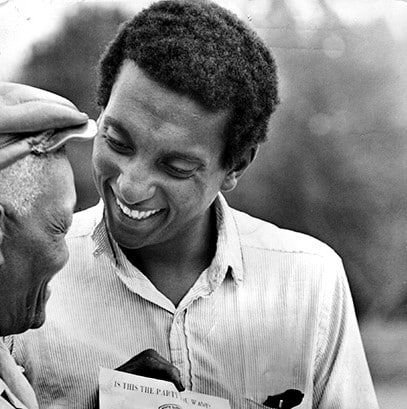

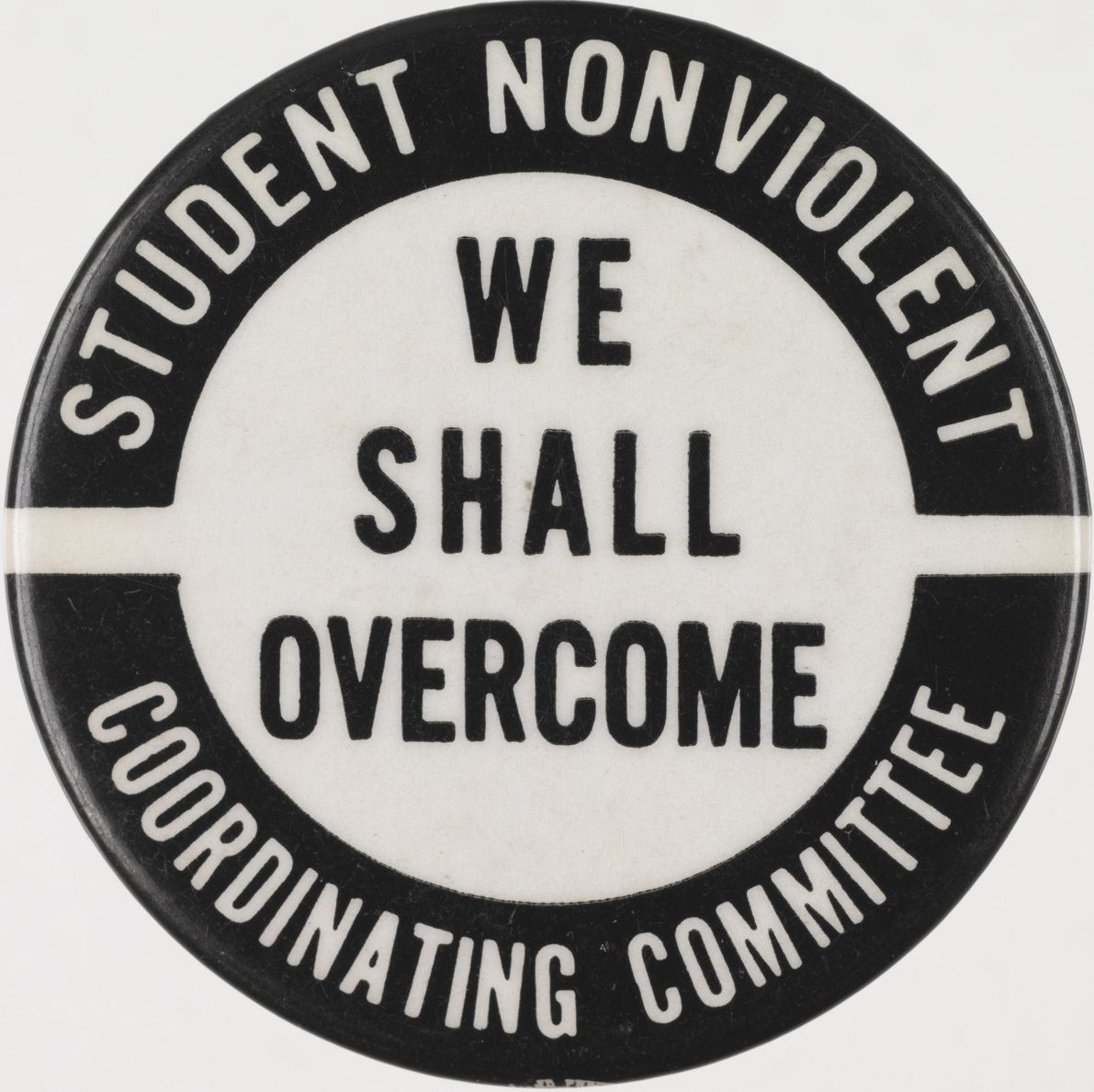

As part of the SNCC Legacy Project’s SNCC & Grassroots Organizing series, on April 26, 2024 at Howard University, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee veterans Courtland Cox and Jennifer Lawson, and humanities scholars Catherine Adams and Hasan Kwame Jeffries, sat down for a Black Power roundtable discussion.

Here are a few video recordings from the discussion along with corresponding transcripts.

SNCC Veteran Courtland Cox on Howard Student Activism and Its Legacy

Transcript

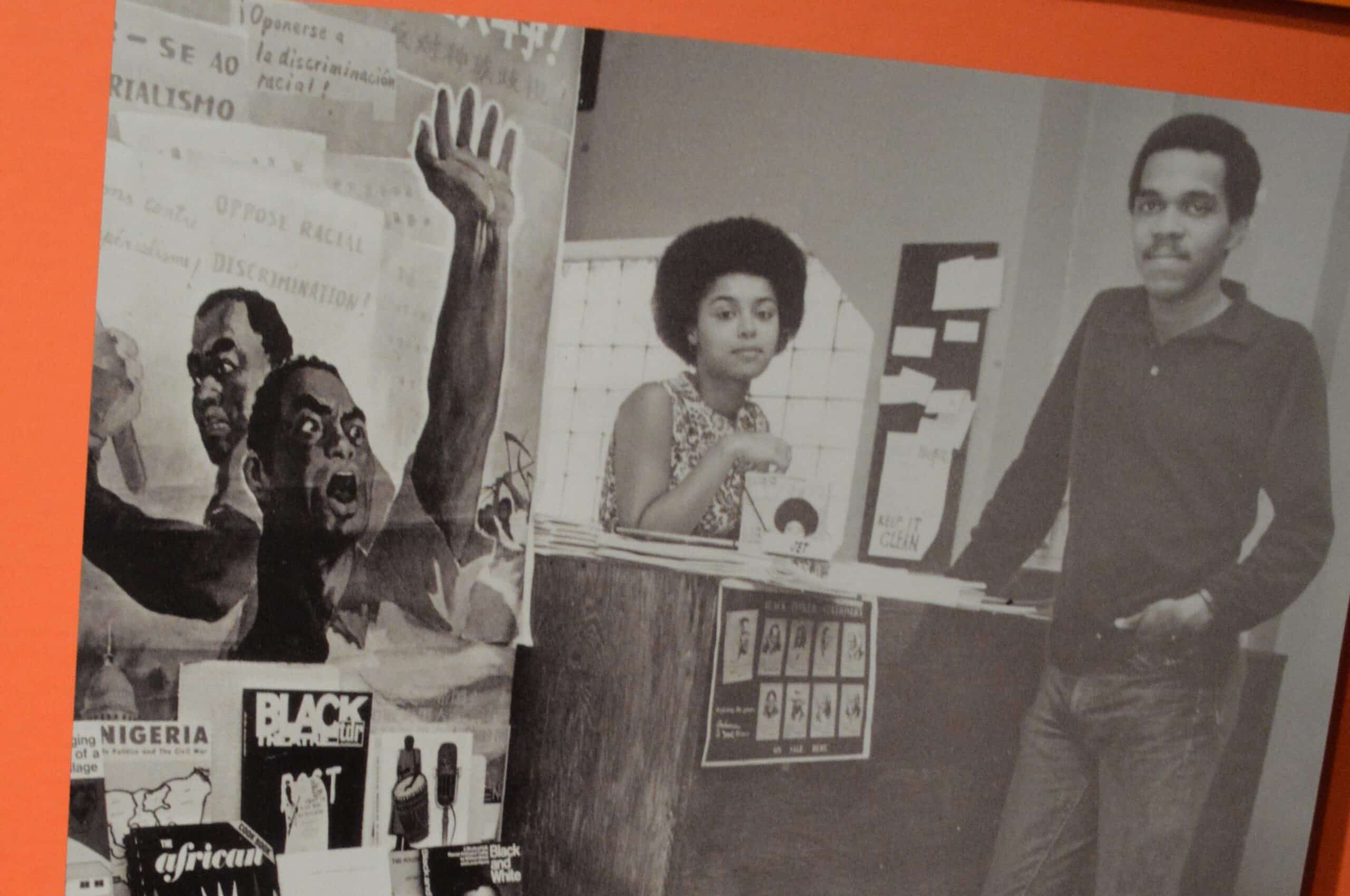

Courtland Cox: Stokely Carmichael, Kwame Ture, attended Howard; we were here at the same time. We were very, very, very fortunate because everything we did really was started and supported by the generations before us, and I want to pay particular acknowledgement to people like Sterling Brown, who would come to the dormitory and would, one day or one week, do a piece on blues or on jazz, or he would do it on poetry. Or he would invite us to his house and we would drink liquor and he would tell us about [W. E. B.] Du Bois. He put us in the history.

Then we had at that time E. Franklin Frazier, who wrote Black Bourgeoisie. Even though I didn’t take his class, I could go audit his class at Douglas Hall. Michael Thelwell, who was mentioned earlier, was the editor of The Hilltop. Stokely Carmichael and another person at NAG was in the Student Council of Howard University. We created a thing called Project Awareness that brought Malcolm X and Bayard Rustin in 1961 to debate the question of separation versus integration. We had a symposium with James Baldwin, John Killens, and Ossie Davis talking about the Negro writer. We had an after party and Sidney Poitier flew in to say, “I heard the boys were in town, so I figured I’d show up.” We were all teenagers but we empowered ourselves in terms of the things that we did, whether it was being the editor of The Hilltop. Charlie Cobb was the editor on The Hilltop. We had people on the Student Council. We created the programs.

SNCC Veteran Jennifer Lawson on Laying the Groundwork for Student Activism and Black Power

Transcript

Jennifer Lawson: For example, at Tuskegee I learned more about voting from a man there who was a Professor [Charles] Gomillion, who had taken a case. I mean, I had never heard of this whole expression of gerrymandering, and this man then was telling us students about how you could be cheated of the right to vote by them re-zoning the area that you lived in, and that there were all of these people, brilliant attorneys, entrepreneurs, who all contributed to create an atmosphere for our generations. For us younger college students at that time, they had laid the groundwork, a series of steps. But we took it upon ourselves to give it our own definition. And we’ll come back to talk about how then the students at Tuskegee joined with the students from Howard and other places in working towards Black power.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries on SNCC and “Bloody Lowndes” County, Alabama

Transcript

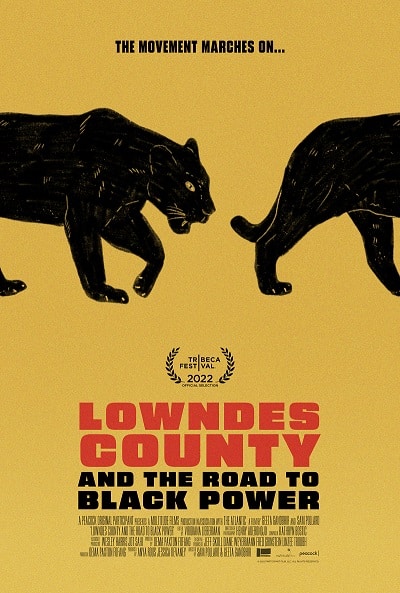

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: Certainly. Lowndes County, Alabama is a majority Black county in the heart of Alabama’s Black Belt, situated between Montgomery and Selma. Starting in 1965, Lowndes County, Alabama is 80% African American and has zero registered voters — 80% African American. Not a couple, not a handful. Zero. Political exclusion in Lowndes County, Alabama was absolute, it was long standing, and it was done through the usual mechanisms of poll taxes, literacy tests, and all this other stuff. But it was really enforced through racial terror. Lowndes County, Alabama had a well deserved nickname of “Bloody Lowndes” because of its long history of racial terror. So, the way political disenfranchisement was maintained was through the use of violence and through the use of terror and the long memory of it. This wasn’t anything recent, this sort of intergenerational trauma of people understanding that if you can test power you don’t just run the risk of losing your job or losing your home, you run the risk of losing your life.

This is the context into which the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee enters, choosing intentionally to go into a place called Bloody Lowndes, understanding that if they can organize Lowndes County then it will become easier to organize the other counties. Intentionally choosing to go into the place that was most dangerous, a place where SCLC and Dr. King were like, “Yeah, can’t nothing be done there.” So they said, “Let’s go there.”

Hasan Kwame Jeffries on Lowndes County, the LCFO, and Ella Baker

Transcript

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: At the start of 1965, there were zero registered voters, [it was] 80% African American, [with] 5,122 African Americans who were of voter registration age. At the end of 1966, not only had this partnership between SNCC activists and local people succeeded in registering the majority of African Americans, they had helped create a grassroots, independent political party, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, Lowndes County Freedom Party, the original Black Panther Party, which on its own would be amazing.

What’s so critically important and valuable about what they did is that they not just created this parallel, truly independent political party at the county level, determined to seize control of the mechanisms of local power, but they infused in it this democratic culture of political organizing. We hear a lot about Ella Baker and Ella Baker’s organizing philosophy. Well, Lowndes County was the political actualization of Ella Baker’s organizing philosophy. This is what it would look like beyond just helping people get the ballot in hand. But, as Courtland would write, would say, and would argue, now that you’ve got the vote, what are you going to do with it? Well, in August of 1965 was when the Voting Rights Act would be signed into law. The question then becomes, What do you do with it? Lowndes County offered the answer. It’s about independent politics. It’s about seizing control of the mechanisms of power and empowering everyday people, local people.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries on Lowndes County as a Model for Black Power

Transcript

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: One of the amazing things that happens in Lowndes County is the development of the political culture there that says, wealth, whiteness, and previous political experience are not prerequisites for holding office. We’re done with that. If you are a citizen, if you are here, all you need to do is learn what the duties of elected officials are, then you yourself are capable of holding office and empowering local people. It’s one thing to say, “Hey, the Black Panther comes from Lowndes County, Alabama. This political tradition of independent politics comes from Lowndes County, Alabama.” But this political culture, this small d democratic political culture that emphasizes not just political mobilization but political education is one of the critical lessons that comes out of not just SNCC and Lowndes County, but the movement as a whole. Which, unfortunately, we’ve gotten away from. We can get anybody to the polls. We know how to do that today. But do we know how to engage in that kind of political education so that they’re still active, not just on election day, but on the days afterward? And Lowndes gives us that model for how to do that.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries on SNCC and the Lowndes County Freedom Party

Transcript

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: At the same time that SNCC was organizing the Lowndes County Freedom Party and working in some other counties in Alabama to organize independent parties, you also had the SCLC, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, King’s organization in 1966, that was also operating in Alabama, urging newly registered African Americans to vote — not for their own independent candidates, but for a slate of moderate white candidates. Moderate whites in Alabama were like the klan without a robe. But there was a difference. When they have the primary, all those moderate white candidates never actually win anything, so those left to actually vote for in a general election would be these independent candidates. But the listening part is key to everything that goes on in Lowndes County, because the difference between SCLC and SNCC in this moment, in this example, is that the SCLC is going into these communities and telling Black people what to do. “You’re going to vote for these candidates. Don’t waste your time voting for these independent candidates. Vote for these moderate whites.” They’re telling them what to do; they’re not asking them what they want. And the reason why they were doing that — and this really becomes the big difference between the SCLC and SNCC — is that SNCC took ordinary folks, everyday folks in these communities, in these counties, they took them seriously as political thinkers.

That’s why they’re doing these cartoon story books. They’re giving them information that was withheld from them. They believe that, given this information, they could use it in ways that would be productive, to make the decisions that affected their lives. They were taking them seriously as political thinkers. SCLC was not taking Black folks — ordinary Black folks, sharecroppers, domestic workers with fourth and fifth grade educations — seriously as political thinkers. And that was a critical mistake because Black folks have been thinking critically about politics from the moment they were re-enfranchised as Black men in 1870, until the moment in Alabama in 1901, when the vote was stripped from them by a disenfranchisement constitution.

That was one of the beautiful things about the organizing work that SNCC did, taking Black people seriously as political thinkers. This is how we can mobilize and organize in these communities, then translating that to electoral politics. We’re not going to go in and tell you what you’re going to do. We’re going to provide you with the information that has been withheld from you, because we believe and we know that given the right information you will make the right decision.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries on the Legacy of Black Power

Transcript

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: Part of the reason why we are obsessed with the Civil Rights Movement is because we have framed the Civil Rights Movement as a success or failure depending upon proximity to whiteness. We talk about the Civil Rights Movement in ways that are designed to make white people comfortable about that struggle and not about the ways in which it actually was. So thinking about creating struggle nonviolently, divorced from the ways in which nonviolent struggles are actually a radical way to fight, but framed as a way of pleasantries robs it of its power in that particular movement. But that’s what we’re left with. When we look at the introduction of nonviolence as an organizing strategy, as an organizing tactic, that really surfaces and enters the African American community in a particular moment, in the late 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, that’s what was really different in the African American Freedom Struggle. Too often we look at Black power and we say, “Black power is the break from what came before.” It’s not.

What was a break was the idea of introducing nonviolence as a way of life that a small group of people really cling to. I mean, they’re committed to it and it’s powerful, but that ain’t the majority. So, when SNCC in Lowndes County, Alabama, and elsewhere are talking about creating independent political institutions, this is Black power. The Black folks in Mississippi and Alabama — forget about Detroit, Cleveland, New York, and LA — Black folks in these rural counties are like, “Yeah, that makes sense because this is what the hell we’ve been doing since slavery. This is how we’ve survived.” This question of solidarity at the moment of Emancipation, when Black folks have the opportunity to be free, how do they define their freedom? By creating independent Black institutions, Black churches, Black businesses, Black schools, Black cooperatives. This is how Black folks survive, with a conscious emphasis on Black solidarity.

That’s what Garveyism was. So, the rupture suddenly becomes the conversation around nonviolence, which shifts some of the analysis as being the problem that Black people facing is primarily moral. And some folks believe that. But, one of the things that we saw coming out of Howard University was the moral thing. Yeah, there’s a moral problem in America, but the issue we’re dealing with is an issue of power. And if a problem is fundamentally about power, then the solution has to be about gaining power. So when that is proposed, when that is articulated, starting in 1966 and 1967, then you have Black folks responding, like, “Yeah, it makes sense.” And that’s what ripples out. So Black power introduces something new, it interjects a new energy, and it will transform the Black Freedom Struggle going forward. But it’s not a rupture and a move in a different direction; it’s actually a return to what Black folks have been doing in an updated way.

So, drawing on the historical traditions of Black solidarity and Black institution building, now we begin to see Black power making this tremendous contribution, not only in terms of African Americans being elected to office — whether they’re independent political parties or Black folks coming together to elect Black mayors in various cities. D. C. being one of them, Cleveland and New York eventually down the road, and Chicago. But what do we see? Black folks coming together, Black professionals forming Black professional organizations. We have the cultural component, the challenging of white supremacy. That was real. We were creating our own Black institutions coming out of Emancipation, coming out slavery, because we knew this was important, creating these Black churches, leaving these white churches. But taking that one white member with us, that white Jesus. So, we were still caught up with that white supremacy so that had to be dealt with, and Black power said we’re going to deal with that. But one of the primary legacies, too — and I think this speaks to the current moment — one of the primary legacies, too, is the creation of Black Studies and the creation of Black Studies Departments because that deals with the intellectual. And that’s the transformation, because that’s the educational key. That’s how the organizing will get transferred. That’s how it’s beginning to open up the critique of, “No, you’re not going to be anti-African anymore. We’re changing that.”

And that legacy then trickles down, not only from student organizing on Black college campuses, but then trickling down into public schools, trickling down to K through 12. So, fast forward thirty or forty years when you get to the Black Lives Matter movement and the Black Lives Matter moment. People were like, “Oh, this is the Civil Rights Movement.” No. Black Lives Matter had more of a connection with Black power than with civil rights. Then think about fast forwarding another couple of years to 2020, 2021, 2022, when we get this pushback, this anti Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, DEI, the anti-CRT. Why?

It goes back, I think, to what Courtland was pointing out. The legacy of Black power was not only getting Black students to think critically about the world in which they were living and the limits of it. But, we see forty or fifty years after calling for Black power, that white students start to question the same. So in the summer of 2020, when you get millions of white kids heading into the streets talking about, “We need to end systemic racism,” that’s nothing but a Black power critique. But there’s only one response that you can have to that: change institutions. You’ve got to change systems and structures, and that is a role that those who benefit from the existing systems and structures were not going to cross.

So, part of the pushback is a reflection of the success of the Black power critique that is borne of the influence that it had on higher education trickling down into K through 12. We’re dealing with the legacy of it, but also the pushback to that legacy, not because we were unsuccessful, not because Black power activists, not because SNCC activists, were unsuccessful in changing the way people think, but because they were successful in doing it. And now it has scared the shit out of political conservatives who benefit from the status quo. That’s part of the legacy of Black power.

Check out more sessions in the SNCC Legacy Project’s SNCC & Grassroots Organizing series.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn