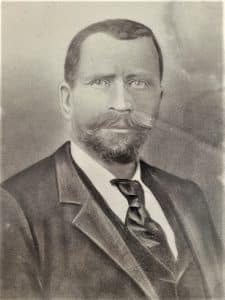

This photo of Walter H. Williams is courtesy of Beverly Babin Woods.

On Feb. 3, 1868, the Louisiana Superintendent for Education in the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands appointed African-Canadian immigrant Walter H. Williams to open and teach in a Freedmen’s Bureau School in Lafayette Parish, Louisiana. With that appointment, Williams became the first Black educator employed to teach in the region by the Freedmen’s Bureau.

Williams was born in Ontario, Canada, in 1844. His parents, Reason and Mirinda (Brady) Williams, were from Virginia. They settled near Toronto in 1825. The couple never returned to the United States. Two of their sons, Walter H. and his brother Moses B. moved to the United States at the end of the Civil War to take part in Reconstruction and Republican politics. In 1868, Walter Williams was appointed to teach in Louisiana as a federal employee under the Freedmen’s Bureau. His brother, Moses, also a teacher, joined him there in 1872.

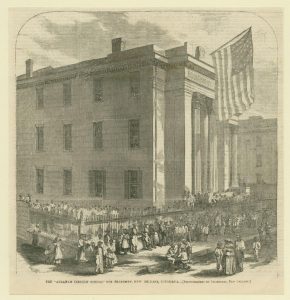

The 1868 Federal Law, under the Constitution, called for integrated schools. However, Louisiana resources were not directed to support public education and there were no local resources to fund public schools, so the Freedmen’s Bureau provided a stop-gap measure. The Bureau schools were intended to serve non-white constituents while the state reorganized its education services under the Constitution.

By the fall of 1868, Williams established himself in Louisiana. In 1872, he married Pearl Gennieve Doucet, the daughter of Jouchan and Delia (Michel) Doucet. He taught over 40 pupils in his classroom. Unfortunately, the Freedmen’s Bureau struggled to fund education in the south. Despite the enthusiasm liberated Louisianans had for their children’s education and their own night schools, the fear of white terrorism and lack of funding created stumbling blocks for Williams’ efforts. In a report to his supervisor, Williams wrote that he struggled against white indifference and lack of support from the state:

There are no Boards of Education to whom I can apply. With parents and pupils, the will to be educated can be exciting, but not the will to support the necessary schools. . . while the sentiment of the colored people is generally in favor of education, though there is a general feeling among them that their schools ought to be free, the impression is general among them that free schools will soon be opened.

In summer 1873, the state constitution’s promise of public schools was fulfilled and Williams was appointed to teach for the Lafayette Parish Public School Board. Genealogist Beverly Babin Woods, Walter H. Williams’ great-granddaughter and a historical researcher, describes their appointments as “successfully bridging federal and local government in support of public education.” She writes of her ancestors:

Despite the many threats and hardships, Walter Williams and his brother Moses had many successes. . . the largest attendance records in 12 Wards. . . enhanced by the ability of the two brothers to speak both French and English, thus enabling them to communicate more effectively with their French and Creole constituents in Louisiana.

Walter H. Williams taught in public and private schools full-time in Louisiana until the mid-1880s. Afterward, he entered a career as a public servant at the U.S. Custom House at the Port of New Orleans. Williams and his wife had seven children together, and their descendants live throughout the United States and Canada. Walter H. Williams’ story was uncovered by Ms. Woods, who understood his national significance and offered her research to the Zinn Education Project. We present it here with her permission and ask that any citation of this post be credited to her research.

Learn more in the Zinn Education Project national report, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction,” and find teaching resources on Reconstruction below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn