mail, voter identification laws, and making Election Day a federal holiday, among other efforts. Students spend a full period discussing the intended and unintended consequences of each of these efforts, and thinking about whether they should be expanded or limited further for the best interests of American voters.

I’m working this summer in one of New York City’s Regional Enrichment Centers (REC), where I teach ELA and Science. We’ve been reading Rita Williams-Garcia’s book, “One Crazy Summer” where the Black Panthers and central to the narrative. In an early chapter, one of the characters notices a Black wall of fame and the 11-year-old was surprised that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wasn’t pictured. She recognized only two of the men, Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali, and none of the women. She did note that a caption under one of the women’s picture’s was “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.” That quote is, of course, from Fannie Lou Hamer.

Thus, I adapted the first lesson in “Who Gets to Vote?” for elementary level students. It went well. I showed two short video clips of Ms. Hamer and the kids had a lively discussion about who should be able to vote; about conditions in the Jim Crow South; and about Fannie Lou Hamer. The next day, we saw the entire 26 minute PBS video on Hamer. We focused on Hamer and her important work for expanding voting rights. For all of my summer students, it was an introduction to a heroine of the Black Freedom Struggle rarely taught in schools. I plan to teach the lesson in my regular classroom when we return.

My Civic students ventured into a 3-week exploration regarding voting. We explored the questions: What is the power of elections? Who has the power to influence and participate in elections? How can my participation in elections influence/impact issues I care about? How will I participate in elections?

I relied on Zinn Education Project’s voting rights unit to dive into these conversations. In Lesson 1: Who Should Get to Vote, my students engaged in thought-provoking discussions around whether or not they (16- and 17-year-olds) are prepared enough to vote. The majority of them claimed they should be allowed to vote because they are impacted by those decisions. Students also debated if convicted felons should have power to vote. In our state of Illinois there is a bill awaiting approval that would restore voting rights to convicted felons.

In Lessons 2 and 3 students learned more about voter suppression and they then took that information to assess whether or not our communities are impacted by such actions. Students concluded this unit by brainstorming action items that they can engage in to try and combat voter suppression. Some examples included pushing more people to vote, contacting legislators, educating others on the matter, donating to organizations combating voter suppression, and registering to vote.

I will absolutely be using the “Who Gets To Vote” lesson this upcoming school year to supplement my existing unit on the Civil Rights Movement. As an AP US History teacher, it can be challenging to relay content in an immersive and active way other than direct instruction, but each time I use a lesson from the Zinn Ed. Project, my students come away more passionate about the topic and better informed. In this case, the questioning of the idea of ‘qualified voters’ will help both build on content already discussed, such as early political parties and land requirements to vote and democracy in action during Reconstruction and help students visualize how they prepare to be more engaged in current politics as they become voters. The inclusion of Fannie Lou Hamer’s perspective, as a Black female, only serves this particular lesson for the better. I appreciate how it includes a real perspective in order to challenge students’ existing thinking. As usual, the resources provided are meaningful, relevant, practical to implement, and classroom ready.

I used Ursula Wolfe-Rocca’s “Who Gets To Vote? Teaching About the Struggle for Voting Rights in the United States” lesson as part of a larger unit on voting rights in the United States. Specifically, I chose to use her primary source document about Fannie Lou Hamer’s experience with voting rights as well as her guided discussion about “Who Gets to Vote?” with my students. Students were first asked to respond to a question; “Who should get to vote” on a Padlet assignment. As Wolfe-Rocca describes in our own lesson, students had all kinds of qualifications in order to vote. The most common of those qualifications was a specific level of secondary education. Without that, many students argued, a voter would be uniformed, make unwise or reckless decisions, and therefore should not have the privilege of participation in the democratic process. After that discussion, we read Fannie Lou Hamer’s oral history of learning about the right to vote, and her struggle to gain the right to vote. It was a perfect follow up to the Padlet discussion.

My students are 10th graders at a predominantly white, upper-middle-class, suburban high school. Much of what Wolfe-Rocca described in our lesson came to the fore in my lesson. The ability to use Fannie Lou Hamer’s source materials allowed my students to gain an important insight that voting should have no qualification. Student’s thinking was indeed challenged. Many students reconsidered their preconceived notions that voting should have qualifications, especially around education and literacy, and that voting is a fundamental right in our democratic system. This lesson, and the other materials provided by the Zinn Education Project, really helped me move our discussion on voting rights forward.

I teach AP Gov and have wanted to showcase the struggle for voting rights to my students.

My favorite lesson in the Who Gets to Vote? Teaching About the Struggle for Voting Rights in the United States unit is the first one. I teach block classes, so I can spend ample time with students reading the excerpts of Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer’s testimony. A good related resource is the PBS Frontline documentary, “Fannie Lou Hamer: Stand Up”.

The second lesson provided the shock and awe for students to see how much voter suppression happens. The final lesson was such a great way for students to see and know what some have experienced when it comes to voting. The timeline was a great way to interact.

I am excited to teach the lessons again this coming school year.

I use the lesson Who Gets To Vote? Teaching About the Struggle for Voting Rights in the United States as part of a larger unit on Reconstruction in the United States. Being so close to Portland, we often use the city as an example of voting rights in terms of redistricting and who has a voice. Before getting into the materials, we make a class list of how students expect that policymakers might have restricted the right to vote for certain groups to thwart movements and laws that expanded voting rights. Once this is complete, I have students use the University of Richmond website to examine maps created around the time of the New Deal before finally examining the map of Portland that contains the language policymakers used at the time to justify what was considered a district and how that district should be communicated to others.

As students begin to realize that the map was drawn unfairly, and that many portions of the city were misrepresented, the dialogue between students typically picks up. We then discuss systemic discrimination and how it has contributed to modern gentrification in the city.

We finish our unit by looking at the current court cases surrounding redistricting and representation, as well as if felons should vote and how the Constitution protects voting. By understanding who gets to vote and why, students get a better grasp of who shaped the present and who will shape the future.

My students were shocked that they had all made it through eleven years of formal public education and had never learned about the work of Black suffragettes. The “Who Gets to Vote? Teaching About the Struggle for Voting Rights in the United States” lesson from the Zinn Education Project allowed me to celebrate this group of women in a way that fully centered on student participation and inference.

The structure of the lesson was incredible because it started with a very basic question of who students think should be able to vote. I had students complete a “big paper” activity where they silently wrote on chart paper the qualifications of an ideal voter. They had to keep writing while a one minute timer counted down, never stopping to list qualities and descriptions of voters. It was very interesting to see that no students specified the ideal voter by race; rather, they used terms like “all people” and “anyone.”

When we reexamined our charts in part two of the lesson, we made connections between what we had already studied in terms of southern politics and systemic racism to piece together why certain groups would have been purposefully denied the franchise.

Loved being able to lead a @ZinnEdProject session today for other district teachers! We did the voting rights mixer and it was a blast! So many great conversations and ideasfor implementing @CFB_Soc_Studies @mrschapman808 pic.twitter.com/gkqvy2mxOT

— History Gone TRUONG! (@truong_terri) February 14, 2020

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn