By Jesse Hagopian

With a short video and readings with competing viewpoints, students will learn about master narratives and counter-narratives and how they apply to Rosa Parks’ life. This activity can be introduced before watching the film or reading the book, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks.

Introduction

Rosa Parks is one of the best known, yet least understood, figures in U.S. history. Parks’ defiance of the Jim Crow laws of Montgomery, Alabama, when she rode the bus on December 1, 1955, is legendary. As Dr. Jeanne Theoharis wrote in A More Beautiful and Terrible History, “When asked to name a ‘most famous American’ other than a president ‘from Columbus to today,’ high school students most often chose Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks.” However, along with Parks’ canonization has come a softening of what she fought for, omissions in her lifetime of work in the Black Freedom Struggle, and a master narrative that uses her story to represent ceaseless American progress. As Theoharis says about King and Parks, “These two freedom fighters have been turned into Thanksgiving parade balloons — floating above us larger than life; unthreatening, happy patriots. Asking little of us, they bob along proud of our progress.”

Many across the ideological spectrum embrace Rosa Parks — at least a distorted version of her memory. So many of the popular accounts of Parks imagine her as an accidental heroine, a quiet seamstress, simply too tired to move from her seat on the bus that fateful day. Even accounts of Parks’ life that reject that deeply problematic narrative often omit the fact that she was not only a lifelong activist, but also a political strategist, an organizer against sexual violence, a supporter of the Black Power movement, an admirer of Malcolm X, a believer in Black people’s right to self-defense, and so much more.

When Mrs. Parks died on October 24, 2005, congressional leaders on both sides of the aisle rushed to pay tribute to the “mother of the Civil Rights Movement.” Republican Condoleezza Rice said at the public viewing of Parks’ body in Montgomery, Alabama, “Without Mrs. Parks, I probably would not be standing here today as Secretary of State.” Republican Senate majority leader Bill Frist attended the Washington, D.C., ceremony with Parks’ coffin lying in honor at the Capitol rotunda and said Parks’ defiance of Jim Crow laws was “not an intentional attempt to change a nation, but a singular act aimed at restoring the dignity of the individual.” Senator Hillary Clinton spoke of the importance of “quiet Rosa Parks moments.” The New York Times described Parks as the “accidental matriarch of the Civil Rights Movement.” Theoharis dispels these master narratives in her book, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks:

The Rosa Parks who surfaced in the deluge of public commentary was, in nearly every account, characterized as “quiet,” “humble,” “dignified,” and “soft-spoken,” she was “not angry” and “never raised her voice.” Her public contribution as the “mother of the movement” was repeatedly defined by one solitary act on the bus on a long-ago December day and linked to her quietness. Held up as a national heroine but stripped of her lifelong history of activism and anger at American injustice, the Parks who emerged was a self-sacrificing mother figure for a nation who would use her death for a ritual of national redemption.

The narrative of national redemption that was constructed around Parks erased the truth about her life and the broader Black Freedom Struggle. It concealed the fact that she and others had worked for years before the bus boycott in struggles for racial justice that were critical to the boycott’s eventual success. The master narrative telling of Parks’ life is used to denigrate struggles for racial justice today suggesting that in the United States, the way to undo injustice is to be quiet and patient and the problem will be resolved. This distorted telling of her life ignores, in the words of Theoharis, “her 40 years of political work in Detroit after the boycott, as well as the substance of her political philosophy, a philosophy that had commonalities with Malcolm X, Queen Mother Moore, and Ella Baker, as well as Martin Luther King Jr.”

This lesson is designed to help students understand the master narratives they have been taught about Rosa Parks. They will also learn counter-narratives that can help them not only better understand her life, but also glean lessons for the struggles for racial and social justice today.

Myles Horton, second from left, and Rosa Parks, third from left, are among a group meeting at the Highlander Library in Monteagle, Tenn. Undated. Nashville Banner Archives, Nashville Public Library.

Suggested Procedure

1. Activate Prior Knowledge

A. Asks students to share what they already know or have previously learned about Rosa Parks. Assuming your classes have not already studied her life in depth, you can expect basic answers such as:

-

- “She was arrested for not giving up her seat to a white man.”

- “She was a quiet seamstress who refused to give up her seat on the bus.”

- “She was a Black women activist who helped spark the Civil Right Movement when she was arrested on a bus for refusing to give up her seat to a white man.”

B. As a follow-up question — assuming most students predominantly know only about the one moment in her life when she was arrested for not giving her seat to a white man — ask the class: “Why do most of us in the class not know very much about Rosa Parks before or after that moment on the bus?”

C. A final question to set up this lesson is: “What more would you want to learn about Rosa Parks to understand her life more fully?”

2. What Is A Master Narrative?

A. Hand students the following definitions of a master narrative:

Master narrative is defined as the social mythologies that mute, erase, and neutralize features of racial struggle in ways that reinforce ideologies of White supremacy. — Professor Ashley N. Woodson

The master narrative is a set of historical fictions and sanitized images that distort the power and promise of grassroots organizing. — Professor Julian Bond

The master narrative is whatever ideological script that is being imposed by the people in authority on everybody else. — Toni Morrison

Talk with students to clarify the key ideas in this definition: What are “social mythologies”? What is an “ideological script”? What does it mean to “mute, erase, and neutralize features of racial struggle”? What is “White supremacy”?

For background for the teacher on the “master narrative” or a longer reading for students, see The View from the Trenches by Charles Payne.

B. Next, provide students a copy of the following paragraph from Dr. Jeanne Theoharis about the master narrative of Rosa Parks’ life:

The Rosa Parks who surfaced in the deluge of public commentary was, in nearly every account, characterized as “quiet.” Humble,” “dignified,” and “soft-spoken,” she was “not angry” and “never raised her voice.” Her public contribution as the “mother of the movement” was repeatedly defined by one solitary act on the bus on a long-ago December day and linked to her quietness. Held up as a national heroine but stripped of her lifelong history of activism and anger at American injustice, the Parks who emerged was a self-sacrificing mother figure for a nation who would use her death for a ritual of national redemption.

C. In small groups, ask students to discuss these two short readings together. Invite students to consider to what degree the answers they provided earlier about what they know about Rosa Parks reflect this master narrative.

3. What Is a Counter-narrative?

A. Provide students the following definition of a counter-narrative from the Center for Intercultural Dialogue:

Counter-narrative refers to the narratives that arise from the vantage point of those who have been historically marginalized. The idea of “counter-” itself implies a space of resistance against traditional domination. A counter-narrative goes beyond the notion that those in relative positions of power can just tell the stories of those in the margins. Instead, these must come from the margins, from the perspectives and voices of those individuals. A counter-narrative thus goes beyond the telling of stories that take place in the margins. The effect of a counter-narrative is to empower and give agency to those communities. By choosing their own words and telling their own stories, members of marginalized communities provide alternative points of view, helping to create complex narratives truly presenting their realities.

B. Now tell students they are going to examine three counter-narratives about Mrs. Parks. First, ask them to listen to a short audio clip from Jeanne Theoharis. Next, ask them to read this paragraph from Bill Bigelow’s article, “Teaching the Radical Rosa Parks.”

. . . although surveys have indicated that Mrs. Parks may be the most famous woman in 20th-century U.S. history, in the conventional curriculum and popular imagination, she remains “trapped on the bus.” She also remains trapped in the myth of the lone, tired seamstress who changes the world. Her life was much more than the moment when she refused to give up her seat when ordered to move by a white bus driver in Montgomery, Alabama. Mrs. Parks’ life is a tapestry of resistance. And, indeed, she spent more than half her life in Detroit — which Mrs. Parks called “the Northern promised land that wasn’t” — fighting segregation in housing, hospitals, and restaurants; protesting police murders of Black teenagers; organizing against sexual violence; working for Congressman John Conyers and getting to know Malcolm X. Rosa Parks’ life offers a road map from the Civil Rights Movement to Black Lives Matter and #MeToo.

Finally, there is a one-line quote by Parks.

The only tired I was, was tired of giving in. — Rosa Parks

C. In small groups, ask students to summarize key elements in the counter-narrative of Mrs. Parks’ life emphasized by Theoharis, Bigelow, and Mrs. Parks herself.

4. Identifying Master Narratives and Counter-narratives on Screen and in Print.

Tell students you will be showing them a short video (from Twinkl Teaching Resources) about Mrs. Parks. Do not give them any more information about the content of the film. Ask students to look for evidence of either master narratives or counter-narratives, and to write down what they see and hear.

After viewing the video clip, invite students to discuss the evidence they gathered from the video clip of master narratives or counter-narratives about Parks.

Share with students Ten Ways to Teach Rosa Parks by Jeanne Theoharis and Say Burgin. As before, ask students to highlight the counter-narratives.

5. Final Reflection Question

Ask students: “To what extent do you agree with Jeanne Theoharis when she said, ‘Rosa Parks is arguably one of the most celebrated Americans of the 20th Century and arguably one of the most distorted and misunderstood.’?”

Encourage students to incorporate what they have learned about master narratives and counter-narratives into their conversation.

Follow Up

As a follow up to this lesson, students should watch the entire film The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks. As they watch, students can make a list of the master narratives the film challenges and the counter-narratives it offers.

More Lessons

This lesson is from the The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks Teaching Guide, a collection of lessons to accompany the book and film of the same name.

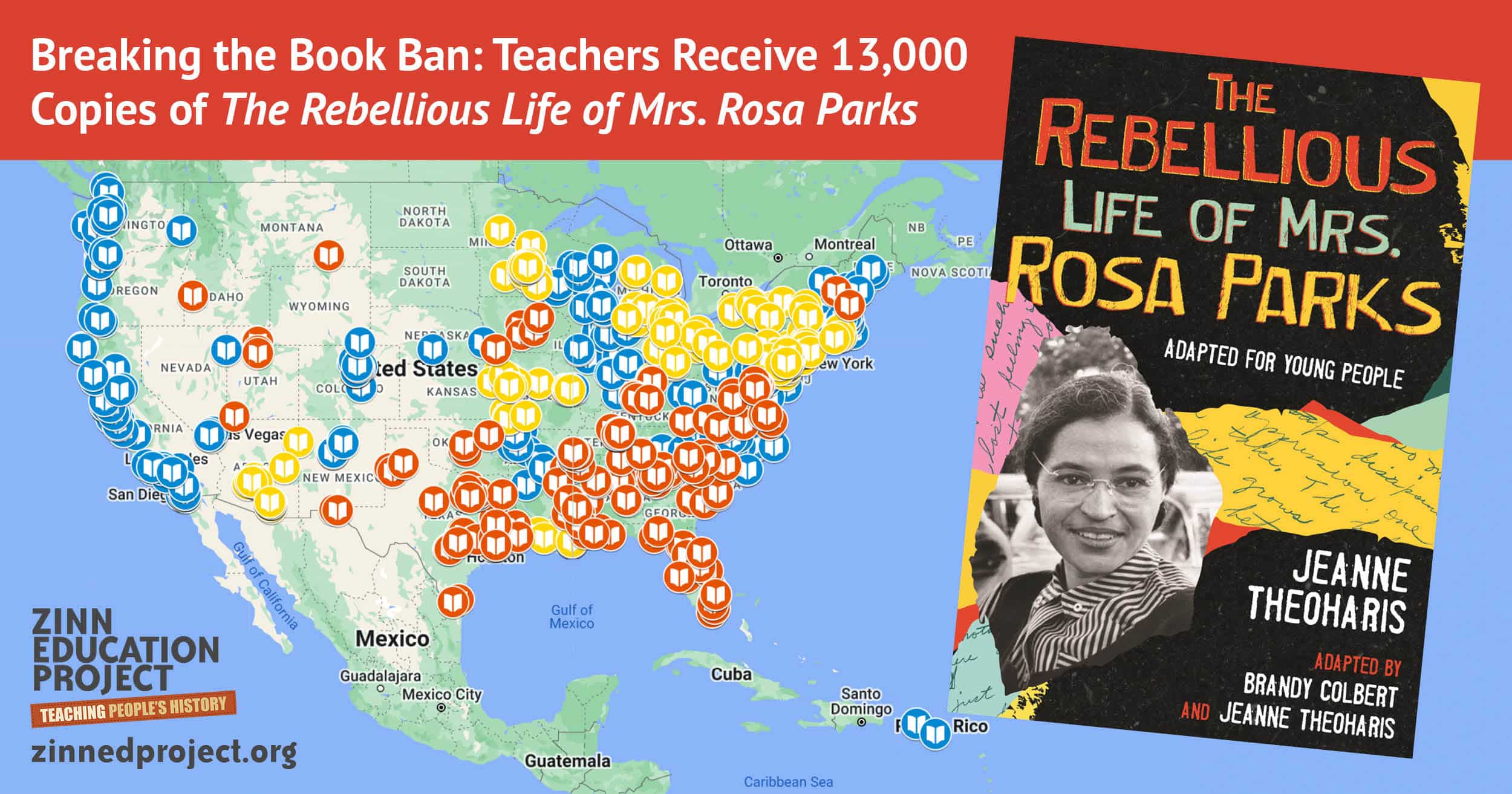

Feedback Requested

Most of the lessons, including this one, have yet to be field tested. Therefore, they are posted as Google docs and will be revised once we hear back from teachers about the implementation. Please share your feedback — what worked, what didn’t, student responses, adaptations, and more. We will send you copies of the young readers edition of The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks and other resources in appreciation. We look forward to hearing from you.

Credits and Permissions

Jesse Hagopian is a U.S. history teacher, an editor for Rethinking Schools magazine, and is the editor and co-editor of a number of books including More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing and Teaching for Black Lives. He is on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project. Read more.

The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks Teaching Guide, book distribution, and educator film screenings are made possible by Soledad O’Brien Productions and funded by The Ford Foundation.

Permission is offered to use this lesson in the classroom. It should not be posted elsewhere online nor reprinted.

This lesson is from the The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks Teaching Guide for classroom use. It is part of a collection of lessons to accompany the book and film of the same name.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn