On Teaching People’s History

By Judy Richardson

Judy Richardson. By Rick Reinhard, 2011.

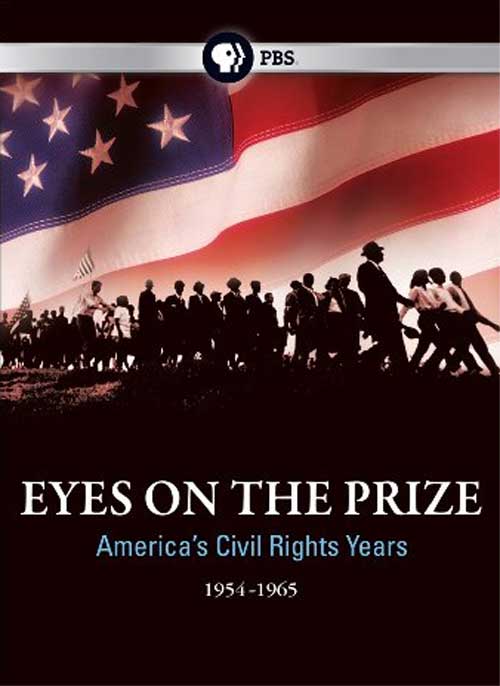

Back in 1978, when we first started production on what later became the 14-hour Eyes on the Prize series, everything — films, books, curricula — evolved around Dr. King. Times have changed somewhat, but not as much as I would have assumed. The wonderful new local movement scholarship that has examined activism in southern communities big and small somehow hasn’t “trickled down” beyond the upper reaches of academia the way it rightfully should have.

The problem with this singular focus on Dr. King isn’t just that it’s ahistorical. Even more insidious, by focusing only on the greatness of Dr. King, we ignore the amazing courage, strength and brilliant leadership of regular folks, particularly Black folks in the Deep South like Fannie Lou Hamer, Hartman Turnbow, Fred Shuttlesworth, Harry and Harriette Moore (and we should never forget one of the Movement’s foremost strategists, Ella Baker). It was they who had been plowing the ground of political and social change even before the heightened activism of the 1960s, and it was they who were often killed — or destroyed in other ways — before they could even see the fruits of the seeds they’d sown.

By focusing only on a few “special” people like Dr. King and Rosa Parks — rather than highlighting, as Howard Zinn did, the stories of “ordinary” heroines and heroes — we fail to understand that most activists in the movement didn’t consider themselves “special” at all. They were simply people who chose to change things — chose to risk their lives, their livelihoods and possibly their personal dreams for the future to right the wrongs they could no longer ignore. Also important to students: many of those who were at the cutting edge of this change were young people. It is through the vanguard of the young activists of the 1960s that students will, hopefully, see themselves as the activists of today.

If we don’t learn that it was people just like us — our mothers, our uncles, our classmates, our clergy — who made and sustained the modern Civil Rights Movement, then we won’t know we can do it again. And then the other side wins — even before we ever begin the fight.

Video at the top of the page is from “Uprisings: Stories of the work of civil rights,” USA Today Storytellers Live Project, Sept. 24, 2020.

Background

From History Makers.

Film producer and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) activist Judy Richardson was born to autoworker William King Richardson and state office worker Mae Louise Tucker Richardson in Tarrytown, New York. Richardson grew up in the “under the hill” section of Tarrytown. Richardson’s father helped organize the United Auto Workers (UAW) local at the Chevrolet plant in Tarrytown and died “on the line” when she was seven years old. Richardson graduated from Sleepy Hollow High School in 1962 and was accepted to Swarthmore College on a full, four-year scholarship. Later, Richardson would also attend Columbia University, Howard University, and Antioch College.

Film producer and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) activist Judy Richardson was born to autoworker William King Richardson and state office worker Mae Louise Tucker Richardson in Tarrytown, New York. Richardson grew up in the “under the hill” section of Tarrytown. Richardson’s father helped organize the United Auto Workers (UAW) local at the Chevrolet plant in Tarrytown and died “on the line” when she was seven years old. Richardson graduated from Sleepy Hollow High School in 1962 and was accepted to Swarthmore College on a full, four-year scholarship. Later, Richardson would also attend Columbia University, Howard University, and Antioch College.

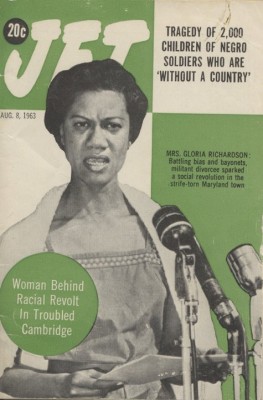

Gloria Richardson. Click on image to learn more about the Cambridge Movement. (No relation to Judy Richardson.)

During her freshman year at Swarthmore, Richardson joined the Swarthmore Political Action Committee (SPAC), a Students for a Democratic Society affiliate. In 1963, Richardson traveled by bus on weekends, with other SPAC volunteers, to assist the Cambridge, Maryland, community in desegregating public accommodations. The Cambridge Movement was led by civil rights activist Gloria Richardson, with assistance from SNCC field secretaries such as Baltimore native Reggie Robinson. Richardson eventually joined the SNCC staff at the national office in Atlanta, where she worked closely with, among others, James Forman, Ruby Doris Smith-Robinson, and Julian Bond.

When the national office moved to Mississippi, during 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer, Richardson relocated as well. Richardson also worked in SNCC’s projects in Lowndes County, Alabama (with Stokely Carmichael/Kwame Ture and others) and in Southwest Georgia. In 1965, Richardson became office manager for Julian Bond’s successful first campaign for the Georgia House of Representatives; she also organized a northern Freedom School to bring together young activists from SNCC’s Southern projects and Northern support offices.

Read more about Judy Richardson at SNCC Digital Gateway.

Publications and Films

In 1968, Richardson and other former SNCC staffers founded Drum and Spear Bookstore in Washington, D.C., which became the largest black bookstore in the country. Richardson was also the children’s editor of Drum and Spear Press. In 1970, Richardson wrote an essay on racism in black children’s books, published by Howard University’s Journal of Negro Education.

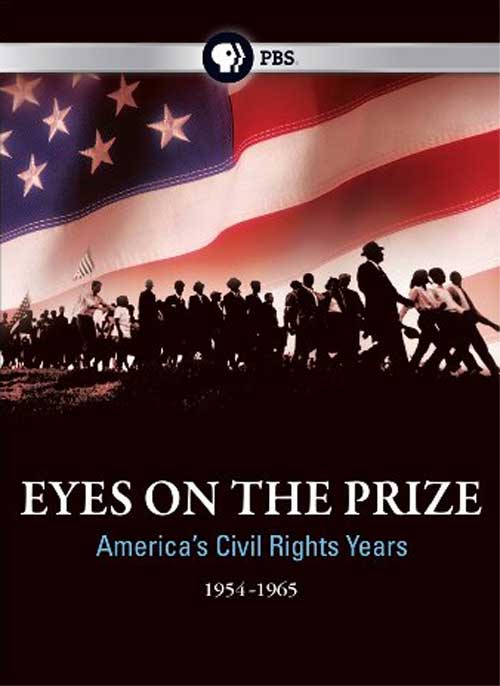

In 1978, Richardson began working with Henry Hampton and Blackside Productions on an early version of what would become the Eyes On The Prize series; major production for this Academy Award-nominated, six-hour PBS series began in 1986, during which time she acted as researcher and content adviser. For Eyes On The Prize II, the subsequent eight-hour series, Richardson was the series associate producer and then became education director for the full 14-hour series. Beginning in 1982, Richardson was director of information for the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice, participating in its protests against police brutality in New York City, and its bus caravans to the Alabama Black Belt to counter the Reagan Administration’s intimidation of elderly African American voters. Richardson later co-produced Blackside’s 1994 Emmy and Peabody Award-winning documentary, Malcolm X: Make It Plain (for PBS’s The American Experience).

In 1978, Richardson began working with Henry Hampton and Blackside Productions on an early version of what would become the Eyes On The Prize series; major production for this Academy Award-nominated, six-hour PBS series began in 1986, during which time she acted as researcher and content adviser. For Eyes On The Prize II, the subsequent eight-hour series, Richardson was the series associate producer and then became education director for the full 14-hour series. Beginning in 1982, Richardson was director of information for the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice, participating in its protests against police brutality in New York City, and its bus caravans to the Alabama Black Belt to counter the Reagan Administration’s intimidation of elderly African American voters. Richardson later co-produced Blackside’s 1994 Emmy and Peabody Award-winning documentary, Malcolm X: Make It Plain (for PBS’s The American Experience).

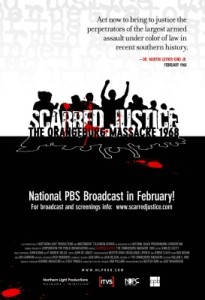

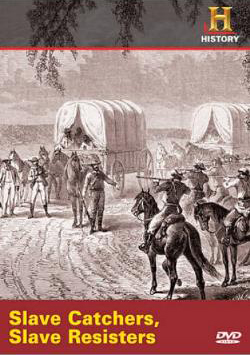

Serving as a senior producer for Northern Light Productions in Boston, Richardson produced historical documentaries for broadcast and museums, with a focus on African American historical events, including: a one-hour documentary called Scarred Justice: Orangeburg Massacre 1968 (South Carolina) for PBS; two History Channel documentaries on slavery and slave resistance; and installations for, among others, the National Park Service’s Little Rock Nine Visitor’s Center, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center (Cincinnati), the New York State Historical Society’s “Slavery in New York” exhibit, and the Paul Laurence Dunbar House (Dayton).

Serving as a senior producer for Northern Light Productions in Boston, Richardson produced historical documentaries for broadcast and museums, with a focus on African American historical events, including: a one-hour documentary called Scarred Justice: Orangeburg Massacre 1968 (South Carolina) for PBS; two History Channel documentaries on slavery and slave resistance; and installations for, among others, the National Park Service’s Little Rock Nine Visitor’s Center, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center (Cincinnati), the New York State Historical Society’s “Slavery in New York” exhibit, and the Paul Laurence Dunbar House (Dayton).

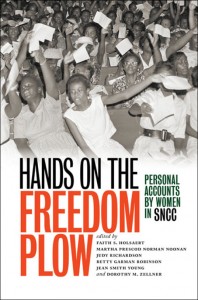

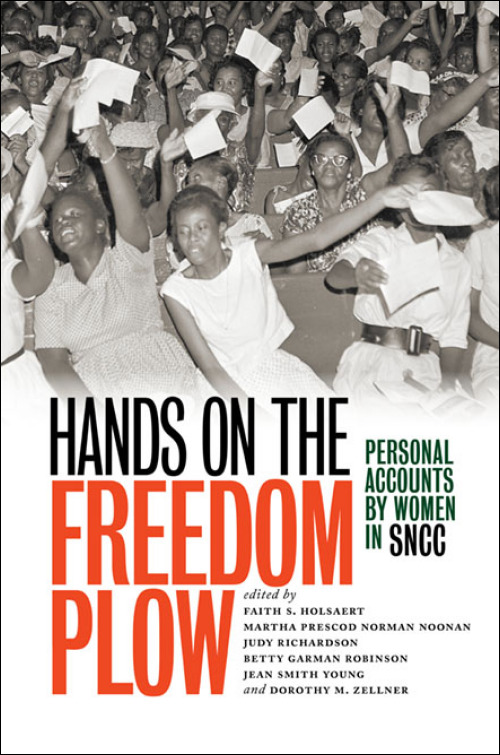

Richardson and five other SNCC women, edited Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts By Women in SNCC. The anthology, published by University of Illinois Press, includes the courageous stories of over fifty SNCC women.

Richardson and five other SNCC women, edited Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts By Women in SNCC. The anthology, published by University of Illinois Press, includes the courageous stories of over fifty SNCC women.

Richardson received an Image Award for Vision and Excellence from Women in Film and Video. She lectures, writes, and conducts professional development workshops for teachers about the history and values of the Civil Rights Movement and their relevance to current issues.

Richardson was awarded an honorary doctorate by Swarthmore College where she gave the commencement speech and became a visiting professor at Brown University in the fall of 2012.

—Biography from History Makers.

Talks, Interviews, and Primary Documents

|

“The Dream Marches On” by Ayah Awadallah, Howl Magazine (April 30, 2015)Helping UMass Lowell commemorate the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Judy Richardson, along with journalist, author and professor Charles Cobb, shared firsthand accounts with students and the public in April of 2015. In conjunction with the public programs, HOWL conducted an interview with Richardson about life on the front lines of a racial divide, and her thoughts on race today. (Currently unavailable online.) |

|

The Way We Were: The SNCC Teenagers Who Changed America by Judy Richardson in Women’s Voices for Change (February 26, 2015)Richardson shares the lessons she learned from her work in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Read at Women’s Voices for Change website. |

|

Judy Richardson on the Local Organizing that Produced the Civil Rights MovementPresentation by Judy Richardson for the MIT Center for Civic Media on the local organizing the produced the Civil Rights Movement, March 2012. Read the presentation recap at MIT Center for Civic Media. |

|

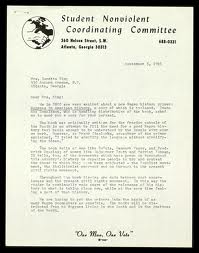

SNCC Letter to Coretta Scott KingLetter Judy Richardson wrote on the behalf to SNCC to Coretta Scott King on Sept. 5, 1965, to give her a copy of the new book Negroes in American History. The book serves as a method of teaching children about African American history while tying in elements of the Civil Rights Movement. Read response from Mrs. King. |

|

Hands on the Freedom Plow Panel with the Women of SNCC (Video)

|

|

History Makers interview with Judy Richardson on April 9, 2007“Film producer and former Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) activist Judy Richardson was born to autoworker William King Richardson and state office worker Mae Louise Tucker Richardson in Tarrytown, New York. Richardson grew up in the “under the hill” section of Tarrytown.” Continue reading. |

Awesome! And so needed in this vale-of-tears world. It gives one HOPE!