For over twenty years, between 1972 and the mid-1990s, activists and community organizers in Washington, D.C. held an annual Malcolm X Day Celebration (MXDC) on May 19. In this personal essay originally published by Black Power Chronicles, activist, go-go group founder, and organizer Charles C. Stephenson Jr. tells the story about how he helped launch that celebration and how it became the longest-running, largest annual event to celebrate the legacy of Malcolm X (El Hajj Malik El Shabazz), the slain human rights leader.

This was also a unique event to honor Malcolm X because it featured go-go bands (learn more about the influence of go-go music at Teach the Beat!) to attract the participation of young people.

Malcolm X Day Celebration

By Charles C. Stephenson Jr.

The first time I attended a Malcolm X Day Celebration was in 1969, in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York. It had a theme of promoting unity in the Black community and included activist speakers like Jitu Weusi along with music from artists who were featured at The EAST, a renowned progressive venue. This event is a prominent recollection because it became the basis for the Malcolm X Day Celebration in Washington, District of Columbia.

At the time, I was 22 years old, living in Mount Vernon, New York, and working in Citibank’s Wall Street office. My community activist efforts mainly occurred through an organization called Black Liberty Thru Black Unity (BLBU), which I had co-founded with my childhood friend Raymond “Omar” Johnson. My work with BLBU and other groups made me want to get more involved in creating social justice for African Americans, and I embraced “Black Power” as the essential element to confront issues that affected our community. I believed Washington, District of Columbia was the best place for m e to exponentially grow these efforts, so a year later, I left New York and changed my career focus from business to community organizing.

As luck would have it, my first job in the District was working with former Congressman Walter Fauntroy to organize Southeast Washington residents and encourage them to participate in the bus boycott of D.C. Transit. Afterwards, I worked with the National Peace Action Coalition to organize a mass demonstration on April 24, 1971, in opposition to the Vietnam War. These sequential introductions to life in the District, anchored my passion to mobilize and organize our community. It was a clear path for me: coalescing our efforts in mass demonstrations was the only way for Blacks in the United States to achieve social justice and improve all our lives.

I believed in the movement and the moment: Black Power was the organizing cry that I operated under to teach people that collective work and responsibility would lead to greater achievements in America. However, I knew that in order to establish a mass movement, we had to mobilize not only the educated, but more importantly, to reach those citizens who suffer daily from American injustices.

During this period, Black activists were also striving to connect issues that affected Africans in America with those that affected Africans in Africa. The African Liberation Day Celebration (ALDC) was thus established in 1972 to gather activists from across the country and acknowledge the ties that bind. The leaders of the ALDC at the time were Jimmy Garrett, Charlie Cobb, Bob Brown, Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), Courtland Cox, Florence Tate, and Cleveland Sellers.

During this period, Black activists were also striving to connect issues that affected Africans in America with those that affected Africans in Africa. The African Liberation Day Celebration (ALDC) was thus established in 1972 to gather activists from across the country and acknowledge the ties that bind. The leaders of the ALDC at the time were Jimmy Garrett, Charlie Cobb, Bob Brown, Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), Courtland Cox, Florence Tate, and Cleveland Sellers.

In 1972, I was attending college along with Morris Johnson — another New York transplant and my best friend. We were both community organizers, focusing most of our attention where we lived in Southeast Washington. Morris and I found ourselves drawn to these efforts to organize the ALDC, particularly to the group of activists and fellow FCC students who were organizing a local ALDC for the District, Maryland, and Virginia residents. These included Rev. Douglas Moore, William “Kojo” Jones, and Ab Jordan of the Black United Front. I also remember working with Edell Lydia, who was later known as Kwame Afoh; he was interested in making sure that locals were involved and would attend the ALDC.

I understood the importance of African Liberation Day Celebration, but I, too, was concerned about how best to translate its importance to my neighbors in Southeast Washington. How could we get them to support issues of African Liberation if we could not show them the intersections with the issues affecting their own lives? We could not.

I suggested a rally in Southeast that would drill down on the issues of employment, education, drug addiction, housing, and so on in a fashion that showed these were the very same issues confronting their brothers and sisters in the African Diaspora. I reached out to Teresa Jones and Gloria Taylor, who were directors of CHASE, Inc., a community-based organization, for contacts and so forth.

The outcome of this outreach was the 1972 Malcolm X Day Celebration (MXDC). It took place on Malcolm’s birthday, May 19.

It was held at the Johenning Baptist Center in Southeast and was used as a pre-rally to ALDC. This was the first of 25 annual Malcolm X Day Celebrations to come; the majority of them were held at Anacostia Park in Southeast.

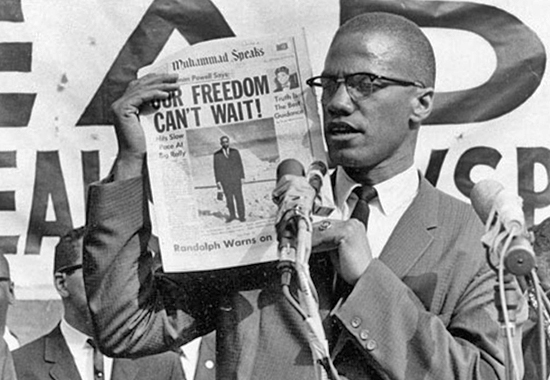

It is important to note why we named this event in honor of Malcolm X. Born as Malcolm Little on May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska, Malcolm X (later known as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz) rose from a background of poverty, crime, and drug use to become one of America’s most dynamic Black leaders of the 1960’s. A former spokesman of the Nation of Islam and the founder of the Organization for Afro-American Unity, Malcolm was respected by both the man-on-the-streets and heads of state for his honest analysis of the plight of Blacks in America.

Malcolm’s triumph over drugs and crime to commit his life to our people’s social, political, and economic uplift exemplified the high standard of social responsibility and cultural identity that we sought to lead by and to instill in all the residents of Southeast Washington, especially young people.

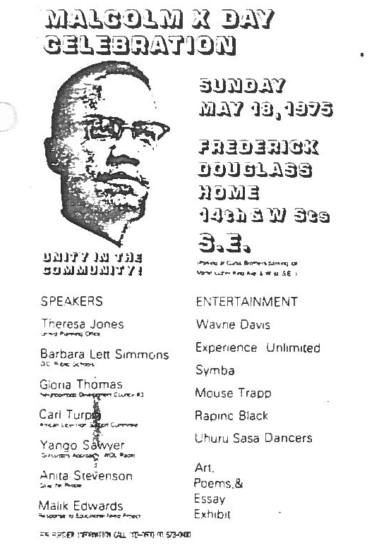

For the next couple of years, I was blessed to be able to attract the artistry, direction, and day-to-day help of Malik Edwards, a former Defense Captain of the Black Panther Party, who was then working in Valley Green, a neighborhood in Southeast. Malik and I worked with Bill Myers of the Black United Front and Vastine Blakeney of the Valley Green Community Center to make the MXDC more attractive, substantive, and effective. Because of the focus on issues of local relevance, the MXDC rally became even more important to us than ALDC.

I must digress for a moment to explain another very important element in the MXDC. It started one evening when Morris and I heard this music from across the hall where I was living. We knocked on the door, and a teenager named Andre Lucas let us in. He was there with Gregory “Sugar Bear” Elliot, Donald Fields, and Ronald Roundtree, the future members of Experience Unlimited Band, now known as E.U. This encounter and my interest in working with young people led me to become their manager. Even though I had no true knowledge of the music industry, how could I refuse a request from teenagers asking for help to be productive young men? Working in the community meant accepting the responsibility to work with the young. The success of the MXDC is directly connected to the fact that E.U. participated in every Celebration for 25 years.

As support for the MXDC grew, the event became more relevant, drew larger attendance, and expanded its activities every year. It became a must-attend event for Chocolate City residents. Our combined focus on local issues and incorporation of positive cultural and musical guests attracted hundreds of people in the first few years. Over the next decade, hundreds grew to thousands.

As support for the MXDC grew, the event became more relevant, drew larger attendance, and expanded its activities every year. It became a must-attend event for Chocolate City residents. Our combined focus on local issues and incorporation of positive cultural and musical guests attracted hundreds of people in the first few years. Over the next decade, hundreds grew to thousands.

In the midst of this growth, internal disagreements within African Liberation Day Celebration led us to focus more on establishing MXDC as a major event of its own. We still encouraged attendees to support the ALDC event, as both now occurred during the same week in May. We even kept our event prior to ALDC so that we would still be in a position to support ALDC, encourage people to attend, and provide momentum for its purpose — connecting the Diaspora.

As Malcolm X Day evolved, its unique focus on local issues of importance to Southeast residents attracted many residents, vendors who wanted exposure, musicians and local artists, community groups that sought to address human service issues and healthcare, and activists and elected officials who wanted to touch base with local constituents. We worked with non-profits, government, and the private sector. As we continued outreach, many reached out to us.

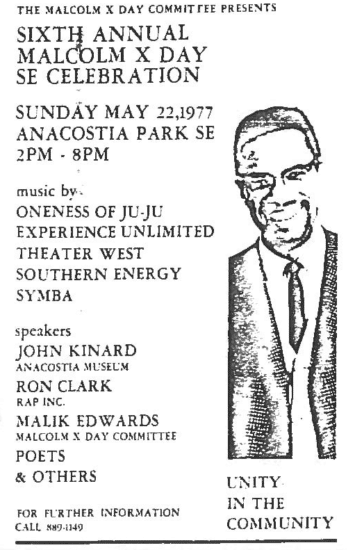

One of our longstanding partners was RAP, Inc., directed by Ron Clark. RAP was a drug rehab program, and our work with their residents and staff enhanced the MXDC. We gave RAP and other organizations a platform to better explain to citizens the services they offered and the challenges we all faced as a community. It is important to note that as far back as the 1970’s, RAP treated drug addiction as a health issue.

In addition to community leaders, we also offered entertainment provided by popular local groups, which included Melvin Deal’s African Heritage Drummers and Dancers and go-go bands such as Chuck Brown and the Soul Searchers, Rare Essence, Trouble Funk, CJ’s Uptown Crew, and of course, Experience Unlimited. This combination of information and entertainment offered to the community became the foundation upon which the MXDC continued to grow.

In addition to community leaders, we also offered entertainment provided by popular local groups, which included Melvin Deal’s African Heritage Drummers and Dancers and go-go bands such as Chuck Brown and the Soul Searchers, Rare Essence, Trouble Funk, CJ’s Uptown Crew, and of course, Experience Unlimited. This combination of information and entertainment offered to the community became the foundation upon which the MXDC continued to grow.

The Malcolm X Day would not have been successful if Malik and I had not learned how to work and coalesce with sectors of the community that historically had not been friends. We learned from Darryll Brooks of Compared to What how to best work with the D.C. Metropolitan Police and the National Park Service. Because the event was attracting thousands of people, we had an added responsibility to make certain that attendees were safe, so we worked with the police, but we also put together our own security headed by Sherry Brown and Rainardo Coward. The National Park Service and the District of Columbia Police allowed our security force to be on the front line to resolve whatever issues arose and to only ask for their support if and when we were no longer effective.

In order to underwrite the costs for holding the MXDC, we had to seek sponsors and partnerships within the community. The United Black Fund (UBF) headed by Dr. Calvin Rolark became our mainstay for financial support. The UBF support allowed us to reach out to other government and corporate sponsors. We were able to attract annual support from the District’s Commission on the Arts and Humanities as well as the city’s Committee to Promote Washington. We even received support from WMATA, which put posters on the Metrobus and Metrorail to promote the event. This visibility enabled us to attract support from major Washington radio stations. Over the years, Bobbie Bennett and Niani Kilkenny with WHUR, Brute Bailey with WOOK, Cathy Hughes with Radio One, Kojo Nnamdi with WAMU, and of course, the full line-up at WPFW would use their airwaves to promote and discuss the annual event.

Because of this growing support, we were able to bring together community activists, civil rights and human rights leaders, and popular entertainment groups to share messages of “Unity in the Community” for 25 years straight. This work could not have been done without the leadership and direction of many local people including Kay Shaw, Sherry Brown, Brenda Jones, John Blake, and Judy Cohall as well as younger activist leaders such as Kemry Hughes, Comelia Sanford, Harry Thomas, Walter McGill, Norm Nixon, and Mark Thompson, who attended MXDC as youth and wanted to be a part of bringing it together.

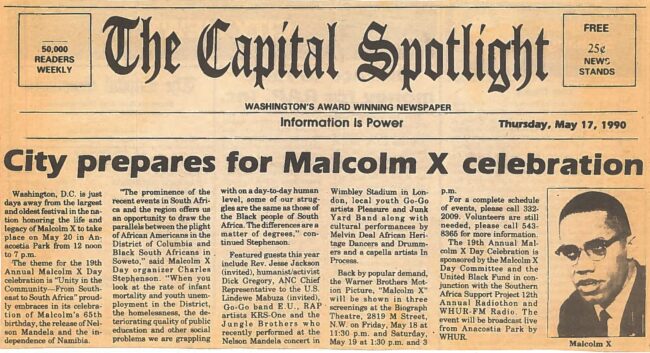

Newspaper clipping from 1990 celebration.

With the help of those mentioned and countless others, the MXDC became the oldest and largest tribute to Malcolm X in the nation. To our sheer delight, the Celebration attracted between 30,000 and 50,000 participants annually, including so many young people, especially Anacostia’s underserved population. Over the years and as word spread about the event and its audiences, the Celebration attracted the voices of those who wanted to speak with such a rich gathering of Black people. Many notables came and honored the organizers and the participants, including the late Dr. Betty Shabazz, Dick Gregory, Marion Barry, Rev. Jesse L. Jackson, Sr., Attallah Shabazz, Sister Souljah, Kwame Ture, and Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton. As a result, the MXDC became a platform to tackle the issues of drug abuse, violence, and unemployment and provide hope, encouragement, and help with daily pressures. Throughout the years, the MXDC received support from all the elected mayors, City Council representatives, and other political leaders of Washington, D.C.

Without a doubt, the success and popularity of the MXDC was consequently responsible for the national resurgence of interest in the life and times of Malcolm X. This interest led to Black youth sporting X caps and T-shirts and quoting Malcolm’s speeches. This activity also ultimately led to Spike Lee’s production of the movie “Malcolm X” in 1992.

It is also important to note the cultural context of the MXDC. Over the years, the event provided a setting to share the rich cultures that make up our heritage. The “Africa Village” section of the event highlighted the works of artists from Southeast to South Africa. Throughout the years, the MXDC has inspired, uplifted, and informed thousands of District residents and hopefully put them on a path for growing responsibility and activism to enhance their lives and their communities well into the future. Although the Malcolm X Day Celebration ended, it continues to live through other events such as We Feed Our People, which since 1988 has provided meals to the homeless on Martin L. King’s Holiday.

I summarize the goal and the result of 25 years of speaking the truth by quoting Dr. Betty Shabazz, who attended and spoke at the Celebration in the 1980s:

Malcolm would have loved this, because he would have the opportunity to speak with the people who needed to hear him.

Published by Black Power Chronicles.

Charles Stephenson is an activist, former legislative director for Congressman Ron Dellums, former chairpersons of the D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities, and founding manager of Experience Unlimited (E.U.), one of the most popular and iconic go-go bands in Washington, D.C. He is the co-author of The Beat: Go-Go Music from Washington, D.C..

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn