This post was adapted from articles at the Historic, Art, & Archives website of the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate’s Art & History resource.

On April 20, 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Ku Klux Klan Act, which enforced the 14th Amendment by guaranteeing all citizens of the United States the rights afforded by the Constitution and providing legal protection under the law.

This bill was intended to counter violent white supremacist backlash against the protections affirmed by the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution that extended civil and legal protections to formerly enslaved citizens and prohibited states from disenfranchising voters “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

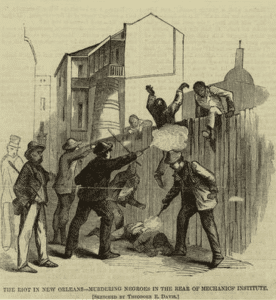

White supremacists, including organized members of the Ku Klux Klan, terrorized Black Americans for exercising their right to vote, running for public office, and serving on juries. In response to the violent unrest and suppression of civil liberties, Congress passed a series of Enforcement Acts in 1870 and 1871. Among other protections, it empowered the president to use military force to protect African Americans.

The Ku Klux Klan Act was the third of the “Enforcement Acts” passed during Reconstruction to defend the rights of Black citizens. The first reinforced the Fifteenth Amendment (universal manhood suffrage). The second act placed all southern elections under federal control. The third protected the voter registration and justice system from infiltration and intimidation by Klansmen.

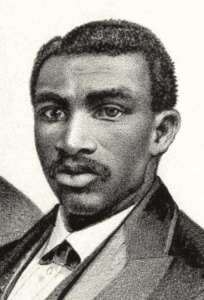

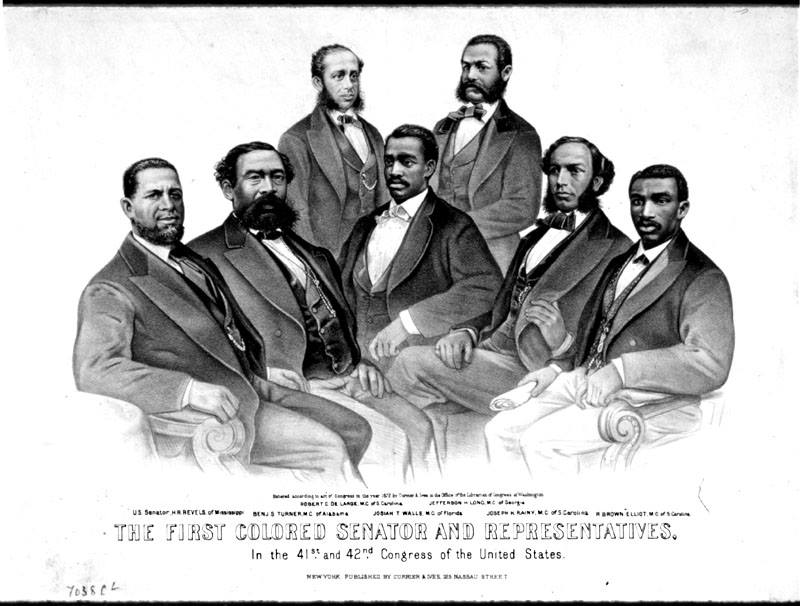

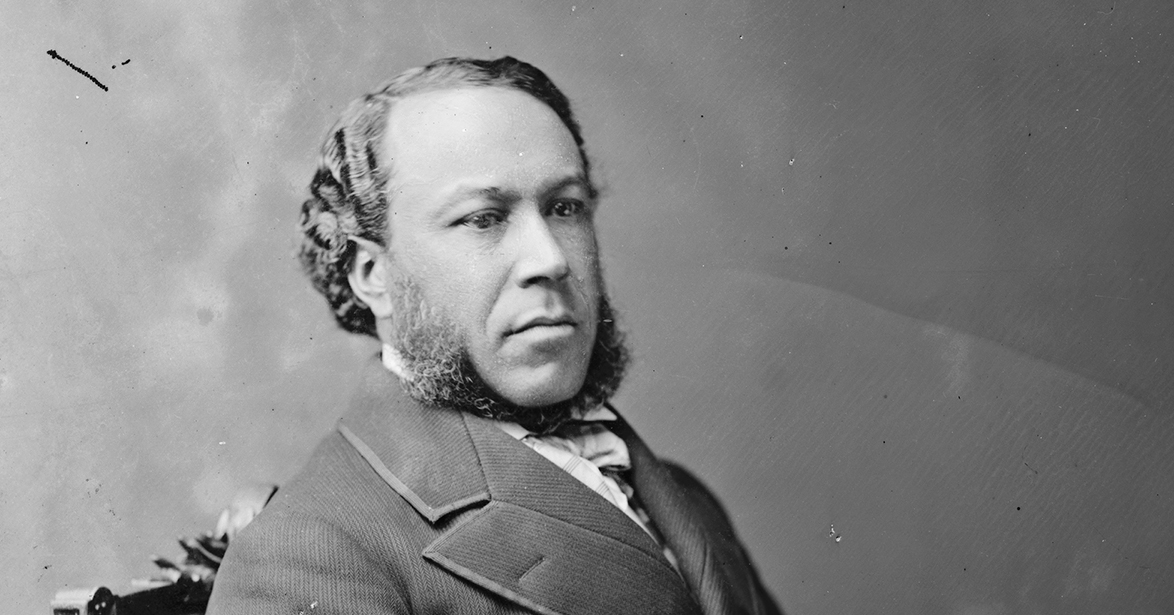

The six Black members who served in the Congresses in which these bills were considered and whose elections were marred by extrajudicial violence nearly universally supported the legislation. Congressman Robert Elliott of South Carolina rallied his white colleagues to support the third act:

If you cannot now protect the loyal men of the South, then have the loyal people of this great Republic done and suffered much in vain, and your free Constitution is a mockery and a snare.

The Enforcement Acts authorized the President to intervene in the former rebel states that attempted to deny “any person or any class of persons of the equal protection of the laws, or of equal privileges or immunities under the laws.” To take action against this newly defined federal crime, the President could suspend habeas corpus, deploy the U.S. military, or use “other means, as he may deem necessary.” Opponents denounced the bill as an unconstitutional attack on state governments and individual liberty. . . . Nearly six months later, in October 1871, Grant used these powers in several South Carolina counties, demonstrating the willingness of the Republican-led federal government to take decisive action to protect the civil and political rights of the freed people during Reconstruction.

Historian and Teach Reconstruction campaign adviser Stephen West offers several Twitter threads about the Act’s history and its legacy.

The new act strengthened anti-conspiracy provisions in the May 1870 Enforcement Act and permitted individuals to sue state officials for violating their rights under the US Constitution.

It also authorized the president to suspend the writ of habeas corpus to suppress terrorism. pic.twitter.com/QdsPmpb6BE

— Stephen West (@Stephen_A_West) April 20, 2021

The Act remains relevant today.

This suit is based on the Third Enforcement Act, aka the Ku Klux Act, passed by Congress 150 years ago this April, to combat white supremacist terrorism during Reconstruction. https://t.co/Pke5xcUO5f

— Stephen West (@Stephen_A_West) February 16, 2021

Read more about the Enforcement Acts at West’s #OTD thread.

Learn more in the Zinn Education Project national report, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction,” and find teaching resources on Reconstruction below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn