On April 8, 2024, historian Julius B. Fleming Jr. spoke with educator Jessica Rucker about his book Black Patience: Performance, Civil Rights, and the Unfinished Project of Emancipation.

On April 8, 2024, historian Julius B. Fleming Jr. spoke with educator Jessica Rucker about his book Black Patience: Performance, Civil Rights, and the Unfinished Project of Emancipation.

This session was part of our monthly Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online class series. Don’t miss the rest of the spring lineup — register now.

Participants shared what they learned and the impact of the session:

Tonight really reinforced for me how the arts are a vessel of expression and resistance that transcends structures of oppression. The arts are the voice of the people!

This session was excellently done. I especially appreciate how I could use things I had learned in previous sessions to help inform tonight’s session. (Specifically, the discussion of how art moves change. This ties in beautifully with the last session about the power of Black music and musicians who pushed boundaries.)

Every moment was moving, informative, and powerful.

I loved learning that there are “no perfect radical histories.” We each have a role to play in the revolution and each of our subversive actions makes a difference.

Today’s session helped me better connect to the ways in which time is used as a weaponized concept against Black freedom and liberation. The expectation of patience and the demands placed on Black people to “wait for change” to advance in a way that was palpable for white people continues today.

Dr. Fleming had many amazing lines that stood out to me, particularly about white supremacy being so ingrained that we don’t need white people.

Black patience is a tool and vestige of white supremacy; it’s a part of the afterlives of slavery.

What really stood out to me was the whole history of patience. I see it in today’s world all the time. Why should my students wait and accept waiting?

It was all wonderful. I love these times to learn, think, and talk together.

Event Recording

Recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jessica Rucker (she/her): For those who don’t know, I’m a student right now, and I had the great opportunity in the fall of 2023, just this last fall, to enroll in Dr. Fleming, or Julius’s, course. We had the opportunity to read Black Patience: Performance, Civil Rights, and the Unfinished Project of Emancipation. So, let’s just start off. Julius, what is Black Patience?

Julius B. Fleming Jr.: Before I jump in, I just want to say thanks to the Zinn Education Project for having me. Also, thanks to you, Jessica, for being in conversation. You really clarify for me how any good teacher has to also learn from the student, and you taught me a lot. So thank you for that.

Black Patience, where would I start? So, I was doing research for this book — at the time, it was a dissertation — and I knew that I wanted to study the 1950s. I knew I wanted to study the Civil Rights Movement. At the time, I was reading novels and poetry and all sorts of things, and I came across plays. I noticed that what connected all of these things was this insistent demand for freedom now.

So, I just started to wonder why are all these Black people demanding freedom now? Why aren’t they saying let’s work toward freedom? Why aren’t they saying freedom will eventually arrive? They want it now. They had to have been responding to something. So, as I started to study, I realized that there was this call, particularly from white people, for Black people to go slow, and not only to go slow, but to be patient.

Rucker: The book for me really looked at race, but also time and violence. And that’s how I came to understand Black Patience, this way in which the white supremacist state wanted Black people to slow up for this thing called freedom, be patient. So, this thing that could be considered very virtuous was being weaponized against Black people.

I want to stay here with Black Patience, but I’m thinking a little bit right now of Saidiya Hartman; she has this idea that slavery has afterlives. So, based on your description of Black Patience, I think Black Patience is actually one of slavery’s many afterlives.

With that in mind, what did Black patience look like or sound like or feel like from Emancipation through the 1960s. In other words, please share some examples of what Black patience might look like in action. What does it mean for Black people to be told to go slow?

Fleming: I love that connection that you’re making between slavery and what Hartman calls slavery’s afterlife. Which is just a way of saying even though slavery has been legally abolished, what are the effects of slavery? How does slavery reverberate into the present moment? So, during slavery, I was interested in all of these moments where Black people, where Black bodies, had to wait.

If we go back to the west coast of Africa, for example, they were forced to wait in slave castles before they were then put on the ships, the slave ships that would then carry them across the Atlantic to the New World. They were forced to wait in the belly of those ships for months as they made that transatlantic voyage, the Middle Passage. Then they were forced to wait on the auction block, for example, as they were being sold. Once they got to the plantation they had to wait for permission from their master to even leave the plantation. In other words, in slavery there was already this long history of waiting that Black people had been subjected to.

Now that we are in the context of Emancipation, and Black people are starting to argue for freedom, already in the 19th century there’s this really robust conversation about why Black people need to wait, why we can’t go too fast. Why we can’t move too quickly toward making Black people human, or citizens, when they’ve been a slave. The argument was that society just isn’t ready for it; white society just isn’t ready for it. In the 19th century, they also can lean into this kind of Christian discourse of just “wait on the Lord,” which, obviously, a lot of enslaved folks were into for a number of reasons.

But, by the time we get to the middle of the 20th century, there’s an important year in the 1960s, and that’s 1963. That’s the Emancipation Proclamation centennial, or one hundred years since Abraham Lincoln signed that document and Black people across the United States obviously, but Black people around the world too, are saying, “We have been waiting for a long time, and that freedom hasn’t come yet.” This is what they’re picking up on, and this is what ultimately leads to them demanding freedom now.

Rucker: I love it, and I’m with it. Tell me a little bit more. I like what you mentioned, the language of waiting. What’s the difference, based on your reading of these novels, these poems, these plays? How are you thinking about the difference between patience and waiting, and why is it important for educators to make this distinction when they’re teaching about the Black Freedom Struggle?

Fleming: That’s a good question. Initially, the book was called The Waiting Room, and I was advised that people may think it’s a book about a hospital. But I was really into waiting.

Rucker: Listen, this democracy does need to be triaged.

Fleming: It does need to be triaged. And Black people are forced to be patient in waiting rooms across the country, leading to all kinds of mortalities. It’s real. But, as I was doing the research, patience kept coming up, not only from Black people who were saying, “We don’t want to be patient,” but white people themselves were asking Black people to be patient.

For example, President Dwight Eisenhower, in speeches throughout that era, specifically asked “the negroes to be patient and to wait” because society wasn’t ready. In other words, patience was a part of the language white supremacists were using to demand that Black people wait. The other part of it is that when we think about the difference between waiting and patience, I’m thinking about my mother, when I would want something, she would say, “Wait on it.” I had a Mississippi mother, so even if I didn’t want to wait a certain way, I had to look like I was happy to wait. That’s when we move into the terrain of patience, because patience means to wait willingly, to sacrifice willingly, to willingly engage in long suffering without the attitude. So, a part of what the book is saying is that white supremacy not only wants Black people to wait, but they want them to wait a certain way. They want it to be virtuous, and [for there to be] a willingness to wait that then rises to the level of patience.

Rucker: Right on. And the Black people are not waiting, we’re not Waiting for Godot. We’ll come back to Beckett’s piece in just a minute. In the book, you make it clear that Black people are making insistent demands for freedom now throughout the Civil Rights Movement, but also the long Black Freedom Struggle. So, why is that slogan so important? What does the practice of freedom now tell us about the relationship between time and Black life in the Civil Rights Movement? Also, tell us what’s happening in the United States in terms of modernity, speed, and acceleration, and why does this seem like a paradox?

Fleming: We have to think about this 1950s, 1960s moment, and to go back to Eisenhower. This is a moment when he authorizes one hundred million dollars for Congress to establish NASA because he wants to beat the Russians into outer space. At the same time, we have trains that are going faster, we have airplanes that are going faster, we have new systems of finance that can move money across the world faster, [and] we have television that can make information travel at record speeds. In other words, the whole pace of the modern world is speeding up. Eisenhower supports this. At the same time, he’s asking Black people in several speeches to be patient and to wait. He says that we cannot go too fast in what he called this “delicate field” that involves the emotions of so many. A part of what happens then is that Black people are asked not to be in line with the pace of the modern world. As things are speeding up, they’re being asked to go slower. And they recognize it. This is a part of why they say we will not wait, because we see the trick that is at work here.

Rucker: In the 1950s, if I understand what you’re saying, when my grandmother would have been finishing up her secondary learning experiences, it was quicker for the United States to put a person in a spaceship to go to the moon than it would have been for her to be in a setting where she had equal access to learning materials and books. Is that what you’re saying? So, we can go fast in all these other areas, but when it comes to Black people having access to their freedom rights, that we’ve got to take time.

I wonder if any teacher comrades on the line can relate to that. You’re asking whether your local or internal administration, or the broader school system, for some changes that you know are going to support your students. But they say, “Hold up, we’re working towards that.” I love how in the book you talk about how Black people are pushing back against that.

I now want to look at the role of Black cultural workers, because I think your book Black Patience does an excellent job teaching readers about the role of Black theater workers in particular, and how they help to speed up time and spread this collective demand for freedom now. Or, in the words of Dr. King, how Black theater workers helped time. I don’t think I’d ever thought about Black theater workers as freedom fighters in quite the way that your book helps me do that. Let’s start there. How did Black theater folks in the Black Theater Movement at the time help speed up and spread this collective demand for freedom now?

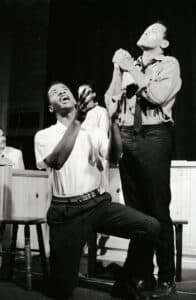

Fleming: In the same ways that all other civil rights activists were doing this work, Black cultural workers, Black artists, were also doing this work with their art. For example, in the book I write about the Free Southern Theater. This is a Black theater that was established in Mississippi, which in many ways is the belly of anti-Black oppression and white supremacy in the Jim Crow South. And yet they started this theater because they said if theater could have any political meaning anywhere, it’s in Mississippi.

A part of what inspired them to start that movement was that they had seen a production of Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot at Alcatraz prison, and they said, “If this play can have meaning at Alcatraz, it can have meaning at that larger prison, Mississippi.” So they started this theater.

What’s so crucial about that for me, while I was writing this book, we teach the Civil Rights Movement through the sit-ins, through the jail-ins, the marches, the speeches from Dr. King. I you actually go to the archive, if you actually go to the records that were left from the past, you see that these theater workers were right there; they were right there, they stayed with the SNCC activists. They had bombs thrown at the stage while they were performing. They were subjected to police brutality.

In one instance they were performing in Beulah, Mississippi, and they were taken to a police station and the police officers asked them questions like, “How is that white pussy, boy? How does it feel to screw a white woman?” All of these questions, and then they released them, and they caught the Ku Klux Klan and told them to pick them up. So they had to crawl along Mississippi roads, hiding in weeds, to dodge the Ku Klux Klan, and luckily they survived.

Alongside something like that, Jessica, when they applied to work with the Free Southern Theater, they were asked questions on the application like, “Can your family afford to pay a $500 bill in the event that you are arrested?” This is 1960s Mississippi. Among a lot of working class Black folk $500 is a lot of money. So, this just points to the immense danger that these artists were in, how they sacrificed life and limb to participate in the movement in the same ways that other activists were.

Rucker: This is really, really powerful. You talked a little bit about why Mississippi became the ideal stage, so to speak (no pun intended), for the Free Southern Theater. Tell us a little bit about how it came to be, because in the book you also do a great job teaching me about the Mississippi Free Press and the role of Tougaloo College. How are the Mississippi Free Press and Tougaloo College connected to the Free Southern Theater, and why is Mississippi so important? How does where this is taking place change our minds about the Civil Rights Movement in terms of who we see as the architects moving the movement forward?

Fleming: I’m sorry, I just saw Judy Richardson’s name in the chat, so I’m having a little bit of a fanboy moment, so you’ll have to forgive me.

Rucker: Judy!

Fleming: I’m from Mississippi, so obviously I’m biased. And obviously we know how Mississippi circulates in people’s minds as backwards. In fact, when one of the Free Southern Theater actors landed in Mississippi, Denise Nicholas, she said, “I felt I had landed on another planet. I felt alone and scared.” Nina Simone; everybody knows about “Mississippi Goddam.” Tennessee is bad, Alabama is bad, but Mississippi was in many ways just a bastion of inequality. So the fact that they’re able to do this work in Mississippi means a lot.

What’s so interesting about the theater being started at Tougaloo, is I graduated from Tougaloo College as an undergrad and I never heard of that theater the entire time I was there. So, a part of what I was trying to think about then was why is it that these histories of theater and the Civil Rights Movement are so suppressed. How can I move through this campus for four years [and not have heard of this]? My wife also graduated from Tougaloo, and neither of us ever heard about that theater one time.

Rucker: Wow! You talk about [Gilbert] Moses, [John] O’Neal, and [Doris] Derby, and I think if I’m looking in the chat, Adam [Sanchez] was asking a question and Judy responded. Judy, do you want to jump in and share a story, because there’s parts in the book where those relationships get woven together? Do we have, Judy?

Richardson: I’m here. First of all, thank you so much for this book. I cannot wait to read it. And honey, anybody who writes from Mississippi about the theater and about Black patience is my person. So thank you. But no, in terms of the theater, as far as I know John O’Neal and Denise and Dpris Darby, I don’t think it came out of the role-playing, as Adam Sanchez had just asked.

But what was amazing to me is that they would be doing these plays — of course, like Godot and all — I mean plays that I had difficulty understanding. The sharecroppers coming out of the fields had no problem. They saw the relationship with having to wait. They saw the relationship with who was the master and who was supposed to be the servant. They got the relationships and they automatically translated it to their own lives, and that’s what was amazing to me, in a way that I could not.

Fleming: That’s right, absolutely.

Rucker: I want to stay there. That’s such a powerful point. I remember being in high school and reading Waiting for Godot and being like, “Godot don’t come? What’s up with that?” I think there’s something really brilliant about Black people staging this particular play. You talk about how, whether it’s cotton fields or front porches, it really challenges this idea of who’s doing the intellectual organizing.

When I think about being a high school teacher, there were ways that I was asked to track and cluster students who are going to be our high performing students, but there’s something about reading what Black folks are doing with plays, or even Ossie Davis’s Purlie Victorious. Or In White America.

I would just love to hear some stories about what it was like, not just for the folks staging and performing in these plays, but what it was like for folks to experience these plays. And what was the response? You were starting to talk a little bit about that, but Black people in theater are doing some heavy, critical thinking. Not just the performers, but, again, the people in the audience. I think this is important for us to think about as classroom teachers, when we think about even what a text is.

Fleming: We were talking about how education is coming under attack, how knowledge is coming under attack, and how art is coming under attack. There’s a reason why books by Toni Morrison and others are being banned, because folks in power recognize the transformation of consciousness, the new ways of seeing the world that are opened up through art. This is exactly what happened when the Free Southern Theater was working in the Mississippi Delta. As Judy was saying, most of these people actually were sharecroppers. Many of them didn’t even have an eighth grade education.

When I was doing research, there were the theater’s recorded notes. They would write things like “negro lady and audience says this play makes me think about. There’s a master slave dual in the play, and at one point the slave takes the rope off of his neck, and the negro lady says, ‘Oh, this makes me want to take the rope off my neck.’”

Fannie Lou Hamer was at the performances in rural Mississippi, and she stands up at the intermission, and also once the play had ended, and she says that we are like these men, waiting for Godot. The reason the negro is as far behind as he is is because we’ve been waiting.” What’s so interesting is that white journalists will come down from New York because they were so fascinated by the possibility. They assumed that Black people from Mississippi couldn’t understand these plays. What they didn’t talk about was that when the play opened in Miami a lot of white people didn’t even get it. So when they came, like Judy, they were astonished that these Black people got that play.

Rucker: Yeah, right on. Judy, do you want to share one more story?

Richardson: There’s a way that we use all the forums that are at our disposal to get our lives out there, because we have been so misinterpreted, and all that stuff that we know. So, the main thing is that we are now through all of these things, the Free Southern Theater, the photography, and it’s all the ways that we have our voice again.

Rucker: I love this polyphonic conversation, because I think it’s important that your lived experience is in conversation with the lived experiences that Julius was able to excavate. Julius, do you want to say anything else about Waiting for Godot, because I want to talk a little bit about “Kicks & Co.”?

Fleming: Yeah, one last thing I’ll say about Waiting for Godot is that sometimes we want perfect radical histories. There were moments where, for example, SNCC activists said about the Free Southern Theater, “We don’t have time for this. We’re staging voter registration drives. They’re running around with their props in their wagon getting in the way of the movement.” Also, there were little kids at the performances who threw spitballs at the stage. There were some people who walked out because the play bored them. The last thing I’ll say is that I don’t want to suggest that all of a sudden all Black people in Mississippi were digging what the Free Southern Theater was putting down. We’re human, and so some people weren’t biting what they were trying to feed. That’s important to note.

Rucker: Thank you for that.

Fleming: Judy, there was one story when I was doing research, an old man who lived in a shack not too far from Fannie Lou Hamer. While they were staging Waiting for Godot he turned his lawn mower on the entire play to drown out the sound of the play to let the white people know that he wasn’t on board with it.

Richardson: It’s amazing that it still survived, that people still came in the same way that they still came down to vote even after people were beaten. They still kept coming; they never stopped. That’s the beauty of your book.

Rucker: Wow, thank you. The cool thing is that Black theater workers were not only staging and interpreting plays written by other folks, there were Black folks who were writing what you describe as a civil rights themed musical. I was like, oh, shucks, that’s a new genre for me. So, talk a little bit about “Kicks & Co.” Who wrote it, how was it received, and why is this story also important to teach about the Civil Rights Movement?

Fleming: That’s a good question. Black people love music. In the Civil Rights Movement, music was just so important at the meetings, the marches, those sorts of things, and so a lot of Black artists felt that they wanted to tap into that energy and write musicals because it was such a part of that political moment and a part of Black culture. Also, music was a way for Black communities to come together.

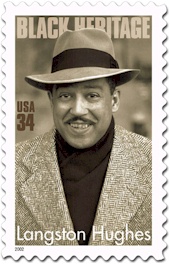

Langston Hughes wrote a play called Jerico-Jim Crow, a musical. There were some white audience members who were like, “I don’t understand why these people are singing in the middle of the play.” Hughes says this is the point: We want them to interrupt or disrupt the performance, we want the call and response to invite them to participate. So, we see how, even before the Black Arts Movement, this Black aesthetic is already at work.

Oscar Brown Jr., the play you mentioned, there’s a very similar thing. Of course, he’s known for his music, [but] he also has this identity in Chicago as an announcer. But this was supposed to be the big Black playwright after Lorraine Hansberry. This was supposed to be it. It raised tons of cash. But the white critics called it quote, “a surefire contender for Broadway.” Sammy Davis Jr. saw the play. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. saw the play and he wrote a letter to Sammy Davis Jr. talking about how good it was, and how it shows what art can do for the Civil Rights Movement. But, when those white audiences got to the theater and they saw how radical that play was, it didn’t make it out of Chicago.

Rucker: This is powerful. The way I interpret this is, it could get great feedback from folks at Teaching for Change, my folks at the Zinn Education Project, [and] from the SNCC Legacy Project. But if I come in there really serving that fire, my employers might say, “Wait, Jess, you took it too far. When at first you were just coming in here smelling like cocoa butter and talking about whatever it was fine, but now you’re going a little deeper.”

It’s okay if we don’t have a long run, so to speak, because that might not mean that we’re not doing the work that we need to do. But it might mean that we are working on the work so that we can keep this movement going. That’s what that play really really taught me, and it challenges how I think about the long Civil Rights Movement. Even if something doesn’t last for a long time, it doesn’t mean that the impact isn’t lasting.

Fleming: That’s right. If I’m being honest, part of what frustrated me is that I encountered a lot of historians who assumed that this work wasn’t going on. They were saying things like, “The 1950s and 1960s weren’t radical.” And I’m like, “People were fired from their jobs for voting. People were murdered. They had bombs thrown at them. What’s not radical about that?” A part of what they argue — and this is the long Civil Rights Movement argument — is that if we really want radicalism, we have to go back to the 1930s and 1940s Communism. What that move does is to say that the people who are really radical are white communists. That’s a problem, because I want to think about those Black people in the 1950s and 1960s who sacrificed everything for the movement. We can’t write them out of history.

The last thing I’ll say about “Kicks & Co.” is that it’s important for us to know, to your point about maybe they accept the teaching or the syllabus, or the text selection at first, but then it’s a little too radical. Lorraine Hansberry worked with that play, and we have to keep in mind that just years before 1959, her play was everything. America loved that play because they misread it. The critics, even the FBI, surveilled that play. They were in the audience, and the FBI agent basically said, “Hey guys, we don’t have anything to worry about. It’s just a play about what he called negro aspirations.” He missed all the deep radical messages. So, when Lorraine Hansberry decided to work with “Kicks & Co.” the white community was relieved, but what they got was something radically different.

Rucker: We singing “Wade in the Water,” and it’s perceived that we are just happy singing, but really we’re laying down the tracks, we’re coding the message for how to steal away home. So, I really appreciate that there’s more than one way to read radicalism, and there’s more than one way to teach the Black Freedom Struggle. I hope that folks who are educators and teacher educators are also thinking about the social studies element, the ELA element, and also the arts element. Whether I’m a classroom teacher who teaches science and chemistry but has a love for theater and art, I’m also thinking about how, outside of my classroom, I’m using extra curricular spaces to also continue to teach the Black Freedom Struggle.

That’s what I really love about Black Patience, what teach me about performance. I think you just did such a great job at looking at the ways in which repetition is a way to either keep things the way they are, or whether repetition can be used to unsettle and challenge power structures and domination in a way that I think is very important, as I think about teaching the Black Freedom Movement.

Fleming: I think that’s a great question, because repetition is important. The minute slavery is abolished in this country — you talked about the afterlives of slavery — those people got to work figuring out ways to keep Black people oppressed, like the chain gang. They came up with laws like loitering laws, which basically said that if Black people were hanging around they could be arrested, and once they were arrested they would put on a chain gang. They would then be put on a chain gang to do work for white capitalists, to make money in the ways that they did during slavery. And in that way white supremacy repeats itself.

So, we shouldn’t be surprised that after the Civil Rights Movement we get the rolling back of those gains. Or after affirmative action, we get the rolling back of those gains. Or after Barack Obama, we get everything that we have now. It repeats itself. But also, the thing I love about Black art is that it also repeats itself.

If we think about a play like Waiting for Godot, yes, there were the Mississippi Delta audiences during the Civil Rights Movement, but also when Hurricane Katrina hit and those Black people in 2005 were left to wait on their house roofs for the federal government. What play did those Black activists turn to to talk about waiting? It was Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. In Haifa, in Japan, all around the world, this play is being used in radical ways. There’s also the repetition of radical art, which I think is important.

Rucker: We just keep coming back. This is beautiful.

[Breakout rooms]

Rucker: Before I bring Julius back to ask a few questions, I’m going to ask people to light up the chat. I heard some great thoughts about incorporating “Kick & Co.” portions of the play, doing some close readings in an ELA classroom. That is a brilliant idea, and I will be remiss, I was reminded that our namesake, Zinn, wrote three plays. Zinn wrote plays because he saw and he believed in the transformative power of art and art for political and social activism and transformation.

The last thing I want to do is underscore some points and recap. Black theater was a space in which Black people rehearsed and staged Black freedom and liberation. Black theater and Black theater workers were critical to the success of the Civil Rights Movement and helped engage a base of people who might not have otherwise gotten involved in the Black Freedom Movement through activism and organizing. [This is just to] clarify what we are talking about in the context of Black patience from the first half, because we are going to talk a little bit about another way that Black patience can be thought of. But Black patience from the first half of today was really naming the ways that time is weaponized against Black people, the ways in which virtues like patience are weaponized against Black people, forcing us to repeatedly perform waiting as a criterion for their freedom. So, through thinking about Black patience, it shows how theater was used to perform a different style of freedom and liberation, through intellect for sure, but also art and creativity in ways that go hand in hand with the sit-in movements, the Freedom Riders, the jail-ins.

With that said, I want to go to the 1960s. One of the things, Julius, that I really appreciate your book for is that it helped me understand that the movement is a lot deeper and a lot wider than I thought. It really challenged me to think more about who was participating and how they were participating in the Black Freedom Struggle. With this deeper and wider understanding of the Black Freedom Movement or the Black Freedom Struggle, how might educators, students, [and] educator allies on the call today, take up this history and implement its lessons today? In other words, how can the lessons from Black Patience help us imagine how we can use art and culture to engage socially and politically during this particular climate?

Fleming: That’s a good question. I think I’ll start just by thinking about theater as an art form. In the 1940s and 1950s, we had these great novels by Black novelists like Ralph Ellison and Richard Wright. In the 1950s and 1960s, we do have Black novels, but they don’t rise to that kind of iconic level. There’s a reason why; there’s a lot of investment in theater because the Civil Rights Movement is at a boiling point, and Black people turn to theater because it’s an art form that allows them to be together in community.

In theater studies, there’s this Latin term that we use called communitas, and it basically thinks about the ways in which theater invites people to come together in community. Mississippi was coming together in cotton fields, for example, or around the back porch of a shack. So, as we think about this moment, we’re going to need a lot of, not people reading individual novels (we need that, too), but we need a lot of art forms that allow us to come together, to use art to think through a problem in the ways that they did during the Civil Rights Movement. Also, theater as a strategy of teaching. I’ve done some high school classroom visits when I visited colleges and students, I gave them a little assignment to work together to do a little theatrical exercise. They love coming together as a way of learning. So using theater as a tool to teach, I think, is also important.

Rucker: Thank you. Right now, scores of teachers — and librarians especially, but not exclusively — are being forced out of their classrooms, forced out of libraries, and being fired, some because of their commitment to teaching a people’s history of the United States. In many ways, they’re being surveilled and confined for standing in service to Black freedom and democracy for all.

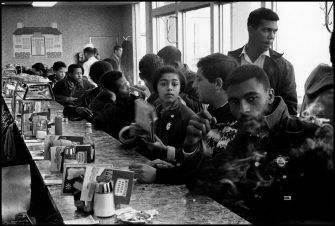

This really reminds me a lot of freedom fighters like Ruby Doris Smith or Diane Nash, who joined the sit-in movement, they participated in the Freedom Rides, they got arrested, and then they refused bail. So, in essence, those two, Doris Smith and Nash, and other civil rights activists, used the jail-in strategy to push back against the violence of white resistance to Black freedom, but also the violence of being incarcerated for demanding freedom now. How did they use that jail-in strategy, and how do they respond to being incarcerated? And how do they subvert Black patience through their incarceration in the violent ways that time and space had been used against Black people?

Fleming: That’s a good question. So, during the Civil Rights Movement, Black people were really careful not to appear too radical, not to appear too quote unquote “Black,” because there were all of these stereotypes circulating about Black people, in ways that still circulate today. They were violent; they had quick tempers.

Someone mentioned role-playing earlier. SNCC and other organizations rehearsed how to remain patient in the moment of protest, how someone can pull your hair and you remain patient. Part of what they wanted to do was to respond to sheriffs like Bull Connor. This is really the early moments of mass incarceration. They said that because these Black people are so interested in being moral, we’re going to throw them in jail because Black communities don’t like imprisoned folk. They were going to start to take some of their moral authority.

But what Black people did during the movement was to actually transform the very meaning of the jail, so it’s not this container, this badge of shame. It was an honor to go to jail for the Civil Rights Movement. You mentioned Diane Nash. She had a trial, and the judge decided not to send her to jail. She was upset. She’s like, “I want to go to jail,” because she wanted to use waiting as a way to push back against Black patience.

So, to the second part of your question, where in the book I think about the sit-ins and jail-ins and I asked, “How do Black people turn Black patience on its head? How do they wait in that jail, and perform a kind of Black patience to disrupt Black patience?” It makes me think about my grandmother, actually. When I was growing up, she used to tell us, I’m an oldest grandchild of 21, and because I had to protect my cousin sometimes, I have a bit of a temper. If you mess with my family, sometimes I would tell people what I would do to them if they messed with my family, and my grandmother said to me, she said, “You have to talk less, and if you’re going to flip the world, don’t let them know until they’re flipping.” That stuck with me. It was about waiting; it was about lying in wait before you stage the attack. That opened up ways for me of thinking about how waiting can also be radical.

Rucker: That’s powerful. For folks who know me, I bring my ancestors — my grandmother, my great grandmother — here with me, and what you just shared was so powerful like that. That’s political wisdom, what your grandmother taught you, and it’s making me think a lot about our benevolent ancestors, and how this work of challenging Black patience, subverting Black patience, let’s us let them know that their organized efforts for freedom were not in vain. Instead, their freedom desires and their freedom fights live in our veins, and it can be performed in so many different ways. I think that’s what I was also trying to get at earlier with the Black body. The Black body is also a resource that we can use in our movement for freedom, just by how we do or don’t wait, or whether we move literally through protesting, or whether we move through the gestures that we embody on stages, as well.

Fleming: You mentioned teachers who are being fired, and for teaching certain things. I think it is important, especially as we think about activism and education, that we strategize. There are people who perhaps might have to play or might be comfortable playing the role of outward agitator. But we also need people, and I’ll just be frank, I was criticized by graduate students. I began my job at the University of Maryland when Freddie Gray [was killed by police] in Baltimore, and they were asking, “Are you going to march in the streets?” I’m a realist. I’m a heavy set Black man with locks and earrings. They don’t see my Penn PhD. They don’t see an ivy league PhD. They see a Black man with locks. Same thing when I was in graduate school with the Occupy Movement; there were certain ways that I had to participate because of how I’m embodied. I was the only Black man when I started my job, and the only Black tenured track male professor in the department of 76 professors. So, there were things that would happen, and I would say to myself, “Well, I can be loud and I could protest in this way, or I can be strategically quiet and I can move pieces without them ever knowing that the pieces are being moved.” And I’ve seen the materialization of the games. At the same time, I had colleagues who moved in other ways. So, part of what I’m saying is that we also need to be careful not to see the people who appear to be quiet as somehow not radical or somehow not engaged in activism. We’re going to need all of our collective activisms.

Rucker: Right on. I really appreciate that, because what activism looks like for me, Jessica, here in Washington D.C. might look different for a Jessica in Washington State. And that’s very, very real. I’m just scanning the chat right now to see if we have any questions. But as we look at the chat, specifically around this notion of being strategically quiet, I want to go back to the Black people who were not so quiet. You write about how, in 1956 I believe it is, William Faulkner, who’s often taught in secondary U.S. classrooms, he wrote this letter to Life magazine. He’s a Nobel prize winning author and he’s encouraging Black Southerners to wait, or to defer their freedom rights. You use this language of “his comments being steeped in a grammar of time and space.” You talk about time, like this idea of being immediate in space and this idea of integration. I’m curious about how some Black folks in the Civil Rights Movement responded to William Faulkner, and what their response says about the new racial order that the Civil Rights Movement was beginning to establish.

Fleming: So, William Faulkner was that guy. He was the popular white modernist writer, especially throughout the U.S. They still revere him; they have conferences around him. What’s so special about Faulkner is that he actually saw himself as a sort of liberal white person; in many ways, if not a friend of the negro, somebody who at least has a certain intimacy with the negro, who knows the negro. Keep in mind, he writes his article as a response to Brown v. Board of Education, which allegedly led to the desegregation of public schools. In that Supreme Court decision the Court said that you should integrate these schools, and the important phrase was “with all deliberate speed.” For those white Southerners, that set them off, and they set about trying to do it not at all or with all deliberate slowness.

So Faulkner goes to Life magazine to appeal directly to Black people in the South, whom he thinks that he knows, like he’s their boy. He’s like, “Okay, I understand you want freedom. But don’t move too fast. Wait.” He says to them, literally, “Wait. Wait now.” “Wait. Wait now.” So that’s his effort to slow down what he saw Brown unleashing.

Rucker: How do folks respond?

Fleming: Ralph Ellison basically called him a fool. In his letter to Albert Murray, James Baldwin writes a scathing article about William Faulkner. There’s a Black woman playwright whose name is Lola Amis Jones, and she writes a play called The New Ni**er, or, Who’s Afraid of William Faulkner? They see the game that Faulkner is up to, that is Black people and Black artists, and they push back against it.

Rucker: This is beautiful. One, there’s so many different ways to strategically participate in the Black Freedom Movement. Two, Black artists were absolutely critical during this particular era of the 1950s and 1960s, and even today. Especially today. When I was a high school teacher I had an art teacher colleague who believed in art for transformation and art to help raise awareness, to help create access points. So, what I really love about Black Patience is that we can use performance, we can use theater, to help finish the project of emancipation. Before we wrap up, are there any closing thoughts or stories you want to leave us with?

Fleming: I think it’s important for us to know that white supremacy and anti-Blackness are so ingrained in society that it doesn’t need white people to function. When we think about Black patience, it’s easy to think about this as a violent project that only white people engage in toward Black people. But, I want to think about what it meant for President Obama, after Black people were murdered in a church in Charleston, to ask Black people to be patient and to forgive. This happens every time Black people are murdered where they get to the mothers of the victims, and they give them this prepared script to say, “I pray that I don’t want any violence. I forgive the aggressor.” And I get it, but we have to think about where that comes from.

There’s a wonderful clip from Toni Morrison where she talks about Rodney King and the LA riots, and in an interview she said everybody said, “Oh, my God! Those riots were so bad,” and Toni Morrison says, “Oh, my God, I’m surprised they waited for so long.” She said they waited for justice for a year, and it was only when they delivered those not guilty verdicts that they set that city on fire. So, I’ll leave us with this: Black patience is not just a thing from white people; minority people can participate in it as well.

The other thing is that it’s not just a project from the Civil Rights Movement. My parents live in Jackson, Mississippi and they still don’t have clean water. They are still waiting for clean water. We know about Flint, Michigan, right? At the University of Chicago, the trauma center was closed; Black people then had to wait for a long ambulance ride to Northwestern University. In other words, Black patience is still with us, and we still have to be innovative about how we combat it.

Rucker: Thank you. I’m demanding freedom now. Right now. So, Dr. Julius Fleming, Dr. J, I now want to just say thank you, thank you, thank you.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Audiogram

In this audiogram, Julius B. Fleming Jr. discusses Eisenhower’s calls for Black people to be patient in their demands for freedom now — even as he funded the space race and otherwise encouraged transit, media, and finance systems to advance at a rapid pace. Dr. Fleming also emphasizes how Black theater workers were integral to the Civil Rights Movement.

Resources

Many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants.

Lessons and Curricula

|

Poetry of Defiance: How the Enslaved Resisted by Adam Sanchez Teaching SNCC: The Organization at the Heart of the Civil Rights Revolution by Adam Sanchez (Rethinking Schools) Rhythm and Resistance: Teaching Poetry for Social Justice a teaching guide edited by Linda Christensen and Dyan Watson (Rethinking Schools) Sharecroppers Challenge U.S. Apartheid: The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party by Julian Hipkins III, Deborah Menkart, Sara Evers, and Jenice View Freedom Now: The Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi, a lesson by the Choices Program of Brown University |

Books and Plays

|

In addition to Black Patience: Performance, Civil Rights, and the Unfinished Project of Emancipation, the following books were referenced. A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry (Vintage) Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison (Vintage) Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett (Grove Press) Our History Has Always Been Contraband: In Defense of Black Studies edited by Colin Kaepernick, Robin D. G. Kelley, and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor (Haymarket Books) |

Articles and Other Resources

|

Faulkner and Desegregation by James Baldwin Free Southern Theater (SNCC Digital Gateway) An Oral History of the Free Southern Theater by Kristina Kay Robinson and Logan Lockner (Burnaway) Radicals on the Second Line: The Legacy of the Free Southern Theater in the Multicultural South by Elizabeth Rodriguez Fielder Remembering John O’Neal and the Free Southern Theater by Erik Wallenberg (Black Perspectives) |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in People’s History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keywords.

|

April 7, 1712: Revolt by Enslaved Africans in New York Jan. 1, 1863: Emancipation Proclamation March 3, 1865: Freedmen’s Bureau Established Aug. 2, 1924: James Baldwin Born May 19, 1930: Lorraine Hansberry Born March 30, 1952: Charlotta Bass Accepts U.S. VP Nomination Jan. 23, 1963: Patricia Stephens Due Arrested in Florida Aug. 8, 1964: Freedom Schools Convention March 7, 1965: Bloody Sunday March 23, 1965: Selma to Montgomery March Continues April 1, 1965: Blackwell v. Issaquena Board of Education June 30, 1966: Virginia Censorship Board Ceases Operations March 10, 1972: National Black Political Convention May 27, 1972: First African Liberation Day Demonstration on the National Mall |

Participant Reflections

With more than 100 attendees present, the conversation and chat was lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Polls showed participants included 36% K–12 teachers, 28% teacher educators, among many other attendees.

With the 4th annual Teach Truth Day of Action approaching, attendees heard from Pilar Ramos, principal of Arts & Letters 305 United in Brooklyn, on what her school did for the day of action last year:

We learned about banned books, looked up slogans, made posters and pins, and had a book giveaway within the context of our larger spring fair. We focused on the Black Lives Matter at School’s principle of intergenerational learning and thought of ways for all ages to participate in the event. We learned together, were in community together, and had fun together!

They plan to commemorate the day and defend the right to teach truth again this year.

Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

That the idea of using theater as activism has a long history, one that must be studied and replicated today.

I learned that Black cultural workers made a difference in the Civil Rights Movement.

Black patience and this whole idea of waiting, and the role that the arts played in the struggle for freedom.

Black patience and the idea of what it means to be radical. I’m also looking forward to trying to coordinate a Teach Truth Day of Action.

I loved hearing more about the Free Southern Theater.

Virtue being used to keep Black people from demanding freedom now.

I had my eyes opened to the ways Black patience has been exploited. It’s time to stop insisting on patience and hasten this work. The emphasis on storytelling and community is critical to making the progress we need so desperately.

I really appreciated hearing about the K–8 school’s Teach Truth day of action in Brooklyn and how it integrates principles of the Black Lives Matter Movement into their planning and curricula.

What will you do with what you learned?

I’m planning to create a unit for my language arts classroom where we will do a critical reading of parts (or all) of Kicks & Co. This will open the door for many larger, more necessary conversations.

Make connections throughout history and today of oppressed people being told to wait.

I’m going to take it to the students and offer them a platform to discuss the historical forms of patience, and how patience and waiting relates to them today.

I intend to purchase Julius Fleming’s book and work with the Creative Writing, African American History, Debate, and Drama teachers to incorporate and expand on elements and themes in the text.

I will continue to incorporate these messages into my lessons where students are critically examining and questioning our society and world. I want them to make the connections as we study Weeksville in Brooklyn to the present day Black Lives Matter movement and beyond.

Not only share the information with my students, but my family and friends too.

I will ensure that I’m teaching in a way that fosters criticality. It’s not enough to expose students to these powerful pieces, I have to be intentional about seeing that they walk away understanding that they are radical pieces of art.

I will be using this content in my AP African American Studies class next year.

I will be thinking about how to include this in my higher ed engineering classes. I am a community organizer and activist and will definitely be bringing this discussion to some of our political ed discussions. I will also share this with my public school teacher friends and hope they start the conversation in their classrooms.

Presenters

Julius B. Fleming Jr. is associate professor of English at the University of Maryland. Specializing in Afro-Diasporic literatures and cultures, he has particular interests in performance studies, Black political culture, diaspora, and colonialism, especially where they intersect with race, gender, and sexuality. He is the author of Black Patience: Performance, Civil Rights, and the Unfinished Project of Emancipation.

Jessica Rucker is a graduate student in the Department of American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park, and a Prentiss Charney Fellow. Prior to her graduate work, she was a high school teacher in Washington, D.C.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn