By Adam Wasserman

Most Black Seminole historians have accounted for the “Negro Fort” and the towns on the Suwannee River in the second decade of the nineteenth century, but until recently an equally substantial settlement that formed in southwest Florida had gone all but ignored. Some of the first Africans arrived to the region as early as 1770s and 1780s, amidst the War of Independence. In the first two decades of the nineteenth century, each act of American aggression brought new and larger waves of Black and Seminole refugees. The first wave occurred amidst the Patriot invasion on Bowlegs’ and Payne’s towns in the Seminole capital of Alachua. In January 1813, shortly before the Patriots made the final assault on Alachua, Creek Agent Benjamin Hawkins reported that the Seminoles and Blacks were already retreating to southwest Florida in advance:

I received from an Indian of note . . . the following information . . . Paine is dead of his wounds . . . the warring Indians have quit this settlement, and gone down to Tellaugue Chapcopopeau, a creek which enters the ocean south of Moscheto river, at a place called the Fishery. Such of their stock as they could command have been driven in that direction, and the negroes were going the same way. The lands beyond the creek towards Florida point, were, for a considerable distance, open savannas, with ponds; and, still beyond the land, stony, to the point.¹

Hawkins later reported: “The negroes now separated and at a distance from the Indians on the Hammocks or the Hammoc not far from Tampa bay,” after they fled the Patriot invasion. More specifically, Hawkins was alluding to the Peace River where it flows into Charlotte Harbor near present-day Punta Gorda. “Tellaugue Chapcopopeu” was the Creek town of Talakchopco located on the main crossing point of the Peace River, present-day Fort Meade in Polk County. The “Fishery” Hawkins mentioned was Charlotte Harbor where one of the six Cuban ranchos on the southwest coast was established. Two hundred men operated these sites during the fishing season from November to April — a multiethnic conglomeration of Spanish, Seminoles, Creeks, and Black Seminoles. For years, many natives from all across the Southeast would travel down to southwest Florida during the winter to these plentiful hunting grounds and exchange deerskins and other crafted items for trade goods with the ranchos. The Seminoles were part of this movement and profited by servicing parties passing into and out of the hunting grounds at Talakchopco. It was likely that their Black maroon allies were familiar with the location as well. After the destruction of their towns in Alachua, Talakchopco served as a primary area of refuge and relief for the destitute Seminoles and Red Sticks, while their Black allies established themselves in a separate location to the north.²

The second wave came with the attack on Prospect Bluff. In 1815, after Nichols left the “Negro Fort,” some of the Blacks no longer felt secure in the absence of the British military. Woodbine left the “Negro Fort” with about eighty Blacks who relocated to the region for safety. John Forbes & Company complain of their runaway slaves having left the area to both Tampa Bay and the Suwannee River after the fort’s destruction. John Forbes went down to Tampa Bay to look for these fugitives and found that they were settled around Charlotte Harbor. This community was referred to as “Angola” by Cuban fisherman and became the last remaining stronghold for the Black maroons in Florida after Jackson’s invasion. Its precise location was close to the Oyster River (present-day Manatee River), a tributary of Sarasota Bay, near Sarasota. In 1821, a South Florida Expeditionary mapped out the region. The map chart was entitled: “A draft of Sarrazota, or Runaway Negro Plantations.”³

The third refugee wave came with Jackson’s assault on Miccosukee and the Suwannee. With Jackson’s destruction of Black and native power in northern Florida, various Black, Seminole, Red Stick, and Spanish settlements were established on the southwest Florida coast, stretching from Tampa Bay down to the Peace River. Red Stick leader Peter McQueen and his followers found refuge at Talakchopco. His ally chief Opponey established himself to the north at Lake Hancock, where the Peace River originates, and his Black followers to the southeast at the town of Minatti. Following Jackson’s assault on Suwannee, an 1819 report observed that “the negroes of Sahwanne fled with the Indians of Bowleg’s Town toward Chuckachatte” north of Tampa Bay.4 Captain James Gadsden, aide to Jackson in his Florida campaign, reported back to Jackson about the importance of establishing Tampa Bay as a maritime depot:

It is the last rallying spot of the disaffected negroes and Indians and the only favorable point from whence a communication can be had with Spanish and European emissaries. Nichols it is reported has an establishment in that neighborhood and the negroes and Indians driven from Micosukey and Suwaney towns have directed their march to that quarter.5

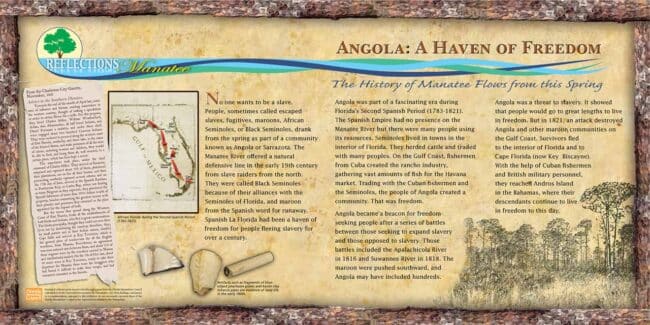

A heritage interpretation sign for Reflections of Manatee at Angola, created by the Florida Humanities Council in 2014.

At its height, Angola’s population grew to become one of the largest maroon towns in the history of Florida. The accounts of the Creek raid on Angola, which recorded the combined number of refugees with enslaved captives, suggest that its population numbered at least around nine hundred at the time of its destruction. Angola was desirable for more than its distance. The Manatee River was an optimal site for trading with Havana and Bahamas merchants. Its proximity to the Spanish ranchos ensured that the Blacks would have access to foreign markets for their agricultural goods, fish, and timber, which, in turn, provided Blacks and Seminoles with arms and powder. Besides the fishing ranchos at Tampa Bay and Charlotte Harbor, Cuban fishermen had also established a rancho on the Oyster River in 1812. According to one report of Tampa Bay: “This is an extensive bay, and capable of admitting ships of any size, contiguous to which are the finest lands in East Florida, which Woodbine pretends belong to him by virtue of a grant from the Indians.”6

Angola’s location also made it easy for communication and diplomacy with the Spanish and British empires. In 1817, there were intelligence reports that Woodbine was amassing a large regiment of Seminole and Black allies in Tampa Bay for the purpose of invading and seizing St. Augustine. This was reportedly intended to prevent the United States from taking acquisition of the territory rather than out of direct animosity against Spanish rule. The rumors never materialized. Arbuthnot and Ambrister, the two British officials executed under Jackson’s orders, had supported the Blacks at Angola with weapons and trade under Woodbine’s orders. Robert Ambrister was commissioned to ensure that the Blacks that Woodbine left at Angola were secure. A witness at his trial reported: “I frequently heard him say he came to attend to Mr. Woodbine’s business at the bay of Tamper.” The same with Arbuthnot: “The prisoner was sent by Woodbine to Tampa, to see about those negroes he had left there.” In 1837, John Lee Williams made observations of ruins left behind from the Angola community as he explored the Oyster River: “The point between these two rivers is called Negro Point. The famous Arbuthnot and Ambrister had at one time a plantation here cultivated by two hundred negroes. The ruins of their cabins, and domestic utensils are still seen on the old fields.”7

Jackson set his sights on the Red Stick and Black refugees almost immediately. In August, several months after his 1818 invasion, Jackson ordered General Gaines to “proceed to, take, and garrison, Fort St. Augustine with American troops, and hold the garrison prisoners until you hear from the President of the United States.” He also ordered Gaines to destroy a settlement of Red Stick followers of Peter McQueen that had returned to the Suwannee River: “I trust before this reaches you, you will destroy the settlement collected at Suwany; this can easily be done by a coup de main, provided secrecy of your movements be observed, and great expedition of march used.” Fearing a potential war with Spain over Jackson’s aggression, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun countermanded his orders in regards to seizing St. Augustine. He wrote to Gaines: “orders in relation to St. Augustine were given . . . You will accordingly, not carry that part of Jackson’s order into execution.” Yet Calhoun did not repudiate Jackson’s command to strike the Red Stick settlement assembled on the Suwannee River. Jackson’s determination to obliterate remaining pockets of Black and native resistance in Florida, as well as Calhoun’s willingness to look the other way out of sympathy with his objectives, would lead to devastating consequences.8

To be sure, the Monroe Administration held many of the same objectives as Jackson: U.S. expansion into Florida and Manifest Destiny, dispossessing the Florida natives and enslaving the Blacks among them, and expanding slavery into Florida. However, they approached matters more cautiously than Jackson. In turn, Jackson, whose temper flared over the “inaction” of the government, made clear his opposition to the “timid, temporizing course of policy” of the Monroe Administration. While holding the same objectives as Jackson, the more sophisticated elites of the ruling class understood that diplomacy and patience were often more efficient than results-driven aggression. But the political discourse on Manifest Destiny, Indian Removal, and slavery expansion remained within tight perimeters, which entailed merely debating the most effective methods on how to achieve these mutually desirable ends. Many also feared that Jackson was becoming too powerful. Addressing Jackson’s fury at being restricted from taking over Florida, Calhoun’s reply reflected both of these concerns:

I concur in the view which you have taken . . . and such, I believe, is the opinion of every member of the administration . . . it appears to me that a certain degree of caution ought, at this time, to mark our policy. A war with Spain . . . such a war would not continue long without involving other parties . . . if it can be prudently and honorably avoided for the present, it ought to be. We want time-time to grow, to perfect our fortifications, to enlarge our navy, to replenish our depots, and to pay our debts. I speak to your frankly, knowing your zeal for our country, whose glory yours is now identified. No whose examined my political discourse will, I am sure, think that these opinions are influenced by timid councils.9

In the meantime, pro-white Creeks were making plans to enslave the Blacks among the Florida natives when the time was right. On October 2, 1818, Creek Indian Agent David B. Mitchell, the former Governor of Georgia, met with several Creek chiefs, including Coweta chief William McIntosh, at his home in Midgeville, Georgia. After discussing plans for the relocation of the Florida natives into the Creek Nation, Mitchell later summarized a part of the meeting: “In the event of their removal [from Florida] I have it in contemplation to Send McIntosh with a Party of warriors to capture and bring away all the Negroes . . . but, if he goes he will expect it to be in the Service of the U States.”10

As if anticipating a last stand, Blacks at Angola began accumulating weapons from their Spanish and British allies. Col. Robert Butler reported that the natives and Blacks were fortifying themselves at Tampa Bay. With reports of Spanish provision of armaments for Blacks and natives at Tampa Bay, General Gaines offered to “do what can be done with the limited means under my control, and strike at any force that may present itself.” In November, it was reported that the natives had also procured “some provisions and ammunition” from “an English trading vessel” at Tampa Bay. According to the report, the Spanish “furnished hostile Indians, at the bay of Tampa, with ten horseloads of ammunition, recommending to them united and vigorous operations against us.”11

Jackson remained adamant in his goal to destroying independent Black, Seminole, and Red Stick settlements throughout the peninsula. In a letter to Calhoun in November 1818, only three months after the previous, Jackson proposed establishing a fort and increasing the military force in Tampa with five or six hundred regulars in order to “insure permanent tranquility in the south.” This detachment was primarily intended to destroy “Woodbine’s negro establishment.” Afterwards, this regiment would move up and station at Picolata on the St. John’s River, proceeding westward to the Suwannee forcing the submission of all “hostile Indians” along the way, who would be then be removed out of Florida and to the Creek Nation. Calhoun failed to authorize the request. Angola had secured itself for the time-being.12

Aside from procuring arms, the Seminoles and Blacks directly petitioned for British and Spanish support. On September 29, 1819, a body of twenty-eight Seminole delegates led by Miccosukee chief Kinache landed on New Providence Island, Bahamas, to solicit the British for assistance. A close ally to head chief Micanopy, Kinache interpreter, described as an “Indian with mixed blood,” may have been the Black Seminole leader Abraham. Having consistently allied with the British on the Florida frontier, the Seminoles had every reason to believe that they would come to their aid. “They represent themselves as driven from their homes and hunted as wild deer,” one correspondent reported, “that there about 2000 of them, and that their greatest enemies are the Cowetas, a nation like themselves, who having made terms with the Americans, are set on by them to harrass and annihilate their tribe.” But fearful of upsetting friendly relations with the U.S. government, the British officials at Nassau declined their request. After being fed and housed for a week, Kinache and his followers were returned to Florida. But evidence of Edward Nicholls’ presence at Angola suggests that the British official, despite Nassau’s official policy, was committed to the promises he had made to help protect the natives and Blacks back in 1815. A year later, four groups of “South Florida Indians” arrived at Havana, comprised of six chiefs and 120 natives from the “coast of Tampa.” Nothing is mentioned about the Spanish agreeing to come to their aid.13

In February 1819, Spain ceded Florida over to the United States in the Adams-Onis Treaty. The pact included a provision that guaranteed protection and rights for the inhabitants of the territory:

The inhabitants of the Territories which His Catholic Majesty cedes to the United-States by this Treaty, shall be incorporated in the Union of the United States, as soon as may be consistent with the principles of the Federal Constitution, and admitted to the enjoyment of all privileges, rights and immunities of the Citizens of the United States.14

While this provision would temporarily allow the free Blacks of St. Augustine and Pensacola to retain their freedom under the slave regime, little regard was given to the Black maroons and Seminoles. In fact, the five million dollars went mostly to Floridian slaveholders who claimed the loss of slaves into Seminole territory, essentially making the fugitive slaves and Black Seminoles property of the Federal government. This treaty provision had various loopholes. Georgian whites did not consider the Seminoles as independent from the Creek Nation and were thus not the “true inhabitants” of Florida. This official doctrine, to be used or discarded selectively, ignored the fact that the Seminoles had established their independence from the Creeks over seventy years before, and that Seminole independence had been a slow process of establishing autonomy on the periphery of the Creek Federation. The policy makers insisted that the Seminoles were outlaws who had “run away” from the Creek Federation. The U.S. government would hold the Creeks accountable for the Seminoles, attempting to enforce dubious reparations through treaty. Whites could also work their way around the Adams-Onis treaty by claiming that the Black Seminoles were recent runaways rather than residents who had established themselves in Florida for over a century.

In January 1821, the Creeks ceded five million acres of their best land through the Treaty of Indian Springs in exchange for $450,000 in annual payments to the Creek Nation over a period of 14 years. However, the Creeks were forced to pay $250,000 out of their annuity to the state of Georgia as reparations for claims of “lost property” of runaway slaves in Seminole territory. On December 29, 1820, the Georgia treaty commissioners delivered a “talk” to the Creek chief council regarding fugitive slaves: “As the negroes now remaining among the Seminoles, now belonging to the white people, we consider those people (the Seminoles) a part of the Creek nation; and we look for the chiefs of the Creek nation to cause the people there, as well as the people of the Upper Towns, to do justice.” William McIntosh spoke to the Georgia commissioners regarding fugitive slaves: “If the President admits that country [Florida] to belong to the Creek nation, he will take his warriors, go down, and bring all he can get, and deliver them up.”15 The treaty fully transformed the Coweta Creeks into determined slave-raiders. They legally claimed the Blacks in Seminole territory as their own property and would feature among the primary antagonists towards their freedom from this point forward. Despite receiving compensation for their fugitives, Floridian and Georgian slaveholders would continue to push claims of ownership of Blacks in Seminole territory as well. Although having already compensated both, the Federal government continued to support their claims by agitating natives to hand over the fugitives and Blacks among them.

When the Adams-Onis treaty took effect on February 1821, President Monroe appointed Andrew Jackson the territory’s first governor, an unsettling development for the Red Sticks and Blacks of Angola to put it mildly. On April 2, 1821, Andrew Jackson requested Secretary of State John Quincy Adams for the President’s instructions regarding the Red Stick Creek settlements scattered along the peninsula, “and likewise in relation to the negroes who have run away from the States, and inhabit the country, and are protected by the Indians.” Adams forwarded the request to the Secretary of War John C. Calhoun. On May 1, Calhoun declined Jackson’s request and ordered him to take no immediate measures.16

In typical Jackson form, he took action before receiving an answer. In late April, chief William McIntosh ordered a war party of Coweta Creeks to go down into Florida to break up the Red Stick Creek settlements and enslave the Blacks at Angola. This raiding party was composed of two hundred Coweta warriors under the command of chiefs William Weatherford and Charles Miller — well-known as close allies of both McIntosh and Jackson. An “eye-witness,” more than likely a participant in the raid, described their objectives in the editorial columns of the Charleston Gazette:

Towards the end of the month of April last, some men of influence and fortune, residing somewhere in the western country, thought of making a speculation in order to obtain Slaves for a trifle. They hired Charles Miller, William Weatherford [and others], and under these chiefs, were engaged about two hundred Cowetas Indians. They were ordered to proceed along the western coast of East Florida, southerly, and there take, in the name of the United States, and make prisoners of all the men of colour, including women and children, they would be able to find, and bring them all, well secured, to a certain place, which has been kept a secret.17

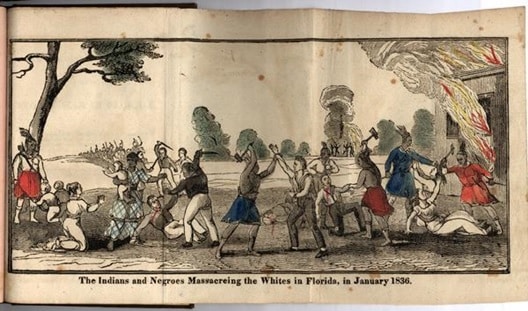

The Creek raiders wreaked havoc throughout central Florida until they launched a surprise attack on Angola and devastated the settlement. The raiders captured over three hundred Angola inhabitants, plundered their plantations, and set fire to all of their homes. Afterwards, the war party made its way south to Charlotte Harbor and plundered several Spanish ranchos. Most of the three hundred Blacks captured in the raid disappeared as the Creek party returned to Georgia. The “eye-witness” in the Charleston Gazette provided a full account:

They arrived at Sazazota, surprised and captured about 300 of them, plundered their plantations, set on fire all their houses, and then proceeding southerly captured several others; and on the 17th day of June, arrived at the Spanish Ranches, in Pointerrass Key, in Carlos Bay, where not finding as many Negroes as they expected, they plundered the Spanish fishermen of more than 2000 dollars worth of property, besides committing the greatest excess. With their plunder and prisoners, they returned to the place appointed for the deposit of both.18

The aftermath of the raid was chaotic for the Black maroons, Seminoles, and Red Stick Creeks in the Florida territory. Settlements were scattered, refugees fled into different areas, and others, having grown tired of the constant terror of U.S. aggression, escaped from the country. About three hundred refugees from Angola left on canoes to the Florida Keys and then left to the Bahamas on British wrecking vessels. The “eye-witness” narrated the aftermath of the assault:

The terror thus spread along the Western Coast of East Florida, broke all the establishments of both Blacks and Indians, who fled in great consternation. The Blacks principally, thought they could not save their lives but by abandoning the country; therefore, they, by small parties and in their Indian canoes, doubled Cape Sable and arrived at Key Taviniere, which is the general place of rendezvous for all the English wreckers [those who profited from recovery of shipwreck property], from Nassau, Providence; an agreement was soon entered into between them, and about 250 of these negroes were by the wreckers carried to Nassau and clandestinely landed.19

A Florida observer wrote that some the blacks from the “Negro Fort,” along with runaway slaves from Florida and other Southern states,

formed considerable settlements on the waters of Tampa Bay. When the Indians went in pursuit of these negroes, such as escaped made their way down to cape Florida and the reef, about which they collected within a year and a half upwards of three hundred; vast numbers of them have been at different times since carried off by the Bahama wreckers to Nassau.20

After the assault, some Blacks armed themselves and remained isolated in the southwest region of the state under the protection of Spanish traders. Some Florida residents petitioned the President to “retain their property” that escaped to an island or cluster of islands off the Florida west coast and were “protected by an armed banditti.”21 In July, a small party of destitute Seminoles made their way to St. Augustine, informing Capt. John R. Bell that “very recently a party of Indians (Cawetus) said to be headed by McIntosh came into their neighborhood and had taken off a considerable number of negroes and some Indians, that the commander of party had sent them information that in a short time he should return and drive all the Indians off.”22 Bell denied that the party was authorized by Jackson or any higher authorities, but failed to acknowledge that McIntosh was Jackson’s proxy who had served under him in his Florida campaign.

A mass exodus of Blacks took place from the Keys to the Bahamas. James Forbes reported that runaway Blacks were amassed at Cape Florida: “At this key, which presents a mass of mangroves, there were lately about sixty Indians, and as many runaway negroes, in search of sustenance, and twenty-seven sail of Bahaman wreckers.”23 Florida officials were not merely satisfied with the Blacks taken during the Coweta raid. In 1823, Governor William Duval wrote to the Secretary of War in apprehension of fugitive Blacks who had escaped Angola to Andros Island, Bahamas:

I have been informed by Gentlemen upon whom I can rely, that there are about ninety negros, fugitives from this Province and the neighboring States, on St. Andrews Island one of the Bahamas, & about thirty more on the Great Bahamas & the neighboring Islands, those Negros went from Tampa Bay, & Charlotte Harbour, in boats to the Florida Keys from whence they were taken to the Bahamas by the Providence Wreckers. The slaves might be obtained, if Com. Porter be ordered to demand them from the authorities at those Islands.24

James Forbes also reported to Secretary of State John Quincy Adams that the Seminoles “apprehend some disturbance from the Cowetas. These last are said to have been at Tampa about 200 strong and taken from thence about 120 Negroes after destroying four Spanish settlements there.”25

But the raid had not solved the problem that the free Black maroons posed in subjugating Florida natives. In July 1821, Jean A. Penieres, Sub-agent for Indian affairs in Florida, gave the first official account of the problem of Black maroon influence over their Seminole “masters”:

We must add to this enumeration. . . . fifty or sixty Negroes, or mulattos, who are maroons, or half slaves to the Indians. These Negroes appeared to me far more intelligent than those who are in absolute slavery; and they have great influence over the minds of the Indians. It will be difficult to form a prudent determination with respect to the maroon Negroes who live among the Indians on the other side of the little mountains of Latchiove. Their number is said to be upward of three hundred. They fear again being made slaves under the American government and will omit nothing to increase or keep alive mistrust among the Indians, whom they in fact govern. If it should become necessary to use force with them, it is to be feared that the Indians will take their part. It will, however, be necessary to remove from Florida this lawless group of free booters, among whom runaway Negroes will always find refuge. It would perhaps be possible to have them received at St. Domingo, or furnish them the means of withdrawing themselves from the United States.26

Responding in September, Jackson concurred with Penieres’ proposal to remove the Black Seminoles from Florida and proposed the establishment of a military base at Picolata to prevent fugitive slaves from escaping into Seminole territory:

This must be done, or the frontier will be much weakened by the Indian settlements, and be a perpetual harbor for our slaves. These runaway slaves, spoken of by Mr. Penieres, must be removed from the Floridas, or scenes of murder and confusion will exist and lead to unhappy consequences that can’t be controlled.27

In August, Creek Agent John Crowell wrote in a letter to Secretary of War John C. Calhoun to inform him of the Coweta raid: “Some short time previous to my coming into this agency, the chiefs, had organized a Regt. of Indian Warriors, and sent them into Florida in pursuit of negroes that had escaped from their owners, in the Creek nation as well as such as had run off from their owners in the States; this detachment has recently returned, bringing with them, to this place fifty nine negroes, besides about twenty delivered to their respective owners on their march up.”28 Failing to mention Jackson’s involvement in organizing the incursion, or that the Creek leaders of the raid were Jackson’s close allies, Calhoun shouldered the blame entirely on the Cowetas. “The expedition to Florida was entirely unknown to this Department,” Calhoun furiously responded in September, “I have to express my concern at, and most decided approbation of, the conduct of the chiefs; that they should seize upon the very moment when that country was about to pass from the possession of Spain to that of the United States, and when everything was in confusion, to use the superior force of the Creek nation over the weakness of the Seminoles, to impose on and plunder them.”29

Objecting to the violent Creek raid of fugitives slaves in the Seminole territory, Calhoun wrote to Florida Indian Agent John Bell: “The government expects that the Slaves who have run away or been plundered from our Citizens or from Indian tribes within our limits will be given up peaceably by the Seminole Indians when demanded.”30 This alternative policy of agitating the Seminoles to turn over fugitive slaves would become the primary point of contention between natives and whites on the Florida frontier for the following fifteen years.

Crowell also understood that Calhoun was more concerned with retrieving fugitive slaves than Seminole impoverishment. He replied to Calhoun in January:

Special orders were given to Col. Miller not to interrupt the person or the property of any Indian or white man & he declares that he did not take from the possession of either red or white person a single negro except one from a vessel belonging to the celebrated Nichols, lying at anchor in Tampa Bay. The negroes he took, were found and acknowledged by the inhabitants of the country to be runaways.31

Crowell then provided a list of 59 slaves that had made it to the United States from the Creek raid, entitled a “Description of the Negroes brought into the Creek nation by a detachment of Indian Warriors under the command of Col. Wm. Miller a half breed Indian.” In turn, Calhoun provided the list to Capt. John R. Bell in hopes that some Florida slaveholders could retrieve their property: “I furnished you with a list of negroes taken from the Seminole Indians by a party of Creeks; by which it would seem that many of them belong to the Inhabitants of Florida.”32

Following the Coweta invasion, slaveholders attempted to retrieve their fugitive slaves who were either seized by the Creek warriors or had fled to the Bahamas. The “eye-witness” in the Charleston Gazette rhetorically concluded his editorial column on the Coweta Creek invasion:

Now all these Negroes, as well as those captured by the Indians, and those gone to Nassau, are runaway Slaves, from the Planters on St. John’s River, in Florida, Georgia, Carolina, and a few from Alabama. Cannot those Planters who have had their Negroes missing recover them by means of these chiefs I have named, and who are so well known by the parts they have been playing for some time past in the late Indian wars, and discover who are those speculative gentlemen who now hold their Negroes, and if they were lawfully their slaves? Could not all those Negroes unlawfully introduced into Nassau be also recovered by an application to the English governor, backed by a formal demand from the Government of the United States?33

But when it came to retrieving the refugee Blacks, Governor Duval’s hands were tied. Duval could not pursue the Black refugees from Angola unless he received permission from Bahaman authorities nor call out a militia against the Blacks in Florida territory unless he received Presidential authority. He instructed Captain Horatio S. Dexter, as he toured Central Florida in 1823, to capture any runaway slaves he found in the vicinity of Tampa Bay and employ an “Indian force” if the slaves resisted. Duval reported that a “considerable number of slaves” had established themselves at Pine Island on the mouth of the Charlotte River after fleeing from Tampa. They were “well armed with Spanish Muskets” and “refuse to permit any American to visit the Island.” Duval estimated that “more than 1,000” runaways continued to reside in the whole territory. The Blacks at Charlotte Harbor maintained their allegiance to the Spanish traders, cutting timber and fishing for the Havana market. In turn, the Spaniards gave them protection with several small gunboats armed with one to three guns each. But Duval could not comply with the demands of slavers unless he received Presidential authority to which he planned to commission sixty mounted militiamen under the command of Col. Gad Humphreys to apprehend the Blacks.34

In his 1823 tour of Florida, Dexter found “eighty refugee Negroes belonging to Indians & Citizens of this territory who are established on the sea coast near Tampa where they are employed by the Havana fishing smacks, & pass to Cuba frequently, the crews of these smacks bring goods to trade with the Indians.” Even some Seminoles, Horatio Dexter found, were often “prevented by force” from communicating with the maroon settlements scattered along the inner islands of southwest Florida, “as the Negroes were all completely armed with Spanish musquets, Bayonets & Cartouche boxes.” Whenever these crews needed cattle, they landed and exchanged powder, lead, molasses, and rum. The marshes between the islands and the main land were shallow, some natives told Dexter, and the armed vessels frequently landed “packages of goods at different depots on these Islands.” These vessels were generally mounted with one, two, or three large guns. After U.S. acquisition of Florida, these Cuban traders carried on a constant communication with the West Indies, Dexter reported, “& have been the means of carrying off a number of refugee Negroes belonging to the inhabitants of this Territory and the neighboring States.”35

The Blacks and Seminoles of Middle and Central Florida also felt the effects of the Creek incursion. From the Suwannee River down to Charlotte Harbor, the Coweta Creek raiders apprehended fugitive slaves and broke up numerous settlements, dispersing the impoverished Floridian natives and Blacks into even more remote locations. About ten miles from the Withlacoochee River, Horatio Dexter found that the settlement of Chucachate, which had formerly been the seat of the Seminole Nation, had been “broken up by the incursions of the Cowetas, who carried off or dispersed about 60 Negro Slaves and a large stock of cattle & horses.” Many Black Angolan refugees fled to the Peace River headwaters. As Dexter traveled farther south toward the Peace River, he came across the remote settlement of chief Opponey. A Red Stick ally of Peter McQueen, Opponey had a plantation situated at Lake Hancock, north of present-day Barstow, Polk County. To the south lied McQueen’s settlement of Talakchopco. His twenty slaves resided on the southeast side of the lake in the town of Minatti (Manatee), which became Angola’s successor. After Opponey’s death, he had left his estate to his son Pulepucka, whose town of Apilchapcocha contained forty natives and seventy Blacks. Many of these blacks at Minatti were Angolan refugees who sought even more remote refuge. There Dexter met some of the kin of the late chief Payne, who informed him: “their object in settling in this remote situation was to avoid the frequent incursions of the Cowetas, whose depredations upon the Indians of the Province ought to engage the early attention of the Agent, and be made the subject of complaint to the Agent of the Creek Nation.”36

In 1822, Dr. William H. Simmons travelled to a Black settlement in the Big Swamp “accompanied by an Indian Negro, as a guide.” En route, he witnessed the effects of the Coweta incursion: “the sites of Indian towns, which had been recently broken up, and the crops left standing on the ground.” These were “chiefly the settlements of Lower Creeks” which had recently “dispersed themselves, or retired to remote situations.” At the Big Swamp settlement, Simmons also found that his Black Seminole hosts had recently fled from their homes in apprehension of the Coweta slave raiders, impoverished and unable to provide him with much hospitality:

These people were in the greatest poverty, and had nothing to offer me; having, not long before, fled from a settlement farther west, and left their crop ungathered, from an apprehension of being seized on by the Cowetas, who had recently carried off a body of Negroes, residing near the Suwaney.37

The Coweta invasion, compounded with Jackson’s invasion, left the Seminoles and Blacks in absolute destitution. Simmons found that “the seizure under the American authority, of a number of fugitive slaves, who had located themselves on the mouth of the Suwaney” had caused many to abandon their settlements and disperse themselves in the woods, leaving their crops to perish on the ground “which, together with the previous loss of their stocks of cattle during the war, had reduced many of them to a state of absolute famine.” Simmons found that the Blacks had grown even more militantly opposed to the United States. As he travelled, with his Black Seminole guide, en route from the Ocklawaha River to the Withlacoochee, he grew notably nervous in the company of several other Blacks who were going the same way: “As many of these Negroes were refugee slaves, and some had been soldiers under Woodbine, and fought against the Americans, I did not feel perfectly safe, while travelling in such company, through swamps and obscure paths, in the Seminole country.”38

U.S. imperialism in Florida led to the increasing decentralization of Black and native settlements. This would, paradoxically, make U.S. efforts to concentrate them within the reservation even more difficult several years later. Native and Black people who had once flourished on the Alachua savannah for almost a century were broken up by the Patriots invaders. Native and Black people who had once cultivated the fertile banks of the Appalachicola River were broken up by a U.S. incursion that slaughtered hundreds at the “Negro Fort.” Native and Black people who cultivated fields along the Suwannee River were broken up by Andrew Jackson’s invasion two years later. Native and Black people who lived off of the fertile lands and abundant hunting grounds in southwest Florida were broken up by a pro-white Coweta Creek incursion dispatched by Jackson. In four separate incursions over the span of a decade, the U.S. made it clear that its Florida policy was to subjugate its free Black residents in order to make it safe for slavery to flourish in the territory. Florida was no longer the safeguard of freedom it once was. Following closely behind the Angolan refugees, Simmons found that many Black maroons and free Blacks in St. Augustine were now fleeing out of Florida to Havana:

The indulgent treatment of their slaves, by which the Spaniards are so honourably distinguished: and the ample and humane code of laws which they have enacted, and also enforce, for the protection of the blacks, both bond and free, occasioned many of the Indian slaves, who were apprehensive of falling into the power of the Americans, and also most of the free people of colour who resided in St. Augustine, to transport themselves to Havana, as soon as they heard of the approach of the American authorities.39

This post is a revised excerpt from A People’s History of Florida 1513-1876: How Africans, Seminoles, Women, and Lower Class Whites Shaped the Sunshine State by Adam Wasserman. Read the free PDF.

Footnotes

- ASPIA, I, 838

- Louis F. Hayes, Letters of Benjamin Hawkins, 1797-1815 (Atlanta: Georgia Department of Archives and History, 1939), 198-200; Canter Brown, Jr., Florida’s Peace River Frontier (Orlando, FL: University of Central Florida Press, 1991), 7-9; Canter Brown, Jr., “Tales of Angola: Free Blacks, Red Stick Creeks, and International Intrigue in Spanish Southwest Florida, 1812-1821,” in Go Sound the Trumpet! Selections of Florida’s African American History, David H. Jackson, Jr., and Canter Brown, Jr., eds. (University of Tampa Press, 2005), 7-8; E.A. Hammond, “The Spanish Fisheries of Charlotte Harbor,” Florida Historical Quarterly 51 (April 1973), 355-80; James W. Covington, “Trade Relations Between Southwestern Florida and Cuba, 1600-1840,” Florida Historical Quarterly 38 (Oct. 1959), 115-129.

- William S. Coker and Thomas D. Watson, Indian Traders of the Southeastern Spanish Borderlands: Panton, Leslie & Company and John Forbes & Company, 1783-1847 (Pensacola: University of West Florida Press, 1986), 301-302, 309, 320; For a complete illustration of the Angola community see, Canter Brown, Jr., “Sarrazota, or runaway Negro plantations”: Tampa Bay’s First Black Community,” Tampa Bay History 12 (Fall-Winter): 5-19; For examples of references to Sarasota as Angola by Cuban settlers and fishermen see, Walter P. Fuller, “Who was the Frenchman of Frenchman’s Creek?” Tequesta 29 (1969), 47-48.

- Young, “A Topographical Memoir,” 97.

- “The Defenses of the Floridas, Report of Capt. James Gadsden,” 49.

- ASPFA, 4, 603; Brown, Peace River Frontier, 8.

- ASPFA, 4, 603, 604; ASPMA, 1, 731; Williams, Territory of Florida, 299-300.

- ASPMA, 1, 744-745.

- Ibid.

- James F. Doster, Creek Indians: The Creek Indians and their Florida Lands, 1740-1823, 2 vols (New York: Garland, 1974), 231.

- Clarence Carter, ed., Territorial Papers of the United States: Territory of Florida, vols. XXII-XXVI (Washington, DC: 1956-1962), Vol. XXII, 167; ASPMA, 1, 752-753.

- ASPMA, 1, 752-753.

- Niles’ Weekly Register, XVII, 243; Rosalyn Howard, “The “Wild Indians of Andros Island: Black Seminole Legacy in the Bahamas,” Journal of Black Studies 37 (Nov., 2006), 280; William C. Sturtevant, “Chakaika and the “Spanish Indians”: Documentary Sources Compared With Seminole Tradition,” Tequesta 13 (1953), 38-39.

- ASPFA, 4, 620.

- ASPIA, 2, 252-253.

- ASPFA, 4, 755; Carter, Territorial Papers, XXII, 57, 40.

- “Advice to Southern Planters” in Charleston Gazette, c. November 1821, reprinted in Philadelphia National Gazette and Literary Register, December 3, 1821, cited in Brown, “Sarrazota, or Runaway Negro Plantations,” 13.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Vignoles, Charles B. Observations upon the Floridas. New York: E. Bliss & E. White, 1823: 135-136.

- Carter, Territorial Papers, XXII, 763.

- Ibid. 126

- Forbes, Sketches, Historical and Topographical, of the Floridas, 105.

- Carter, Territorial Papers, XXII, 745.

- Ibid. 119.

- ASPIA, 2, 411-412.

- Ibid. 414.

- John Crowell to John C. Calhoun, August 20, 1821, in T. J. Peddy, Creek Letters 1820-1824 (typescript in Georgia Department of Archives and History, Atlanta), 21.8.20.C.C.

- J.C. Calhoun to John Crowell, September 29, 1821, Creek Letters 1820-1824, 21.9.29.C.C.

- Carter, Territorial Papers, XXII, 219.

- John Crowell to J.C. Calhoun, January 22, 1822, Creek Letters 1820-1824, 22.1.22.C.C.

- Carter, Territorial Papers, XXII, 221.

- Cited in Brown, “Sarrazota, or Runaway Negro Plantations,” 13.

- Carter, Territorial Papers, XXII, 681, 744.

- Boyd, Mark F. “Horatio Dexter and Events Leading to the Treaty of Moultrie Creek with the Seminole Indians.” Florida Anthropologist 11 (September 1958): 81, 87, 92-93.

- Ibid. 89, 82, 92-93; Brown, “Tales of Angola,” 12.

- Simmons, Notice of East Florida, 41-42.

- Ibid. 84, 44.

- Ibid. 42.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn