Calle de los Negros, Los Angeles, 1871. Source: California Historical Society Collection, USC Libraries

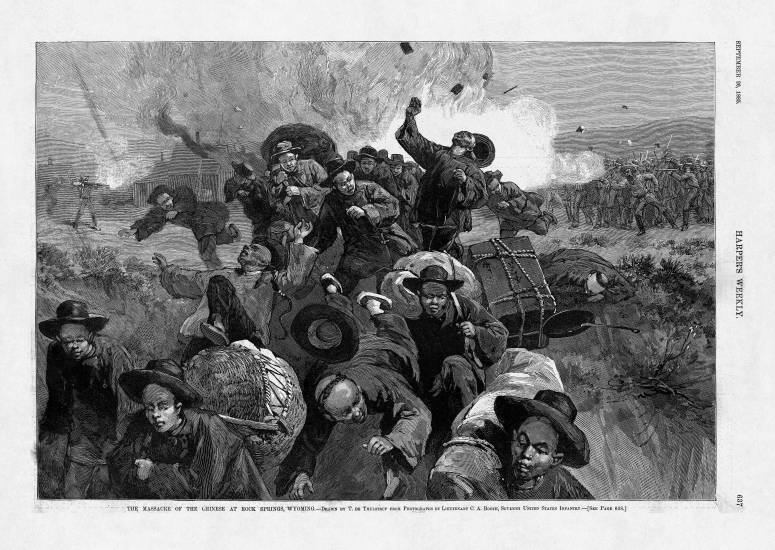

On Oct. 24, 1871, a mob of about 500 Anglo and Latino men rioted in Los Angeles’ Chinatown.

They lynched at least 17 Chinese residents, some as young as 18. This Reconstruction era riot started after a police officer was wounded and a white civilian was killed in the middle of a local dispute. It was one of the largest mass lynchings in U.S. history. The rioters also plundered and destroyed property in the Chinese community.

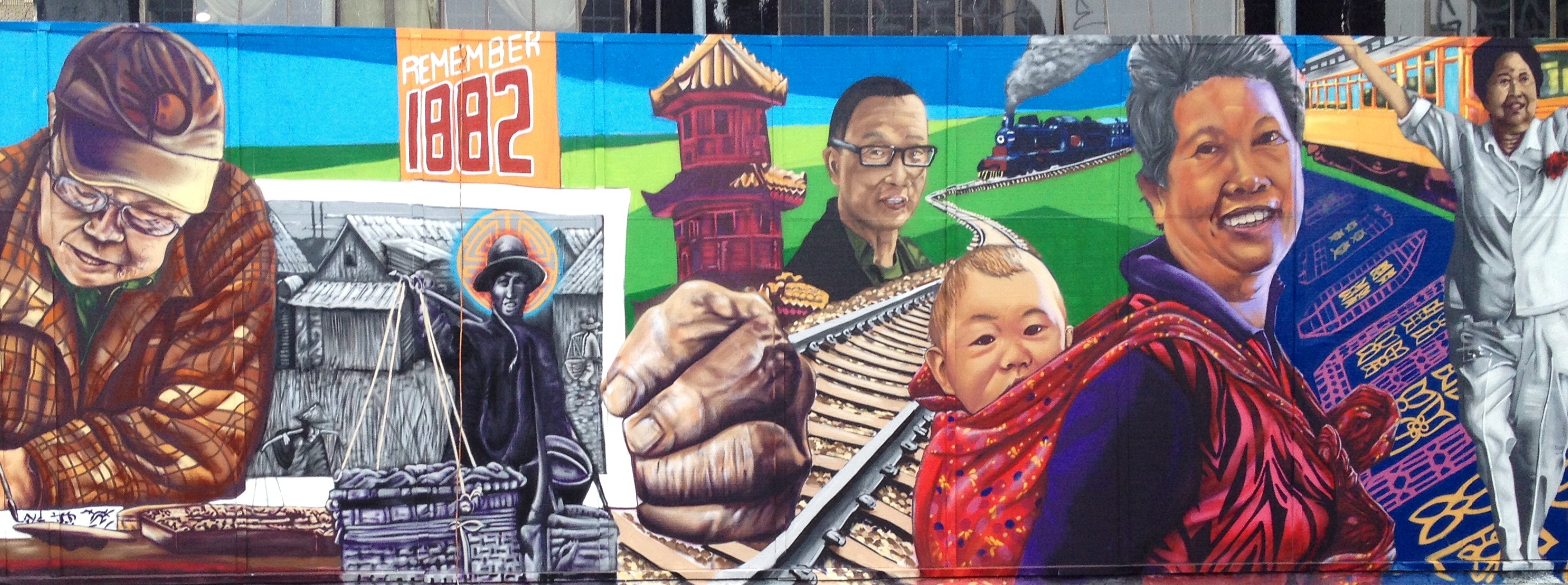

The Chinese Massacre depicted in @JudyBaca’s mural “The Great Wall” as seen in @CraftinAmerica’s video. https://t.co/K8wFIJgauX pic.twitter.com/MMgthQCgW3

— LAhistory (@LAhistory) October 24, 2017

Watch an eight minute documentary about the attack, The Chinese Massacre: One of Los Angeles’ Worst Atrocities, by the KCET Lost LA series.

Here is a description of the massacre from the Los Angeles Public Library by Kelly Wallace:

In October 1871, tensions were running high in Chinatown because of a feud between leaders of two rival Huignan (mutual benefit associations) over the kidnapping of a young Chinese woman. A shootout between several Chinese men broke out in the middle of Negro Alley. The ensuing response by two police officers resulted in the wounding of one of the officers and the death of a civilian who assisted the officers, Robert Thompson. The shooters took cover in the Coronel Building.

Word quickly spread that Chinese residents killed Thompson, a popular former saloon owner. A mob of rioters quickly grew to 500 people, ten percent of the population of the city. The rioters forced the Chinese out of the Coronel Building and dragged the captured Chinese to makeshift gallows at Tomlinson’s corral and Goller’s wagon shop. When John Goller protested that his children were present, a rioter pressed a gun to his face and said, “Dry up, you son of a bitch.” After Goller’s portico crossbar was filled with seven hanging bodies, the crowd dragged three more victims to a nearby freight wagon and hung them from the high side of the wagon. While there are varying accounts of exactly what transpired, there is no disputing the brutality and savagery of that night.

The next morning, seventeen bodies were laid out in the jail yard, grim evidence of the horrific events of the previous night. The eighteenth victim, the first man hanged, had been buried the night before. Ten percent of the Chinese population had been killed. One of the Chinese caught up in the mob violence was the respected Dr. Gene Tong. In fact, of the killed, only one is thought to have participated in the original gunfight.

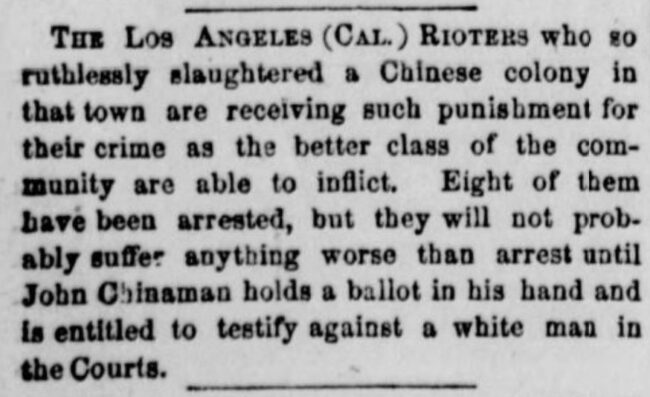

Though a grand jury returned 25 indictments for the murder of the Chinese, only ten men stood trial. Eight rioters were convicted on manslaughter charges, but the charges were overturned on a legal technicality and the defendants were never retried.

At the time, LA’s population was just under 6,000 with about 172 being Chinese. The city’s Chinatown was located on Calle de los Negros, a street that lined a rough, exploited part of the town. Today, it is a major thoroughfare near Union Station, renamed as part of Los Angeles Street in 1877.

Learn More

“How Los Angeles Covered Up the Massacre of 17 Chinese” A detailed narrative of the events of the day at LA Weekly by John Johnson Jr.

“150 years ago, a mob attacked Los Angeles’s Chinese community: To understand U.S. history, remember the full breadth of racist violence” by Reece Jones in The Washington Post (2021).

Reconstruction

The story of the 1871 Los Angeles Chinatown Massacre is included in our national report, Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction. The Reconstruction era gets shortchanged in most state standards. When the era is addressed, there is seldom any reference to Reconstruction beyond the South. As our report notes in the findings, “Telling the story of the history and legacies of Reconstruction in every corner of the country will help teachers make the case to their students that these legacies matter to their lives, no matter where they live.”

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn