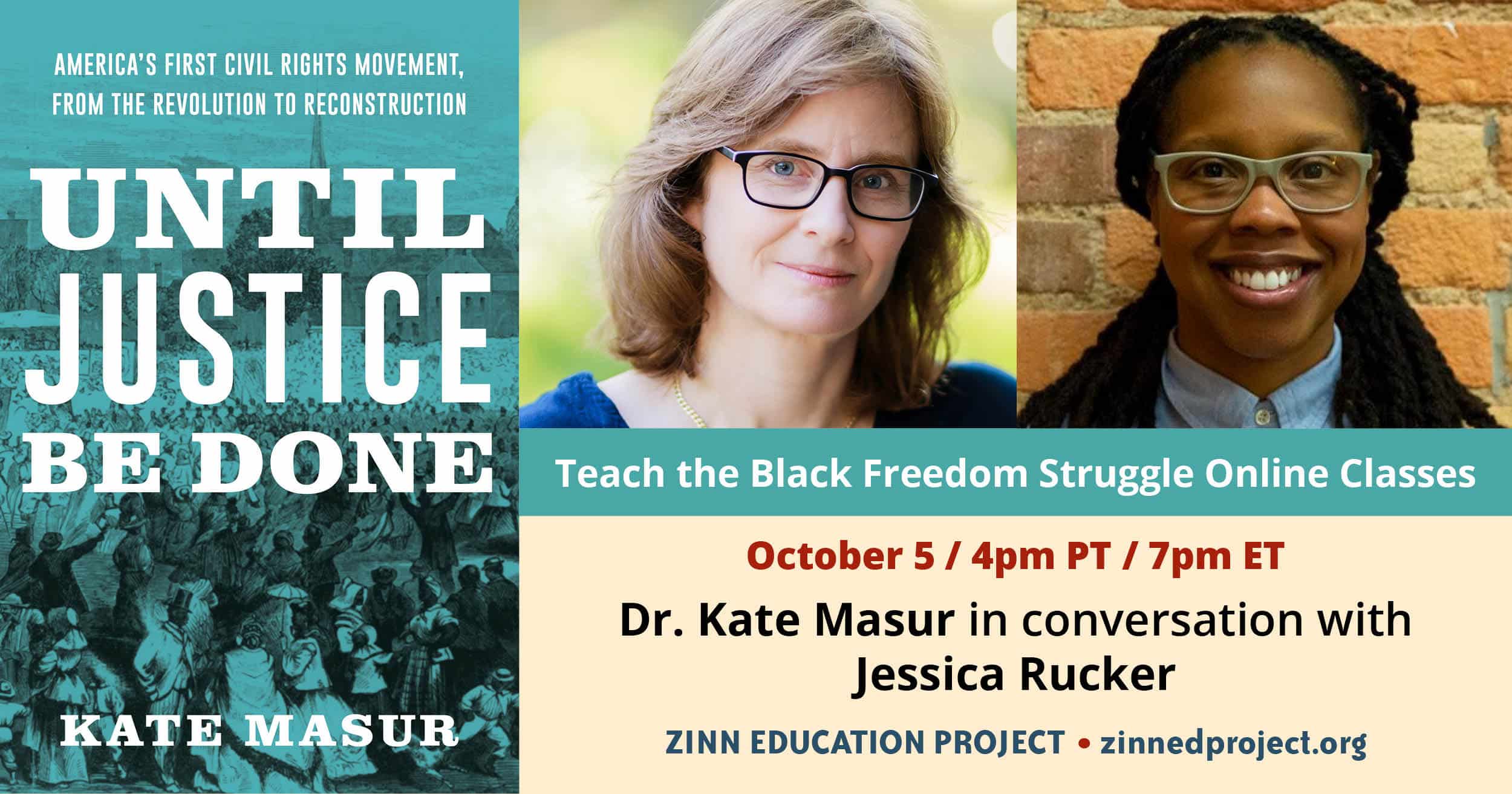

Teach Reconstruction campaign adviser and Northwestern University history professor Kate Masur joined high school teacher Jessica Rucker on Tuesday, Oct. 5, to speak about the people who courageously battled racist laws and institutions, North and South, in the decades before the Civil War. Masur’s book, Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, From the Revolution to Reconstruction, tells this story.

Here are a few reactions from the participants:

The entire talk was fascinating to me. I teach this history but not as part of the continuing civil rights movement.

I liked the focus on stories to teach history. Just first person, primary document stories. I think the kids would like and connect with them to learn.

The most important thing that I learned today was the Black resistance against laws and treatment in the Northern states of the U.S. The white backlash and charges against Blacks echo today in the white supremacy and proposed laws to limit voting and elections.

Just even learning the concept of a civil rights movement that took place pre-Civil War is enough. Again, another piece of hidden history.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion. Jessica Rucker: Hi, I’m Jessica Rucker and I’d like to welcome everybody to our class with Dr. Kate Masur. Some of you are joining us for the first time, over 50% of you, and some of us have participated in our spring series. It’s been really a gift to share this time together and I want to thank you again for being in virtual community with us. Alright, I think we’re ready, I think it’s that time. So, we’re going to start our conversation, and after about 25 minutes we’re going to pause so that you can meet each other and talk in small groups, and share your thoughts with one another. I feel so excited and so lucky to be joined this evening by Dr. Kate Masur. Kate Masur is a professor of history at Northwestern University. In addition to this awesome book, Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, From the Revolution to Reconstruction, she’s also an author of An Example for All the Land: Emancipation in the Struggle Over Equality in Washington, D.C. Great, great books. Kate Masur is also an adviser to the Zinn Education Project’s Teach Reconstruction Campaign, which will be releasing a national report on the teaching of Reconstruction this fall. So, speaking of Reconstruction, I encourage everyone to visit the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s new special exhibit on Reconstruction. If you’re in D.C., do check that out. All right, Kate, can I call you Kate tonight? Kate Masur: Absolutely. Jessica Rucker: Alright, awesome. I am so excited to get into our conversation tonight. I’m learning so much. Let’s start actually with the title; I feel that the title was very compelling. So, tell us a little bit about how or why you chose to title the book Until Justice be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, From the Revolution to Reconstruction? Kate Masur: Well, first, thank you. I just want to thank everyone at the Zinn Education Project for making this event happen. As you mentioned, I’ve been an advisor on the Reconstruction project and it’s such an honor, really, to be part of this wonderful series and to be here with so many educators of different kinds. So thank you for having me. And Jessica, in particular, thanks so much for taking the time and engaging with this book. So the title, it was interesting to just think back on that. First of all, the first part of the title — Until Justice be Done — I was interested in finding a small and telling quote from the book to use in the title, and this title is a phrase from a source that I cite in the book. It comes at the end, the phrase, Until Justice be Done, actually comes at the end of a petition created by Black residents of Ohio to petition the state legislature for repeal of what we call the Black laws. I’m sure we’ll get into what those laws were and stuff like that, but by 1837, a group of Black Ohioans was trying to organize across the state to petition the legislature to repeal these terrible racist laws. I found their petition published in an anti-slavery newspaper published by white anti-slavery activists out of Cincinnati, and in that October 17, 1837 issue was the petition in which this group of people call for repeal of these racist laws of the state of Ohio, which particularly deprive them of the right to testify in court. They say that race-based laws are unjust on their face, and they defend themselves as taxpayers from the state of Ohio. They conclude their petition by saying, “and from the exercise of this inalienable right of freely expressing our opinions, they can never cease until justice be done.” So, in that quote, they’re talking about, they will keep on this work until justice be done, until we see this change that we want. I really liked that it was sending a message that what this book is about is about a long struggle for justice, one that started way back in the period I’m talking about — I mean, certainly, in many ways started before, and in many ways continues to this day. I’ll just say one quick thing about the second part of the title, America’s First Civil Rights Movement, From the Revolution to Reconstruction, I was struggling with what should come after the colon and the title of my book, and I can’t take full credit for this one. My editor and I were going back and forth about what words should be in that part of a title and what kind of message do you want to send. When we arrived at America’s First Civil Rights Movement, it was kind of an aha moment because, first of all, it’s obviously a title that will hopefully cause people to connect this story to what they know to be the Civil Rights Movement, which we usually associate with the 1950s and 60s. It kind of immediately tells you something about what you’re probably going to read about in this book. But the other thing that I liked about it, when we finally came up with this was this is really a book about people struggling for racial equality in civil rights, as people in the 19th century understood civil rights. So there’s a fair amount in the book about how people defined what civil rights were, and then calling for racial equality in those rights, and part of what I write about in the book is how people actually distinguished, at the time, between what they considered civil rights and what they considered political rights. That’s maybe something we can also talk about. But when we finally came up with that title, I was like, “Oh, that really is helpful in a way to remind, to telegraph, right away that this is about a struggle for racial equality and civil rights that people probably mostly don’t already know about. But they can help think about it by putting it in the context of things that are more familiar from the 20th century.” Jessica Rucker: It’s amazing because I tell you this title alone was enough for me to say, “Oh, wow, I owe some students some apologies,” because I taught in 2018–2019 an introduction to the Civil Rights Movement class, and one of the first questions I asked students was to identify some historical figures from the Civil Rights Movement. Students would say stuff like Martin Luther King, Frederick Douglass, and I used to giggle under my breath. Frederick Douglass? But now it turns out this is the Civil Rights Movement before the Civil War. So now I can go back to those students and say, “Actually, you are also right, because our history has history.” So thank you for that compelling title that just invited me right in. Let’s swing into the book a little bit. From what I’ve read so far — and it is just juicy, I got my little tabs for things I want to come back to — your book focuses largely on the antebellum period and addresses what we’re going to call right now the Civil Rights Movement before the Civil War. I’m kind of a visual, theatrical kind of person, so if the antebellum period was a stage in U.S. history, break this down like a story. So, what will be the plot? What’s the setting? Who are the characters? Describe the conflict for us and then say a little bit more, because you were leading into this, how the antebellum period connects to today. Kate Masur: Okay, big question. I think I’ll just start by giving some of the touchstones of this period, as it’s conventionally thought of. I mean, the antebellum period is usually considered like the 1830s until the Civil War starts, so it’s the decades that immediately come before the Civil War. There are many ways that we can talk about this period. Generally speaking, a lot of times the way that it’s talked about is we’re going to spend some time in this period talking about why the Civil War happened. So the Civil War continues to be a major turning point in American history. One of the questions that’s defined the study of the antebellum period is accounting for this sectional conflict. So you have in this period the Mexican-American War, you have in this period the Compromise of 1850, you have the Dred Scott decision, you have this kind of march — in a way it’s sometimes taught as a march toward war. It’s also a period that starts before the 1830s, but of the expansion of the right to vote for white men. We know this history of the gradual dropping of qualifications like taxpayer or property owner for white men to be able to vote, even as in many northern states and some southern states African American men were disenfranchised. This is a period when in most places it’s only white men who are allowed to have the right to vote. The Seneca Falls convention is another touchstone in this period, the growing movement for rights for women, including women’s right to vote. I would just say within my book and the stories that I’m interested in telling here, I focus on the northern states primarily and one of the key things that helped me think about what I was doing here was thinking about those northern states as post-slavery societies. So, one of the things we have to keep in mind is that slavery, the institution of slavery, was legal throughout the British colonies of North America at the time of the American Revolution. Then what happens is the northern tier of states goes on to abolish slavery in a variety of different ways, mostly gradual, sometimes not. The states of the Midwest, which I spend a fair amount of time talking about, came in when slavery already existed in what was known as the Northwest Territory — they came in with a bar on slavery and a tendency to end slavery there. But at the same time, as I write about in the book, most of those states — especially the ones like Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana, bordering on the Ohio River — passed laws that explicitly discriminated against free African Americans. One of the key starting points of my book is that there was actually a very large, complicated, intensely fought debate about racial equality and the rights of free African Americans in the free states that covered just about all the same issues that you would expect to see in Reconstruction. In that post-slavery moment where slavery is destroyed throughout the United States we see all of those same issues debated and hashed out in the antebellum north. So that’s one of the key ways that I want us to think about these debates and these conversations is this: beginning with the abolition of slavery, racial slavery anywhere raises questions about what is the future of communities? What is the future of a nation when you have lived with the institutionalization of race-based slavery, and in the case of the United States, settler colonialism to regimes of racial inequality? How do you then come to grips with it? So the discussion in my book is a lot about various debates ranging from the white Americans who believe there actually could never be a place for free Black people in this country and advocated for what was called colonization, or the idea that free African Americans should leave the country because there never would be a space. You either could be a free person, in which case you were a white person, or an enslaved person of African descent, and they had no room in their imagination for a multiracial nation. So, all the way from those folks on the one hand, to the people I tend to focus on in the book — who are the people who envisioned something quite different, who envisioned multiracial society, envisioned some forms of racial equality and envisioned some forms of racial justice. This is the kind of cauldron of issues that I’m writing about in this book. Jessica Rucker: First of all, there’s so much to be quoted and tweeted here, but this notion of the racial imagination, and this is what was coming up for me as I’m reading your book. First I’m like, “Oh, it was this many free Black people petitioning, using the courts, using the press to expand their freedom.” That was the first aha moment. I’m saying this as a teacher of U.S. history, I was like, “Oh, for real?” But what you were just talking about, the racial imagination. I am my ancestors’ wildest dreams. It’s just so uncanny that some of the tactics that you talk about in terms of the future of African American communities, the level of vision that Black folks had is so similar to conversations that we’re having now. But I’m going to stick with the antebellum period. Let’s keep unpacking this. You’re talking about resistance to oppression, quite a bit of very intentional, racialized oppression. I forget what Clint Smith calls it, it’s not the dehumanization, but this attempt to dehumanize humans who are Black people, right? So, what did resistance look like during that era? Then, how is it different or similar to what we know now as the Civil Rights Movement of the 50s and 60s, or even to today? I mean, you tell some great stories from that era, specifically of African American people. Kate Masur: There were a lot of ways that people mobilized to resist the racist public policies that they confronted. One of the things that I want to get around to talking about is direct action. So, people were very savvy in their political organizing and they would identify what is the best venue to make the kinds of changes that I want to make. They were not going all Helter Skelter, like, I’m not sure where I want to direct my protest. But, like I said in the example of the petition from 1837 that I mentioned, these were Black Ohioans who first met in Cleveland to develop this kind of organization and then sent somebody named Molliston Madison Clark throughout the state talking to people about the conditions in which they lived or urging them to sign petitions to the state legislature. They knew that the state legislature was responsible for the laws that oppressed them and so their attention was being directed at the legislature, and they were going to petition. Now one of the things that’s really interesting to think about is African Americans, for most of the time that I’m writing about, were only about one percent of the population of the state of Ohio, and African American men were prohibited from voting. The state constitution said white men only are allowed to vote. So if you want the laws to change in your state, how actually do you make change when the people who care most about the issue are a very small minority of the population and also can’t vote? This is where petitioning comes in. Petitioning was supposed to be available to anyone, you did not have to be a voter to petition, you did not have to be a man, you did not have to even be an adult, you didn’t have to be a citizen. By tradition, going way back in time, anyone can petition the government and anyone is entitled to a response. So what would happen when these folks petition? Let me just sidebar for a second to give a better sense of what they did. So petitioning involved, as I mentioned, with Molliston Madison Clark, he went throughout the state talking to people on a very local level, petitioning, you would go door to door and ask people to sign this petition and in the course of doing that you would be explaining, here’s the issue, here’s why we should care about it, here’s why you should sign the petition. People could also develop petitions in churches, right? You could be at church on Sunday, and afterwards people could be walking around talking about the issue and distributing the petition. The act of gathering signatures on a petition itself, as I think we can imagine from the present day, is an act of organizing. It is an act of helping people develop a consciousness about an issue that this movement cares about. But then you might say, “Well, why would they have any hope of even doing this?” I mean, they’re just this small minority of people who probably the racist government of the state doesn’t really want to do anything that they want them to do. That wasn’t quite the case, and it partly has to do with the fact that there was a tradition that when people petitioned, the government was obligated to take their petition under consideration. So, what would happen in the Ohio legislature, for example, is the petition sent in by African Americans, plus the petitions that were sent in for repeal of the Black laws by white people, would be grouped together and sent to a subcommittee and the subcommittee’s charge would be to report back on do you think that these petitioners wishes should be granted, that they want to repeal these racist laws of the state? And usually what would happen, until 1849, was this subcommittee would come back and say the answer is, “No, we do not think that we should repeal the laws,” and they would say all kinds of crappy things about why they believe that they needed these laws that were designed to oppress and marginalize African Americans in the state, and to discourage migration of Black people into the state. But, here’s why it still mattered, even if they didn’t win the issue then: Number one, these activists would then publish in newspapers the really racist reports from the state committee and critique them. They would put them on display and say, “Look what the Ohio legislature is doing now. Look how horrible, look how unjust, this is.” And the other thing that could happen is sometimes the committees were divided. You might have a three person committee from the legislature where two people say “We’re keeping these laws,” and one person says, “I think we should repeal that.” That itself is going to be a win, right? Then the activists are going to publicize that minority opinion and say, “Look, we’ve got this guy saying all the right things about our issue. Now we just need to get more people on board.” So, they’re using organizing, petitioning, and the media that they have at their disposal to get the word out. And these are just some examples of how, even though they were in a position of not a lot of strength for a lot of this period, they’re making the most of what they’re doing. And they actually are successful in gaining support for the issue. Jessica Rucker: I’m getting so fired up here because I remember reading in the book how you describe petitions published in the paper. So I would get my paper and I could cut it out, unlike that, that is at some street level gorilla, I’m going hard by any and every means necessary [kind of thing]. I just felt so inspired. They reminded me of my days as an organizer, door knocking and petitioning — that that is not like work. I’m thinking to myself, again, this is America’s first Civil Rights Movement before the Civil War, when the country is still at odds with itself around whether or not this peculiar institution, so to speak, should still exist. My folks are putting the petitions in the newspaper, like “Yo, cut this out. You go talk to those folks. We’re going to talk to our folks,” and it just was super inspiring. We’re going to go off script a little bit. Let’s talk about D.C. I was both excited yet frustrated about the story of Gilbert Horton and my home city of Washington, D,C. So, unpack him and his situation a little bit for us. I think this is where we get to the National Intelligencer. I’ll let you do your thing, but tell us a little bit about what happened there. Kate Masur: Sure. Let me say, some parts of the book are about the stuff we’ve been talking about now, where it’s state level activism, trying to repeal racist laws at the state level. These laws were, different states had different types of laws with respect to race and racial discrimination and the worst perpetrators in terms of having just a whole range of these types of racially restrictive, racially discriminatory laws, the worst perpetrators outside the slave states were Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. So, I spend a certain amount of time on those states. But then the other thing I look at is the problem or the challenge of African Americans in interstate travel and interstate migration. This is an issue where the question of racial equality and civil rights comes to the federal level sometimes. To give one example, and it is a D.C. example, [that is] just super interesting because of how it all played out. There was an African American man named Gilbert Horton, he was originally from New York, he was enslaved when he was born, and his father actually earned enough money to purchase Gilbert’s freedom. His father evidently was a free man already and purchased Gilbert’s freedom. They’re from rural Westchester County, it’s not so rural now, but they’re from a rural area. Gilbert Horton moves to the city of New York and he gets a job as a sailor on ships that go up and down the Atlantic coast of the United States. This was a pretty common job for free Black men who lived in places like New York and Massachusetts and Philadelphia, Atlantic port cities in the northern states, to get jobs on ships. These were decent jobs in a racially discriminatory job market. These were decent jobs for African Americans, they paid pretty well, there was a fair amount of independence in these jobs, and you got to travel. So Gilbert Horton is on a ship, he’s working, he’s a sailor, and then for some reason, we don’t know why, he gets off his ship when it’s in port in Norfolk, Virginia and he makes his way on his own to Washington D.C. Now, D.C. at that time, was a jurisdiction where slavery was legal. It was a complicated place. If you know about the history of D.C., you will know that the free Black population was pretty large and growing. So, by the time 1860 comes around, the vast majority of African Americans who live in the District of Columbia are free rather than enslaved, but it is still a slave holding jurisdiction under the thumb of slave owners and their interests. So, various attempts to abolish slavery in Washington or make the city more of a beacon of freedom have already failed and will continue to fail in the future. Among those laws and policies in D.C. were laws very characteristic of any slaveholding jurisdiction, which were any person of African descent who was out at large on the streets was considered, their assumption was, that they were an enslaved person, perhaps on the run, rather than the assumption that they’re a free person. So, sometimes that legal principle is called the prima facie principle. In other words, that they’re Black or dark brown skin is prima facie evidence that they are enslaved and the onus is on them to prove that they are free. This was the policy in D.C. and everywhere in the slave states, and this gives you a sense, and I think this is a really critical thing to think about, this very long history of people of African descent or people who don’t appear white, being subjected to special suspicion, being subjected to doubt or assumptions about criminality, that really does go all the way back. So Gilbert Horton comes into Georgetown, this happens on the wharf at Georgetown, which is part of the District of Columbia, some white man comes up to him and says, “Oh, I think you’re probably a fugitive from slavery and I am going to call the constable and we’re going to put you under arrest.” And he says, “No, I’m a free man from New York State.” And they say, “We don’t care. We’re going to put you in jail. Then, according to policy, we will advertise.” The idea here is they’re advertising for the person’s supposed “owner” to come show up and pick them up from jail. Typically, the rule was, if you could not prove your freedom and no one came to get you, you could be sold into slavery. So the stakes for people, Gilbert Horton and other people who got in this situation, even regardless of what their actual backstory was, were incredibly high because they could have actually ended up being sold into slavery. What happens, however, thanks in part to print culture and the circulation of newspapers, the Washington Intelligencer, which is one of the most prominent papers, publishes the ad that’s been placed for Gilbert Horton. The paper makes its way to New York State, where people who know Horton see it, and they say, “Wait, wait, wait, this is Gilbert Horton. We know Gilbert Horton.” As I mentioned, his father was a free man, they lived in Westchester County, they knew a white man named William Jay, who is the son of John Jay, one of the founding fathers. William Jay had a problem, had an issue, with this. Generally, William Jay was anti-slavery, he was a very interesting constitutional thinker. So, people in Gilbert Horton’s community, Black and white people, mobilized to provide the evidence that Horton would need to prove that he was a free man. They send that evidence to D.C., they get the governor of the state of New York involved, DeWitt Clinton, they get the President of the United States involved. And Horton, after spending about 30 days in prison and in jail in Washington, is ultimately released. Gilbert Horton stays in Washington for a while — it’s kind of interesting and hard to know why he decided to stay there — but he is eventually able to prove his freedom and be released. But, obviously, this was an incredibly close call. If nobody had seen that ad who knew him, or if he hadn’t had papers that could be sent to Washington, or if he were just a guy who wanted to be free in Washington D.C., none of this would have turned out the way that it did. Among the many reasons why I think this is a really interesting story is people in the north who disagree, who’ve had a problem with the arbitrary arrest of free Black northerners, made this into a kind of cause célèbre. Newspapers all over the north published updates about Gilbert Horton, and people generated a lot of outrage. Gilbert Horton’s congressman, a man named Aaron Ward, who represented that district in New York, brought it up on the House floor, and may and kind of argued that there needed to be an investigation into the laws of the District of Columbia. They argued that Gilbert Horton was a citizen of the state of New York, and as a citizen, he could not be treated this way, even when he was traveling in a slaveholding jurisdiction. This case of Gilbert Horton also brings to light both the dangers that free Black people faced when they were traveling in places where they weren’t known, where they were new in town, particularly in slaveholding jurisdictions but not only, and also some of the movement, this first Civil Rights Movement that gets galvanized around cases like this, to argue that the United States needs to do better, that we need something better than just allowing this kind of thing to continue. Jessica Rucker: Thank you for sharing that story, because as I was reading about Horton, I was absolutely terrified. Like literally, legitimately like looking over my shoulder like this is terrifying. I liken it to conversations that we have today with students, you know, “just pull up your pants, just work hard and go to college.” I live in the middle of D.C., in Columbia Heights. My brother’s probably, I don’t know, 5’ 10”, 5’ 11”, a few 100 pounds, he’s a generous size too, and he was coming to visit me and the cops jumped out, like, “You fit the description.” So I’m thinking of Gilbert Horton, without our proximity to whiteness, our Blackness is not safe if white people don’t feel safe, right? If he didn’t have his freedom papers, though. I’m college educated, I work for such and such, no, I’m coming to see my sister. No, here’s her address. We have to have all these things just to prove that we have the human right, the inalienable human right to exist in public space. Then, this is on top of people who describe Black people as vagrants, as lazy, as they had worked and actually purchased this freedom, right? It’s just like no matter what we do it’s not enough. The last thing that really resonates with me about the story is what you said, the mass mobilization, the amount of base building and community-based use of media of the day, the role of relationships, all the different people who convene to say, “Hey, no, that’s Horton.” It was absolutely terrifying, though, absolutely terrifying, because I’m like, “Where was he in D.C., when he got snatched?” Do I visit that place? But anyways, I can go on and on. At this time, we are going to head into breakout rooms, but when we come back, we’re going to continue this conversation. So, please don’t drop off because again, we’re talking about America’s first Civil Rights Movement before the Civil War. Kate, were you about to say one thing before we went into the breakout rooms? Kate Masur: No, we can go into the breakout rooms. Maybe we can talk later about teaching this great pamphlet by James Fortin. He writes it in I believe 1813, where he’s writing about if the state of Pennsylvania were to pass laws like Ohio already had, how it would cause anyone who’s coming to visit him to be suspect, how it would empower racist constables. I mean, all of it is there, and I think it’s just such a remarkable source. So I feel like making those connections, that’s one of the places we could go and we can provide that source too, it’s available. Jessica Rucker: Right? Yes. Welcome back, please light up the chat. I’m curious, I want to see some highlights from your breakout groups. In the meantime, I want to ask Kate just a couple more questions and then we’re going to open it up to the virtual space. So Kate, I would love to fast forward to chapter seven, where you introduced me to John Jones and Mary Richardson. I’ve got to really emphasize this date, we’re talking 1841, so we’re still before the Civil War. They live in Alton, Illinois. Can you tell us what Jones’s life and activism teach us about what you describe as the northern debate about the right to free African Americans? How does his story fit into this broader story of America’s first Civil Rights Movement? Feel free to also share with us some additional ways or expand on the ways you’ve already described that African Americans were being described in public discourse by white people, particularly lawmakers, and then law enforcers, or vigilante law enforcers. How did that mischaracterization inspire this activism and organizing that we see during the period? I notice that’s loaded, that’s a lot, it’s like fifteen questions in one, but . . . Kate Masur: I’ll just dig in, and then if I miss anything you can remind me to come back to it. So, I’ll start a little bit, because we’ve been talking about these racist laws in the free state, let me just say a little bit more about that, especially for those of us who live in or have connections to places like Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana. Illinois, where I am now, and this is where I’m from. Actually, many people aren’t really aware of this part of the story, but these states border the Ohio River. If you think about American geography — and I spent a lot of time thinking about the Ohio River as an internal border within the United States when I was working on this book — these are free states that are on the north side of the Ohio River, right adjacent to slave states. A lot of white legislators in these states had a fear that African Americans were going to migrate into the states, coming across the river from slave states, in particular, whether they were people who had become free and still lived in the slave states — and there were thousands and thousands of free African Americans who lived in the slaveholding states, which we often kind of forget or don’t necessarily notice. So, whether they had already become free or they were escaping from slavery and seeking freedom, many of these white legislators and white residents were really worried about the idea of a growing Black population in their states. This goes back to what I was describing before about how there were these white colonizers who thought that there was really no place in the United States for free Black people. They simply couldn’t imagine a multiracial democracy. They weren’t necessarily all colonizers, but they advocated these laws that, for example, require free African Americans to register when they come into a county with local county officials; they have to pay a registration fee; they have to get people to put up bonds that are sort of promises that people will not get arrested or not become a public charge. They’re not entitled to testify in court cases involving whites. When public school systems are established in these states, African American children are excluded from them. One kind of rhetoric, and often people find this to be very resonant with present day issues, is the rhetoric that many of these white people use is to say, “I’m not racist but . . .” or some of them will say, “Alright, I actually am very racist. And this is why . . .” But some will say, “I just think that people coming from slavery, they’ll be dependent. They’re poor. Poverty is a problem. They don’t know how to work because they’ve spent their lives enslaved. I mean, yes, they worked, but they were coerced to work in slavery. So now they’re going to come into our states and become dependent on public charge, or on public resources, and that’s going to be expensive for us.” So, they make all of these justifications in the name of the public good, what’s good for our community. They would say this is just not good for our community, these are not a desirable group of people in our community. So, really one of the things that interested me a lot about that facet of this is the conflation of language of class with race, and these notions of poverty that are racialized already — all the way back then. The ways that people talked about Black migrants, the ways that people talked about Black poverty. In fact, there’s a great rejoinder from a guy named David Blackmore, who identifies as Black in his writing. He’s writing in a white Quaker newspaper, as early as 1817, and he responds to that argument, he said, “We might be poor, but if we are, it’s because our ancestors were brought here in chains and never paid for any of the work that they did. And not only that, these laws are counterproductive, they’re ineffectual, [and] we’re migrating into Ohio anyway.” He says things like that. This is the kind of stuff that people are up against, the acceptance of these arguments, the acceptance of these ideas. So to get back to John Jones, John Jones was originally born in North Carolina. He was born free it appears, but his mother was an African American woman [and] his father apparently was a German immigrant. He was free and his mother sent him to Memphis as an apprentice. So he was free but he wasn’t really free because he was apprenticed out, so once he was an apprentice he didn’t have a choice about whether to really be there in that line of work. But the good thing about being an apprentice is he learned a trade, so he became a tailor and that served him very well going forward to have a skilled trade. He ends up ending his apprenticeship in Memphis. While he was there he met Mary Richardson, and she was from what seems to be a very interesting free Black family as well. I’ve been doing a little bit more research on them as part of a project that’s associated with the Colored Conventions Project. We’re doing this web exhibit on the history of African Americans in Illinois in the 1840s and 50s, and through that I’ve learned some more about Mary Richardson’s family. Her family, they pass through Memphis and eventually they land in Alton, Illinois. When John Jones completes his apprenticeship, he goes up to Alton to be with Mary. They got married in Alton, and then they moved to Chicago in 1845. Chicago at this point is a very growing city. Chicago only really grew up as a big city starting in the 1840s. African American migration into Illinois had actually been mostly in the southern and western parts of the state that bordered on Missouri and Kentucky. So, Chicago was only becoming what it would later become as a hub of commerce and a hub of Black life, just in the 1840s. Mary Richardson and John Jones were part of creating a really amazing, and I think underappreciated, activist Black community in Chicago in this period. Around that same time, they found the first AME Church in Chicago, it’s called Quinn Chapel. The first Black Baptist Church is also founded in Chicago in the 1840s. So they’re building institutions. Jones begins writing extensively about what is wrong with Illinois Black laws, and he is writing in the Chicago Tribune. When it’s first published, they published a series of articles by him about not only how Illinois should repeal its racist laws that exist — I mean, that’s the civil rights laws — but Black men should also have the right to vote. He’s just out there saying, “We want full citizenship. We want every single right that white people already enjoy.” Jones is one of the best known of these Black activists in Chicago — I should say they’re very closely associated with what we know as the Underground Railroad also. So in other words, in addition to petitioning and trying to get the Illinois laws repealed, they’re all constantly helping people who are escaping from slavery get to freedom, and Chicago is a really, really important point on that route. Because if people, especially from Missouri and Kentucky, can make their way across the state of Illinois, get to Chicago where there’s a relatively extensive network of Black and white people who are willing to participate in this, they can take either a train or a boat across Lake Michigan, over through the Great Lakes either to end up in Detroit and crossing over from there into Canada, or other points east and into Canada. So their networks also become really important for subverting slavery in that respect. So, Ohio is the place where this Civil Rights Movement is most effective in getting laws repealed, and they do manage to get most of the Ohio Black laws repealed in 1849. Illinois is a much tougher nut to crack because it is dominated by the Democrats who were the most conservative, more racist, of the two political parties. But Jones and his coalition of people based largely in Chicago keep at it. I mean, he just keeps working at it. They formed a statewide organization in the 1850s, and they continue to press for repeal. And finally, it’s not until 1865, right before the first federal civil rights laws passed, they succeed in getting the Illinois legislature to repeal those laws that they’ve been fighting against for so long. So, their story is really remarkable, and I’m looking forward to talking more about them, particularly in the context where I live, here in the Chicago area. Jessica Rucker: Amazing, Black love and Black movements. This just made me think about Charlene Carruthers’s BYP100 and the Chicago style of organizing. As I’m listening to you talk about Jones and Richardson, I’m like, wow, again and again, our movements have roots far past the 1900s into the 1800s. And this is just, my mind is blown. So, before we go on I just have to say, please y’all, check out this book. I don’t want anybody leaving this space today having your students think that Lincoln freed the slaves. We have overwhelming evidence that we freed ourselves. There’s no justice, there’s just us. I want to ask you many more questions, but just in the interest of time and practicing equity, I’m leaving space for other people to ask questions, let’s end this part together on this question right here, “Hi, how did America’s first Civil Rights Movement shape federal policy?” And then this is the real big one, “Spoiler alert if you haven’t got to the end of the book yet, what did it accomplish?” But still read it. Read it, y’all, it’s different when you read it. But I want to hear it from Kate. Kate Masur: I think that when we ask questions about social movements — like did they succeed, or did they fail, how do we evaluate success — I think it’s complicated. Most movements for racial justice do not get all that they want, so we need to look and think about what constitutes success here. Like I said, I mean, there’s a very clear success in Ohio, where they do succeed in repealing the Black laws. But my argument in the book is that this movement was highly successful, and part of the reason that we don’t already know about this movement is because we take for granted the principles that it advocated, and so it became invisible. So, when you think about the reality that in the free states it was entirely possible, and in fact happened, that you could have these laws that literally said “free negros and mulattos,” this, that and the other thing, that explicitly discriminated based on race, and that was widely accepted, there was — and we haven’t really had a chance to talk about this — but there was not considered to be anything unconstitutional about those state laws, not to mention the laws of the South, which permitted and advanced human bondage. To get to a point where you have three constitutional amendments that not only abolish slavery but also declare the principle of equality before the law, and that every person is entitled to due process of law, and that every person born in the United States is a citizen, and then a 15th amendment that embodies the principle of no racial discrimination, we have to ask the question: How did we even get the principle of no racial discrimination into our federal policies? We cannot take for granted that it’s there. It wasn’t there from the founding, it only got there in the 1860s. So why is it there? Because of this movement, and because of the Civil War. I mean, it’s because of this movement, and also because there was a huge crisis in this country that made constitutional change and legislative change possible that never would have been possible before. So that’s a key part of it, too. It is partially about their creativity, their perseverance, their values, their ability to persuade people, and it’s also that they had the good fortune to live in this moment of crisis where all kinds of new things were possible. They stepped into that moment, prepared with a set of ideas that were antiracist ideas, and they were able to enact those at the federal level for the first time. And that takes the shape of the three constitutional amendments that we’re familiar with, as well as the nation’s first ever federal civil rights laws. The first one was the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Then there’s several more civil rights laws passed at the federal level in 1870 and 1871. Instead of assuming that this nation would ever get to that point, if we ask the question how did we get there, the answer has everything to do with this movement and the people like John Jones and Mary Richardson Jones, and the people who wrote those petitions and went door-to-door and put this issue on people’s agenda. That’s the point that I want to make in the book. And that is obviously not to say that we get all those federal policies during Reconstruction and we all live happily ever after. I mean, we all know that that is also not the case. But this country would not have gotten as far as it did during that remarkable period of Reconstruction if that movement hadn’t paved the way. Jessica Rucker: Thank you. I mean, y’all heard it first, right here from Kate herself, who did the research that African Americans, [and] our white allies of conscience, were fighting for America’s first civil rights. I think both Bill Cosby and Kanye West, I wish they could be here tonight. Long story short. So, now I am going to turn it to the chat. This is your opportunity, and thank you all for sharing what you learned and what you discussed in the breakout rooms. We have a little time, so if there are any questions we want to try to answer them, so just go ahead and throw them in the chat. Okay, Kate, while folks are thinking through their questions, let me ask you this one, “I’m a high school teacher, I’m going to be talking to my colleagues, actually, we have a grade level meeting tomorrow. If you were to give me a soundbite of why it’s important to teach America’s first Civil Rights Movement and why it’s important to situate it during the antebellum period, and not just the 20th century, what would you suggest that I tell my colleagues tomorrow?” Kate Masur: I think if part of the point is to highlight the Black Freedom Struggle and the continuity and long history of the struggle to make a more just, less racist country, then I think the key points to bring out are the people who were fighting this fight — even before slavery was abolished — particularly in the free states where Black people faced so many discriminatory policies, so much oppression, that people were raising their voices, people were talking about how to oppose these policies, what they could do, and we have the sources. So, if you want to bring this into the classroom, there are so many sources, and I would love to recommend some and work with you at the Zinn Education Project to highlight some of those. I guess one of the things I think about, and I don’t know how people are teaching in their classrooms, but the only story here is not the story about the debate over slavery and the coming of the Civil War right there, it’s also the only social movement story, it’s not the story of the anti-slavery movement. I think that’s maybe how we tend to think about it, and within that, even tend to emphasize white activism over Black activism. People like William Lloyd Garrison are often on the ‘People You Need to Know’ list, where we can bring forward not just Black abolitionists who were fighting, insisting that slavery must be abolished, but also people who were fighting against racism in their own communities, in their own states in the north. That’s not necessarily on our radar, and I think in some ways that can also ring more closely to our present, because there’s so many similarities. Slavery seems like it has long since gone away, although people have different views on that. But, if that looks like it’s in the rearview mirror, certainly these questions about law enforcement, about equality, about what racial equality should look like in a free society, are very much with us to this day. Jessica Rucker: Thank you. We’re getting some amazing questions in the chat. I see a couple of folks with hands raised; if you wouldn’t mind just throwing your questions in the chat. I’m going to kick it to a question, I’ve got to scroll back up a little bit, Kate, this is for you, “Who’s someone you didn’t know about before you wrote this book who you discovered and who sticks with you?” I love this question. And specifically, if there’s anyone you haven’t mentioned tonight, or someone you want to say more about. Kate Masur: I mean, when I started this book I didn’t really know the whole parameters of the story of Black sailors and how their work lives raise these questions about Black citizenship that the nation struggled with, on and off, for the entire antebellum period and tried to resolve in the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the 14th Amendment. Then I found out about Gilbert Horton, who I had not known about before, but it only took me a while of working with those sources to kind of circle back and realize that he, too, was a sailor. So, let me give you an example which I was kind of looking forward to talking about today. I write, not in depth, about the story of his life, but about a guy named Joseph Thompson, who was a free Black sailor from Massachusetts. And we talk about different ways that people do mobilization and put their agendas out there. Joseph Thompson was an experienced sailor — he had been to France, he’d been all over the place — and he ended up in New Orleans on his ship. He says to the ship’s mate, “I want you to pay me my wages now that we’re in New Orleans, because I might want to go and buy some stuff.” And the mate, for some reason, gets really angry, accuses him of stealing, gets Thompson thrown in jail, and then tries to sell Thompson, who was a free man, into slavery. But Thompson, according to his own account — and he gives an affidavit under oath when he gets back to Massachusetts — he’s like, “Well, I knew some French, so I was able to talk to the French speaking jailer and have him get the word out to some other white people I knew in New Orleans to come and get me out. And they got me out.” He makes his way back to Massachusetts, and he makes this affidavit to a white abolitionist, where he says that this is what happened to him and this is how vulnerable he was just doing his job as a sailor in New Orleans. Also, that while he was in jail he encountered something like a steady stream of free Black sailors from ports like New York, Philadelphia, and Boston, who were making their way into slavery in Louisiana. He’s basically saying, “You guys have to find a way to stop this.” That affidavit gets published in a tract that this white guy named David Lee Child writes, along with a couple of other affidavits from African Americans who are from Massachusetts, attesting to their experiences in southern jails, in having people who they knew incarcerated in southern jails, or they themselves were being incarcerated. Their willingness to speak out also galvanizes, again, they needed white allies — they couldn’t have gotten it done in the legislature without some white allies. But the injustice of it and the amplification of it helps galvanize white people to try to get the Massachusetts legislature to take a stand on this issue and bring it to the federal level, which they finally do in 1839 and into the 1840s. So again, it’s like the courageous mass of people who are willing to speak up and bring it to the people, if they themselves don’t have the platform, get a platform by bringing it to the people who are able to amplify the message and get it out. Thanks for that question. Jessica Rucker: That was a powerful question. I need to shine light on our creativity. Like, why are Black people just so dope? The only reason why I’m free is to get other people free. The reason why I know how to read and write is to teach other people how to read and write. This emancipation, this liberation, can’t just stay with me. The next piece that you just said reminds me of Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi, like the opposite of racist isn’t not racist, it’s being antiracist. It’s a verb. It’s the actions that we take in the name of racial justice. Alright, so I’m checking the time, I’m going to sift through the chat. I see another question as well. “Do you think religious groups and anti-slavery organizations were important in this era?” You talk quite a bit actually in your book about the role of Quakers, and you talk about the AME church and Black Baptists. Say a little bit more about that, please. Kate Masur: Of course. Religious organizations are one of the main ways that many, many Americans — most of whom were Protestant at this time, although there were growing numbers of Catholics in the country — it’s one of the main ways they organize both their spiritual lives and their civic lives. So yes, church organizations were really important here. We see Black churches in the free states, and in the slave states, but in the free states function as community meeting spaces. Once you can have a church, you have a space where you can talk more freely than you could if whites were around. You have a space where you can hold schools, you have a congregation where you can have mutual aid societies and things like that. And Black churches are certainly foundations of the kind of activism that I’m talking about. A lot of white Protestant churches splintered over the question of slavery, including in the north. To give an example, in my research on Chicago I found out that when John Jones originally moved to Chicago, he actually joined a white-led Baptist Church. The white Baptists in Chicago had already gone through a split with the abolitionist Baptists kind of seceding from the main Baptist Church and forming their own abolitionist identified Baptist Church, which was separate from the one that was probably not very pro-slavery but did not want to politicize itself, and get involved in abolitionism. So, church channels were ways that white people also expressed their disagreements and their principles and had really big fights about what kinds of positions to take on these types of issues. Jessica Rucker: We have time for one more quick one so I’m going to the chat. That’s all I can say. Let’s talk a little bit, let’s seal this deal, around white violence. You describe almost how mobs deputized themselves, so to speak, to enforce these anti-Black laws. I want to really say it was literally the legal law, and also the law in terms of the social customs, that the legal system would be anti-Black. I don’t want to censor white people, so please ground your response in how Black people, again, resisted in asserting our humanity during this era. I think this will be our last question. Kate Masur: Okay, thank you for that. So, I’ll just start by saying that the explicitly anti-Black policies of the free states and the slave states sanctioned white vigilante violence. They cast African Americans as outsiders, as people who were vulnerable. They literally made them vulnerable by prohibiting African Americans from testifying in cases involving white people. Sometimes those laws were not enforced, not to the letter or not at all, and yet we see repeatedly. Another example of it is in this large uprising of white people against the Black community of Cincinnati in 1829. They had not been enforcing the registration law that required African Americans to register in Cincinnati. Black people were moving in, there was a substantial Black community, there were Black churches, and then all of a sudden white people started to get antsy, they started to say, “Look, there’s too many Black folks here, let’s start enforcing the law.” And the Cincinnati government says, “We’re going to start enforcing the law, so you better get registered.” This is the summer of 1829. Then before they even begin to enforce it through normal legal channels, the white community rises up and basically riots against the Black community in Cincinnati, leading to about half the community, half the African American population in Cincinnati, leaving permanently — some settle in Canada, some settle in other parts of Ohio. But, to end on a more positive note, and to end with more of what Black people themselves did, the other side of the point is just to think, I found it interesting to think about African American migration northward in this period. We think about the Great Migration a lot, but African Americans were moving from slave states to free states at quite a significant pace, despite these laws that were very unfriendly. And they were demonstrating with their feet that they expected to find a better life for themselves and their families in the free states, however racist the policies might have been. And indeed, I think they did. Without romanticizing how life in the free states would have been for free Black people, there were more opportunities, as I said before, to speak your mind, more opportunities to own land and farm without being disturbed by white people, to form communities, to form churches. I think it also just affords us an opportunity to think about the ways, the continuities perhaps in the ways, that despite conditions that face them, African Americans have pushed forward with a search for both how to find a better life for themselves, their families, and their communities, and also then how to fight back against the situations that they were facing. Jessica Rucker: Kate, this has been amazing to say the very least. I’m just going to have to say thank you. Thank you. Thank you. We want your feedback on this session, the content and the format, and so we’re dropping that link right now in the chat box. But before doing the evaluation, please unmute yourself, turn on your camera, drop something in the chat, but just share your thank you’s to each other for your commitment to your learning and for teaching people’s histories, to our breakout facilitators, to our ASL interpreters, to our tech folks, to all our guests, please. We’ll send you a follow up email with resources that were referenced here today. Now’s the time to unmute yourself, turn on your camera, share some love. Thank you. While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Transcript

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the books, articles, primary documents, and more recommended by the presenters and also by participants.

Lessons and Curricula

|

‘If There Is No Struggle…’: Teaching a People’s History of the Abolition Movement, teaching activity by Bill Bigelow Teaching a People’s History of Abolition and the Civil War, teaching guide edited by Adam Sanchez Who Fought to End Slavery? Meet the Abolitionists, teaching activity by Adam Sanchez, Brady Bennon, Deb Delman, and Jessica Lovaas Reading Between the Lines: An Art Contest Helps Students Imagine the Lives of Runaway Slaves, teaching activity by Thom Thacker and Michael A. Lord |

Related Books and Articles

|

In addition to Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, From the Revolution to Reconstruction, the following books and articles were referenced. Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail by W. Jeffrey Bolster (Harvard University Press). “The Courageous Tale of Jane Johnson, Who Risked Her Freedom for Those Who Helped Her Escape Slavery” by Carrie Hagen. Smithsonian Magazine. “Mary Jane Richardson Jones, Emancipation and Women’s Suffrage Activist” by Jennifer Harbour. National Park Service. “Decades Before the Civil War, Black Activists Organized for Racial Equality” by Kate Masur. Smithsonian Magazine. |

Primary Documents

|

“Letters from a man of colour, on a late bill before the Senate of Pennsylvania,” a pamphlet by James Forten, 1813. Gilder Lehrman Collection. “Missouri Black Soldier to His Daughters, and to the Owner of One of the Daughters,” a letter from Spotswood Rice, 1864. Freedmen and Southern Society Project. “A Freedman Writes His Former Master,” a letter from Jourdan Anderson, 1865. Facing History in The Reconstruction Era and the Fragility of Democracy. “Tearing Up Free Papers” from the The American anti-slavery almanac. 1838. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, NYPL Digital Collections. Illustrations of the American Anti-Slavery Almanac for 1840. Library of Congress. “Address to the Citizens of Ohio,” published in The Palladium of Liberty (December 27, 1843). Colored Conventions Project Digital Records. For many more documents, visit the Colored Conventions Project. |

This Day In History

Participant Reflections

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

Two things: 1) The usefulness of making clear that there was a whole pre-Civil War “rights” movement in addition to just an “anti-slavery/abolition” movement; 2) That each personal story showed how other ordinary people were involved in the struggle to achieve a positive solution.

I think seeing this period as a “movement” — it shifts how you look at the time period.

I am just starting to learn about the civil rights resistance actions in this period and this conversation made me want to keep digging deeper and learning more.

The connection that Jessica made between A) laws that allowed Black people traveling from ‘free’ states to slave states to be enslaved unless proven free and B) D.C. cops questioning her brother outside her apartment is really sticking with me.

The stories of so many individuals that resisted oppression. For example, John Jones and Mary Richardson.

The life of Gilbert Horton was new to me. It will inform how I discuss the free Black community during the Antebellum era.

The specific examples about how the civil rights movement was successful in Ohio to get rid of Black Codes 20 years before the Civil War.

I enjoyed synthesizing this information with what is going on today and other topics taught in history courses. Love the focus on Ohio, given that I like to make history local and I teach in Ohio.

Reconstruction would not have been what it was had there not been such a high level of activism, petitioning, and risk by all the Black people calling for racial equity.

The concept of how petitions gave minorities a way to affect change and how the media (newspapers) played a role in that.

It extended the scope of how I teach/talk about Black resistance throughout history.

Inspiring to learn about the creativity and resilience of African Americans. . . but also heart-crushing. The heroes and heroines that we learned about gave all of us positive energy and respect.

This is a time period important to talk about in light of not just leading up to the Civil War but the discussion of equality vs. abolition and how that survives beyond the Civil War.

The importance of learning and lifting up stories of the Black struggle for freedom.

What will you do with what you learned?

I teach the 1960s Black civil rights movement to my kindergarten class. Now when it comes up, I will discuss that this was one of many civil rights movements that have taken place.

Work it into my current unit. I have pivoted my first unit of government to be centered in Black voices in the founding era and I am excited to add to that.

Share it with other teachers. Incorporate some of the suggested reading into AP English.

I will revise my current civil rights movement class and some names and events from the book.

Make adaptations and additions to current curriculum to continue the integration of anti-racist materials into the euro-centric history curriculum.

Continue to link these stories with stories of resistance, voice, and agency.

I will create a lesson plan based on what I’ve learned.

I have already shared the links and resources with the history and literacy teachers at my school.

Be mindful and purposeful when teaching my unit on the period before the Civil War.

I will share these stories with my students as soon as possible.

I am 1. getting a copy of the book and 2. adding this information to my African American Studies class. We are talking about this period in US history right now.

Will share the information — perhaps suggest our Race Unity Circle facilitate a study of this book. Hope to work on a story of one or more of these characters.

Absolutely use it as part of the narrative that Black people were an essential force in bringing equality to the U.S., and of course, they and allies have a long way to go still.

Teach and encourage the teaching of the early days of the U.S. in a context beyond the lead up to the Civil War.

Have so many resources to add to my curriculum.

Additional Comments

I participated as a mom of two young daughters and someone who is researching the civil rights movement in my hometown, which I never learned about, but which is fascinating. I plan to continue on this path to make this struggle more visible and specifically the role of Black activists, and to engage teachers in my hometown to incorporate this into their instruction. I am also thinking of ways I can work with my school district’s IDEA committee in Nyack, New York, to encourage teachers here to participate in Zinn Education Project sessions.

Thank you for such a wonderful presentation and evening. It was great to hear from Kate Masur. Her mix of scholarly discourse, leavened with powerful anecdotes, was so compelling. What a great teacher! Thank you!

The energy and style of both moderator and presenter were terrific!!! One of the most engaging sessions.

Presenters

Kate Masur is professor of history at Northwestern University where she specializes in the history of race, politics, and law in the nineteenth-century United States. In addition to Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, from the Revolution to Reconstruction, she is the author of An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle over Equality in Washington, D.C. and, with Gregory Downs, The World the Civil War Made. She and Downs are co-editors of the Journal of the Civil War Era, published by University of North Carolina Press.

Jessica A. Rucker is an electives teacher and department chair at Euphemia Lofton Haynes Public Charter High School in Washington, D.C. She is a member of the D.C. Area Educators for Social Justice and was a participant in the 2018 NEH Summer Teacher Institute on the grassroots history of the Civil Rights Movement. She is a native Washingtonian and community accountable scholar with more than a decade and a half of youth development and community education expertise.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn