Louisville, Kentucky, high school theology teacher Sharron Hilbrecht wrote to tell us about her use of our lesson, “Echoes of Enslavement.” In this lesson students discover “echoes of enslavement” in their own state — discrete sites of remembering, forgetting, honoring, lying, or distorting — based on the book How the Word Is Passed by Clint Smith.

Hilbrecht wrote,

I teach Catholic Social Teaching to high school seniors. As part of our curriculum, we study racism and its causes, and how the history of enslavement still impacts us today. I was looking for an innovative way to talk about this subject when I found the resources on the Zinn Education Project site.

My students read excerpts from “Open Wide Our Hearts,” the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’s (USCCB) letter on combating racism. We then read sections from How the Word Is Passed to bring home the point that we are still impacted by the echoes of enslavement. We brainstormed places in Louisville, Kentucky, that are named after enslavers or were places of enslavement. After we had a good list on the board, the students spent a class period browsing the internet to see which one interested them the most.

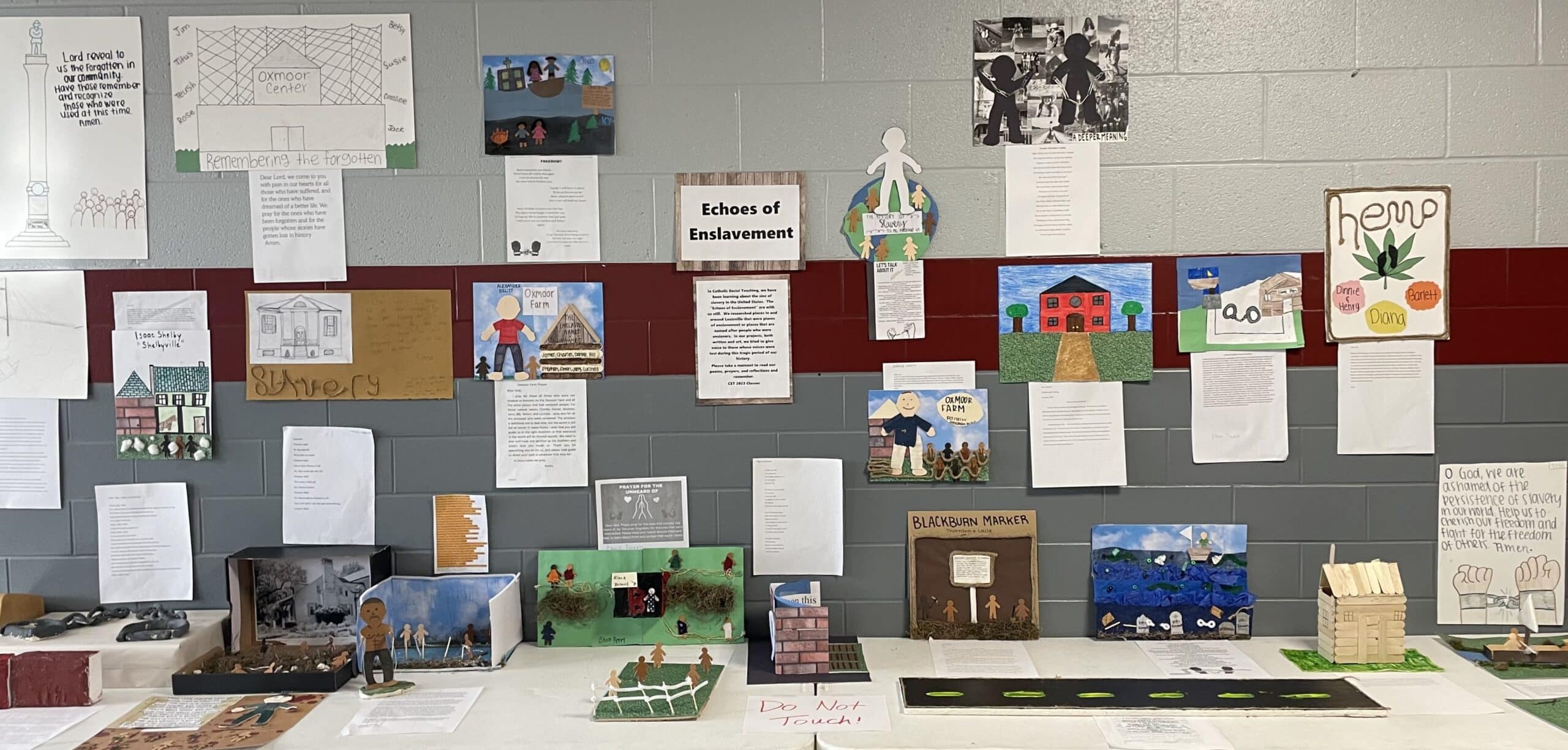

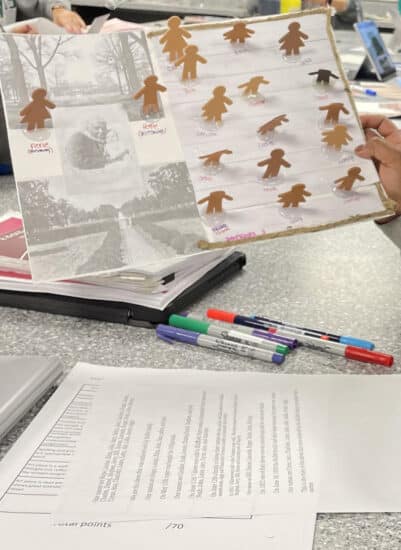

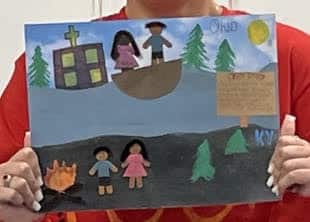

When they had decided on their place, they used some of the suggested questions from the Zinn Education Project lesson plan to get information down, and I encouraged them to follow any leads related to the place that they found interesting or helpful. Once they finished their research, they created a written piece to give voice to those whose voices were lost to enslavement and time. We also went to our Maker Space, where they created a visual art piece to accompany the written part. They then presented their findings to the class, and we displayed them in the hall.

These were part of the guidelines for this project:

Once you have chosen a spot, create a written piece that answers several of the questions above (questions from their research) and gives a “voice” to those forgotten over time. The piece should describe the location and help the reader see there are still echoes of slavery in Louisville. It should be thoughtful and invite the reader to consider those whose names and stories have been lost to time. There is no page requirement except that whatever is written fulfills the guidelines above and in the rubric. The piece should NOT be hateful, bigoted, or mean-spirited. No name-calling.

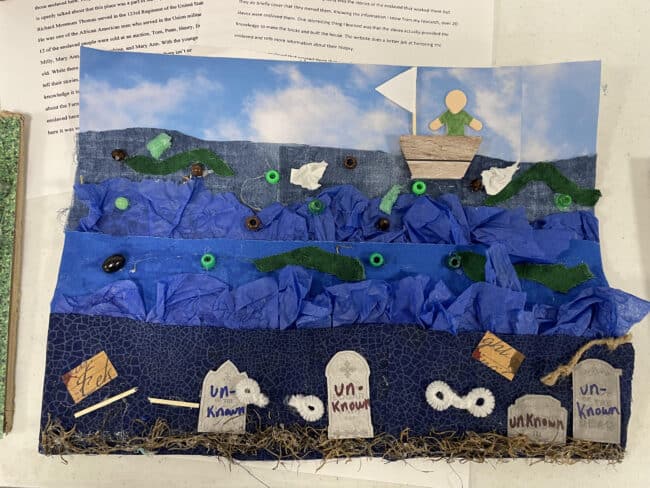

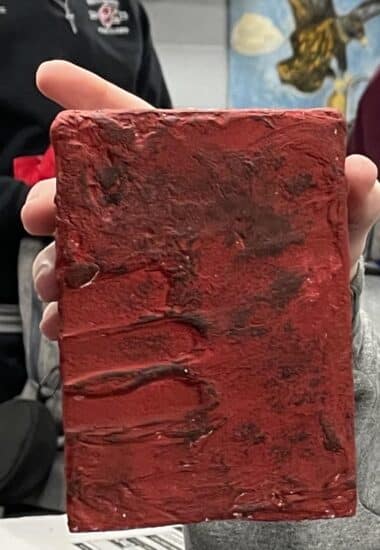

After the piece has been written, you will create an art piece that represents the space you wrote about. Like the written piece, the artwork should reflect the space chosen as well as the written piece. It should also help people to see the echoes of slavery in Louisville.

While this assignment may stir up a lot of feelings, the assignment’s goal is to bring a voice to those whose names we do not know and whose stories have been lost. The assignment is meant to be a bridge to the past to help bring awareness of the impact that enslavement had on people in our history. The hope is that it will help create dialogue and healing.

I have never seen the students so engaged. They had no idea how many places in our city are Echoes of Enslavement. Once they started researching, they found themselves going down rabbit holes to learn more. For example, one student researched the Oxmoor Mall, which was once the Oxmoor Plantation. She found out that it was owned by the Bullitt family, who enslaved dozens of people on the property and have a county named after them. I encouraged the student to look deeper to see if she could find any documents that named the enslaved, and she found a will that named several people. The student wrote a poem about the place where people now shop and play Topgolf, that has no mention of what used to happen there. The art piece was a picture of Topgolf surrounded by the names she found in the will. She was also inspired to contact the mall managers to ask them to recognize those who once lived and worked on the property.

I have never seen the students so engaged. They had no idea how many places in our city are Echoes of Enslavement. Once they started researching, they found themselves going down rabbit holes to learn more. For example, one student researched the Oxmoor Mall, which was once the Oxmoor Plantation. She found out that it was owned by the Bullitt family, who enslaved dozens of people on the property and have a county named after them. I encouraged the student to look deeper to see if she could find any documents that named the enslaved, and she found a will that named several people. The student wrote a poem about the place where people now shop and play Topgolf, that has no mention of what used to happen there. The art piece was a picture of Topgolf surrounded by the names she found in the will. She was also inspired to contact the mall managers to ask them to recognize those who once lived and worked on the property.

Another student researched the slave pen in downtown Louisville, which is now a parking lot next to a restaurant and across from our big arena. There is a small marker but nothing more; easily missed in the drive downtown. Two girls collaborated on an historic home near our school. It was owned by a family who now has roads and a middle school named after them. They also enslaved several dozen people. The girls wrote a poem and then created bricks with fingerprints embedded in them to represent the labor that went into making this beautiful home.

Another girl printed pictures she had had taken of herself at this same location before she knew it was a place of enslavement. She covered a small poster board with the pictures of friends, prom, etc., printed in black and white. Over the top of those pictures, she pasted silhouettes of people to represent the enslaved. She titled it, “A Deeper Meaning.”

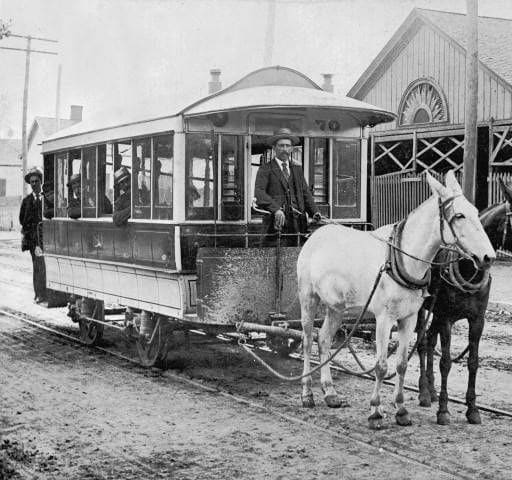

Many of them researched the Ohio River because they said they had never thought of that as a place of enslavement. We talked as a class about how it was both a barrier to freedom and a beacon to freedom as well as a path to deeper enslavement when people were sold at the slave pens and shipped farther south. During the research, two students discovered Thornton and Lucie Blackburn’s marker along the river and decided to dive deeper into their story. They discovered that the Blackburns were freedom seekers who crossed the river and ended up in Detroit and eventually in Toronto, where Thornton started the taxicab service.

One thing we really focused on was language. They had not been exposed to the terms “enslavement,” “enslaver,” and “enslaved people.” We discussed how it was important to recognize that enslavement was a condition and didn’t define who the people were. We talked about using “freedom seekers” instead of “runaway slaves” and how using these terms gives some agency back to those people’s lives. I watched my students’ language change as they caught and corrected themselves.

We talked about the importance of names and stories and remembering.

It was a difficult lesson for many of my students. Most of them had never discussed the reality of enslavement in Louisville. Some of them didn’t like having to recognize the fact that many, many places in our city are named after enslavers or were places of enslavement. Some of them got mad. It was not unexpected, and we talked about their feelings and why they felt like they did. I don’t know if I was able to reach them like I would have wanted. I do know that they learned something, even if it made them uncomfortable.

Some students did “get it,” and I was happy about that. Here are a couple of their comments:

I enjoyed getting to learn more about enslavement in my community because it’s not something that you ever really think about, and to be able to do research and see how it has impacted places was very interesting.

I like that it gave us new information and told us something we didn’t know about our community. Also, bringing more awareness towards the meaning and history of the things in our community.

Hilbrecht added,

Thank you for the idea for this lesson. I believe it was impactful, educational, and long overdue. I will teach this again next year.

Please share your story of using How the Word Is Passed lessons. We can send you copies of the book in appreciation.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn