by William Loren Katz

Though the Civil War and Emancipation are celebrated this year, people of color who emancipated themselves are rarely mentioned. One such group in Robeson County, North Carolina, was the Lowry Band. Their ancestors included English survivors of the Lost Colony of Roanoke mixed with Lumbee Indians mixed with self-liberated African men and women from the southern British colonies. To the Confederate Home Guards of North Carolina, they were “mixed bloods,” “swamp fighters,” and much worse. The Lowry Band and the Home Guards fought their own civil war.

By 1864, Henry Berry Lowry was the Lowry Band’s leader and military commander. The Lowry Band clashed repeatedly when Home Guards tried to seize and force their men to build Confederate fortifications. The Lowry Band had no use for the Confederacy, forced labor, and the fact that some of their kinfolk were enslaved by Confederates. The Home Guard claimed Lowry’s men—who welcomed, recruited, and armed fleeing Union prisoners, African American runaways, and Confederate deserters—wanted to overthrow slavery. They charged that the Lowry Band hid guns, stole meat, and robbed from the rich.

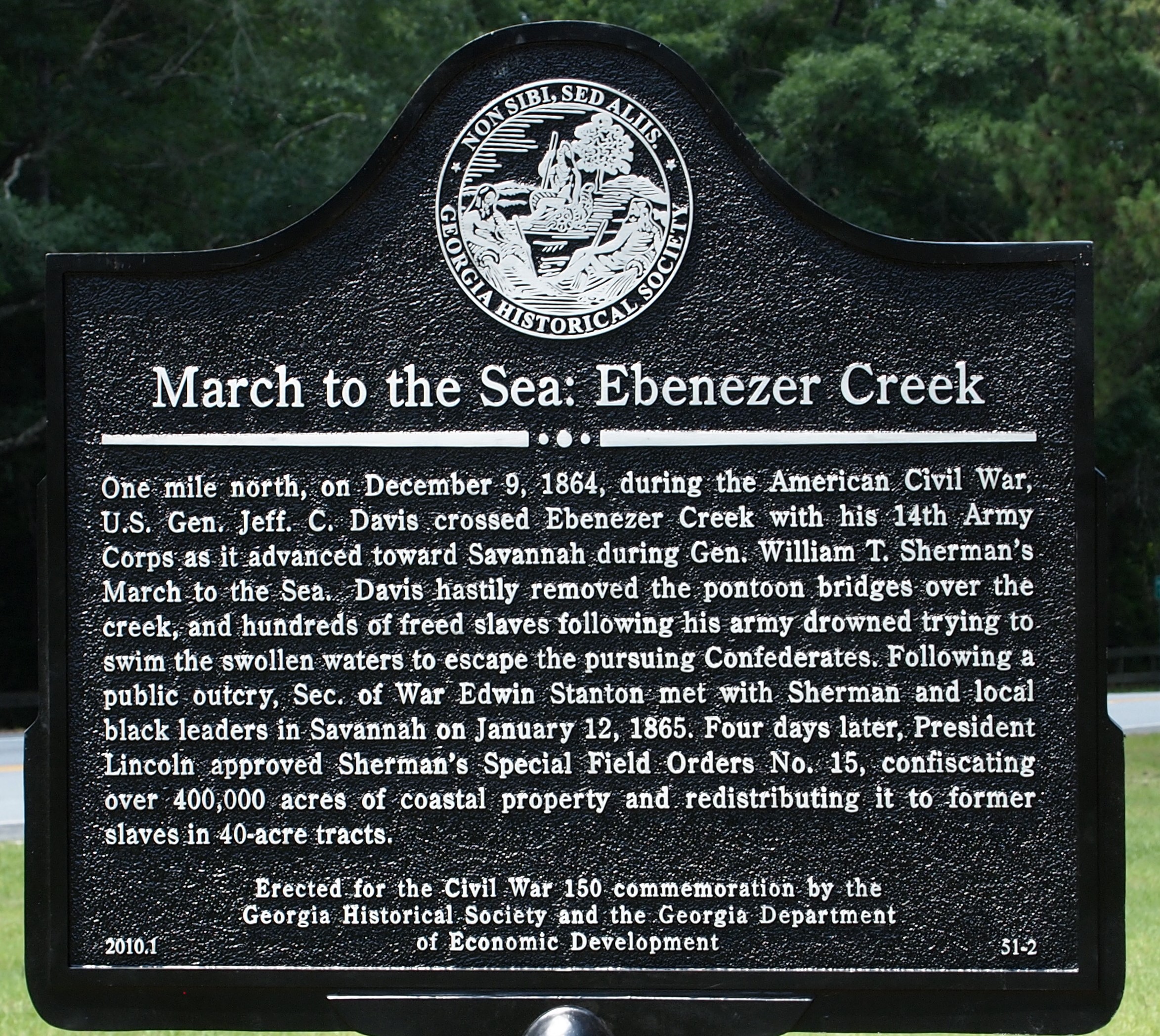

Lowry’s men and women clearly had no intention of helping slaveholders, or assisting the Confederacy when U.S. General T. Sherman and his Union Army reached North Carolina in late 1864. Gen. Sherman had decided he could end the war if he sliced the Confederacy in half by cutting through Georgia to its capitol at Atlanta, and then on to Savannah on the Atlantic Ocean. With 60,000 men and no contact with supply lines—but aided by slave runaways—his soldiers lived off the land, and cut a path of grim desolation. From Savannah, Sherman marched his army northward into South Carolina, the fountainhead of the pro-slavery secession movement.

Sherman next wheeled his forces toward North Carolina to cut another devastating slice through the Confederacy. His army reached Robeson County, on March 9, 1865, only to be stopped by a torrential rain, muddy roads, and swollen creeks. They could not move, or even knew where to move.

Suddenly out of the downpour appeared a dark, shabbily dressed, grizzled guerrilla force that offered to help. Sherman called his saviors “Lumbees,” but they were men of the Lowry Band. They led Sherman’s army through the torrential rain and treacherous swamps. Sherman thanked his saviors for “the damnedest marching I ever saw.” Then in concert with Union Gen. Grant from the North, Sherman went on to bring the Civil War to an end. On February 22, African American Bluecoats liberated Wilmington, N.C. On April 9, Confederate Gen. Lee surrendered to Grant, and two weeks later, on April 26, Confederate Gen. Joseph Johnston surrendered to Sherman in North Carolina.

Call them Lumbees, the Lowry Band, or Black Indians, these swamp fighters of Robeson County did their part to defeat the Confederacy and end slavery in the United States.

The people of color in Robeson County never forgot their courage. In 1976, residents of Robeson County produced “Strike at the Wind!”—a two-and-a-half-hour outdoor play about the Lowry Band and its seven-year war. Descendants of the Lowry Gang were among its writers and the 1,000 actors who played their part over the next 30 years.

This essay is adapted from the 2012 expanded edition of Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage by author William Loren Katz. His website—www.williamlkatz.com—has other articles on the subject and his 40 books.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn