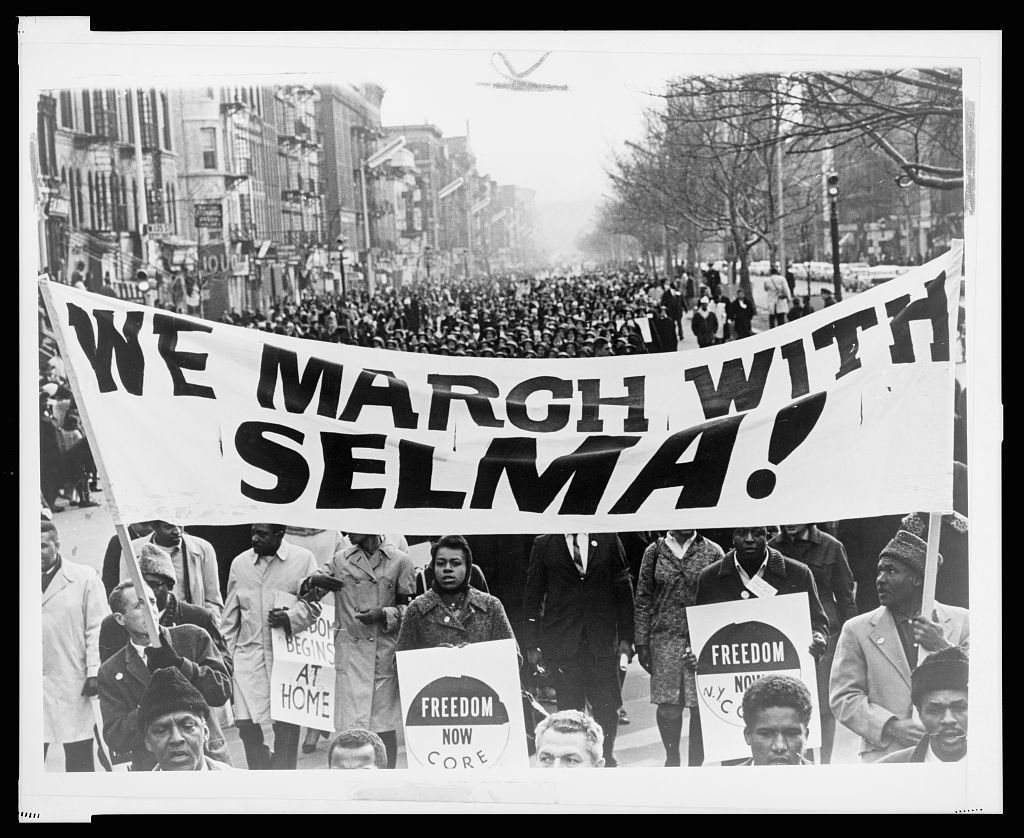

After the police murdered Jimmie Lee Jackson, 600 people began a march on March 7, 1965 from Selma to Montgomery to confront Governor Wallace about the lack of justice served for the officer who committed the crime, and to protest the violation of their constitutional rights to vote. The march was organized by Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and the Dallas County Voters League.

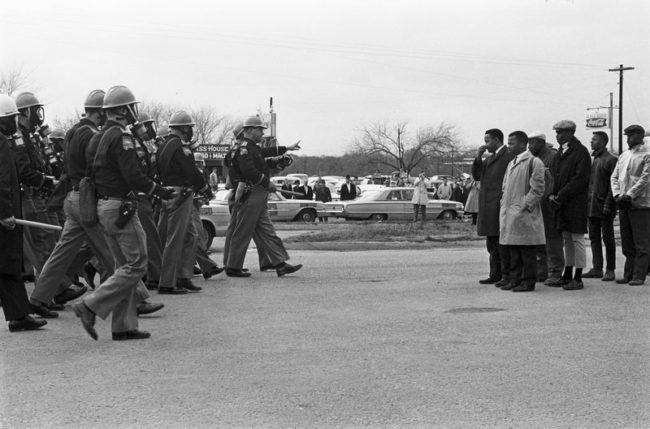

Spider Martin’s best known photograph, “Two Minute Warning,” shows marchers facing a line of state troopers in Selma moments before police beat the protesters on March 7, 1965. The day became known as Bloody Sunday.

All went according to plan until they reached the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where they met extreme violence from a wall of Alabama state troopers, who had been waiting for them. The march was halted as the troopers and sheriff’s tear-gassed and beat marchers.

In Ten Things You Should Know About Selma Before You See the Film, Emilye Crosby explains:

Although many people are aware of the violent attacks during Bloody Sunday, white repression in Selma was systematic and long-standing. Selma was home to Sheriff Jim Clark, a violent racist, and one of Alabama’s strongest white Citizens’ Councils — made up of the community’s white elite and dedicated to preserving white supremacy. The threat of violence was so strong that most African Americans were afraid to attend a mass meeting.

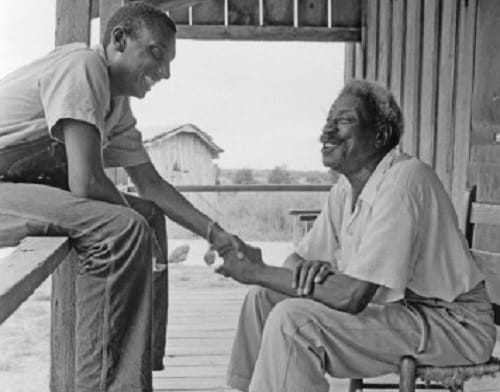

Most of SNCC organizers Colia (Liddell) and Bernard Lafayette‘s first recruits were high school students. Too young to vote, they canvassed and taught classes to adults. Prathia Hall remembers the danger in Alabama:

…[I]n Gadsden, the police used cattle prods on the torn feet [of young protesters] and stuck the prods into the groins of boys. Selma was just brutal. Civil rights workers came into town under the cover of darkness.

Even with the work of SNCC and the Dallas County Voters League, it was almost impossible for African Americans to register to vote. The registrar’s office was only open twice a month and potential applicants were routinely and arbitrarily rejected. Some were physically attacked and others fired from their jobs.

Howard Zinn, who visited Selma in the fall of 1963 as a SNCC advisor, offers a glimpse of the repression, noting that white officials had fired teachers for trying to register and regularly arrested SNCC workers, sometimes beating them in jail. In one instance, a police officer knocked a 19-year-old girl unconscious and brutalized her with a cattle prod. Read more in Ten Things You Should Know About Selma Before You See the Film.

Find lessons and other resources below to teach about the history of organizing in Selma, SNCC, voting rights, and police brutality. Be sure to include the role of Marcus Garvey’s UNIA with sharecroppers in the region, laying the groundwork for the formation of the DCVL and later SNCC.

“One More Bridge to Cross” is a song composed by Joe DeFilippo and performed by the R. J. Phillips Band, a group of Baltimore musicians. Listen here.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn