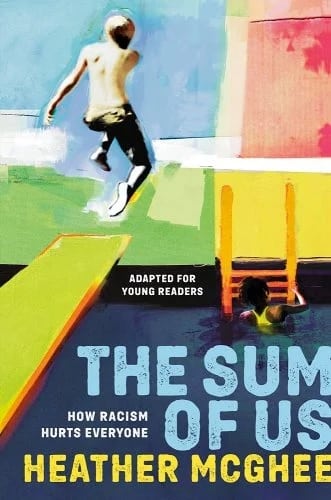

On February 5, 2024, policy advocate Heather McGhee joined Rethinking Schools executive director Cierra Kaler-Jones and Rethinking Schools editor and high school teacher Jesse Hagopian to discuss her book, The Sum of Us: How Racism Hurts Everyone, the young readers’ edition, and the podcast companion series.

Teachers, teacher educators, and school librarians who attended the workshop received free copies of the young readers’ edition of The Sum of Us thanks to a donation by REI Co-op.

This session was the latest in our monthly Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online class series. Don’t miss the rest of the spring lineup — register now.

Participants shared what they learned and the impact of the session:

A wonderful reminder that we all gain more through solidarity.

I learned what McGhee calls the “Solidarity Dividend,” the idea that working across racial lines can yield dividends in the form of economic growth, environmental improvements, and stronger social cohesion. By coming together to fight for policies that benefit the collective, we can overcome the zero-sum game mentality.

Hearing the context of the book from the author’s own mouth is illuminating. Superb presentation.

I learned about the ways in which created racial divides have really hurt what America could be. It is up to us to change for our better, collective future.

I am already familiar with the book, as I have read it twice. I am so encouraged to hear how educators are going to use it in their classrooms!

A reminder that Black Americans are still trying to move through a system that does not want to see us. We still have to prove ourselves, but we know that if people know the real history, there may be some systemic change.

The lie of the zero-sum racial hierarchy and the importance of solidarity amongst all people to fight racism.

I’m still thinking about the comparison between book bans and draining the pools, both as a way to limit access to public goods. A powerful parallel for me to hear.

I think what resonated most with me was the statistic that white high school dropouts make the same or more income than Black individuals with a bachelor’s degree. It increased my desire to teach the importance of education to minorities. It also reminds me how we are all on unequal playing fields.

The more I learn about structural racism and the lies of white supremacy, the more I am determined to learn and teach the truth.

This, like all presentations the Zinn Education Project does, gives me more tools to use in my classroom to educate my students beyond what public education often offers.

Event Recording

Recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: On behalf of the Zinn Education Project, we would like to welcome everybody to our class with Heather McGhee. My name is Jesse Hagopian. I work with the Zinn Education Project, and I’m an editor with Rethinking Schools. I’m joined by my colleague and comrade Cierra Kaler-Jones, executive director of Rethinking Schools and a member of the Zinn Education Project leadership team. So glad to have you here with me tonight, Cierra.

I’m hoping that everybody could add in the chat where you are zooming in from and why you are joining us for this class this evening. We would love to hear who’s in the room and what inspired you to come this evening. I also want to begin by saying happy first day of Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action. It’s so exciting to think about the transformation that’s happening in classrooms and schools and school districts all across the country that are putting forward the four demands of the Black Lives Matter at School movement, and putting forward the 13 Guiding Principles of that movement.

And I also want to say happy Black History Month to everybody. This is an exciting time to be doing this work, and thanks for engaging and linking arms with us in this struggle. So yeah, we hope that your first day went well to all the students and educators out there in the Week of Action.

Some of you are joining us here for this class for the first time, and some of you have participated since we launched this series. It’s really a gift to get to spend this time together with you all, and I want to thank you for being in virtual community with us. Today’s class is hosted by the Zinn Education Project, which is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change as part of our Teaching for Black Lives Campaign. We have members here from our Teaching for Black Lives study groups from all over the country. Thank you all for being here and for your work, engaging with this book week in and week out. If you are in one of the Teaching for Black Lives study groups, please add T4BL after your name.

We also want to let you know that we offer free, downloadable people’s history lessons that many of you have used for middle and high school classrooms from the Zinn Education Project website, including lessons and a report on the Reconstruction era that’s so vital to teach in our classrooms, and is often left out of the history curriculum. Please check out that report and learn more about how you can teach about Reconstruction. I want to turn it over to my co-host, Cierra Kaler-Jones.

Cierra Kaler-Jones: Thanks so much, Jesse, and hello, everyone. Before we begin our conversation today we want to find out who is in the room and go through our plans for our time together. We are posting a quick poll to find out how many teachers, educators, librarians, teacher educators, historians, parents, students, and others are in the room with us. Many of you are in multiple roles, so just pick your primary one. I see a lot of students coming through the chat which is so exciting. I’m so glad that y’all are here. I also see a lot of Milwaukee folks, so shout out to the Milwaukee folks. That is the birthplace and the home base of Rethinking Schools, so it’s always good to be in community with you all.

So, here are also a few quick notes about our format today. The ASL interpretation is provided by Khera Colbert and Tierra Carter — thank you so much for being with us. At the end of the session we ask for your feedback, and we read every word, seriously, we do. And that is where you will request your PD credit. The full recording and the resources listed in the chat will all be sent to you in about a week. We have it so that you can meet each other and talk in small groups to share your thoughts with one another.

Okay, let’s see the results of our poll. It looks like 37% teachers. Thank you so much for all that, you do so much. Love and solidarity to you all! We have 4% K through 12 students. Students are in the room, I love to see it. Three percent family members to students, 22% teacher educators, 1% historians, 1% librarians, and 31% who have identified as other.

So, we’re so glad that you all are here. After about 25 minutes we’ll pause and we’ll be in conversation with one another. But as we move forward we just wanted to have a quick thank you to a donation from REI Co-op so that teachers, teacher educators, school librarians, and curriculum specialists can request free copies of The Sum of Us: How Racism Hurts Everyone, the young adult edition. Alright, Jesse, I’ll pass it off to you so we can start this incredible and exciting conversation.

Hagopian: Yes, thank you, Cierra. I’m really happy to welcome policy advocate Heather McGhee, author of The Sum of Us: How Racism Hurts Everyone, the young readers’ edition of her bestselling book. Welcome, and thank you for joining us.

Heather McGhee: Oh, thank you so much. It’s wonderful to be with you educators, librarians, teachers, students, friends of educators, librarians, teachers, and students. Thank you so much to all the organizations who came together to put this together, including, of course, first to our late breaking donation from REI Co-op, which I just want to shout out, because that meant that we have books that people are going to get, as you mentioned, Cierra. And I’m just super thrilled to have been able to make that happen.

Hagopian: No doubt. Well, this is really special. I’m excited for this conversation, and everyone’s got to buy this book. This is the young readers’ edition, [but] get both and read them both. It’ll be worth your time. Yes, I enjoyed both versions, but I’m really glad you have the young readers’ edition because I think it’ll be awesome for educators in the classroom.

I wanted to start where you started thinking about how you begin the book, by discussing your experiences working for a research and public policy organization and some of the tough lessons you learned from campaigns you worked on there. So, I was hoping you could talk about the experiences you had that helped you develop your ideas about the relationship between race and class in the United States.

McGhee: Well, thanks so much for the question, Jesse. Yeah, I spent nearly 20 years, I think four years as the leader, of a think tank called Desmos — we’re solutions to inequality. So every day I went to work and did research and statistical analysis, advocacy, writing white papers, drafting legislation, and testifying in front of Congress and state houses about the kind of kitchen table economic issues that keep most families up at night. So, why do we not have universal child care, paid family leave, and a well-funded, excellent public school in every single neighborhood? All of these kinds of issues. Why do we have this massive increase in student debt? Why do we have tumbling infrastructure? Why do we have poverty wages? These are the kinds of issues that I was working on.

With my background in law and economics, the idea, the whole setup, was that you would be in this sort of house of study and expertise — a think tank — and you would study these problems, craft evidence-based policy solutions, and then bring them to the halls of power. And whether they were business leaders or politicians, they would make better economic decisions that would make our economy flourish and thrive, and lower economic and security. And it just wasn’t happening. I don’t have to tell anybody on this call, certainly.

I mean, I started writing the book in 2017, so it felt like we were now at that point, almost five decades into what I call the inequality era, where 1% of the population had more wealth than the entire middle class, and less than half of adult workers were paid enough to meet their basic needs. And there just wasn’t enough sense of urgency and problem solving. There was often too much demonization of the kinds of anti-poverty solutions, [even though it] felt like we had the evidence to show that they would be great for the economy.

So I ended up making the unexpected decision to leave my job — it was really my dream job, working as the leader of an organization that I had been hired at as an entry level staffer when I was 22 — and I hit the road. I ultimately would spend three years crisscrossing the country, trying to figure out why it seems like we can’t have nice things in America. And what I discovered was that in so many ways that even I, a Black woman, the descendant of enslaved people on both sides of my family, even I did not realize the extent to which racism in our politics and our policy making was actually driving a lot of the political and economic dynamics that were causing inequality and economic insecurity for everyone.

That was sort of a big Aha!, the big thesis of the book that racism ultimately has a cost for everyone. Of course, because when we think about economics, the largest share of the impoverished and the uninsured are white folks. Even though Americans of color are disproportionately so. And so throughout the book, it’s really a whole bunch of different stories of ways that I uncovered the kind of hidden fingerprints of racism on some of the most vexing public policy issues of our time. And ultimately, it’s a helpful book and it’s been really fun, as you said Jesse, to have this young readers’ version. The paperback just came out two weeks ago, I think, which is great because I’ve gone to over a dozen schools and libraries across the country talking to young people about the book, and it’s been the hopefulness, where we all have a stake in this piece that, they have felt really empowered by.

Hagopian: Yes.

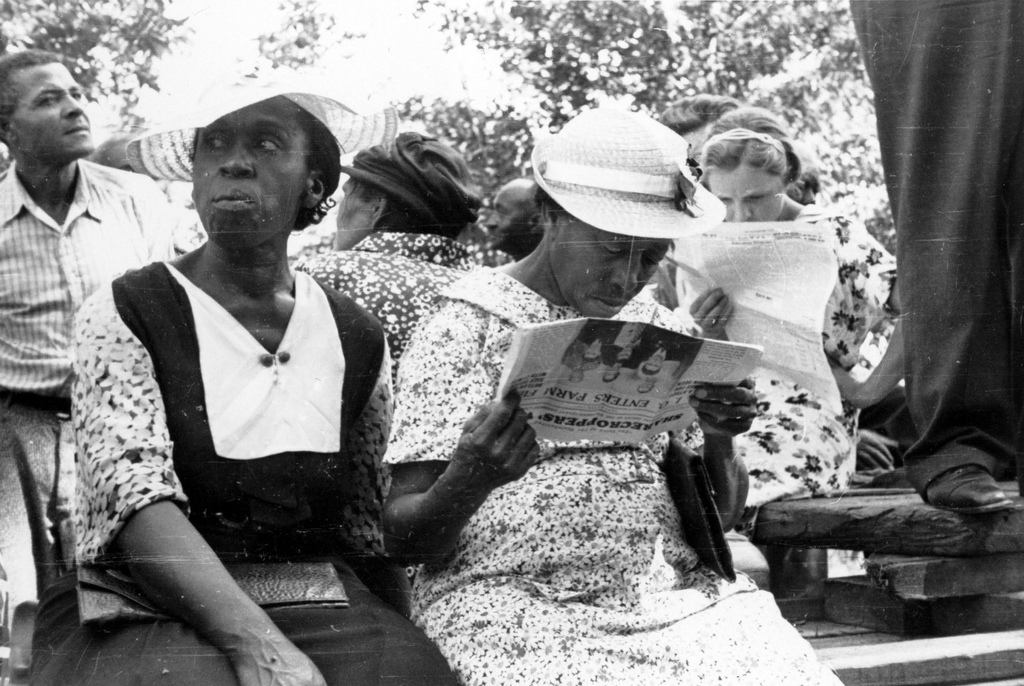

Kaler-Jones: That is so, so interesting and so fascinating! Also, as you talk about in the book — and something that is not new — we see this same sort of lineage being traced all the way from some of this country’s colonial history and the colonial laws and policies that were used to codify racism. You write about this country’s colonial history and how the colonizers work to instill this zero sum hierarchy in the newly created white population in the Americas. Especially important is your discussion of how colonial powers really reacted with new laws to interracial organizing between white indentured servants and Black enslaved people during Bacon’s Rebellion, which is so interesting to me, the fact that these sorts of resistance actions were taking place, and that’s why they created these laws and policies. So can you explain the term zero sum hierarchy, and how that hierarchy manifests in this history?

McGhee: Yes. So, I was looking for what are some of the stories that Americans tell themselves that may stop us from being able to come together to find common solutions to our common problems. And the first big insight that I gleaned on my journey was that there is this big lie, and it’s an old lie. It’s the lie I call this zero sum racial hierarchy. This false story goes that there’s kind of like a fixed pie of well being, and if I get a bigger slice that means that you must get a smaller slice. It’s a story of racial group competition. It’s racialized because, the story goes, if people of color progress, then that must be a threat to white people.

According to a whole bunch of social science, this is a big story in America. And it is a big story that is racialized both because it’s a story of racial competition, and because it is actually more commonly held by white Americans than it is by Americans of color. Generally speaking, we don’t tend to think that our progress has to come at white folks’ expense, but the reverse isn’t true. When I learned about that kind of zero sum story, of course, a zero sum game is one in which there’s no mutual progress. If one player scores a point, the other player loses a point.

When I learned about this zero sum mental model, it really struck me as something that runs absolutely counter to economics. The economics would say that in a flourishing society you want all of your players on the field scoring points for your team. You don’t want anyone sidelined due to debt, discrimination, or disadvantage. Economists at Citigroup calculated that the Black, white economic divide had cost the U.S. GDP — the U.S. economic measurement — 16 trillion dollars over the last 20 years. So inequality is bad for growth. It’s not zero sum, and yet the zero sum lie tells us that we’re not all on the same team.

And so I asked the question, why is it that my white brothers and sisters are so much more likely to view the world through this zero sum lens? It’s not a natural thing. It’s not biological. There is not this sense that there’s some relationship between the melanin content in your skin and your ability to see the world through a zero sum lens. That’s not the way it works, because everything we believe comes from a story we’ve been told. I wanted to say, well, where did this story come from? Who’s telling white Americans this story of zero sum racial competition?

Then I went back into history — and just as you said, Cierra — I found that actually the zero sum story is a very old one that was really created to justify an economic model in our early days, the colonial plantation economic model of stolen land and stolen people and stolen labor. It was used as a real wedge. It was a story marketed by the colonial plantation elite to make sure that the Europeans, who were not part of the elite, would side with their color instead of their class.

As you said, it was really codified into law, the 1705 law in colonial Virginia, which was sort of an anti-insurrection law made after a series of cross racial servant uprisings — the largest of which was Bacon’s Rebellion. The idea was, we’ve got to make a sense of collective identity and group threat around this sort of polyglot European identity which we’re going to form into this new thing called white, and we’re going to make sure that white people are afraid of liberty and justice for Black people. They will feel like it will come at their expense, they will lose their status, they will lose their belongings. It was really always sold by the elite in order to create a color allegiance instead of a class allegiance and break the interracial solidarity that has always been the hallmark of great people’s movements across the world.

Hagopian: I love that. I was just so glad that you went all the way back to the history of how race was invented and showed that it’s this modern invention used to divide and conquer. I really love the powerful metaphor of draining the pool that you developed to help us understand how this divide and conquer works today. So, I wanted to ask you some about the history that helped you create that metaphor. You write about how Southern communities decided that rather than integrate pools, they would close them down altogether, and you talk about how this harmed both communities. So, I was hoping you could tell us more about this history and your powerful metaphor of how draining the pool ends up harming white communities as well.

McGhee: As you can see from the cover of The Sum of Us, both the adult version and young readers’ version, it’s this wonderful piece of art that was created for the cover that is of two kids swimming in a pool. The reason why I chose that as the cover art, as well as the central metaphor, is because I really did, and do, believe that image and metaphor can be very powerful. Which is what I think about most of my time going around the country, giving talks.

What I hope the book does is truly create an education around the relationship between basic classes in this country. What I was able to discover on the course of my journey was this phenomenon that was a real piece of the American landscape that no longer is — which is the bygone, lavishly-funded, grand resort style, public swimming pool. These were the kinds of public swimming pools that could hold thousands of swimmers at a time. They were often built through the New Deal Works Progress Administration. They were a big hallmark of the 1930s and 1940s. There were nearly 2,000 of them in the country, these big public, resort style swimming pools.

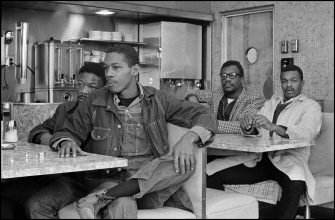

And they were usually segregated. Either under Jim Crow in the South — with a whites only sign on the fence — or just by custom, and enforced through intimidation and violence all over the country. When the Civil Rights Movement empowered Black families and their allies to be able to litigate and sue and say, “It’s our tax dollars that are funding these public pools all along. In the case of the swimming pools, we want our children to be able to swim, too.” And the courts began to side with them. So you began to see this wave of integration orders for things like public swimming pools in the 1950s. I became obsessed with tracking down the stories of what happened when public swimming pools were integrated. So often what ended up happening was that towns and cities would rather drain their public pools rather than integrate them.

In the book I tell the story of going to Montgomery, Alabama, and walking the grounds of what used to be a thousand person swimming pool that was filled in and covered with grass, effective January 1, 1959. Something had happened. Of course, that meant it destroyed a public good rather than have it be shared across the color line. And this was something that happened not just in a place like Montgomery, Alabama, where we think, “Oh, well, it’s Montgomery, Alabama.” But no, it happened in Ohio and New Jersey and West Virginia, in Pasadena, California, in Washington state. Either they would deliberately close it right away, or sometimes they would sell the public swimming pools to a private entity, or lease it for a dollar and then that private entity could then discriminate. The YMCA was actually often a partner for these public pool leaseback schemes.

Or there would be violence around the integration. White mobs, like in St. Louis. The largest swimming pool in America was closed after an all night race riot, a mob that attacked all Black people in sight on the day of the first integrated swim. Then, oftentimes white people would stop going to the pools if Black people started going, and then, when white people stopped going, often the tax dollars would stop flowing and they would stop repairing the pools.

This is a story of the loss of something that was, in many ways for me, this glittering reflection of this deeper economic ethos of the New Deal era. It was for me a helpful way to understand how we went from a country that had not just public swimming pools, but other kinds of economic, public goods — like social security, the big investment in housing stock in the 1930s and 1940s, the GI Bill, the creation of affordable mass home ownership through government policy to create and support and regulate mortgages, high labor standards, wage and hour laws, high collective bargaining principles and enforcement, high levels of taxation plowed back into research and development, free college — all of those things that were really a part of this era of economic public goods, that the public swimming pool is a metaphor. For those were the hallmark of the 1940s and 1950s, and they helped to create a thriving white middle class.

In the book, in the chapter Racism During the Pool, I explain how those economic public goods were just as segregated as the pools, and I go through each and every one and talk about how it excluded Black and Brown families. And leading to the racial wealth gap today, I do have to say that understanding how wealth — not income on your paycheck, but your home equity, your retirement savings, your inheritances, stocks, and bonds, and all of that — that wealth is really how history shows up in your wallet. I have to say for educators on the call, when I explain the way that families are able to pass things on, if your family was able to get some of those public goods in the first half of the twentieth century then your family today is so much wealthier. And that’s really how we can explain the racial wealth divide, which helps young people understand what they see in their communities. When they see the stark differences between neighborhoods of color and white neighborhoods, it really often comes down to wealth, because it can’t be explained by the hard work of people.

Today, a Black college graduate has less wealth on average than a white high school dropout. That’s an amazing fact that helps people understand that it really is about history showing up in your wallet. So that story of the drained pool helps teach the way in which there was a real political shift along the fulcrum of the Civil Rights Movement, where essentially many folks who had really expected government to provide for nice things — provide for the American dream, the picket fence, the great union job, the free college — really turn their backs on that formula once the pool was open to everyone. Once we had a more integrated economy, white Americans, the majority of white voters, turned away from the idea of collective solutions into more individualized solutions. It’s kind of like you build your own backyard swimming pool instead of swimming in the public pool. But it costs more, and of course the whole community loses out on something that they once shared together.

Kaler-Jones: Oh, yes, I love all the examples that you are giving to just remind us all of the ways that this shows up, and how insidious it is. I know, as I was reading the book, just thinking about student loans and how you talked about when the college going population became more diverse that costs started to increase and there was this privatization of public colleges. It’s just so insidious because it’s everywhere. You have a chapter called The Hidden Wound, where you advance an argument that you derive from a book by Wendell Berry. Can you talk about the argument that Berry makes about the hidden wounds of white people, and the similar argument that James Baldwin made as well?

McGhee: Throughout the book I catalog these costs that everybody pays for a society that is organized and still haunted by structural racism. As you said, there’s chapters on the financial crisis, on unions and poverty work, on housing and healthcare and education. It’s mostly the big issues, the big things that families struggle with, the big economic issues. But I had to admit, as I was bringing the book to a close, that there was something else that was more on a personal level — dare I say on a moral or spiritual level — that is a cost that we all pay for racism. That’s what the Hidden Wound chapter is about. And it’s been interesting, when I talk to young people, that’s one of their favorite chapters, as is the chapter Living Apart, which is about segregation., including segregation in public schools.

The Hidden Wound really speaks to the idea that there are psychological and moral wounds that come from believing the lie of white supremacy, the lie of this false hierarchy of human value. There are psychological dynamics that are created in order to deny the extent of racism, in order to figure out a match between the moral code that you may have in your family and as you learn that your race has been a part of this massive injustice. How do you square those things?

One of the more interesting conversations that I tend to have when I’m talking about this chapter is when people really understand — because I try to make this example as much as possible — that when Jim Crow and our racial caste system was the law and spirit and culture of the land in the United States that wasn’t just evil, hood wearing white people who were complacent with it. It’s very important to not create this false dichotomy that says that it’s not easy to be a part of a system that is wholly unjust. So really grappling with that, what do you do with the kind of moral weight of this great injustice, is something I really talk to people about. Most of the book is conversations with people, it’s stories of real people — sometimes I change their names [but] mostly I don’t — who put in their own words what it feels like, for example, to be white in an unjust society, and how they’ve navigated that. So, there are lots of different stories in the chapter The Hidden Wound. At the end I actually talked to faith leaders in a number of different faiths who articulate for me how it is that racism gets in the way of divinity, of salvation, and the oneness with God that all religions are seeking.

Hagopian: Right on. I think we have time for probably one more question before we go to breakout rooms, and then we’ll come back to continue the conversation. But I wanted to ask you about a study that you quote from the Southern Poverty Law Center that examines the curriculum standards in 15 states. The study found that none addressed how the ideology of white supremacy rose to justify the institution of slavery. Most of the standards fail to lay out meaningful requirements for learning about slavery altogether, or about how enslaved people’s labor was essential to the American economy. All of these problems, and this study came out before the wave of laws that are banning teachers’ ability to teach the truth about U.S. history and structural racism.

Connected to that, for decades schools across the country have had an inadequate response to the climate crisis as well, which really threatens students’ lives and the future of this planet. Fossil fuel companies and many politicians and others who oppose climate justice and cheer for inadequate responses, I think, need to be challenged in our curriculum. But, as you write, for them there is a “zero sum competition between the environment and the economy, even a zero sum between the winners of the hierarchy today and those who are just fighting for air.” So what’s the role that the education system plays in perpetuating this zero sum mindset, and in what ways do we need to change the education system?

McGhee: Having written the book before the wave of book bans, the divisive concepts laws, and all of that, it’s bittersweet. It feels like in many ways the concepts in the book around drained pool politics really are very applicable to what’s going on today. So, I think that this strategy is a very hyper-partisan, well organized, and well-funded strategy that is not popular in any state in America. And no state in America is book banning popular with the majority of the population, even though state legislators are able to cram it down. Even though oftentimes it’s just a handful of cranky people attacking educators and reporting them, and all of that challenging books. So, these very unpopular book bans really are a highly partisan, politically elite strategy, to drain the pool of public schools, to say frankly to white parents, be afraid of this integrated public good because your kids are going to come here in this school and they’re going to learn about all of America, and they will be taught to fear their own race, or to feel guilty about their own race. They will be taught empathy towards other races. The research really shows that’s what’s actually being taught when you teach accurate history, you’re developing empathy and critical thinking skills. That creates cross racial solidarity, and that creates unstoppable people power.

Of course, if your ultimate agenda is to keep the economic status quo what it is, to shrink the public sector, to break public sector unions, to not have any need for a tax base, to privatize public schools and profit from them, then this is a great strategy to kind of sow chaos in public schools, and to have financial penalties for teaching integrated stories. It really is something, I think, that unites us all, this horror, this assault on our children’s freedom to learn. But, I will say keep the faith because they really are not popular. It is a massive overreach and it’s very important for us to remember that.

I want to note, at every turn, for every version of this story that I’ve told, I’ve really wanted to create educators’ guides and discussion guides, and I just want to make sure that you have those. There’s an educators’ guide for the young readers’ book. There’s an educators’ guide for the adult version, for a first year common reading experience. There’s the podcast, The Sum of Us, which I made the year after the adult book came out. It’s really all focused on inspiring stories of cross racial solidarity all across the country. And that podcast is free. There are a lot of learners who love to listen to podcasts and you want to bring audio that is available. And there is a companion guide to the podcast that you can find to help educate you and each on the issues. Each of the episodes is a different issue. That is really kind of a great teaching opportunity. So I just want to make sure that before the end of the hour, before we move to breakout sessions, that everyone knows about all of those resources.

Hagopian: Oh, for sure, I love the podcast, and I’m really glad that there is an additional resource, especially for classrooms.

[breakout rooms]

Kaler-Jones: Welcome back, everyone! I hope you had rich discussions. We’d love to hear what you discuss in your breakout session, so please share in the chat, shout out your group, share highlights from your discussion. [. . .] I’ll kick it over to my comrade, Jesse.

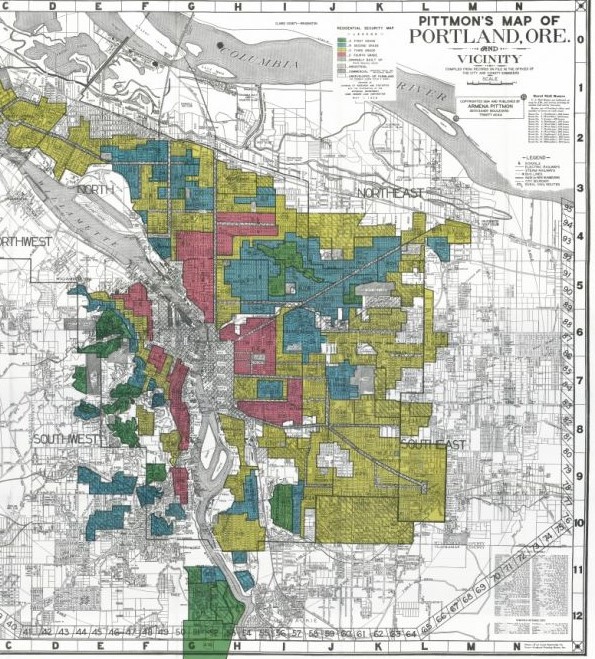

Hagopian: Thank you, Cierra. One way to support teachers in bringing this history to the classroom is with our Teaching for Black Lives study groups that we have all over the country. We have more than a hundred groups this year. You can see some of them on this map and many members and leaders of those groups are in this session with us today.

We also participate in the Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action which begins today. For the Week of Action, some educators do a lesson for one day, others all week, and some do school wide activities or even district wide activities. I’ve got to tell you, I’m extremely excited. After this call in Seattle we have a family history project where youth are going to interview their family about their own history. At the end of the week we have the young, gifted, and Black student talent showcase to celebrate this Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action.

But I want to now let you know that two educator guests will share a quick story about how they engage students in the Week of Action, one school wide and the other in her classroom. They were both presenters at the DC Area Educators for Social Justice Black Lives Matter at School Curriculum Fair. First, I’m happy to welcome Dr. Tamyka Morant, assistant principal at Bruce-Monroe Elementary School at Parkview, a DC Public School, where the whole school participates and engages families, too. So welcome, Tamyka. I just wanted to ask you, why does your school engage in Black Lives Matter at School’s Week of Action?

Morant: Our school has committed to cultivating a learning environment that is grounded in antiracism, equity, and justice, and we understand these as learned, actionable behaviors. Thus, we see our entire school community as learners striving to be agents of change, that intentionally disrupt racist, oppressive practices and replace them with opportunities for freedom, liberation, and joy. And Black Lives Matter at School helps us meet that goal.

Hagopian: Yes, thank you. Incredible to see your youth, just very inspiring. Please tell us how you make Black Lives Matter at School a school wide endeavor.

Morant: Each grade from ECE through 5th grade studies a different Black Lives Matter at School principal for about 6 to 8 weeks. They design a complimentary take action project and then present the learning of their action to an audience of other students, families, and community partners in what we call a Black Lives Matter at School Marketplace of Knowledge. It’s just a great time for students to show their work and their learning, and each grade does a different one, so by the time the students graduate they would have done all of the principles.

Hagopian: Wow, incredible! Thank you for that. I know many are inspired here, and I hope to see stories more across the country like yours, and to learn more about what goes on this year. Cierra, you want to also jump in?

Kaler-Jones: Sure, I think we have one more question. “I understand this year you connected to the theme of collective value through math. So can you give us one example of how you did that?”

Morant: All of our students, ECE through 5th grade, work in teams for 6 to 8 weeks to design a math game based on math game design theory. And all our students compete in a math trivia tournament to score points based on a teamwork rubric. We call this [illegible], it’s mathematics and community together.

Hagopian: Beautiful.

Kaler-Jones: I love that. Thank you so much, Dr. Tamyka. We appreciate you and this work. Next, I’d like to introduce Amber Bennett Foote, an 8th grade teacher in Prince George’s County, Maryland, with more than 21 years of experience teaching English and U.S. history. Shout out to the DC Area Educators for Social Justice group, shout out to teachers in the DMV. I know that you teach for Black lives all year long, but please tell us one example of what you’ve done in the past, or this year, for the Week of Action.

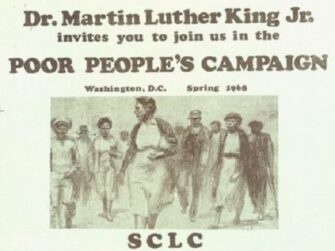

Amber Bennett Foote: Well, currently, my classes are focused on the principle of being unapologetically Black, and also empathy. And particularly the idea of loving and desiring freedom and justice for ourselves within those themes. But I’m in a school that has had no school wide program to commemorate, or even an utterance of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. whatsoever. However, in my class, that’s not going to happen. We focused on Dr. Martin Luther King’s Poor People’s Campaign and his organizing efforts with the sanitation workers strike in Memphis, Tennessee. From that we admired the demonstration of Resurrection City, which happened right on the National Mall in 1968, as a bold demonstration to push Congress to prioritize eliminating poverty. And we compared Dr. Martin Luther King’s speech to the 2nd Bill of Rights, or the Economic Bill of Rights, as proposed by former President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. We close out the unit by having students research local organizations, services, and campaigns. We’ve also come off of Bacon’s Rebellion and discussing the racism of real economic issues and so forth. So it’s a lot.

But we closed out the unit by having the students facilitate a SNCC styled seminar. Borrowing from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s determination to have democratic voice, we decided that every student has the attention of the circle for 1 minute on each agenda item that they choose. And if they choose not to speak, we will observe 30 seconds of silence and encouragement to shout out to the student anyway for the voice that we hope to emerge. I asked the students two questions after my presentation last week, and that was simply what is economic justice to you, in a sentence? And we’re building a collage around that. Also they finished the sentence, “In a humanitarian world with economic justice for all ___.” They gave something you would experience and witness, and they really got pumped up, especially after hearing one of the speeches by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. They mock some speeches and so forth, but they really spoke to some of the things that they wish they could reimagine and see, and what they do see as an economic injustice.

Hagopian: Right on. That’s awesome. Very proud of him.

Kaler-Jones: Thank you so much. And I love the SNCC style seminar. I think earlier in the photos I saw a picture with Miss Judy Richardson, SNCC veteran and documentary filmmaker, with a shout out in the chat to check out the SNCC Legacy Project. That’s so inspiring. Thank you so much, Amber, thank you so much, Dr. Tamyka, for joining us and for sharing about the work that you’re doing, not just for the Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action, but the year of purpose and the lifetime of practice. We appreciate you.

Foote: Thank you.

Hagopian: Yeah. I loved seeing you doing that work around the Poor People’s Campaign. I just got back from Memphis, visiting the Civil Rights Museum there and getting to be in this place where I had studied about that campaign and the sanitation workers was really transformative for my understanding. So I appreciate you.

Foote: Thank you

Kaler-Jones: Well, we are going to head back into the conversation. As we move forward in the conversation, one thing that really stuck out to Jesse and I was the idea of the solidarity dividend to describe Americans working across racial lines, to struggle for the common good, and achieving better lives for us all. So, can you share with us some examples from the people that you talked to around the country?

McGhee: Absolutely. And that was a great pithy definition of solidarity dividends. I appreciate that. So, basically, there are three important concepts in the book, the zero sum racial hierarchy, the drain the pool politics, and then the solidarity dividend. The solidarity dividend is exactly this idea that we can really gain things, real gains, dividends that we can unlock, but only through the power of collective action. And in our diverse country, where racism has so often been used to divide working and middle class people from one another, to stop us from swimming in the same pool, it really takes multiracial solidarity and cross racial solidarity. So, the tenth chapter of the book is called Solidarity Dividend, and it tells some stories of really unexpected folks realizing that they have more in common than they have that keeps them apart, and that they have more power together than they do on their own.

Then, because deadlines are deadlines, I really felt like when I was writing the book that I wanted more stories of solidarity dividends than I was even able to get into the book. The sort of big story, the memorable story in the book, is about a town which unfortunately has been added to the list of towns whose names are synonymous with mass shootings. It’s a town called Lewiston, Maine, that very recently experienced a horrendous mass shooting. It’s a town where I spend a lot of time, because it’s a town that has been revitalized by the presence of people very unlike the folks who’ve lived there for the past one hundred or so years, it’s African, Muslim, mostly refugees and immigrants who have helped to revitalize this white town in rural Maine. I tell that story in the book.

But the podcast is actually exclusively stories of solidarity. I really wanted to go back out on the road and collect more stories of cross racial organizing, and so each of the episodes in the podcast takes place in a different place in the country, like Memphis, rural Nevada, small town Maine, Kansas City, and others. [Each podcast episode] tells a story of some problem in their community that has its roots in racism, even if it’s not obvious. It tells a hopeful story of a victory of people coming together across race to solve it. One of my favorite stories is the first episode. Actually, there’s a prologue episode that’s just about the pools and kind of setting up the themes of the podcast, but the first full length episode is about Memphis and it’s about an historic campaign that united Black and white Memphis — a very, very segregated city, the place where Martin Luther King was assassinated. It was this amazing, unlikely campaign to deal with environmental injustice and sacrifice zones that Black Memphis had become, highly polluted. But there was a big oil pipeline that was threatening to run through Black Memphis, but also threaten the entire city’s natural drinking water. And it was this amazing cross racial campaign, and the leader of the campaign was a young brother named Justin J. Pearson, who you can hear talking in the podcast. He’s kind of one of the stars of the story.

About a year after the podcast came out he ended up running for the state legislature, and then when another mass shooting happened in Tennessee, he and two other state senators helped and supported the parents and teachers and students who were protesting in the State Capitol. The right wing legislature in Tennessee just went hard on those three, the two Justin’s especially. He became sort of a sensation overnight, because it was unbelievable the way in which they tried to silence him. He’s just an extraordinary young man and an extraordinary leader, and I feel very proud that I got to know him early on in his career. I got to know him because he read the book and talked about the solidarity dividend at the rallies three years ago to block the pipeline.

Hagopian: Oh, that’s so cool. That’s great. And it’s amazing to see how unions can be part of the struggle for that solidarity dividend in different eras of U.S. history. We’re now seeing a resurgence of the labor movement in some really exciting ways, like the UAW or the Amazon Labor Union. I’m in Seattle, so the Starbucks organizing has been really important here. But you interviewed several union workers and looked at the ways that racism weakens unions for all workers. So, I was hoping you could talk more about the importance of the labor movement and how it’s been intentionally stunted by those who know the power of racism to divide and conquer.

And your Sum of Us podcast gives a lot of these powerful examples, as you’ve been sharing about the power of working class people to reach across those divides of race or religion. More so, I thought it’d be cool to play a little segment of the podcast and get you to respond to this story and tell us more about it.

This was the first time in my life I had seen so many people of so many different backgrounds in the same room. And at that point, even before anyone got up and spoke or anything, I kind of felt this shift in my mindset where I suddenly became the person who said, “We need this everywhere.” Bridget, like many Americans, especially white Americans, had bought into the lie of the zero sum racial hierarchy, the idea that there’s a ladder of human value, and a dollar more in a Brown or Black person’s pocket must mean a dollar less in hers. But this first meeting opened Bridget’s eyes to a different story about our country.

So I don’t know if you want to comment on Bridget’s story?

McGhee: There’s a chapter in the book called No One Fights Alone, and it tells some labor history which I’d love to have the chance to tell. I all the time shout out to people’s history, and just really how important it is and how under-resourced labor history is. So, I’ll tell you a little bit of labor history, because I try not to take for granted the idea that my readers even know what a union is. I just really try to make it plain. What is the core idea that people can come together, and by having all of the workers, or a majority of workers, ask for the same thing they can have more leverage with the boss.

Then I tell a story of the heartbreaking loss of a union drive, a failed union drive in Mississippi from 2017, where racism really stopped the workers from being willing to organize and vote in a UAW contract, a UAW union, for representation. I talk about the very explicit ways in which race showed up in that campaign as well as the ways in which racism sort of stymied the labor movement throughout its history. It’s basically this: unions, like government, are this form of collective action for working people. And so drained pool politics impacted white support for labor unions as well, although since the book came out there’s actually been more of an increase in support across racial groups for labor unions, although there’s usually a difference. People of color are generally more supportive than are white folks.

But then I tell a hopeful story. And that’s the story, not of factory workers at an auto plant in Mississippi, but the story of folks flipping burgers and working fast food in Kansas City. That’s the story that you just heard a clip from. It’s actually the one story in the podcast that is the same as the book. Because Bridget and parents are just amazing characters and I really wanted to be able to tell that story twice. It’s a story of working class folks. Bridget is a white woman who really, as I said in the clip, had racist ideas, anti-immigrant ideas, and it was only through organizing for $15 an hour and a union that she began to really create that kind of cross racial empathy and understand that she needed Black and white and Brown workers to come together to be able to win and to be able to affect her life. She’s a very articulate spokesperson for the need for white working class consciousness to shift in order to reject zero sum thinking and understand the power of collective action and cross racial solidarity.

Hagopian: Yeah, I’m so glad you have those specific examples because I’m always like “racism hurts everybody,” but when you can show it and tell the story and hear the voice of the person who figured that out — the voice of a white person who figures it out — then you can actually change people’s minds and educate young people. So thank you.

Kaler-Jones: Yes, and to Jesse’s point, you write that white people are the most segregated people in America. So what are some of the costs of continuing to segregate, and what are the benefits of integration, both culturally and economically?

McGhee: Yeah, as I mentioned, Living Apart, the chapter on segregation, is one of the most popular ones with young people. Because, if you think about it, that’s their lives, right? Generally speaking, we are still highly segregated. White people are the most segregated, the least likely to live with folks of any other race. But in general, our cultural landscape is quite integrated. But all young people know is that their neighborhoods are not and their schools are not. And so that’s one of the big head scratchers that young people have; it’s like, why is it this way? And so, in Living Apart, I tell the history of how the government segregated America. It’s a really condensed version of Richard Rothstein’s Color of Law, and then talk about it from the perspective of young people. There’s some characters in the chapter The Same Sky who are young folks, who are white kids who go to integrated schools and really see that as a positive good. And the parents who have to jump through hoops, white parents, to not just be funneled into the white “good schools,” but actually be in a global majority school.

And so, the costs of segregation are environmental. As I talk about in the same chapter, which is about environmental racism, which was brought to life in the Justin Pearson in Memphis episode in the podcast. Because it’s much easier to pollute a segregated community than it is an integrated community. The costs of segregation are fiscal. There was a landmark study in Chicago that counted up in the billions of dollars in terms of crime, housing costs, lost lives, lost economic potential, because of the tremendous levels of segregation. [illegible] The benefits to white students of integrated schools, the benefits to everyone of integrated education, in integrated neighborhoods. That’s a chapter, Living Apart, that really just focuses squarely on the most visceral experience we have of the legacy of racism.

Hagopian: Yeah, what an awesome conversation we’ve had! I just have one more question, and we just have one more minute. But I wanted to be sure that we get to the teaching ideas around this book. So, I wanted to ask you what ideas you would offer for teachers on the call here to teach this important history and its connection to the present so that people can see how this history impacts the way we’re living today. Or, what message do you have for teachers about their roles at this time?

McGhee: Well, in closing, I want to say thank you to Cierra and Jesse, to our ASL interpreters who have been wonderful, and to all of you, the 300 of you still on the line at 8:30 at night on east coast time. Thank you so much. Obviously, throughout the conversation we’ve been tossing resources left and right, but ultimately I hope I’ve made it clear that my dream for this book, for the adult version — and then it was beyond the fantasy for there to be a young readers’ book — but my dream for this whole project, with The Sum of Us, was for people to read it in groups, for it to be the kind of book that I wish that I had when I was growing up. I was trying to make sense of our society and politics and the dynamics, the often very racialized dynamics, that I heard in our public discourse and the inequalities that I saw from neighborhood to neighborhood. I wanted this to be a book that helps explain so much of what puzzles any American. That’s why the opening lines are, “You ever wondered why we can’t seem to have nice things?”

I didn’t want this to be a book for people who studied economics, or a book for people for whom it’s their 50th book they’ve read on race and racism. I wanted this to be an entry level book for people to understand how we got this way. There is history in every chapter. I think we know where we are today, but we have to understand the steps we took to get here. It’s really a book about the present, and more importantly, about the future. And it’s dedicated to my son and to the young people who will be part of remaking the society with him.

I’m just in deep awe and respect for educators, now more than ever, who are under attack, under-resourced, under siege, but also have the joy of working with the most diverse generation in American history, who have high levels of civic engagement and high levels of of awareness about all of these issues and are just really ready for the kinds of tools that will empower them. In closing, the thing that I keep getting back from students and from librarians and educators is that so often the discourse around racism can be depressing. Of course it is, but young people have got enough to be depressed about and anxious about. But I did write the book to be hopeful, and that is something that I hope can be a way to get beyond the political posturing and all of that and just realize that this is a book to give young people — Black, white, and Brown — hope for a shared future.

Hagopian: Beautiful. So well said, and it did give me hope. I mean, they have billions of dollars to increase inequality and promote their agenda, and we have billions of people, but only if we can overcome divisions like racism. Your book really helps us think about the fact that we can win, that we can create the society we want, if we’re able to forthrightly confront racism. So, I can’t thank you enough for writing this, for doing the research, for taking your time tonight with us to share with educators. You think about the 400 educators that were on here, and the thousands of students that they’re going to reach, and that’s really exciting. Have a great evening, everybody.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Audiogram

In this audiogram, Heather McGhee discusses the costs of segregation, past and present, and the benefits of the interracial organizing that opposes it.

Resources

Many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants.

Lessons

We offer lessons that can accompany select chapters of The Sum of Us young readers’ edition.

Books and Articles

| In addition to The Sum of Us: How Racism Hurts Everyone, the following books and articles were referenced.

Be a Revolution: How Everyday People Are Fighting Oppression and Changing the World–And How You Can, Too by Ijeoma Oluo (HarperOne) The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America by Richard Rothstein (Liveright) The Hidden Wound by Wendell Berry (Counterpoint LLC) The Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated the United States by Richard Rothstein (from the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series) Remembering Red Summer — Which Textbooks Seem Eager to Forget by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (from the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series) Ableism Enables All Forms of Inequity and Hampers All Liberation Efforts by George Yancy (Truthout) |

Audio and Video

|

The Sum of Us podcast Segregated by Design, film directed by Mark Lopez and written by Mark Lopez and Richard Rothstein |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in People’s History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keywords.

|

Jan. 5, 1931: Lemon Grove Incident April 3, 1934: Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union Jan. 25, 1941: A. Philip Randolph and March on Washington June 22, 1944: GI Bill Signed Oct. 17, 1950: Empire Zinc Strike Dec. 20, 1956: Montgomery Bus Boycott Prevails Feb. 1, 1960: The Greensboro Sit-in Begins Feb. 3, 1964: New York City School Children Boycott School June 18, 1964: St. Augustine Swim-In April 11, 1968: Fair Housing Act Signed Into Law May 12, 1968: The Poor People’s Campaign Began Oct. 29, 1969: Supreme Court Rules Schools Must Desegregate June 11, 2002: African American Residents in Louisiana Win Their Fight Against Shell Oil Nov. 6, 2011: Keystone XL Pipeline Protest at White House Dec. 6, 2013: First Nations Water Warriors Block Fracking April 1, 2016: Standing Rock Sioux Oppose the Dakota Access Pipeline July 2, 2021: Opposition Prevents Byhalia Pipeline Construction |

Additional Video Clips from the Session

|

Discussion of colonial laws and Bacon’s Rebellion. |

Discussion of a clip from McGhee’s podcast The Sum of Us on labor organizing. |

Participant Reflections

With more than 400 attendees present, the conversation and chat was lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Polls showed participants included 37% K–12 teachers and 22% teacher educators, with students, historians, librarians, and more also present.

This class coincided with the first day of the Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action. To kick it off, two educators and presenters at the DCAESJ Black Lives Matter at School Curriculum Fair shared stories about how they engaged students in the Week of Action.

Dr. Tamyka S. Morant, an assistant principal at Bruce-Monroe Elementary School, a D.C. public school, spoke of “cultivating a learning environment that is grounded in antiracism, equity, and justice” and how Black Lives Matter at School helps her and her students achieve that. Amber Bennett Foote, an 8th-grade English and U.S. history teacher in Prince George’s County, Maryland, talked about how her classes are focused on “the principle of being ‘unapologetically Black.’”

See below for more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

The historical impact of generational wealth, or the lack thereof.

The statement about “wealth is how history shows up in your wallet” was very thought provoking.

The closing of public pools [then] has a connection to the closing of public schools [today].

I learned that racism doesn’t harm just Black and Brown people, but everyone. The people with billions of dollars want us to turn against one another so we don’t work together against them.

Working to disrupt the zero-sum train of thought is the most important thought that was impressed upon me.

The metaphor of draining the pool is a powerful way of describing how white people motivated by racism have destroyed public goods.

There are so many resources that will be so helpful to teach this to young people. The idea of zero-sum gains runs counter to economics for the masses. The idea that all this started due to rebellions during the colonial era, like with Bacon’s Rebellion, is mind-blowing. I saw the connection when Heather McGhee mentioned it but had not seen it as such before.

Love the solidarity dividend discussion; it makes me feel like we can all have a role in improving conditions for all people.

I don’t think I’ve ever explicitly taught and discussed with students how racism affects white people. I need to think more about what that means in a 5th grade classroom. I am inspired!

What will you do with what you learned?

I incorporate environmental racism into my teaching about environmental sustainability, but this dialogue showed much potential for me to do more.

I want to incorporate The Sum of Us concepts as a theme in my 11th grade U.S. history courses.

As a teacher I feel more equipped to provide the background and basis for many of the topics around racism that come up among students and staff.

I already use the adult version of the book; I’m excited to bring the young readers’ version into my curriculum to make it more accessible to a larger audience.

I would like to integrate the [Black Lives Matter at School] 13 Guiding Principles and parts of The Sum of Us in my multicultural course next trimester.

I will continue to use my voice to educate, elevate, and encourage my students to listen, explore, and ask questions about our past history and how this moves and pushes us forward to find our place in this society. I will also explore Heather’s podcast, which I haven’t done yet.

I am planning to host a book study group with teachers and family members and then use that session to help us decide how to integrate this book into our socio-cultural competence curriculum.

I will use passages from Heather McGhee’s book to model for my students effective academic writing, effective research, and effective argumentation.

I teach 2nd grade. My goal is to provide a foundation for true history based not only on injustices, but how people have worked to disrupt them. I want to develop skills of empathy and critical thinking so students will ask questions about the world and think of ways to change it.

Presenters

Heather McGhee is distinguished lecturer of urban studies at CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies. Her best-selling book, The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together, was adapted into a young adult readers’ version and has a podcast companion series. In addition to testifying before Congress, drafting legislation, and developing strategies for organizations and campaigns, McGhee is chair of the board of Color of Change.

Cierra Kaler-Jones serves as the first executive director of Rethinking Schools. Cierra is also on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project, which Rethinking Schools coordinates with Teaching for Change, and has hosted many of our Teach the Black Freedom Struggle classes. Cierra is a teacher, a dancer, a writer, and a researcher. She previously served as director of storytelling at the Communities for Just Schools Fund.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, and on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn