We are saddened by the news that the powerful Ohio organizer and political leader C. J. Prentiss died on April 2, 2024.

We are saddened by the news that the powerful Ohio organizer and political leader C. J. Prentiss died on April 2, 2024.

Our Prentiss Charney Fellowship is named for Prentiss and Michael Charney. Prentiss served in the Ohio State Senate and Charney was a teacher and labor organizer. Married for 40 plus years, they lived in North Kingsville, Ohio, and continued to support social justice causes with a focus on education. When we launched the Prentiss Charney Fellowship, C. J. shared the following quotes and stories about her life.

I see my role as improving the lives of poor folks. Now, I can say improve the lives of African Americans, but I’m real clear on the history. The Civil Rights Movement before that, the suffrage movement before that, our movement against slavery — we empowered everyone; we lifted all over as we zeroed in on the African American challenge. — C. J. Prentiss

Press photo for candidate Carolyn J. Prentiss, Cleveland School Board, 1979. Source: Cleveland Plain Dealer

C. J. Prentiss grew up in Cleveland, Ohio, in an activist family. Her father worked with the Future Outlook League, which was critical in mobilizing the Black community and increasing Black employment. In the 1940s, he was beaten trying to integrate Euclid Beach Park. As noted at the Cleveland Historical website article on the Euclid Beach Park Riot,

Albert T. Luster, a member of the interracial civil rights group the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), was severely beaten by a Euclid Beach Park police officer. Luster was to be one of an interracial group of 10 or so CORE members who, like other groups that summer, sought to test the park’s policies. . . . Discussions soon began in Cleveland City Council that would result in the passage, the following February, of an ordinance that explicitly outlawed discrimination at Cleveland’s amusement parks.

While fighting for justice and driving a city bus, Luster also attended college. After years of study, he received his degrees and began practice as a physician and surgeon. Her mother, Berenice Spaulding Luster, was a science teacher and president of the Cleveland Delta Sigma Theta sorority.

Prentiss credits her parents for laying the foundation for her fight for justice and equality.

Prentiss received both a B.A. in Education and M.Ed. from Cleveland State University, and she holds a post-graduate certificate in Administration from Kent State University. She is also a graduate of the Advanced Management Program at Case Western Reserve University’s Weatherhead School of Management.

Prentiss attended the March on Washington in 1963. In the 1970s, she started the Voter Service Club, where she organized people to register to vote. Then she worked in a fair housing organization.

In her dissertation, Linda M. Trautman explains:

Encouraged by her formative political training and experiences, Senator Prentiss became centrally involved in civil rights groups and political organizations in Cleveland. Most notably, Prentiss was a key player in the civil rights struggle for school desegregation in Cleveland during the late 1970s.

In 1978, a court ordered the desegregation of Cleveland public schools. Prior to this decision, a similar court order was handed down in Boston which precipitated race riots and protests in that city.

Prentiss organized a group called Black Community Leaders for Peaceful School Desegregation. She also became a leader of an interracial political organization called WELCOME (Westsiders and Eastsiders Let’s Come Together), which advocated for racial cooperation and peaceful school desegregation.

Speaking of WELCOME, Prentiss said,

I met my husband Michael Charney. He is white, I am Black and we began to organize the city and have one of the largest bridge walks where the westside and eastside in a walk across the Detroit Superior Bridge [which at that time separated Black and white population in Cleveland]. So that was the beginning of me looking at organizing, politicizing people.

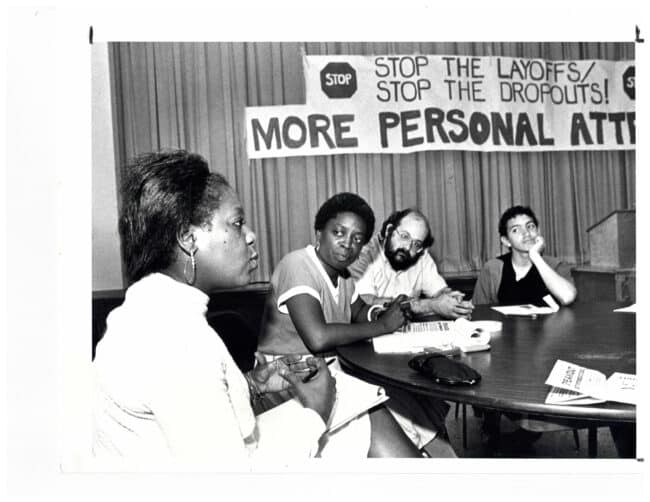

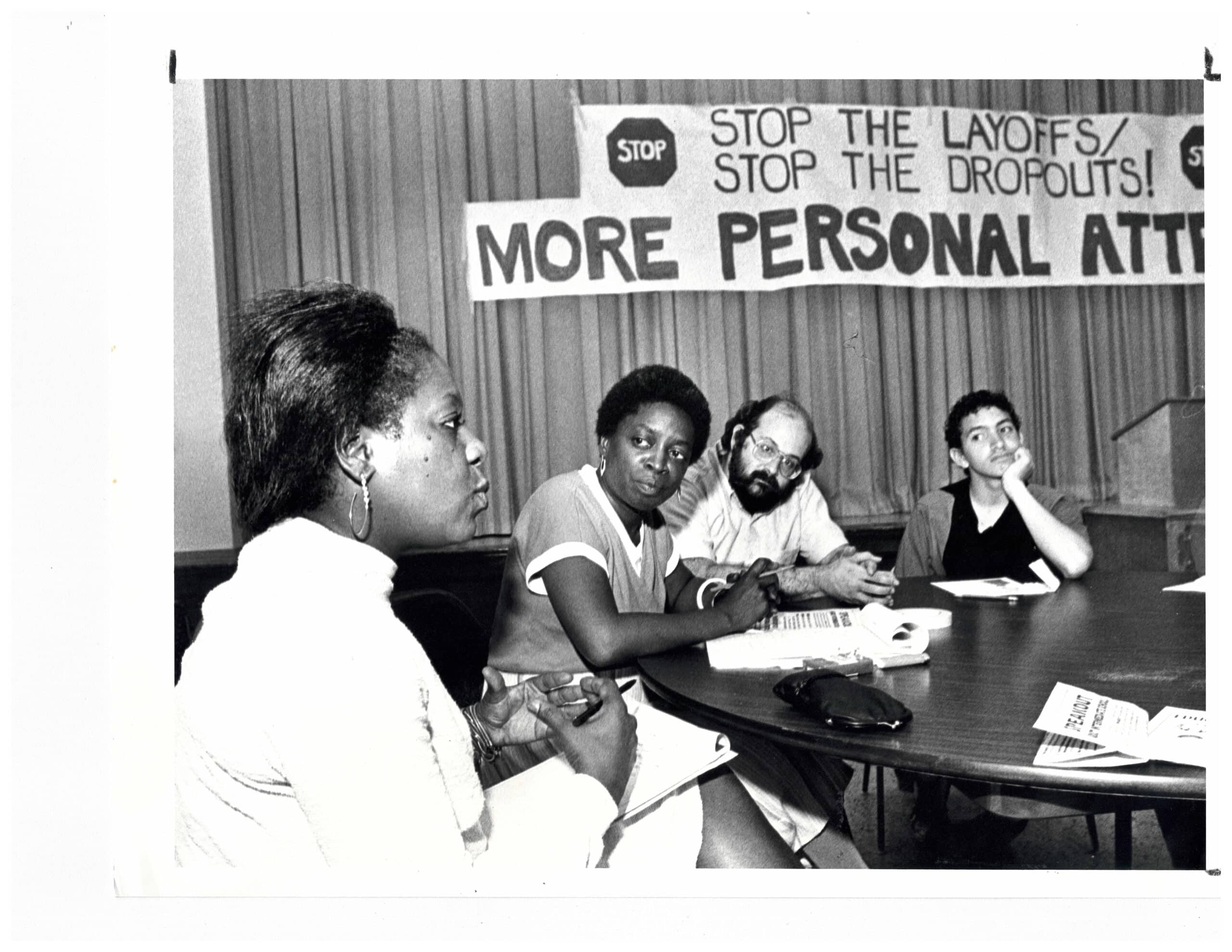

Cynthia Triplett (concerned parent), C. J. Prentiss (school board), Michael Charney (teacher), and Javier Rosa (student) at a public forum on education in Cleveland in 1987. Used with permission of The Plain Dealer.

In 1976, Prentiss was one of the only Black women integrally involved in Ohio’s Cuyahoga Women’s Political Caucus, at the time primarily composed of white women. Next, Prentiss became a delegate to the Democratic Convention for Jesse Jackson in 1984, and then became co-chair of the Cleveland Rainbow Coalition. Prentiss was a teacher for several years before she was elected to the State Board of Education, where she served a six-year term from 1985–1990.

Known in Columbus as “the highest ranking African American education lawmaker in the state of Ohio,” Prentiss served eight years in the Ohio State House of Representatives (8th district) before serving eight years in the Ohio State Senate (21st district). While in the Ohio State Senate, Prentiss represented constituents of Bratenahl, Brooklyn Heights, Cleveland Heights, Cuyahoga Heights, East Cleveland, Newburgh Heights, and University Heights. She served as minority whip (during the 125th General Assembly), Senate Minority Leader in 2005 and 2006, was the first female president of the Ohio Legislative Black Caucus (OLBC), and was the second African American woman to serve as the Democratic leader in the Ohio Senate.

According to Charney, Prentiss “was part of the Squad in the Ohio legislature before there was a Squad.” Speaking of her campaign for state representative, Prentiss said,

When I ran for state representative in 1986, I ran against an incumbent, a Black male who had been a state representative for 18 years. I had absolutely no support from the Black power structure because I was running against one of the old boys. Women rallied around my candidacy.

During the race, Prentiss was attacked for being married to a white man. She lost in 1986 and won in 1990.

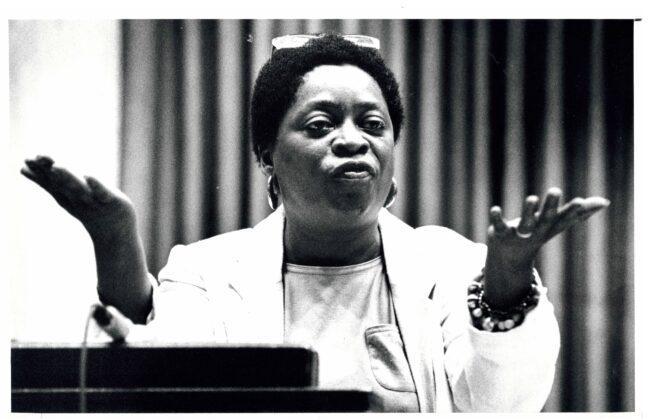

C. J. Prentiss, May 21, 1991. Source: AP

After serving as president of the OLBC, Prentiss became president of the Ohio Legislative Black Caucus Foundation. Under her leadership they traveled to South Africa, where they visited Robben Island Prison where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned and they visited Soweto. The caucus also develops policy and sponsors educational events on behalf of the African American members of the Ohio General Assembly.

She also served as Financial Secretary, was on the Executive Committee of the National Black Caucus of State Legislators (NBCSL), and chaired the Elementary and Secondary Education Committee of the NBCSL. She received special appointments to the Governor’s Blue Ribbon Task Force on Financing Student Success, the Governor’s Commission on Teaching Success, the OhioReads Council, and the Ohio Children’s Trust Fund, among others.

Prentiss was on numerous committees and consistently advocated for those most underserved. She spearheaded significant legislation to decrease the Black-white academic achievement gap, obtained funding for all-day kindergarten and reduced class sizes. She worked tirelessly to improve education for students of all races. Under her leadership, the NBCSL published Closing the Achievement Gap: Improving Educational Outcomes for African American Children, which helped to put the achievement gap on the national agenda.

Prentiss noted the importance of elections for protecting quality education,

[We must] make the defeat of the enemies of education funding a top priority when it’s election time. We need more legislators who believe in public schools and want to work to improve schools. We have many legislators who want to dismantle and privatize education.

Outside of her education initiatives, Prentiss addressed economic issues after the Republican-led senate refused to put a bill on the floor to raise the minimum wage. Prentiss organized a statewide coalition to put the Ohio Minimum Wage Increase Amendment on the ballot in 2006. Voters approved the measure, which led to an increase in the minimum wage in Ohio with further increases each year to make up for inflation.

According to the biography provided at the Ohio State House,

Prentiss challenged her colleagues to have the political will to act now. She believes that without immediate intervention, the future of this generation of young people is one of low self-esteem, prisons, welfare and a widening gap between the have and have nots. . . .

Prentiss has received the Legislator of the Year Award by NBCSL at their Annual Convention 2001 for, among many accomplishments, her work in leading the publication of Closing the Achievement Gap, NBCSL Roundtable Award, Cleveland State Civic Achievement Award, African American Women’s Agenda Woman of the Year Award, Ohio Hunger Task Force Legislator of the Year Award, Greater Cleveland AIDS Taskforce “A Voice Against the Silence” Award, Glenville Hall of Fame Award, and McDonalds Black History Makers of Tomorrow Program Award.

Describing his wife’s courage in the face of bipartisan neglect and indifference, Charney said,

They got a free breakfast program for kids, and it passed in the House again, but the Senate wouldn’t give them money. So, C. J. decided to go on a hunger strike.

She went on a hunger strike particularly for poor Appalachian communities, since the cities were going to pay for the breakfast program anyway.

It lasted like 10 days. She got 20 or 30 other well-known leaders around the state to also go on the hunger strike. And she won.

What that captures is her commitment to not only Black empowerment, but also to all people who are marginalized.

Charney shared in a speech that Prentiss’s influence extended to the Reconstruction Amendments,

C. J. is one of the only people living who voted to ratify the 14th Amendment. How could that happen? She was a senator in the Ohio General Assembly, and somehow someone discovered Ohio never ratified the 14th Amendment. So, they had a vote. She voted for the 14th Amendment [in 2003]. We live in Cleveland and she worked in Columbus, and when she came back she told me what happened, and I said, “What was the vote?” One person voted against it. Ironically, his wife is now in the Ohio General Assembly, and she’s the lead sponsor of one of those laws that says you’re going to lose your teacher’s license if you teach about racism.

After retiring from the Ohio Senate in 2006, Prentiss and Charney helped to found the nonpartisan economic policy research institute Policy Matters Ohio in 2000, which “creates a more vibrant, equitable, sustainable and inclusive Ohio through research, strategic communications, coalition building and policy advocacy.”

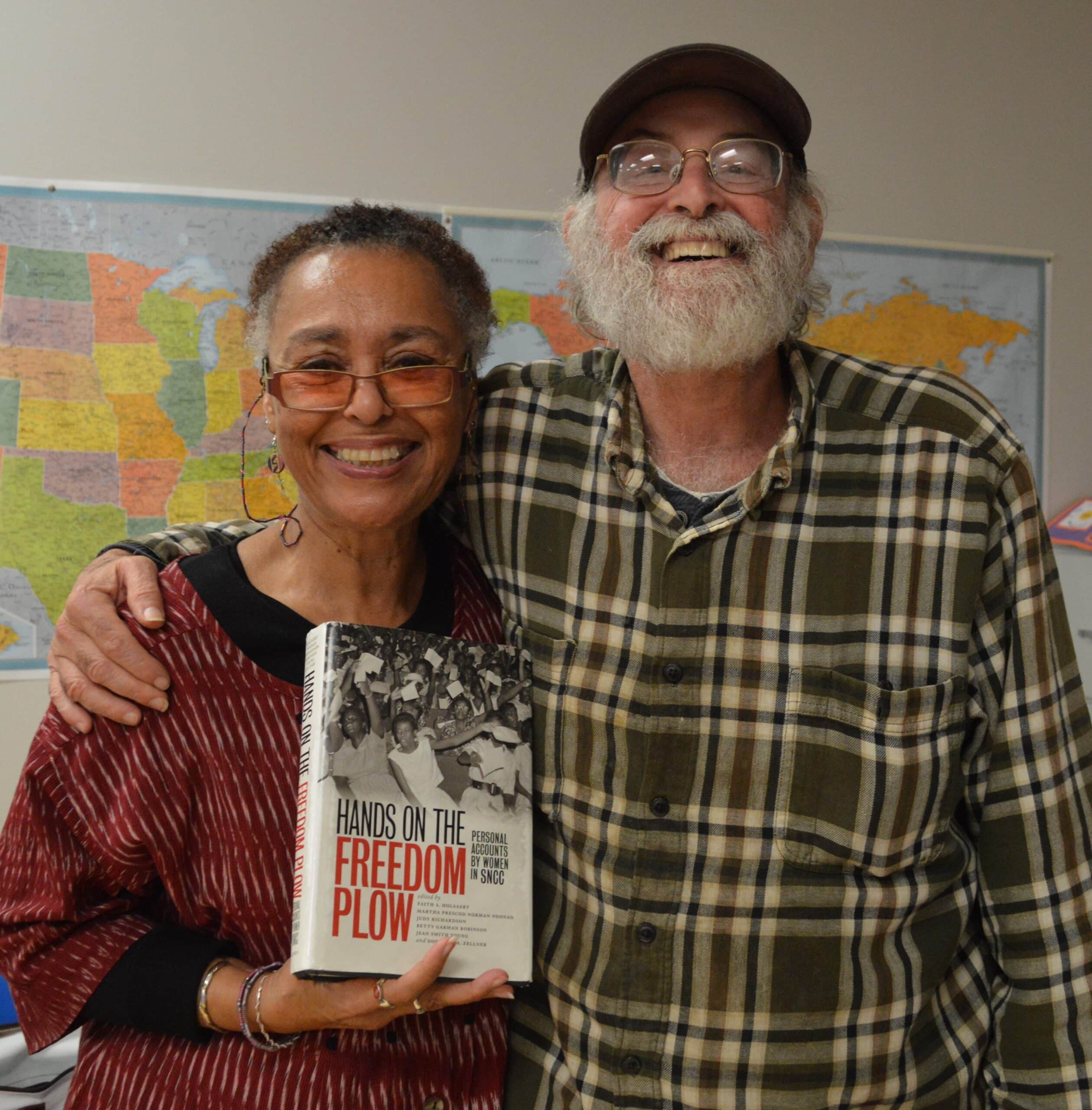

C. J. Prentiss and Michael Charney, at a musical about Reconstruction, at a church in Baltimore. September, 2019. Photo by Deborah Menkart.

Prentiss also developed a program to raise the high school graduation rate of Black boys. Most of the 33 targeted high schools showed significant progress. Because of her work raising the African American graduate rate, Prentiss was picked to be the Special Education Adviser to Ohio Governor Ted Strickland in 2007.

In retirement, she created the C. J. Prentiss Emerging Leaders Project to hone the skills of progressive Ohio leaders under 40. Alumni include Lauren Groh-Wargo, campaign manager for Stacey Abrams, Nsé Ufot of the New Georgia Project, and elected leader Nina Turner. She was also a devoted member of Hiawatha Church of God and Christ.

As Prentiss said in an interview with Rethinking Schools about the fight to close the achievement gap,

Everybody has a role — we must share the responsibility and act. It’s not just about principals and teachers, but the kids, the parents, the church, the business community, the social service community — everyone needs to be a part of this to make it happen.

She organized to improve the lives of those around her, and in doing so, Prentiss’ life serves as model for the Prentiss Charney Fellows.

Prentiss and Charney spoke to the inaugural cohort of Prentiss Charney Fellows in October of 2022. One of the fellows, Tiffany Mitchell Patterson, moderated a 30-minute conversation with them. In closing, Prentiss said:

I am honored that you would agree to participate as Prentiss Charney Fellows. You look at what is going on and you say, “Is there going to be a turnaround?” And you all are that turnaround. You are the hope that I envisioned.

May we continue to carry forward Prentiss’s fierce dedication to quality education for all children with her capacity to bring out the best in her peers.

In memory, contribute to the Prentiss Charney Fellowship.

Donate and indicate in the memo that it is in honor of C. J. Prentiss.

Michael Charney’s Remarks

Michael Charney shared the following remarks at C. J. Prentiss’s Funeral on April 13, 2024.

Sometimes at a funeral, the main speaker speaks about the person without knowing anything about the person and just speaks in general terms. Well, my talk will be a little different because I’ve known C. J. for over 45 years, and I’ll give a series of perspectives and anecdotes about her life.

Often, C. J. would begin some of her talks with a poem written by Eloise Greenfield about Harriet Tubman. It goes,

Harriet Tubman didn’t take no stuff

Wasn’t scared of nothing neither

Didn’t come in this world to be no slave

And wasn’t going to stay one either

“Farewell!” she sang to her friends one night

She was mighty sad to leave ‘em

But she ran away that dark, hot night

Ran looking for her freedom

She ran to the woods and she ran through the woods

With the slave catchers right behind her

And she kept on going till she got to the North

Where those mean men couldn’t find her

Nineteen times she went back South

To get three hundred others

She ran for her freedom nineteen times

To save Black sisters and brothers

Harriet Tubman didn’t take no stuff

Wasn’t scared of nothing neither

Didn’t come in this world to be no slave

And didn’t stay one either

And didn’t stay one either

C. J. began a lot of her talks that way. She also would recite — which I will not — “Ain’t I a Woman” by Sojourner Truth, and would sometimes even dress up like Sojourner Truth.

C. J. was born in 1941 on the west side of Cleveland and attended Nathaniel Hawthorne K–H School and John Marshall High School, where she was one of six Black students in her graduating class. I remember a few years ago, when I was organizing students for the Ohio Youth Agenda, and went to John Marshall — [it was] a lot different than when C. J. went there. I walked through the metal detector, was greeted by a policeman who mentioned he was one of my students and was about to retire, and it really made me feel old. But then I looked at the wall of the Hall of Fame of John Marshall and there was C. J., and it made me feel really proud.

When C. J. was growing up she was a member of the St Paul AME Church on the west side, and her mother was so active in the Delta sorority that C. J. was a Deltone, which I guess is like a high school kid getting ready to be a full-time Delta. She was really influenced by her father, Albert Luster, who I never had a chance to meet. Her father was a member of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Back then the amusement park, called Euclid Beach, only had one day a week for Black people; I think it was called Negro Day. So, CORE decided to integrate it but the cops weren’t too happy about that and they beat him up. There’s a small article, long ago, I think it was 1948 [actually 1946], with a story about Albert Luster being beaten up.

Her father was a bus driver who wanted to be a doctor. But, back then Case Western Reserve didn’t accept Black people to be doctors, so he went to an osteopath school and became an osteopath and a doctor. C. J. would always talk about her daddy watching fights on Friday night and worshiping Larry Doby, the first Black player in the American League. That was the last knowledge C. J. had of professional sports.

After going to an almost all-white high school in Cleveland, C. J. decided to go to Central State University, an all-Black publicly supported Historically Black college in Southwestern Ohio. She lasted a year, [then] met her first husband, who fathered with C. J. her two sons, Albert and Maurice. Marriage didn’t work out; he was a little too violent for C. J., and they got divorced. She moved to Washington D. C., went to the March on Washington, and interestingly, because she was raising her two sons, she did not participate in most of the upsurge of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. It totally affected her, but she wasn’t an active participant.

She came back, eventually graduated from Cleveland State University, and actually got a master’s in education with a certificate from Case Western Reserve, and started her job. But politically, her first major activity was with the Voter Service Club, where they organized and registered a lot of citizens to vote. And that’s how C. J. met much of the Black political leadership in the city of Cleveland. So, when Cleveland was found liable for intentionally segregating Cleveland students to violate the 14th Amendment, and in the future there was going to be a busing order — and to be honest, a lot of people thought that Cleveland would replicate the incredible racist violence in Boston and Louisville — C. J. organized what was called the Black Community Leaders for Peaceful School Desegregation. No, it wasn’t Black community leaders for desegregation, it was for peaceful school desegregation, because there were political divisions within some of the Black leadership on whether it was a good idea to actually desegregate the schools.

At the same time, as a 28 year old school teacher, I had put together a citywide coalition called West Siders and East Siders Let’s Come Together (WELCOME), and there was a news article when we launched it. The next day, I was going to the City Club to attend a speech by the court ordered superintendent and on the elevator I met C. J., who looked at me and said, “Weren’t you the one in the newspaper yesterday?” Here she was working for the Cuyahoga Plan, a fair housing organization, and was very immaculately dressed, and there I was in blue jeans and a white WELCOME t-shirt, with black and white hands shaking underneath the Detroit Superior Bridge. I’m sure many of you in this audience wore, or still have, either the first or the second round of Welcome Bienvenidos t-shirts.

Well, we decided we would work together to organize WELCOME and we were able to have thousands of people crossing the Detroit Superior Bridge, isolating the anti-busing racist by [illegible]. Through the course of organizing WELCOME, we fell in love and I still remember sharing our hopes and dreams for the future as we shared our love.

C. J. said she wanted to become a state senator and I said I wanted to make the revolution. Well, one out of two ain’t bad. So, as we worked with WELCOME, we decided to get married on March 13, 1981. I think there are a few people in the audience who were actually at the small ceremony. Actually, the minister who married us in our house is here today. I decided I’m not going to make references to names because I don’t want anyone to feel excluded. He said something pretty profound to us: “Your influence doesn’t come from your authority, it comes from your authenticity,” and I thought that little snippet captured who we hoped to be.

A big change came in C. J.’s life in 1984. Jesse Jackson ran for president, C. J. became an official delegate to the Democratic National Convention, [and] we camped from Cleveland to San Francisco — it took us about two or three weeks. And that was the convention where there was actually debate on the Democratic platform. A few years later — a lot of years later — when C. J. attended the 2012 convention, she said she wanted to be on the education committee. She was told, “That’s already decided. There’s no need to be on a committee.” So things had evolved a lot at that time. But that was the convention where nominee Mondale chose Geraldine Ferraro to be his vice president. Jesse Jackson commented, “We need Black women in that pipeline!”

So Shirley Chisholm, Donna Brazile, Maxine Waters, and C. J. Prentiss organized the National Political Congress of Black Women. That spurred C. J. to run for the state Board of Education, which she won decisively and took her seat in 1985. She was the only Black member, and I remember the time when this segregationist organization called Citizens Opposed to Rearranging Kids, CORK, started a school and they went to the state board to get what’s called a charter, which is like official approval. Well, C. J. spoke against it, but most of her white colleagues voted to [approve] this segregationist academy, really no different than the ones started after Brown v. Board of Education in Mississippi and across the South.

The State Board of Education produced a document on legislative recommendations, like how the legislature should spend its money on education. Since these are all pro-education people the documents were pretty good. C. J. walked into the chair of the finance committee to talk to him about these recommendations, this is in the Ohio State House, and there was a little basket there with the title DOA — Dead on Arrival. In other words, this legislature, which eventually was found guilty for violating the Ohio Constitution for equitable funding, wasn’t going to give the money that the state board wanted.

So C. J. — unbeknownst to me — decided to run for state representative. She took out all her money from her accumulated state teachers retirement fund — then unbeknownst to me — and ran against a longtime incumbent in her district. He felt challenged, so he stood in front of a shopping center saying, “Don’t vote for C. J. Prentiss, she’s married to a white man.” True, but really not a great campaign slogan. In fact, his campaign, led by the leadership of the Black political oligarchy at that time — and I don’t use that term lightly — hired 14 year olds to pass out flyers that said, “Don’t vote for C. J. Prentiss, she’s hid and kept quiet about her white husband,” or something to that effect. Well, it so happens that the only picture they could get of me was me speaking before thousands of people in a WELCOME t-shirt after a bridge walk. Now, I naively poo-pooed that and said, “I’m clearly not hidden.”

After that kind of race baiting, we organized a flyer to be passed out at a big meeting of the Democratic party saying, “Say no to race baiting.” Well, the Democratic party wouldn’t say no. But one politician did — I’m sure you’ve heard of him — Howard Metzenbaum. A true mensch when it came to fighting against racism. C. J. was incredibly hurt by how the Black political establishment turned their backs on her, including some people she was close to in the legislature, because they only wanted to defend an incumbent.

But, eventually C. J. won election to the Ohio House in 1990 and took her seat in 1991. One of her first acts was to support the mass sit-ins going on to oppose the present governor’s attempt to gut and destroy what was called general assistance. C. J. took to the House floor and eventually was successful enough to move it from 100% cut to a 50% cut. Later on, a good friend of mine, who became president of the Cincinnati Federation of Teachers, mentioned that that was the first time he had gone with a homeless advocate leader from Cincinnati to those protests, and his first remark was, “Who is that C. J. Prentiss speaking?” He was just overwhelmed with her power, her passion, and the fact that some people attribute the fact that that governor cried because he was accused of turning his back on tens of thousands of poor people.

She also entered the Ohio House with a whole plan to transform K–3 education, called the Third Grade Guarantee. Some of you remember it, great. It was comprehensive all day kindergarten, reduced class sizes, community parent centers, plans to retrain teachers to be able to teach in small classes, and it was introduced. But, of course, a legislature that was found liable for unconstitutional funding wasn’t willing to put up the money, so she began a statewide petition campaign to place it on the ballot. She traveled all around the state. Later on she traveled all around the country, but not this time.

What she found out is the way this program was set up for at-risk school districts, in other words places with low graduation rates, and some of the districts that qualified were in southern Ohio, in the Appalachia area. So she spoke at school boards, she spoke in front of a lot of organizations. However, the petition campaign was derailed because of the election of 1994. That was when one of C. J.’s campaign workers forgot to fill in the form correctly for her petitions and C. J. signed it instead. That was technically illegal, so C. J. was thrown off the ballot for the Democratic primary, but ran as an independent.

I remember that AFSCME, the labor union, commissioned a poll about who knew C. J. and it came back that 25% of her constituents knew who C. J. was. C. J.’s response was, “That’s all?” And the people who did the polling said, “That’s one of the highest we ever got.” So, she ran as an independent. However, the Democratic candidate was pretty aggravated by C. J.’s attacks. He was quoted in the paper saying, “C. J. Prentiss is a clinker top, Aunt Jemima, Afro-wearing candidate, married to a hippie-looking Jew, and a poor one at that.” Still to this day I don’t know if he was referring to our economic status or my lack of religiosity.

But C. J. won overwhelmingly, and, interestingly, I think she was one of the only independents ever to win. And, all the people who opposed her in 1986 came to her defense and denounced sexism and antisemitism. Interesting how things come around. But, I still remember that election night. We were celebrating C. J.’s victory and we received a call from a fellow lawmaker, in fact her former roommate in Columbus. The first comments were, “We lost the House.” This was a turning point for C. J.’s role and the Democratic party’s role in the Ohio House. It didn’t stop C. J. from agitating and organizing.

When she went to the 1992 inauguration for Bill Clinton, she attended some activity beforehand and she wanted to run to the bathroom before the Ohio State band would play. Well, she never got back to that band performance because she had to wait so long to go to the bathroom. So she decided she was going to produce a law that required an equal number of bathrooms in all new construction. It was called potty parity, and I was overwhelmed by the level of enthusiastic support, because this affected people’s day-to-day life. We would be stopped at traffic lights and women would give the thumbs up. She appeared on radio in Australia and New York. The University of Michigan did a study of how long men went to the bathroom and how long women did. And of course the plumbers were enthusiastic supporters. It passed! It also paved the way for one of the most productive relationships in her life.

She was hiring a new legislative assistant and the assignment was to write a press release about party parity, and the person who did the best job would be speaking to you in a few minutes, George Boas, a true, loyal, thoughtful, intelligent, and guiding light for C. J. for the rest of her legislative career. By the time C. J. was already in the legislature, we would like to go camping in the summer. I had time off from teaching and she had time off. But she was always very worried that she would have to come back and campaign. Elections for every two years. So finally I said to her, “C. J., last time you got 82% of the vote. Can’t we go?” She called up her Republican opponent, they talked, and then C. J. said, “Well, we’ll see who ends up in Columbus.” Her opponent said, “Columbus? What’s in Columbus?” The person didn’t even know that, if elected, she would serve in Columbus. That’s how deep the opposition was.

I still remember in 1996, C. J. was active in the reelection of Clinton. There’s a history in Cleveland that people who campaign outside elections, on the day of election or for early voting, would receive money from the party. I remember walking into our house, going into our bedroom, and there on the bed was $10,000 in $10s, all ready to pass out to the people who are going to be poll workers that day. Perfectly legal, but a little jaw-dropping for me to see that much cash.

One more story. In the beginning of C. J.’s career, there was a breakfast program for children. Cleveland had paid for it but the districts in Appalachia couldn’t afford it. Republicans in the Senate, even though she was in the Senate, stopped the funding. So C. J. decided to oppose that by going on a hunger strike. She organized thirty people across the state to join her. I think it lasted five or ten days. And they won; the Republicans put back the money. Which I think tells the story that C. J.’s commitment wasn’t only to racial equality or feminism, it was also a commitment for all marginalized people, particularly poor white people. She was willing to go on a hunger strike for the white kids in Appalachia.

In 1998, C. J. had an opening and was able to be elected to the state senate. There, she became not only the president of the Ohio Legislative Black Caucus. A few years earlier, the corporate class in Cleveland decided they wanted to get rid of an elected school board, so they put forward in the legislature a plan for what was called Mayor Control. The Cleveland Teachers Union opposed that strenuously, as did almost all the lawmakers in this area.

The Cleveland Plain Dealer, which was then a newspaper, put all these lawmakers on the front page as the enemy of the children, with their pictures. He even wrote a special editorial aimed at C. J. and me. A few months before, I had been chosen as the National AFT Teacher of the Year and the Plain Dealer wrote a glowing editorial about my insight, my leadership, actually my personality and my beard. And then they wrote an editorial that said, “C. J. Prentiss is controlled by Cleveland Teachers Union leader Michael Charney about Mayor Control.” Anyone who knows C. J. knows that I did not control C. J., not at all. But they wrote the editorial, and I ran into the person who wrote it a few months later. I asked her why she wrote it and she said, “My editor made me do it.” That editor now writes a weekly column for Cleveland.com and he’s really changed stripes; he exposes the massive corruption every day in the Ohio legislature. But back then, The Plain Dealer was really carrying the water for a certain kind of corporate control.

At the same time, another editor attacked C. J. for being too Black. And she was the head of the Ohio Legislative Black Caucus! How could you be too Black and be in charge of Black politics?

C. J. heavily advocated for reduced class size. She brought in the author and designer of what was called the Tennessee Star Study. We’re all familiar with that. It followed students who were in 15-to-1 classes in Tennessee and showed profound effects not only on the achievement then, but ten years later, and actually now we are less likely to end up in trouble. So she brought in the author of that study to meet with Republican leadership, and as they were leaving that meeting a group from the Buckeye Institute passed out something that says, “Class size isn’t worth it.” C. J. came home and said, “We need a left-wing think tank in Cleveland.” And we, along with the head of the AFL-CIO and the present director of a tax group in Washington, formed Policy Matters Ohio.

Policy Matters Ohio was looking for funding so I went to the Gund Foundation and asked for $30,000. The director said, “No, we’re not going to give you $30,000, we’re going to give you $50,000 to begin with.” Since that time some of my best friends are leaders of Policy Matters Ohio and do research. C. J. and I were founders of Policy Matters Ohio.

A few years later, at a national gathering of like-minded groups set up by the Economic Policy Institute gathering in Cleveland, C. J. was asked to give a keynote speech. She looked at the crowd and began with, “Where are all the Black people?” Because it was mostly white people. And to some extent that spurred on a different form of hiring and research by some of these groups. C. J. always found it incredibly frustrating to go speak before progressive groups and almost everyone was white.

C. J. continued her legislative work, actually being one of the highest elected officials in 2004 for the favorite son candidate of Dennis Kucinich. We went to the Boston Convention and I remember hearing a keynote from this state senator from Illinois. After he spoke, C. J. and I looked at each other and said, “He’s going to be president of the United States someday.” We were really reinforced when, after that time in Boston, we walked through what was called Little Italy and there were these white Italian people on their porches wearing Obama buttons. So you could see that that was the beginning of something.

C. J. was elected minority leader in 2005 of the Ohio Senate. Someone not really adept at politics said, “What’s the minority leader? Are you in charge of the Black ones?” “No.” C. J. was a real militant minority: Black, a woman, a Democrat, and a progressive. Sometimes she got a chance to be by herself in that kind of minority. But she created a legislative agenda, one of which was to raise the Ohio minimum wage. And a year before we knew she was going to be minority leader, C. J. and I and George Boas crafted a whole two and a half year plan. We introduced it into the Ohio Senate. Ohio Policy Matters would do the research to show the tens of thousands of people would benefit. We would hold a hearing. What we didn’t expect was that all the Republicans would walk out of that hearing, and then we’d bring it to the ballot and form a coalition of community organizations, religious organizations, elected officials, labor. C. J. successfully pulled together those people, landed on $6.85, and C. J. traveled around the state speaking for it.

I organized high school students across the state to actually gather signatures, which eventually became the Ohio Youth Agenda. We won, and I remember on election night, C. J. got a call from U.S. Senator Sherrod Brown, his first call for that day, congratulating C. J. on her leadership. C. J. was quite moved.

Well, in Ohio they have term limits, so C. J. left the legislature in 2006 and started the C. J. Prentiss Emerging Leaders Network, which was for people already in leadership but not fully, totally in charge. C. J. was very proud that some of the people who were involved with that were state senators. And two of the people, Lauren Groh-Wargo and Nsé Ufot, basically started the political movement in Georgia to turn Georgia from red to purple to blue. Those were C. J. Prentiss Emerging Leaders.

After C. J. retired, she was an early supporter of Ted Strickland. So, Ted Strickland asked her, “What do you want to do?” C. J. says, “I want to organize in low-income high schools to increase the graduation rate of African American males.” They had like $70-$80,000 in the budget and started across Ohio, planning many, many, many high schools a way of providing back up to kids in ninth grade who might not succeed. It was very successful.

We have some people in the audience who were the staffers to C. J. to raise the graduation of African American males. C. J. retired after working in the state, in the Ohio Department of Education, a place she found riddled with bureaucracy. In our spare time not only did we go camping, but we attended Bruce Springsteen concerts. I remember in 2012, at Obama’s reelection, in downtown Cleveland we sat as close as that first row next to Bruce Springsteen as he sang in support of Obama’s candidacy. It was quite moving, actually.

C. J., at about that time, surprised me at home and said, “I bought a cottage on the lake. You can’t come and see it for at least six months.” And C. J. spent the rest of her life rehabilitating and adding to what someone once called our compound on Lake Erie, and she loved it. Oh, did she love it. She would watch the HGTV Channel and say, “Michael, go in the other room and watch a Cavs game.” That was really her pride and joy.

But there was something else in the last ten years of her life that really became important: She joined the Hiawatha Church of God In Christ in Ashtabula. She did it for two major reasons. She wanted to be close to a Black community, and she wanted to achieve salvation by her belief in Jesus Christ. Two things that I couldn’t really be a part of. But, she would go every Sunday and pick up someone she called Mother Miller at 8:30 in the morning. Then she got so into it she would be tutoring the Bible on Monday and watching Zoom church services on Wednesday. And I want to make a special acknowledgement to the congregants of Hiawatha who have been and are so incredibly supportive. She loved all of you.

Her last real political entree was to become an elected delegate for Bernie Sanders. She was an enthusiastic supporter, especially because the Clintons had supported ending welfare as you know it. And C. J. knew the number of people in her district who were crushed deeper by that. We went to the convention and went to all the side meetings, and heard some of the future leaders of the United States. Then, after that, she wouldn’t even accept invitations to speak, except at her church. I could tell she was in trouble when she would travel to all these high schools and she would come back to our house and I said, “How was it?” and she would just comment on how many stairs there were to go up. So, I’m going to come back and read a few things later but right now I’d like to introduce George Boas to give a perspective on her legislative career.

[George Boas speaks, then Michael Charney returns]

I’m back. When you finish your talk you think what did you forget, so I want to add a few things. When C. J. was in the senate, the governor had all these task forces: Student Success, Funding Success, Teacher Success. C. J. propelled the one on teacher success when she visited me at Central Middle School and found out that only one teacher was certified to teach science. She thought that was outrageous, so she pushed the governor to set up the task force on teacher success. And she had a strategy; these task forces needed to include C. J.

Let’s play some of her favorite songs. Now we have two of our good friends, Merle Johnson and Diana Porter, to come up and sing “This Little Light of Mine.” Diana and I and C. J. go back almost as far as C. J. and I and Merle. We met when C. J. helped found the National Coalition of Education Activists, a national coalition of parents, teachers, [and] union leaders to fight from the bottom up for school change. Diana is a founding member of what is called MUSE, which is a feminist choir in Cincinnati. C. J. loved this song “This Little Light of Mine,” and even when she went to different high schools, she would get the principal and all her team to end their meeting with “This Little Light of Mine.”

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn