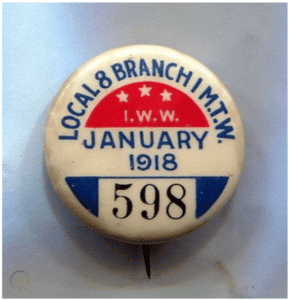

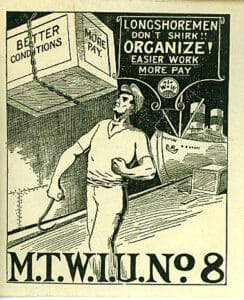

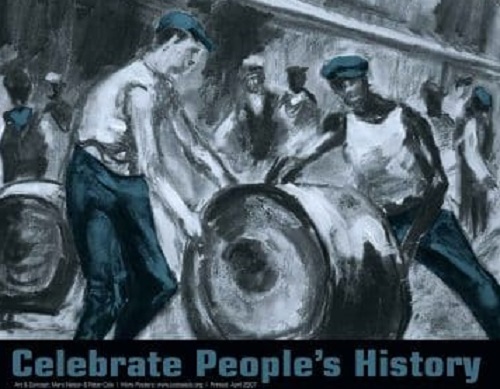

On May 14, 1913, more than four thousand Philadelphia longshoremen, who loaded and unloaded ships, went on strike and shut down one of the busiest ports in the United States. During their two-week strike, they joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a revolutionary union deeply committed to racial equality and socialism. As members of Local 8 (of the IWW’s Marine Transport Workers industrial union), they were led by Ben Fletcher — a brilliant organizer, humorous speaker, and the most prominent African American in the IWW.

On May 14, 1913, more than four thousand Philadelphia longshoremen, who loaded and unloaded ships, went on strike and shut down one of the busiest ports in the United States. During their two-week strike, they joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a revolutionary union deeply committed to racial equality and socialism. As members of Local 8 (of the IWW’s Marine Transport Workers industrial union), they were led by Ben Fletcher — a brilliant organizer, humorous speaker, and the most prominent African American in the IWW.

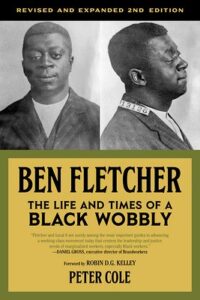

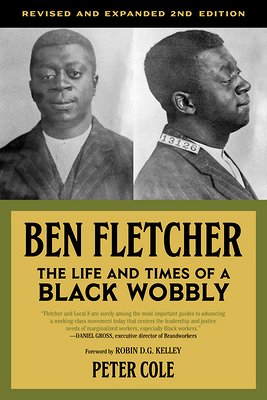

Born in Philadelphia in 1890 to parents probably born enslaved in Virginia, Fletcher’s life both was typical of the Black experience and quite atypical. Fletcher helped lead a groundbreaking union that quite possibly was the most diverse and integrated organization — not simply union — in an era rampant with racism, anti-unionism, and xenophobia. At its founding, Local 8’s membership was roughly one-third African American, one-third Irish and Irish American, and one third European immigrant (particularly Italians, Poles, East European Jews). Hence, they fit perfectly into the IWW which welcomed people of color, in keeping with their emphasis on class solidarity and their motto: “An Injury to One Is an Injury to All!”

Local 8 proved to be the IWW’s most successful effort at organizing a multiracial, multiethnic workforce, as well as becoming one of its most durable branches — basically controlling waterfront labor for a decade. Local 8 also integrated work gangs (what might be labeled “integration from below”) and social events, as well as mandated equal racial representation among elected leadership. In fact, the IWW had been founded in 1905 in part because mainstream US labor unions, generally affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), refused to organize most Black, female, immigrant, or “unskilled” workers.

Local 8 proved to be the IWW’s most successful effort at organizing a multiracial, multiethnic workforce, as well as becoming one of its most durable branches — basically controlling waterfront labor for a decade. Local 8 also integrated work gangs (what might be labeled “integration from below”) and social events, as well as mandated equal racial representation among elected leadership. In fact, the IWW had been founded in 1905 in part because mainstream US labor unions, generally affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), refused to organize most Black, female, immigrant, or “unskilled” workers.

Fletcher was celebrated by the most prominent, radical Black intellectuals of his day. A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen, co-editors of The Messenger, a socialist monthly published in Harlem that billed itself as the “only radical Negro magazine in America,” regularly praised Fletcher and Local 8. In 1923, Fletcher was described as “the most prominent Negro Labor Leader in America.”

Fletcher appreciated and embodied the notion that only worker power — at the point of production — could usher in a new society, worldwide. He knew, from personal and union experiences, that doing so demanded, first, obliterating the color line. Local 8 built the sort of durable, diverse union which supported workers’ immediate needs while advocating for working-class solidarity and socialism. To quote John Lennon, Fletcher was a working-class hero who led an interracial, predominantly Black labor union. His story is as relevant today as a century ago.

Fletcher appreciated and embodied the notion that only worker power — at the point of production — could usher in a new society, worldwide. He knew, from personal and union experiences, that doing so demanded, first, obliterating the color line. Local 8 built the sort of durable, diverse union which supported workers’ immediate needs while advocating for working-class solidarity and socialism. To quote John Lennon, Fletcher was a working-class hero who led an interracial, predominantly Black labor union. His story is as relevant today as a century ago.

This entry is by Peter Cole, professor of history at Western Illinois University and the author of Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly, Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area, and Wobblies on the Waterfront: Interracial Unionism in Progressive-Era Philadelphia. Twitter: @profpetercole

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn