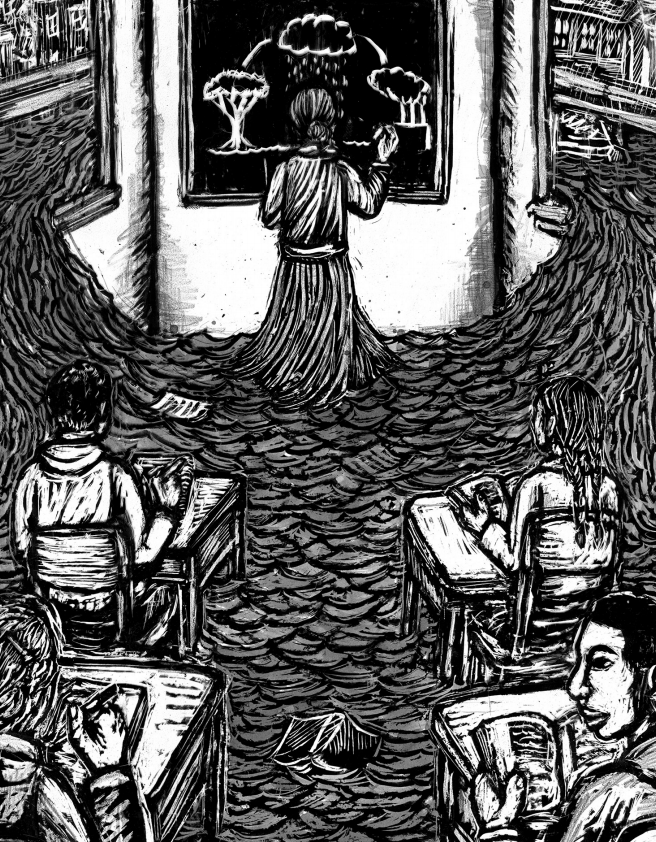

Classroom filling up with water. Source: Rethinking Schools/Erik Ruin.

The climate justice resolution passed on May 17, 2016, by Portland, Oregon’s school board was the country’s first such comprehensive resolution. From the beginning of our work on the climate justice resolution, the group of parents, teachers, students, and community activists who began meeting in December 2015 hoped that not only would we convince Portland’s school board to chart a new course in climate change education, but that we might seed similar efforts around North America.

Below, Portland’s Educating for Climate Justice, the organization that initiated this effort, offers some thoughts on what contributed to our successful effort as well as some of the things that we’d do differently were we starting over. We hope these will be of use to individuals or organizations considering their own efforts to transform climate education in the schools.

Start broad, go slow, involve educators and non-educators.

The idea for the climate justice resolution grew out of a workshop that the local 350.org affiliate, 350 PDX, sponsored in November 2015, led by Bill Bigelow and Tim Swinehart, on the Rethinking Schools book, A People’s Curriculum for the Earth. One of the essential questions of the workshop was “How can teachers and activists collaborate to strengthen climate justice education in schools?” Earlier in the year, Portland’s city council had passed a resolution putting the city on record as opposing the use of any city funds to support the development of fossil fuel infrastructure.

The idea for the climate justice resolution grew out of a workshop that the local 350.org affiliate, 350 PDX, sponsored in November 2015, led by Bill Bigelow and Tim Swinehart, on the Rethinking Schools book, A People’s Curriculum for the Earth. One of the essential questions of the workshop was “How can teachers and activists collaborate to strengthen climate justice education in schools?” Earlier in the year, Portland’s city council had passed a resolution putting the city on record as opposing the use of any city funds to support the development of fossil fuel infrastructure.

This successful measure highlighted the possibility of similar community-initiated resolutions that could contribute to climate justice. In the workshop, one of the materials shared was a textbook, Holt McDougal’s Modern World History, the sole adopted textbook in a course taken by almost all Portland high school students. The book includes a mere three paragraphs on climate change; the second paragraph of the Modern World History edition Portland uses begins, “Not all scientists agree with the theory of the greenhouse effect.” Workshop participants, especially those unfamiliar with this text, were horrified. We decided to meet again to talk about how we could challenge inaccurate materials and help institute a more robust climate justice curriculum into Portland’s schools.

We sent invitations for an inaugural meeting to teachers, 350 PDX activists, and other individuals we knew had a concern for climate justice in the schools. In retrospect, we could have made an even broader call, to make sure that we had the widest participation possible from concerned community, social/environmental justice, and education activists. But our small(ish) numbers—meetings ranged from a low of 8 to a high of 26—allowed for democratic participation and people who had not worked together getting to know one another.

Draft a quality resolution.

We didn’t rush the resolution-drafting. Every meeting began with a read-around of the current draft followed by a point-by-point discussion and word-smithing. By the time we were ready to bring the resolution to the school board, it had been thoroughly reviewed.

Make an argument for climate justice.

We knew from the start that our resolution wouldn’t focus simply on teaching accurate climate science in Portland’s schools, but would also advocate for the necessity of climate justice education. For this reason, we included language in the resolution that calls for students to investigate the root causes of the climate crisis, as well as for the involvement of people from “frontline communities” to help the district create and implement a curriculum that adequately addresses the human dimensions of climate change.

As important as it is for students to understand the science (and the scientific consensus) around human-caused climate change, it is arguably even more important for them to understand the social dimensions of the crisis and to be familiar with the stories of the people around the globe who are fighting to transform the unjust economic and political structures at the root of the crisis. Several of the climate education policies that have already been adopted in cities and states around the country (New York and California, for example) focus exclusively on teaching accurate climate science—and while we applaud these policies as an important place to start, they risk leaving students overwhelmed with the knowledge that a crisis exists, but without the necessary understanding and tools to see themselves as part of a global movement to effect meaningful change.

Build support before going public.

Individuals in the group volunteered to take the resolution to education, environmental, social justice, labor, student, and religious groups and organizations for endorsement. In some cases, organizations or other individuals had reservations and suggested rewording, which we reviewed in our group and made changes accordingly. We ended up with more than 30 organizational endorsements. Members from a number of these groups joined us when we eventually presented the resolution before the school board. Even though we secured a large number of endorsements, it would have been good for us to have been somewhat more systematic about this than we were, and not to have begun the process with the school board prior to making sure that we had secured all the endorsements possible. As much as possible, our aim was to have this resolution “owned” by the community, rather than just by the group doing the actual drafting.

Seek support from sympathetic school board members.

School boards vary from community to community but becoming familiar with school board procedures and the dispositions of different members is crucial to a successful campaign. We were fortunate to have a member of the Portland school board, Mike Rosen, who reviewed the resolution, made suggestions, and met with our committee to discuss the best process to introduce the resolution to the school board. Rosen got us on the agenda of the appropriate school board committee for a presentation, then for an additional presentation before the full board, prior to the final meeting where the resolution was formally introduced and voted on. We had reached out to him early in the process, so that by the time the resolution arrived at the final school board meeting, it was really his resolution, too.

We should have made greater efforts to reach out to all the members of the school board. We had contacted a couple of other board members individually, and we presented before the Teaching and Learning Committee of three board members, but we had not “lobbied” very intensively. (The school board includes seven members, elected citywide.) In the end, this did not matter, as the vote was unanimous, but were we to do this again, this is a piece of our organizing we might have given more attention to. It also could have been a way to involve other community members prior to the final board hearing and vote.

Make school board consideration of the resolution a community event.

We were at somewhat of a disadvantage because the school board meeting we were scheduled for was preceded by a big budget hearing, beginning at 6 pm, and we were told that it could last several hours before the formal school board meeting would begin. So we did not know exactly when to tell our supporters to arrive. Nonetheless, we wanted to make this a community event as much as possible, and so put out an invitation for people to show up wearing red—the anti-fossil fuel solidarity color worn at coal-export and oil-terminal hearings in the Portland area—at 7 pm.

We sent email blasts to the local Portland Area Rethinking Schools list, 350 PDX, Climate Jobs PDX, the Climate Action Coalition, Raging Grannies, and others. We held a brief but lively rally in front of the high school where the school board was meeting. We planned in advance which of our members would testify to ensure that all important topics were covered. A couple of our members talked about the significance of the resolution, and linked what we were doing to the previous weekend’s “Break Free from Fossil Fuels” events in Anacortes, Washington, where many of our members had gone to demonstrate and where one had been arrested blocking the BNSF rail lines into the Shell and Tesoro oil refineries. We ended with a song—“Singing for the Climate”—shared with us by Bay Area teacher educator and activist Sudia Paloma. Through the evening, we had close to 100 supporters who came by with perhaps 50 or so staying through the final testimony and board vote, which didn’t happen until around 10:30 pm. The vote, as mentioned, was unanimous, and it was greeted by cheers, a standing ovation, hugs, and high fives.

Have a media strategy.

Have a media strategy including identifying in advance who will speak on behalf of your organization and how you will handle any criticism or opposition that might unfold during the process. We did not do a good job of reaching out to the media prior to the introduction of our resolution or immediately after. We’ve been playing catch-up ever since. We simply did not anticipate the vitriol that would come our way from the right wing media. There was an article in the Portland Tribune, published soon after the school board passed the resolution. It contained a number of errors, and also a somewhat inflammatory headline: “Portland School Board Bans Climate Change-Denying Materials.” The resolution does not use the word “ban,” and the Tribune article helped shape the right wing media critique—on Fox News; in the National Review, Washington Times, Glenn Beck’s The Blaze website, Portland’s newspaper The Oregonian, etc.—that Portland was banning books (some more lurid outlets said “burning” books.)

We should have been ready, prior to passage of the resolution, to help interpret what the school board had—and had not—done. One of our members published a piece at Common Dreams, which was also carried by the Huffington Post and AlterNet, but we should have had other articles and letters to the editor lined up prior to passage. As we realized that our side was not being heard in much of the media coverage, we reached out to supporters to generate op-eds and letters to the editor; and others joined in, like the national group Climate Parents, which launched a MoveOn.org thank you petition to the Portland school board.

Solidify one’s base.

We should have immediately communicated the resolution’s passage, and our gratitude, to the many organizations that had endorsed our resolution. Prior to the school board meeting, we should have drafted a thank you letter to send out right away to supporters, explaining the significance of the resolution and asking for supportive letters to the editor, op-eds, and letters to school board members. We were stunned by the suddenness and viciousness of the right-wing attack on the resolution. We anticipated that there would be those who would challenge the theme of climate justice that was at the heart of the resolution. But the Fox News and internet attacks challenged the very idea of human-created climate change.

The right-wing narrative of banning and censorship also led to a misinformed statement put out by the National Coalition Against Censorship. All of these attacks would have been more forcefully countered had we been more prompt in communicating both with the media and with our supporters. Our thank you letter could also have included an invitation to continue supporting the effort, because passage of a school board resolution is only the first of many steps.

Think about implementation from early in the process.

We didn’t want our resolution to be overly prescriptive, as we knew that what was most important was launching a process of community-wide collaboration toward climate justice work in the school district. In the final weeks before formally introducing the climate justice resolution to the school board, we began creating an implementation proposal. This helped us imagine concretely what we wanted the school district to do, and when. We were influenced by ALLY (Asian-Pacific Island Leaders for the Liberation of Youth), which had been working on a tiered proposal to introduce Ethnic Studies courses to all Portland high schools. They articulated specific demands for the phase-in of Ethnic Studies courses over a four-year period. We have just finished a document that indicates our expectations for the implementation of our climate justice resolution over several years, and are beginning formal conversations with Portland Public Schools administrators.

For more information, contact Bill Bigelow (bill@rethinkingschools.org). “Organizing Lessons from the Portland Climate Justice Resolution” was published by Rethinking Schools.

Related News

As Students Clamor for More on Climate Change, Portland Heeds the Call

As Students Clamor for More on Climate Change, Portland Heeds the Call

By Mike Seely, New York Times

PORTLAND, Ore. — The final meeting of the year for the Pacific Islander Club at Roosevelt High School was mostly celebratory, with candy leis for the departing seniors and a spread of fried chicken. But the club was talking climate change, and for many students in North Portland, Ore., the subject hit close to home. Read more.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn