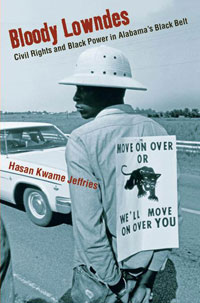

The story of Lowndes County, Alabama offers an excellent case study on the history of the voting rights struggle after the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. To bring this history to the classroom, we share here an article and interview with historian Hasan Kwame Jeffries, author of Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt. We have also included short excerpts from Bloody Lowndes on freedom rights and freedom politics, and a clip about Lowndes from the documentary film, Eyes on the Prize.

A Story Too Often Untold: Lowndes County, the Voting Rights Act, and the Birth of the Original Black Panther Party

By Hasan Kwame Jeffries

When 1965 began, African Americans in Lowndes County, Alabama could not vote. The county, which was 80% Black, had 5,122 eligible Black voters, but not a single one was registered. Denied the ballot, African Americans had no say in the political process. There were no Black elected officials and there hadn’t been one since Reconstruction. And no Blacks sat on juries since jury pools were derived solely from lists of registered voters.

The absolute exclusion of Lowndes County Blacks from the political process ensured that racial discrimination continued in every facet of local life. Public accommodations were separate and unequal. Public schools were rigidly segregated. And Black laborers, especially Black agricultural laborers, were overworked and underpaid.

Lowndes County Blacks had never been content with the status quo. Ever since emancipation, they fought hard for their freedom rights, the combination of civil and human rights that whites denied them during slavery. These included access to the ballot box, quality education, decent housing, land ownership, fair wages, and personal safety. But white supremacy was unrelenting, and its most vicious manifestation, racial terrorism, made direct, public challenges to the status quo impractical, if not impossible.

Indeed, long before 1965, Lowndes County, known to many as Bloody Lowndes, had developed a well-deserved reputation for racial terrorism. In the 1880s, whites defeated Reconstruction by stealing elections at gunpoint. At the turn of the century, they exploited Black laborers through sharecropping, convict leasing, and debt peonage. Early in the new century, whites lynched African Americans with impunity, fearing neither arrest nor prosecution, and concocted preposterous rape stories to justify these murders. Before World War II, they used brutal force to suppress the wages of Black agricultural workers, crushing, for instance, a 1935 sharecroppers strike by killing several people, beating dozens more, and forcing scores to flee the county for good. And after the war, whites, most especially county sheriff Otto Moorer, continued using violence to maintain Jim Crow.

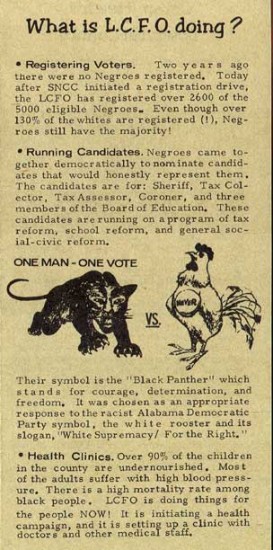

But things began to change in the early months of 1965. In March, one week before Bloody Sunday, a group of thirty-nine Black residents — some family, others friends — gathered at the county courthouse and boldly attempted to register to vote. No one was registered that day, but a movement was born. And by the end of the next year, this movement, led by local people and supported by daring activists from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), had transformed Lowndes County from a citadel of violent white supremacy into the center of southern Black militancy. They did this by creating the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), an all Black, independent, political party—the original Black Panther party. Their audacious bid to take control of county government was meant to ensure that Black people had a say in the decisions that affected their lives. It is a story too often untold.

The March 1, 1965 voter registration attempt energized African Americans in Lowndes County. To coordinate future registration tries, a small group met at Frank Haralson’s old shop on the edge of White Hall and formed the Lowndes County Christian Movement for Human Rights (LCCMHR). John Hulett, who spearheaded the initial voter registration attempt, agreed to serve as chairperson. William Cosby, a local shopkeeper, signed on as vice-chairperson. Elzie Lee McGill, a 59-year-old farmer, joined as treasurer, and his daughter, Lillian McGill, volunteered to serve as secretary. Jesse Favors, a railroad laborer, rounded out the leadership team as assistant secretary.

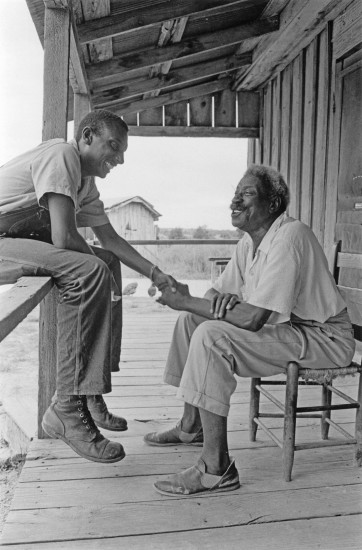

Stokely Carmichael in Lowndes County. Source: Library of Congress

The LCCMHR quickly set about organizing additional voter registration tries. As it did, four SNCC field secretaries, including Stokely Carmichael, a veteran of the movement in Mississippi, and Bob Mants, a native of Atlanta, joined them. The young activists came to the county just after the Selma to Montgomery march passed through, knowing they would find more than a few brave souls willing to fight white supremacy. And they did.

Operating out of a freedom house in White Hall provided by Black landowners Matthew and Emma Jackson, Sr., the SNCC activists helped local movement volunteers knock on doors from one end of the county to the other. They encouraged any Black folk who would listen — and even those who wouldn’t — to attend the twice-weekly mass meetings and to try to register to vote. The slow and hard work of canvassing paid off as more and more people joined the movement. In a remarkable display of collective courage, increasing numbers of Lowndes County Blacks overcame their resignation about the way things were and their fear of white violence.

Still, change came slowly. The county’s white registrars refused to add African Americans to the voter roll. As summer neared its end, they had added only a dozen or so African Americans out of the hundreds who had appeared before them. Meanwhile, large landowning whites began evicting Black renters who attempted to register, and white night riders began shooting into the homes of movement leaders. Then, on August 20, white resident Tom Coleman ambushed four movement activists leaving a store in Hayneville, killing white SNCC volunteer Jonathan Daniels. These were dark days.

The arrival of federal registrars in mid-August pursuant to the Voting Rights Act, which President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law earlier that month, provided local people with a glimmer of hope. For the first time since Reconstruction, they were able to register to vote. And within a few months’ time, more than two thousand did.

The Voting Rights Act was a major triumph, a product of the hard work and sacrifices of activists and ordinary people in Selma and far beyond. But it did not mark the end of the movement, either locally or nationally. It signaled instead the start of a new phase of struggle. Prior to the Voting Rights Act, movement activists fought to secure access to the ballot box. After the passage of the law, they fought to give meaning to newly acquired votes. In Lowndes County, SNCC’s Courtland Cox asked: “What would it profit a man to gain the vote and not be able to control it?” Encouraged by SNCC activists to think about nontraditional ways of empowering Black voters, the leadership of the LCCMHR decided to create their own independent political party.

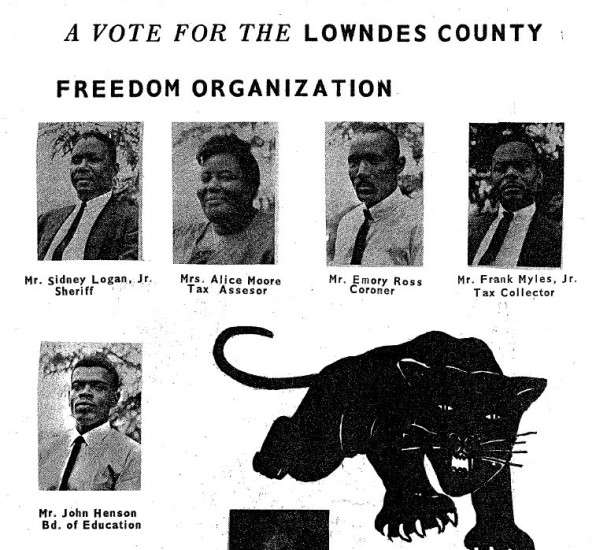

In December 1965, Hulett announced the formation of the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. Through the LCFO, local Blacks planned to run a full slate of Black candidates in the November 1966 general election. They aimed to wrest control of the county government away from white Democrats, whom local activist Frank Miles, Jr. described as “the ones who had done the killing in the county and had beat our heads.” The goal was simple. The task was hard.

In December 1965, Hulett announced the formation of the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. Through the LCFO, local Blacks planned to run a full slate of Black candidates in the November 1966 general election. They aimed to wrest control of the county government away from white Democrats, whom local activist Frank Miles, Jr. described as “the ones who had done the killing in the county and had beat our heads.” The goal was simple. The task was hard.

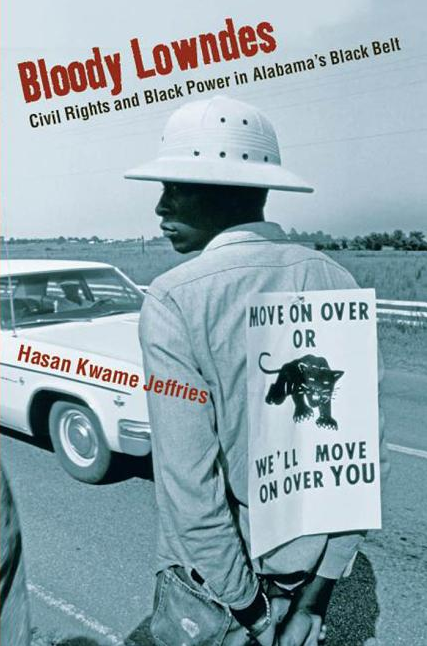

Because of Alabama’s high rate of adult illiteracy, every political party in the state had to have a ballot symbol. The ballot symbol of the dominant Democratic Party was a white rooster, which often appeared alongside the state party’s official slogan of “White Supremacy for the Right.” For the LCFO ballot symbol, local movement leaders chose a snarling black panther. LCFO chairperson Hulett explained: “The Black Panther is an animal that when pressured it moves back until it is cornered, then it comes out fighting for life or death. We felt we had been pushed back long enough and that it was time for Negroes to come out and take over.”

Local movement leaders and SNCC organizers valued voter education as much as voter registration, believing it would be harder for political candidates and elected officials, white or Black, to deceive an informed electorate. So they organized a series of political education workshops, held first in Atlanta and then in Lowndes County, at which they discussed and debated election law and the duties of elected officials. And for those unable to read, they produced and distributed cartoon storybooks detailing the same. It was a remarkable experiment in democracy.

On May 3, 1966, the LCFO held its candidate nomination convention. Despite the threat of white violence, nearly one thousand Lowndes County Blacks gathered at First Baptist Church in Hayneville and chose a full slate of Black candidates. They nominated Sidney Logan, Jr. for sheriff; Frank Miles, Jr. for tax collector; Alice Moore for tax assessor; Emory Ross for coroner; and Robert Logan, John Hinson, and Willie Mae Strickland for school board. “We have our candidates,” said SNCC’s Carmichael that evening. “Their names will be on the ballot November 8 along with our symbol, the Black Panther. All the people have to do is pull the lever under the panther. November 8 we vote. November 9 we take over the courthouse.”

Lines of people standing outside buildings in Lowndes County, Alabama, on election day, Nov. 1966. By Jim Peppler Southern Courier. ADAH.

Local activists and SNCC organizers spent the summer of 1966 mobilizing the newly enfranchised Black electorate. And on November 8, they turned out in great numbers, with some sixteen hundred African Americans casting ballots for Black Panther candidates. But it wasn’t enough. Whites used fraud and intimidation to suppress Black voter turnout and to pad the Democrats’ vote totals. When the final ballots were tallied, every LCFO candidate lost, some by just a few dozen votes.

Although the LCFO fell short of its most immediate goal, the people weren’t defeated. “November 8, 1966, made one thing clear,” remarked Carmichael. “Someday Black people will control the government of Lowndes County.” And so the people pressed on, organizing not just for electoral victory, which eventually did come, but also for better schools, access to capital, jobs, health care, and personal safety.

Reflecting on the local movement, Carmichael explained: “Lowndes is not merely a section of land and a group of people, but an idea whose time has come.” That idea — the development of independent political parties to empower African Americans — an idea at the core of Black power politics was one of the key political developments of the post-Voting Rights Act era. And like the snarling black panther, it was born in rural Lowndes County.

This article was reprinted by permission of the author from Bridges: The Story of the Voting Rights Struggle in Selma & the Black Belt (Imani Press, 2015).

Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt (Excerpts)

Freedom Rights and Freedom Politics

In the pages ahead, I tell the story of the Lowndes County freedom struggle. My purpose is fourfold. First, I aim to provide a more comprehensive framework for understanding the civil rights movement. This new paradigm revolves around the concept of freedom rights’ the assortment of civil and human rights that emancipated African-Americans identified as the crux of freedom. Framing the civil rights movement as a fight for freedom rights acknowledges the centrality of slavery and emancipation to conceptualizations of freedom; incorporates the long history of Black protest dating back to the daybreak of freedom and extending beyond the Black Power era; recognizes African-American’s civil and human rights objectives; and captures the universality of these goals. Moreover, it allows for regional and temporal differentiation, moments of ideological radicalization, and periods of social movement formation.

In the pages ahead, I tell the story of the Lowndes County freedom struggle. My purpose is fourfold. First, I aim to provide a more comprehensive framework for understanding the civil rights movement. This new paradigm revolves around the concept of freedom rights’ the assortment of civil and human rights that emancipated African-Americans identified as the crux of freedom. Framing the civil rights movement as a fight for freedom rights acknowledges the centrality of slavery and emancipation to conceptualizations of freedom; incorporates the long history of Black protest dating back to the daybreak of freedom and extending beyond the Black Power era; recognizes African-American’s civil and human rights objectives; and captures the universality of these goals. Moreover, it allows for regional and temporal differentiation, moments of ideological radicalization, and periods of social movement formation.

Second, I strive to offer new insights into the mechanics of the civil rights movement. The struggle in Lowndes County elucidates the movement’s key organizing elements, including recruitment efforts that tapped into the Diaspora of Black southerners who migrated north. It underscores the breadth of Black protest, which extended far beyond voting rights. It draws attention to the special character of grassroots insurgency in the rural South. It highlights the outside forces that affected movement activism, especially white resistance and federal involvement. It helps explain the demise of movement organizing. And it complicates the movement’s standard chronology, partly by underscoring the importance of exploring Black protest in the post-Voting Rights Act era. [From Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt, page 4.]

* * *

At the moment of emancipation, [African Americans] reflected on their enslavement and identified their freedom rights, or those civil and human rights that slaveholders denied them. These rights included those enumerated in the U.S. Constitution and in various state constitutions, such as freedom of speech, religion, and assembly, and the right to due process, keep and bear arms, and vote. They also included rights that everyone is born entitled to, such as the right to own property, choose employment, enjoy economic security, marry and start a family, move without restriction, and receive an education. African Americans recognized the importance of freedom rights during slavery. Their bondage made clear that freedom rights were not only essential to living meaningful lives, but also the key to power within society. The violence of slavery, however, circumscribed their efforts to secure these rights. Only after emancipation were they able to claim them publicly. Unencumbered by the shackles of the Peculiar Institution, they insisted on a decent standard of living, pushed for social autonomy, pursued basic literacy, fought for political power, and sought protection from white violence. Even after the euphoria surrounding the jubilee subsided, their primary focus remained the guarantee of freedom rights. [From Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt, page 8.]

* * *

The Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) convention was a memorable event for the Black community, which had not hosted such a gathering since Reconstruction. It was equally important to SNCC’s Alabama organizers, who had worked tirelessly to create a grassroots third party to provide an alternative to the Democratic Party. The significance of the LCFO convention, however, transcended its local meaning. The selection of seven African Americans to run against white Democrats in November 1966 was a triumph for democracy. Although there was nothing particularly radical about the candidate selection format, the process of political education that African Americans underwent leading up to the convention cut completely against the grain of American politics.

After the 1965 Voting Rights Act became law, SNCC organizers developed a unique political education program for Lowndes County residents that used workshops, mass meetings, and primers to increase general knowledge of local government and democratize political behavior. As a direct result of this effort, the emerging Black electorate rejected the undemocratic traditions that defined American politics. Rather than promote the interests of the socio-economic elite, draw candidates exclusively from the ranks of the propertied and the privileged, or limit decision making to a select few individuals, they adopted a freedom rights platform, selected candidates from the poor and working class, and practiced democratic decision making. In this way, the political education process gave rise to freedom politics. This new kind of political engagement coupled the movement’s egalitarian organizing methods with the people’s freedom rights agenda. The embrace of freedom politics by third-party supporters made the LCFO convention the high point of the Lowndes movement. [From Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt, page 145.]

Talk by Hasan Kwame Jeffries About Bloody Lowndes

Related Articles

SNCC, Black Power, and Independent Political Party Organizing in Alabama,1964-1966 in the Journal of African American History (Winter, 2006).

Remaking History: Barack Obama, Political Cartoons, and the Civil Rights Movement by Hasan Kwame Jeffries from Civil Rights History from the Ground Up: Local Struggles, a National Movement by Emilye Crosby (University of Georgia Press, 2011).

Hasan Kwame Jeffries is associate professor of history at the Ohio State University, where he holds a joint appointment at the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity.

Film Clip on Lowndes from Eyes on the Prize

I am one of the student that was attending Tuskegee Institute and working at White Hall Baptist in 1966. the KKK use to chase us every night when we would dismiss .I am now a mother and a grandmother who will not allow my children to attend school on their Bday until they register to “VOTE”