By Cierra Kaler-Jones

Bethany Hobbs

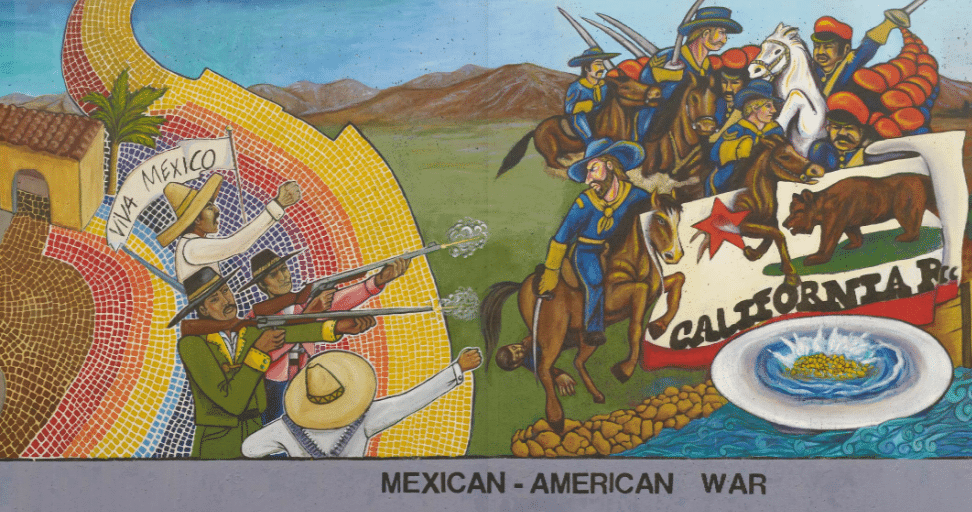

Students were encouraged to read about three figures ― from Mexican cadets like Francisco Márquez to abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison to U.S. political figures like Abraham Lincoln ― in preparation for the virtual meeting. Students from across the region called in by phone and logged into the Zoom platform by video for the one hour class meeting. As students entered the meeting room, Hobbs greeted each person by name, her enthusiasm exuding straight from her home into the various spaces her students called in from. As an educator who employs student-centered learning in her social studies classroom, she wanted to ensure that she was able to transition those same practices to an online format. By utilizing some of the functionalities on Zoom, like screenshare and breakout rooms, Hobbs modeled what a mixer lesson could look like virtually.

To begin, Hobbs invited each figure into the conversation:

Henry David Thoreau, are you here? Could someone share with us some information about him?

Students would then share what they learned from their reading:

I oppose the war because it is not OK to kill Mexican people. I want to disobey the laws and not pay taxes that will fund the war.

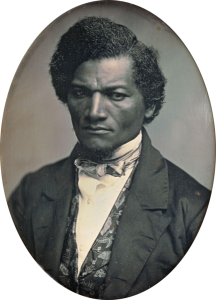

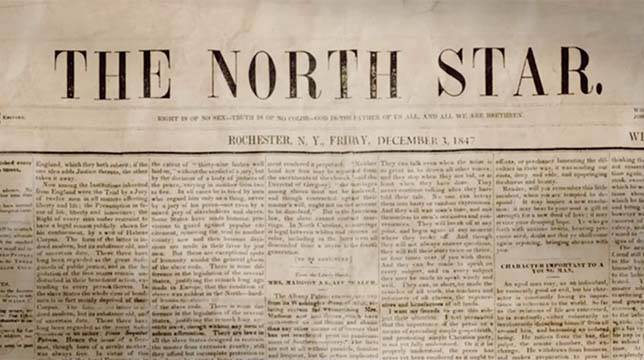

Frederick Douglass

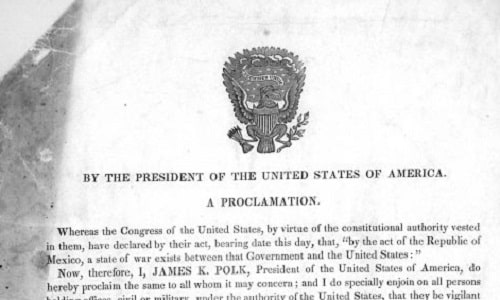

The roles in the lesson highlight the fact that at its heart, the war was about expanding slavery — and the theft of Native land for that expansion. Frederick Douglass’s role says,

This war with Mexico is disgraceful and cruel. . . . Unfortunately, even many Abolitionists (people who are working to end slavery) have continued to pay their taxes and do not to resist this war with enough passion. It’s time that we risk everything for peace.

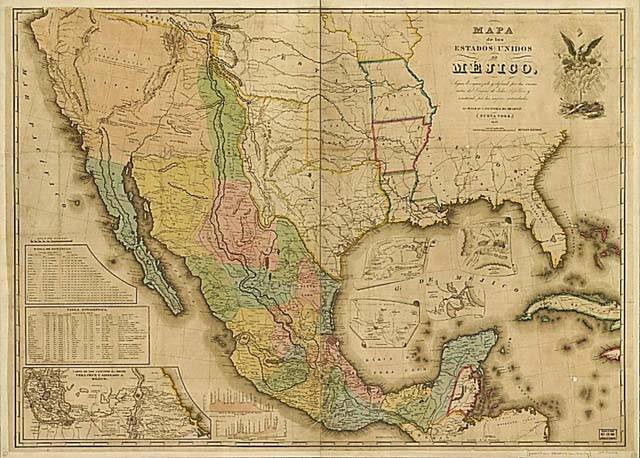

Cochise, a Chiricahua Apache leader, says,

Some of the whites think that my land belongs to the United States. Some think it belongs to Mexico. They are all wrong. My land belongs to my people, the Apaches . . . When I was young I walked all over this country, east and west, and saw no other people than the Apaches. Now the invaders are everywhere. Mexicans, Americans: I want them all gone from my land.

After most of the figures spoke about their perspectives on the war, students were divided into small groups to further discuss what surprised them and why they believed the war occurred. Hobbs used the breakout room option on Zoom to create the small group discussions, which included about five students per room. During this portion of class, students analyzed the war from their personal perspective, stepping out of their roles to debrief some of their wonderings and understandings. Hobbs offered them reflective prompts, such as,

What surprised you about this activity?

Why do you think the United States and Mexico went to war?

What questions does this activity leave you with?

In small groups, students first identified the main points of view and which groups held those perspectives during the war. They named U.S. citizens as a major stakeholder, recognizing that there were groups who opposed the war and groups who were in favor of the war, namely the wealthy, who wanted to gain money and land from the violent conquest. They considered people like Sergeant John Riley, who formally fought on the U.S. side as an Irish immigrant, but switched sides because he saw the brutality and inhumane ways that Mexicans were being treated by the U.S. military. They also detailed how Mexicans and Native Americans were opposed to the war. As an example, María Josefa Martínez, who described her experiences when the U.S. Army seized control of Santa Fe. As a woman, she no longer had the same rights over her property that she did before the U.S. occupation and she feared that U.S. authorities would use the language barrier to confiscate her property.

Some students noted that one piece of history that surprised them was that,

A lot of people became really cruel to others as they were taking land. People took possessions out of people’s houses and just kicked them out. Additionally, I didn’t realize that people got sick because of the bad water and everyone caught diseases and people died from sickness. For a lot of the deaths, it wasn’t even the war itself.

Others related the lesson to other parts of history they learned throughout the school year:

I related this lesson to the fact that throughout history, there were parties within parties that disagreed with each other.

At the end of class, Hobbs played Saint Patrick’s Batallion, written and performed by David Rovics, to provide a creative way to engage students in song before closing for the day. The song is about the immigrants who originally fought for the United States, but switched to fighting with the Mexican people because they saw the U.S. military’s cruelty and the denial of both Catholic and Mexican people’s freedoms. Students filled the chatbox with their sentiments about enjoying the song and its ties to their learning that day,

This is awesome!

This song is dope.

Hobbs and her students show us how we can use online spaces as a mechanism for encouraging students to engage deeply with content while creating space for group discussion and reflection.

Cierra Kaler-Jones is the Education Anew Fellow with Communities for Just Schools Fund and Teaching for Change. She is also a Ph.D. candidate at University of Maryland – College Park studying minority and urban education.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn