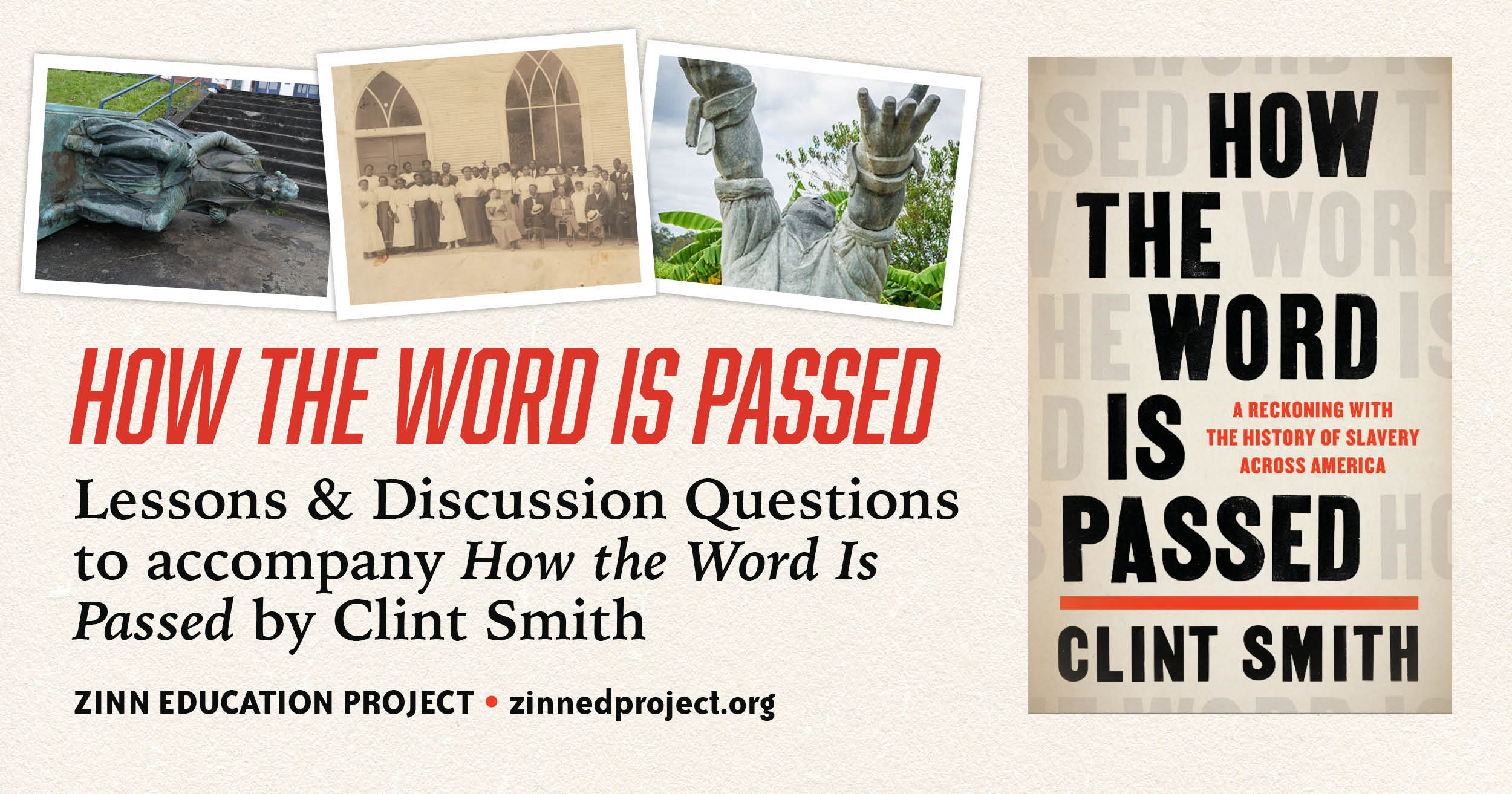

This lesson is part of a suite of activities developed to accompany How the Word Is Passed by a Zinn Education Project curriculum collective, which also includes Jesse Hagopian, Cierra Kaler-Jones, Ana Rosado, and Bill Bigelow.

Salmon Brown, son of abolitionist John Brown, was buried at the Grand Army of Republic Cemetery in Portland, Oregon in 1919. (Click image to learn more.)

Ask any group — children or adults — raised in the United States where slavery occurred in the country, and you will get an overwhelming response: the South.

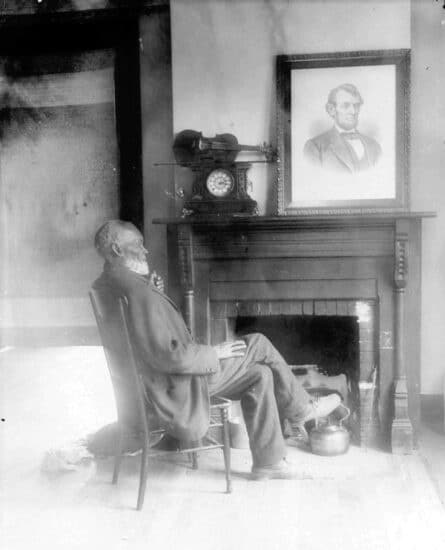

Louis (Lewis) Alexander Southworth (ca. 1830–1917) was born enslaved and moved to Oregon, challenging laws against African Americans in the state. (Click photo to learn more.) Source: State of Oregon

Of course, the question itself is disingenuous. Slavery was a national institution. It “happened” everywhere. Yet the popular discourse of U.S. history suggests otherwise. We read about “slave states” and “free states” or the “antislavery North” and the “pro-slavery South.”

It becomes all too easy to adopt a host of misconceptions: Slavery was limited in scope; it was a regional anachronism; it did not shape the economy and politics of places where it was illegal to own enslaved people.

And critically, it suggests that when we consider the legacies of slavery — as we have in recent national conversations about everything from Confederate monuments to The New York Times 1619 Project, racist policing to reparations — we are talking mostly about only one part of the country.

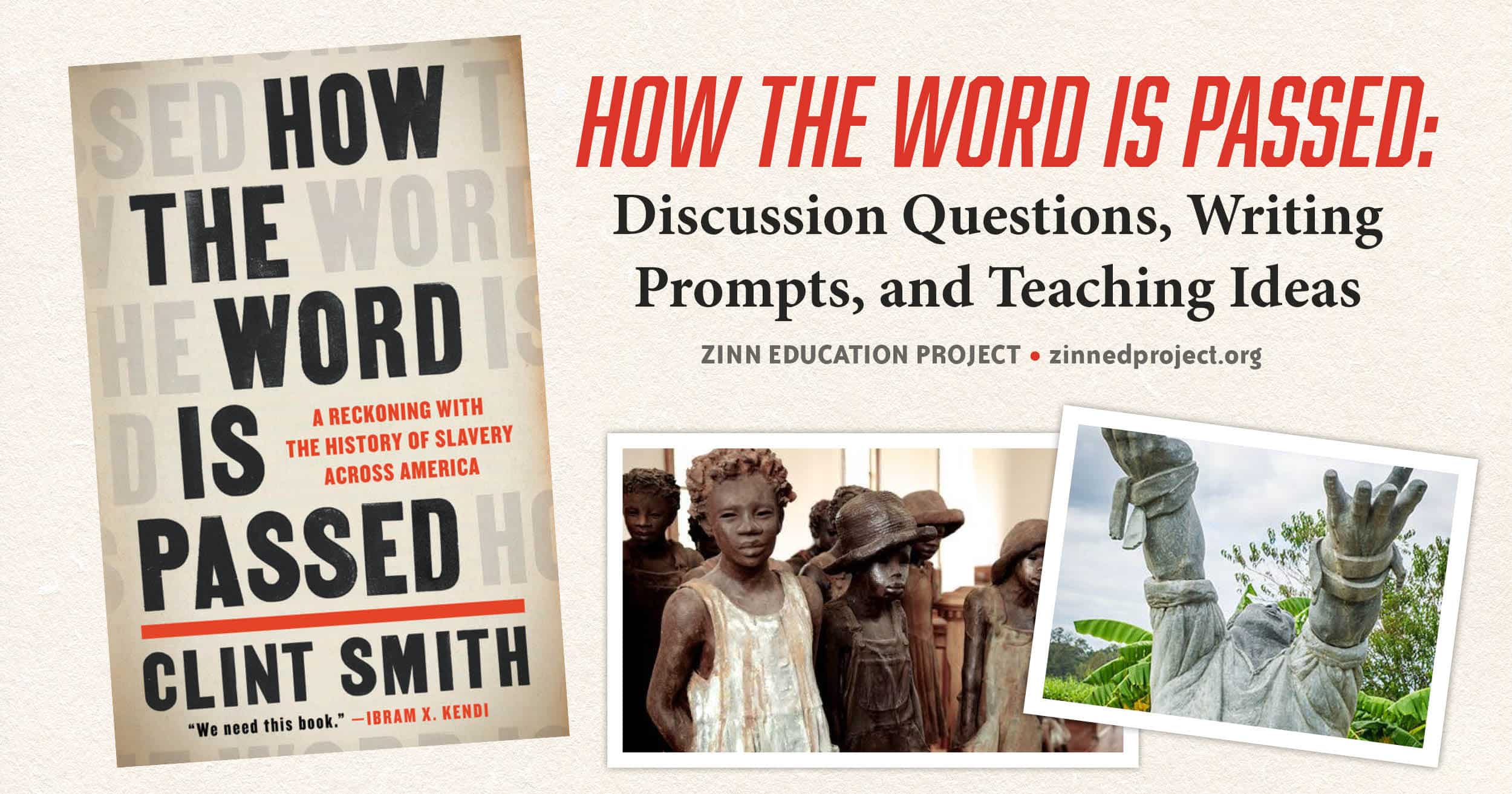

This lesson uses excerpts from Clint Smith’s How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America to invite students to examine their own locales — North and South, East and West, rural and urban — as sites of slavery’s remembering and forgetting.

This lesson uses excerpts from Clint Smith’s How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America to invite students to examine their own locales — North and South, East and West, rural and urban — as sites of slavery’s remembering and forgetting.

It asks students to scan their surroundings for historical traces that live beyond the pages of books, to analyze how these sites help or hinder a clear-eyed view of slavery’s legacy, and to share their critical analysis with each other to “map” slavery’s echoes in their own backyards.

Teacher Story

Sharron Hilbrecht

High School Theology Teacher, Louisville, Kentucky

We talked about the importance of names and stories and remembering.

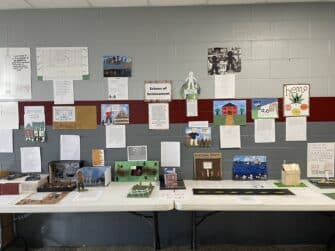

It was a difficult lesson for many of my students. Most of them had never discussed the reality of enslavement in Louisville. Some of them didn’t like having to recognize the fact that many, many places in our city are named after enslavers or were places of enslavement. Some of them got mad. It was not unexpected, and we talked about their feelings and why they felt like they did. I don’t know if I was able to reach them like I would have wanted. I do know that they learned something, even if it made them uncomfortable. [Continue reading]

It was a difficult lesson for many of my students. Most of them had never discussed the reality of enslavement in Louisville. Some of them didn’t like having to recognize the fact that many, many places in our city are named after enslavers or were places of enslavement. Some of them got mad. It was not unexpected, and we talked about their feelings and why they felt like they did. I don’t know if I was able to reach them like I would have wanted. I do know that they learned something, even if it made them uncomfortable. [Continue reading]

Testimonial

I teach Civil Rights to 9th grade ELA students and previously taught U.S. History to 8th grade students. A core part of our 9th grade unit focuses on Clint Smith’s Crash Course Black History series, and Malcolm X and the Rise of Black Power: Crash Course Black American History #38 is one of the anchor sources for our final. Smith’s delivery is one of a collected and enthusiastic historian, and as such, he has become someone my students pay attention to.

During our unit we look at the lesson Echoes of Enslavement in the context of the Civil Rights Movement and the modern era. Even in Washington state, there are prominent areas in which communities fly Confederate flags, and a handful of students at each local high school fly them from their trucks as well. Visible from the freeway is a private monument to Jefferson Davis and two years ago a local high school teacher was reprimanded for passing actual slave shackles around to their students. Students are always stunned to learn that as part of the Oregon Territory, we were the only part of the United States to officially outlaw Black people in their entirety from the region.

Moving into Reconstruction, we analyze redlining in Portland and the destruction of Vanport as legacies of enslavement. Students discuss how these factors have impacted the modern population and politics of the area. By connecting history with personal experiences and connections, students begin to realize and discuss the long term effects of enslavement. Clint Smith is a trusted and reliable source that continues to provide valuable insight for discourse for all ages.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn