By Bill Bigelow

This article was originally published in Teaching When the World Is on Fire.

Portland, Oregon, where I have lived and worked for more than forty years, has a reputation as a progressive and environmentally conscious city. So imagine teachers’ surprise when we learned in 2007 that the school district had purchased a textbook, McDougal Littell’s Modern World History, which relegated discussion of climate change to three miserable paragraphs buried on page 679. “Not all scientists agree with the theory of the greenhouse effect,” it read, and went on to blame poor countries for dragging their heels on climate solutions while wealthy countries were leading the way.1 The book failed to include a single quote from anyone touched by climate change. And this was the text to be used in modern world history classes, taken by almost all students in Portland high schools.

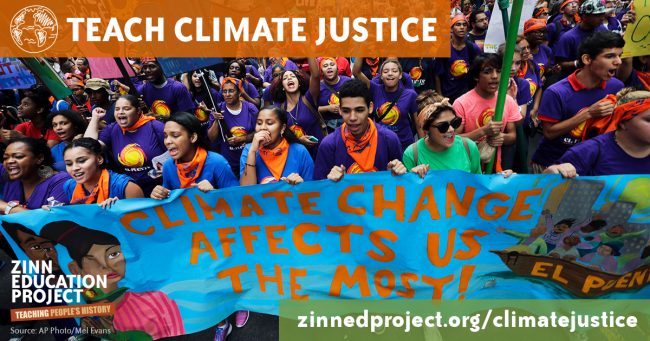

Social studies teachers in Portland have long been a feisty lot, and many simply ignored this district-adopted textbook or used it for target practice to engage students in “talkback” reading activities looking at whose perspectives the book ignored or distorted. But in the fall of 2015, teachers, parents, students, and climate justice activists began meeting to chart a different response to the failure of the school district to deal forthrightly with what is arguably the most serious crisis facing humanity.

My colleague Tim Swinehart and I had worked for years to produce a comprehensive resource for teachers — a book of role plays, simulations, and student-friendly readings, A People’s Curriculum for the Earth: Teaching About the Environmental Crisis (Rethinking Schools), published earlier that year. 350PDX, the local affiliate of the global climate justice organization, 350.org, invited us to lead a workshop based on the book to involve educators and climate activists in exploring ways that we could work together to get the school district to take more affirmative action on the climate crisis.

My colleague Tim Swinehart and I had worked for years to produce a comprehensive resource for teachers — a book of role plays, simulations, and student-friendly readings, A People’s Curriculum for the Earth: Teaching About the Environmental Crisis (Rethinking Schools), published earlier that year. 350PDX, the local affiliate of the global climate justice organization, 350.org, invited us to lead a workshop based on the book to involve educators and climate activists in exploring ways that we could work together to get the school district to take more affirmative action on the climate crisis.

Urged on by environmental justice activists, Portland’s city council had recently passed a resolution banning new fossil fuel infrastructure in the city. In the glow of this bold move, the teachers and activists at the 350PDX workshop that Tim and I led hatched the idea of working on a climate justice resolution to bring to the school board. We wanted board members to commit the school district to abandon the use of textbooks that minimized the severity of the climate crisis or its social roots, and to take a more robust approach to climate justice professional development and curriculum sharing.

Teachers weren’t the only ones demanding change. Students at one Portland high school, similarly disgusted by the Modern World History textbook, demanded a meeting with the assistant superintendent in charge of teaching and learning to express their grievances about this book, and to demand alternatives. They knew the book lots better than he did, and in their meeting, peppered him with example after indefensible example of passages that have no place in a public school classroom.

We began to collaborate. Our group of teachers, students, parents, and climate activists gave ourselves a name — Educating for Climate Justice — and over several months of evening meetings, we crafted a resolution to bring to the school board. The process of agreeing on language for the resolution was time-consuming but exhilarating. It was one thing to know that we wanted the school district to scrap wretched textbooks like Modern World History, but more difficult to articulate precisely what we wanted instead.

We were startled by how many people assumed that we were drafting a resolution aimed simply at greater inclusion of “climate literacy” in science classes. No doubt, that was one aspect of our work. But committee members saw this as a social issue, not strictly a scientific one. As Naomi Klein emphasized in the subtitle of her book This Changes Everything, the root of the crisis lies in how wealth and power are structured in our society; it’s capitalism versus the climate. Thus in our resolution, we emphasized that “it is essential that in their classes and other school activities students probe the causes and consequences of the climate crisis . . .” and explore “potential solutions that address the root causes of the crisis.”2 This put justice at the heart of our work, not carbon dioxide.

We intended the resolution to acknowledge the effects of climate change as a local issue, that these effects are felt not only far away in the Arctic or sub-Saharan Africa. However, we wanted to balance the local with the global. Nothing is more central to the climate crisis than inequality. And it is inequality that is the common denominator, whether we are talking about climate impacts here in Portland next to the Columbia River, or half a world away in Bangladesh next to the Brahmaputra River. As the resolution indicated, a climate justice curriculum should seek to center the lives and experiences “of people from ‘frontline’ communities, which have been the first and hardest hit by climate change.” For years, Portland Public Schools has focused on equity. Well, climate change is the mother of all equity issues, as the people least responsible for this planet-threatening crisis are the first to suffer, and the ones most responsible for causing it are the best positioned to insulate themselves from its worst effects.

Too often, when school districts decide on new curricular initiatives, they operate from a consumer paradigm: commence the hunt for different programs or texts to purchase, and then impose these on teachers. Instead, we saw the school district’s climate justice work as a grassroots, collective project of people throughout the school system: professional development and curriculum materials would be fashioned “in ways that are participatory, imaginative, and respectful of students’ and teachers’ creativity and eagerness to be part of addressing global problems, and that build a sense of personal efficacy and empowerment.”

Last but not least, we insisted that student activism is the necessary response to the immense threat of the climate crisis: “All Portland Public Schools students should develop confidence and passion when it comes to making a positive difference in society, and come to see themselves as activists and leaders for social and environmental justice . . . ; and it is vital that students reflect on local impacts of the climate crisis, and recognize how their own communities and lives are implicated.”

Our resolution was expansive and ambitious, but right-wing media throughout the country would focus their outrage on the resolution’s final sentence: “[Portland Public Schools] will abandon the use of any adopted text material that is found to express doubt about the severity of the climate crisis or its root in human activities.” More on that in a moment.

As Educating for Climate Justice closed in on a final draft, we began to reach out to community groups to enlist their endorsement, and ultimately signed on more than thirty organizations, including Oregon Physicians for Social Responsibility, the Sierra Club, the Portland Association of Teachers (the teachers union), Climate Jobs PDX, Rising Tide, the Climate Action Coalition, the Raging Grannies, several synagogues, and of course, 350PDX.3

In May 2016, members of our committee and community supporters — many of us dressed in Portland’s climate justice red — gathered for a short but spirited rally at the high school where the school board was meeting. Prior to our testimony in support of our resolution, we were introduced by board member Mike Rosen, who had supported our work from the beginning and was our liaison with the school board. Six of us testified before the school board, including Gabrielle Lemieux, a student who had helped craft our resolution from the very beginning. The week before the board meeting, many in our committee had traveled to a “Keep It in the Ground” demonstration in Anacortes, Washington, home to two oil refineries. Part of the demonstration was a blockade of railroad tracks into the oil refineries. Gaby testified:

People said to me, “You have a whole lifetime ahead of you to get arrested, to do this kind of work.”

My response is: We don’t have my lifetime to wait. We don’t even have the couple years it will be before I’m truly an adult. My action starts now, or it works never. Your action, this action, accepting this resolution and taking on the responsibility as educators to create an effective, engaging, and comprehensive climate curriculum that starts now. It must start now.

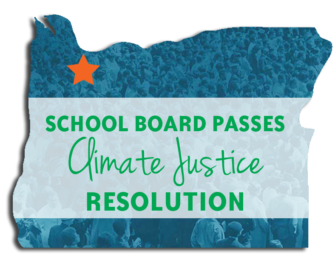

The school board, a seven-member body elected citywide, voted unanimously to support our resolution.

The school board, a seven-member body elected citywide, voted unanimously to support our resolution.

Our post-resolution glee was short lived. The next day, a headline in the Portland Tribune shouted, “Portland School Board Bans Climate-Change Denying Materials.” The school board’s resolution never mentioned the word “ban,” but we should have been prepared for what the L.A. Times called the “firestorm” of right-wing media vitriol that ensued. The Tribune article generated 3,152 online comments, calling us “latter day inquisitors” and worse, and drew the attention of Fox News, the Washington Times, the National Review, Glenn Beck’s The Blaze, the Heartland Institute, and others. All joined the chorus to denounce censorship and book banning, with some outlets painting us as book burners. An Accuracy in Media article, “The Red Guards Are Green,” quoted Patrick Wood, editor of Technocracy News & Trends: “Will they ban materials from the homes of students? What will be the punishment for being caught with such materials on Portland Public School campuses?” Portland’s most widely read newspaper, the Oregonian, accused us of “indoctrination.”

But there were also welcome gestures of solidarity, like the organization Climate Parents, which collected more than a thousand signatures thanking Portland’s school board for passing the resolution.4

The storm of controversy caught us off-guard and for a few weeks distracted us from the work of beginning to implement the resolution. But over the summer, as “banning” accusations waned, we met with school district officials and established ourselves as a formal school district committee, the Portland Public Schools Climate Justice Committee.

Frontline Communities

Our committee never made a conscious decision to postpone our evaluation of Portland textbooks, but given the storm of controversy, we decided to let those winds die down and return to the problem of biased textbooks later in the year.

Pushing the school district to take climate justice seriously meant that we could not just proceed sequentially.

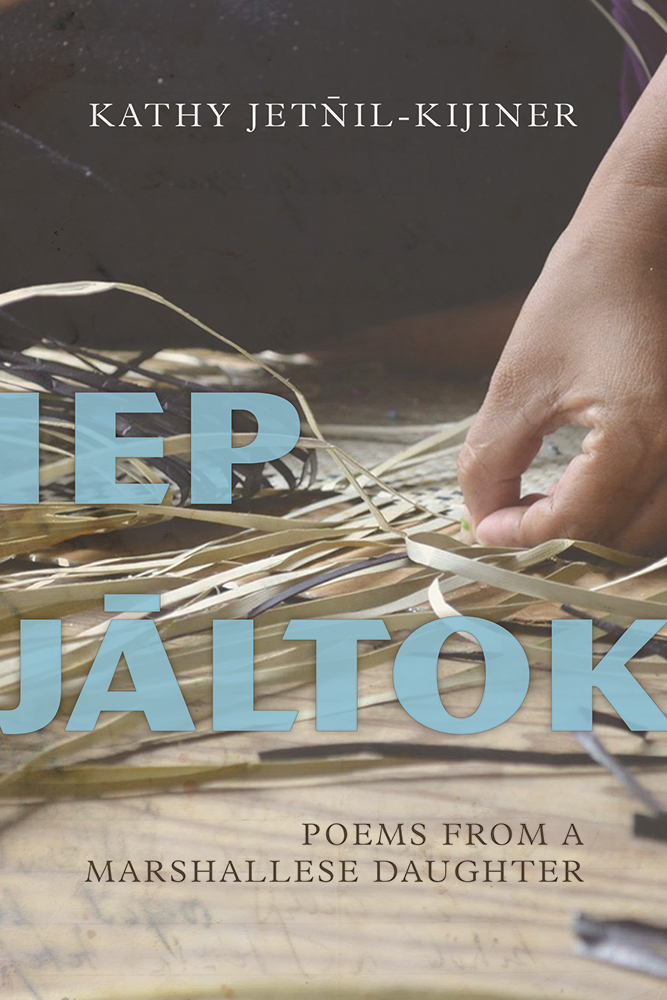

We were fortunate that our committee launched just as the Marshall Islands performance poet Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner arrived in Portland to live here part of the year. Kathy’s poem, “Dear Matafele Peinam” — written to her seven-month-old daughter to open the 2014 United Nations climate talks in New York — had begun to work its way into the curriculum of some Portland teachers, and her work exemplified our commitment to center the lives and voices of people from frontline communities in our curriculum work. The poem, which Kathy performs from memory, “poetry slam” style, captures the existential threat of the climate crisis:

dear matafele peinam,

i want to tell you about that lagoon

that lucid, sleepy lagoon lounging against the sunrise men say that one day

that lagoon will devour you

they say it will gnaw at the shoreline

chew at the roots of your breadfruit trees

gulp down rows of your seawalls

and crunch your island’s shattered bones

they say you, your daughter

and your granddaughter, too

will wander rootless

with only a passport to call home

But moves toward hope:

still

there are those who see us

hands reaching out

fists raising up

banners unfurling

megaphones booming

and we are

canoes blocking coal ships

we are

the radiance of solar villages

we are

the rich clean soil of the farmer’s past

we are

petitions blooming from teenage fingertips

we are

families biking, recycling, reusing,

engineers dreaming, designing, building,

artists painting, dancing, writing

and we are spreading the word . . .

The Marshalls, located about halfway between Hawaii and Australia, rise no higher than six feet above sea level. As Kathy offers simply in her poem, “Tell Them”: “We only have one road.”

We contracted with Kathy for professional development with teachers, and sessions in Portland middle and high schools. Performance poetry is well suited to describe and denounce climate change. It is personal, story-rich, angry, and accessible. Kathy’s poetry is a cri de coeur that offers a glimpse into the enormity of a crisis that is drowning homes and cultures. And, as we would soon see, it is a form of creative expression that invites students to share their own lives, and to name the hurt and injustice closer to home about gentrification, police violence, proposed liquefied-natural-gas pipelines, and more.

We contracted with Kathy for professional development with teachers, and sessions in Portland middle and high schools. Performance poetry is well suited to describe and denounce climate change. It is personal, story-rich, angry, and accessible. Kathy’s poetry is a cri de coeur that offers a glimpse into the enormity of a crisis that is drowning homes and cultures. And, as we would soon see, it is a form of creative expression that invites students to share their own lives, and to name the hurt and injustice closer to home about gentrification, police violence, proposed liquefied-natural-gas pipelines, and more.

We soon recognized that if we were serious about honoring the resolution’s call to center the voices of people from frontline communities, those voices didn’t focus only on climate change. In Kathy’s work, the climate crisis was embedded in a historic web of colonial domination — the Marshalls were colonized first by the Germans, then Japanese, then Americans — and were literally ground zero for a decade of nuclear tests in the 1940s and 1950s that vaporized entire islands, and especially victimized women through radioactive pollution.

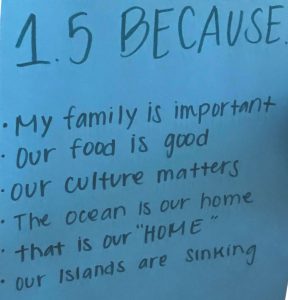

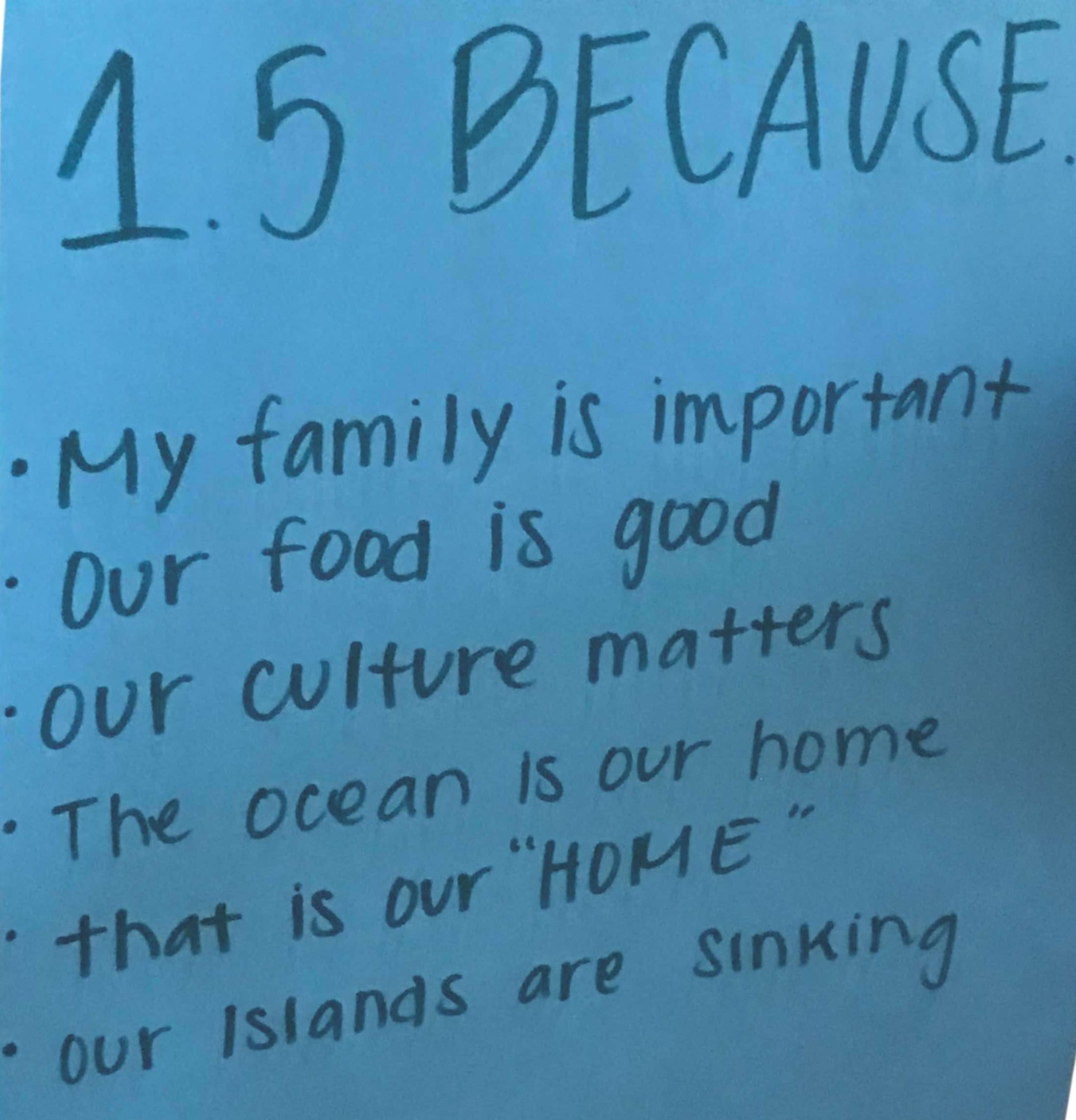

Starting in the fall of 2016, Kathy has led three professional development sessions for a couple hundred Portland educators, and thirty-three workshops for about two thousand students from six high schools and two middle schools. Some of these have been exclusively for Pacific Islander students, arguably one of the least-served student populations in our school district. These focused on climate issues, but also on racism, linguistic discrimination, and PI students’ struggles to make a home in an overwhelmingly white city, with a legacy of racism hammered into its foundation. But these sessions with students from Fiji, Chuuk, Palau, American Samoa, Hawaii, the Ryuku Islands, Western Samoa, and Tonga were also joyful occasions of people finding community in institutions that at times make Pacific Islanders feel invisible. These workshops highlighted the intersection between climate justice education and ethnic studies: When the students gather, they articulate not only concerns about climate change but also about the curricular silence about their cultures, and other indigenous issues. As one young woman shared, “The only time they talk about Hawaii is when they mention Pearl Harbor.”

Choking back tears at a school board meeting, Roosevelt High School twelfth-grade student Siale Ita, whose family is from Tonga, spoke of how moving it was to work with Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner: “As a young Pacific Islander woman, I have never in classrooms — sorry, it just gets me so emotional. I have never learned about climate change in any of my classrooms — science, history, and the effects it has on the Pacific Islands. My people are having to evacuate their homes.”

Students in Roosevelt High school’s Pacific Island Club used poetry to refocus the narrative surrounding climate justice onto frontline communities. Read more.

Siale performed a poem in front of the school board inspired by Kathy’s work that tracks the climate-changed ocean, inching higher on her island:

The water rising to her ankles,

She remembers those nights waking up to her home flooded yet again,

Learning there is nowhere on this island to escape the floods

The next morning she makes her daily offerings

into the ocean, whispering,

“Are you a friend or a foe?

Please spare us some more time.

I’ll climb to the highest peak with my people on my back

if that is what it takes to find peace.”

As Siale’s poem progresses, the water rises to the woman’s knees, her hips, her breasts, her shoulders, and finally to her head:

She is ready to surrender unto the sea.

Yet she hears the chants of her people from afar, screaming,

“We will not go, we will stay.

We will plant our feet into the earth.”

She too will plant her feet into the earth.

She is staying on this island.

Professional Development

I began teaching in Portland in 1978. One of the persistent struggles that teachers face has focused on the question: who owns the curriculum? In the 1990s, Portland hired a new superintendent who was fond of telling people that nothing had been done in the way of curriculum in Portland. She was referring to the fact that Portland did not have a standardized curriculum with common assessments, instituted and closely monitored from the top. So even though Portland was home to a rich culture of curriculum development — quarterly teachers-teaching-teachers curriculum days; the Oregon Writing Project, one of the most vital sites in the National Writing Project network; and years of grassroots curriculum writing and sharing — to many administrators, all this added up to a big nothing.

As for the PPS Climate Justice Committee, we were concerned that once passed, our school board resolution might be buried in a central office file cabinet. But another concern was that the district would contract with an outfit to “deliver” professional development to teachers. As mentioned, the resolution proposes a very different curriculum development model, one that is “participatory” and “imaginative.” One of our committee’s first district-wide gatherings asked teachers to come together to imagine what climate justice looks like at their grade level and in their discipline. We were excited to have diverse teacher participants from early elementary, middle school Spanish, high school science, and lots in between.

In December 2014, 20 teachers joined Bigelow for a Zinn Education Project/This Changes Everything writing retreat weekend near Portland.

In our first gathering, Rachel Hanes, a second-grade teacher and committee member, pointed out that the environmental standard at her grade level called for children to learn that plants need water and sunlight to grow. The prescribed experiment is to grow a sunflower and discuss how a sunflower might fare in different environments like a desert or the Arctic.

There is nothing wrong with this sliver of knowledge, but as Rachel pointed out, this unambitious objective imagines that her students are much less capable than they are. She shared a profound “Storyline” curriculum she developed with colleagues at her school in which students construct a town and then are challenged to solve problems as a community. One of these is to respond to a proposal from the “Carson Environmental Oil Co.” to “take part in an exciting new opportunity to create jobs and earn money for our city by allowing them to put a pipeline through the community. Although some trees will be cut down and some residents may need to be relocated, but they will be compensated!” The debates and learning that ensue are rich and intense, and Rachel shared with us her students’ conversations about solidarity: What happens if our community rejects the pipeline and Carson decides to move it to a different community? As Rachel explained, “I want my students to see themselves not as hopeless victims in the struggle for climate justice but as actors who can have an impact on the world around them.” Second graders.

In 2019, a math educator brought data from a friend’s solar panels into her 7th-grade classroom to build a bridge between math and climate justice education. Learn more.

As a career high-school social studies teacher, I was inspired to see what it looks like for second graders to take a critical look at the fossil fuel industry, and for third graders to represent people from around the world in a climate justice forum and express how they are affected by climate change. And as someone who almost flunked my own high school chemistry class, seeing how science can — and should — intersect seamlessly with social studies and other disciplines was a revelation. If only my own 1968 chemistry class had been so socially aware!

In subsequent meetings with some school district officials to discuss implementing the climate justice resolution in Portland schools, they have tried to figure out “where it goes” in the curriculum, as if there is a discrete “it” to be slotted into a particular discipline and grade level. Too often, climate change has been a curricular hot potato, with no one claiming it as theirs. However, as our teacher curriculum gatherings showed, climate justice work in schools “belongs” to all of us, and we can be inspired by one another’s work.

Climate Warriors

In an audacious embrace of Portland’s climate justice resolution, teachers in Madison High School’s Citizen Chemistry for All course — a class enrolling more than three hundred sophomores in the school — adopted an essential question for the year: “Why are human changes to Earth’s carbon cycles at the heart of climate destabilization?” Students would demonstrate their learning at a two-day Climate Justice Fair in Madison’s library, in which they would represent “communities which are engaging as ‘climate warriors,’ providing critical analysis of their work and or proposing additional needed activism.”

Rose High Bear (Deg Hit’an Dine), producer of the NPR series Wisdom of the Elders, and featured Bigelow’s article, “Students ‘Warrior Up’ For Climate Justice.”

An honest, rigorous look at the science of climate change can be terrifying and disheartening. Falling into cynicism is a hazard one confronts simply by living in our society, with its inequality, violence, and lack of democracy. But add to that, knowledge of the inexorable rise of greenhouse gases in our atmosphere — and what this heat-trapping pollution means for the Earth — and despair feels like more than a threat, it feels like common sense. Knowing this, Madison teachers focused not purely on the science of climate destabilization, but also on the people who are taking action to reverse it, inviting students to research “Climate Warriors,” those who have not given up, those who “know the truth,” and yet are not defeated by it.

For the project, students had three areas of work they had to complete: Direct Action, Climate Justice Warrior Storytelling, and Listening and Reflecting at the Climate Fair. Direct actions could include simply writing a letter, designing a poster, or taking a stand in some way, but could also include making a short film, participating in a rally or hearing, or making a personal or family lifestyle change that could contribute to mitigating climate destabilization. Madison chemistry teachers — which included Rachel Stagner, also a member of our PPS Climate Justice Committee, and Tim Kniser — required students to identify one of the climate-related crises or issues explored in class and to create a slideshow, poster, short film, podcast, or some other way to “show how a ‘climate warrior’ is fighting against this issue.”

And at the fair, students were expected to offer feedback to at least four other presenters. I attended the first day of the fair. The library buzzed with anticipation. Treothe Bullock, a science and language arts teacher, launched the day with the invitation: “There isn’t anyone who has the answer. We’re figuring it out.” Every student received a “Climate Justice Passport” to take notes in. Students had to identify the climate warrior, the issue they are involved in, the chemistry connection, and to evaluate the proposed solution.

Students’ “warriors” were diverse and included Xiuhtexcatl Martinez, a plaintiff in the landmark Our Children’s Trust lawsuit, Juliana v. United States of America; Nobel Peace Prize-winner and former president of Ireland Mary Robinson, who works especially on the intersection of climate change and women’s issues; Rose High Bear (Deg Hit’an Dine), producer of the NPR series Wisdom of the Elders; West Virginia mountaintop-removal activist Maria Gunnoe; Crystal Lameman, of Canada’s Beaver Lake Cree Nation, featured in the film This Changes Everything; and Zack Rago, a reef aquarist and scuba diver who appears in the film Chasing Coral. The young woman presenting Rago as her “climate warrior” taught me more about coral during her short presentation than I’d ever known. (Did you know that coral is simultaneously rock, plant, and animal?)

Other students chose organizations or movements as their warriors rather than individuals. One student focused on 350.org, especially their “Keep It in the Ground” campaign — “They really want you and me to get involved in this.” A couple students presented the indigenous movement to oppose the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL). About the pipeline’s builders, Energy Transfer Partners, one student presenter commented: “There is not much depth to what they want. They just want more.” And one student, clearly moved by her research, described her personal commitment to abandon eating meat because of cattle’s out-sized carbon footprint.

The New York Times featured environmental justice students at Lincoln High School in Portland, Ore., (three pictured above, with their teacher on the far right) in Spring 2019. Source: Amanda Lucier.

Despair is always a step away when we begin looking deeply at the contours of our climate emergency. But in Madison’s Climate Justice Warrior project students encountered the hope and determination of activists alongside the disturbing science of climate change. And as dire as the news can appear, our curriculum needn’t be similarly grim. During the Climate Justice Fair, the Madison library was electric with laughter — students telling stories, others listening respectfully, blurting out the frequent “wow” and “I never knew that.”

Textbooks: The Bad and the Ugly

Textbooks: The Bad and the Ugly

In the testimony I gave to the school board in 2016 arguing for our climate justice resolution, I focused on two adopted textbooks, still currently in use, to highlight the need for alternative curriculum. I mentioned earlier the terrible Modern World History, but as egregious in its own way was a Pearson/Prentice Hall text, Physical Science: Concepts in Action, which finally gets around to mentioning climate change on page 782. The few paragraphs on the human source of a warming planet are soaked in doubt: “Human activities may also change climate over time. One possible climate change is caused by the addition of carbon dioxide and certain other gases into the atmosphere.” The text shrugs off the certainty of human-caused climate change with a timid vocabulary of “possible,” “might,” “could,” and “may”: “Carbon dioxide emissions from motor vehicles, power plants, and other sources may contribute to global warming” — a nothing-to-worry-about line that would be right at home in Koch brothers propaganda.5

So we knew that Portland schools used at least two problematic texts, but in spring 2017, our committee developed a rubric to evaluate all school district-adopted science and social studies textbooks — not just “environmental studies” texts — for their compliance with the school board’s resolution. Criteria included:

- The text provides stories and examples that help students grasp the immediacy, systemic nature, and gravity of the climate crisis.

- The text includes actions that people are taking to address the climate crisis, locally and worldwide.

- The text emphasizes that all people are being affected by the climate crisis, but also highlights the inequitable effects of the crisis on certain groups (e.g., indigenous peoples, people in poverty, Pacific Islanders, people in sub-Saharan Africa, people dependent on glaciers for drinking water and irrigation, etc.).

- The text does not use conditional language that expresses doubt about the climate crisis (e.g., “Some scientists believe . . . ,” “Human activities may change climate”).

- There are discussion and/or writing questions that provoke critical thinking.

Our committee invited individuals from our partner groups for a full-afternoon evaluation session and thirteen of us gathered at the school district administration building with fifteen adopted science and social studies textbooks to assess whether all were as problematic as the ones we had previously critiqued. Our conclusion: every adopted textbook was out of compliance with the school board’s resolution.

Read more about textbook misinformation in Bigelow’s article, Teaching the Truth About Climate Change Is Up to Us, Because Textbooks Lie. Illustration by Michael Duffy.

Not surprisingly, all the books ignored or dramatically minimized the severity of the climate crisis. The high school economics textbook, Contemporary Economics, says nothing about climate change in more than 700 pages. An adopted U.S. history text, Pursuing American Ideals, includes one sentence on climate change in 890 pages. The high school text Biology includes three paragraphs in its 1,100 pages. And on and on.

Reviewers also found lots of missed opportunities. The eighth-grade adoption, History Alive!: The United States Through Industrialization, contains less than a paragraph relating to climate change in 505 pages. One PPS reviewer commented, “While this book goes only through industrialization, the book fails to alert students to the practices and ideology that will ultimately lead us to the climate crisis. These days a history text should do that.” Another reviewer commented about Magruder’s iconic American Government: “How can a book about the U.S. government say nothing about the climate crisis — or environmental policy more broadly? This is egregious, unacceptable.” About the high school AP European history textbook Western Civilizations, one reviewer noted that the book talks about the pollution that came with the industrial revolution, but here, too, fails to bring this up to the climate crisis. The book contains one sentence on global warming out of its 1,063 pages. American Spirit Reader, an AP/IB high school U.S. history adoption, includes nothing in its 538 pages relating to climate change. One reviewer noted, “As with other books on U.S. history, there is an opportunity to look at early U.S. history as the prologue to the climate crisis, but this book is utterly silent.”

To the extent that district-adopted textbooks discuss climate change, no text suggests that students or ordinary people might play a role in addressing this growing threat — or that “frontline communities” are themselves responding to the climate crisis. In its one sentence on climate change, History Alive! Pursuing American Ideals says that “environmentalists fear” problems like global warming.6 Indeed. But the climate justice resolution’s intent is to underscore our students’ own role in making the world a better place, rather than assigning concern and action only to scientists or environmentalists.

I suppose that none of this comes as a surprise. The giant corporations that produce these textbooks have no interest in students asking critical questions about the economic system that regards profit maximization as the highest aim. These corporations are themselves richly rewarded by a profit-first economy, so are unlikely to suggest that this economic system may be at the root of our environmental crisis. And, of course, multinational textbook publishers seek markets in states dominated by fossil fuel interests, and thus are reluctant to suggest that continuing to burn fossil fuels jeopardizes nature and humanity.

Nonetheless, our committee is preparing letters of “noncompliance” with the Portland Public Schools climate justice resolution to send to textbook publishers, cataloging how their textbooks fail to address climate issues in even mildly satisfactory ways. We are also sending letters to district middle school, science, and social studies teachers alerting them to our findings, and urging them to seek alternatives to these problematic resources.

Activists and Leaders

Here’s the feature of the climate justice resolution that committee members probably invoke most often: “All Portland Public Schools students should develop confidence and passion when it comes to making a positive difference in society, and come to see themselves as activists and leaders for social and environmental justice.” We especially want educators to know that it is the official policy of the school district that we should nurture students’ activist sensibilities. And this is surely what our right-wing critics were most exercised about when they learned that the school board had passed this resolution — that school district leaders imagined schools as sites for activism.

There is no road map for how we can make sure that schools play a central role in addressing our climate emergency. Not only do commercially produced textbooks not have an answer to responding to the climate crisis, they are solidly part of the problem. The school board passed a magnificent resolution, but top administrators have offered tepid support for climate justice education and appear to remain attached to a model of teaching and learning that embraces “power standards” and programs developed at great distance from classrooms to be imposed on teachers.

At a recent, cross-border teaching for social justice conference sponsored by the Surrey Teachers’ Association and the British Columbia Teachers’ Federation, keynote speaker Naomi Klein lamented that although our “leaders” occasionally pay lip service to the climate emergency, they act like everything is normal. Sadly, the same is true in our schools. At the level of school leadership, there is no sense of crisis, of urgency. This is the work that educators are called to.

In fact, we could have accomplished much of our climate justice work in Portland without an official school-board resolution. If there is something to be learned from our experience here it’s that people of conscience need to find one another and begin to act. History teaches that anything good and decent and just we have in our society is because people organized to effect change. It’s a lesson those of us connected to school communities need to take to heart. Our house is on fire. Let’s act like it.

Notes

1. Roger B. Beck, et al., eds., Modern World History: Patterns of Interaction (McDougal Littell, 2007).

2. “Resolution No. 5272: Resolution to Develop an Implementation Plan for Climate Literacy,” Portland Public Schools Board of Education, passed May 17, 2016.

3. Not every group we approached decided to endorse our campaign. Despite including language in the resolution, at the urging of the statewide AFL-CIO, about making students aware of “living wage jobs in the just transition away from fossil fuels,” the AFL-CIO did not endorse the resolution — reflecting the tensions in a number of labor unions in the federation about joining the movement to abandon a fossil fuel-based economy.

4. “Portland School Board Bans Climate Change-Denying Materials,” by Shasta Kearns Moore, Portland Tribune, May 19, 2016; “Portland Public Schools Ban Textbooks That Cast Doubt on Climate Change,” Fox News, May 22, 2016; “Fox Hosts Upset That Portland Schools Will Stop Teaching Climate Denial to Children,” Media Matters for America, May 22, 2016; “Portland Public Schools Board Bans Any Dissent from Climate Dogma,” Jim Lakely, The Heartland Institute, May 22, 2016; “The Portland School Board’s Climate-Change Meltdown,” Editorial, The Oregonian, May 26, 2016; Fox News Channel — “Your World with Neil Cavuto” — Monday May 30, 2016, selected excerpts; “The Red Guards Are Green,” by Cliff Kincaid, Accuracy in Media, June 6, 2016.

5. Michael Wysession, David Frank, Sophia Yancopoulos, eds., Physical Science: Concepts in Action (Boston: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006).

6. Diane Hart, History Alive!: Pursuing American Ideals, student edition (Teachers Curriculum Inst, June 30, 2008).

Bill Bigelow is curriculum editor of Rethinking Schools magazine and co-director of the Zinn Education Project. He is the author or co-editor of many Rethinking Schools publications, including A People’s History for the Classroom, The Line Between Us: Teaching About the Border and Mexican Immigration, Rethinking Globalization: Teaching for Justice in an Unjust World, Rethinking Our Classrooms–Volumes 1 and 2, Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years, and A People’s Curriculum for the Earth: Teaching Climate Change and the Environmental Crisis. Bigelow lives in Portland, Oregon, and has taught high school social studies since 1978.

This article was originally published in Lisa Delpit’s book, Teaching When the World Is on Fire (The New Press, 2019) and is reprinted here with permission of The New Press.

This article was originally published in Lisa Delpit’s book, Teaching When the World Is on Fire (The New Press, 2019) and is reprinted here with permission of The New Press.

Bigelow is one of several educators from the Zinn Education Project’s two co-coordinating organizations who contributed to the collection. Other contributors from Rethinking Schools were Wayne Au, Camila Arze Torres Goitia, Jesse Hagopian, Stan Karp, and Natalie Labossiere. The book also includes an essay from Allyson Criner Brown, associate director at Teaching for Change. Find out how to receive a free copy.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn