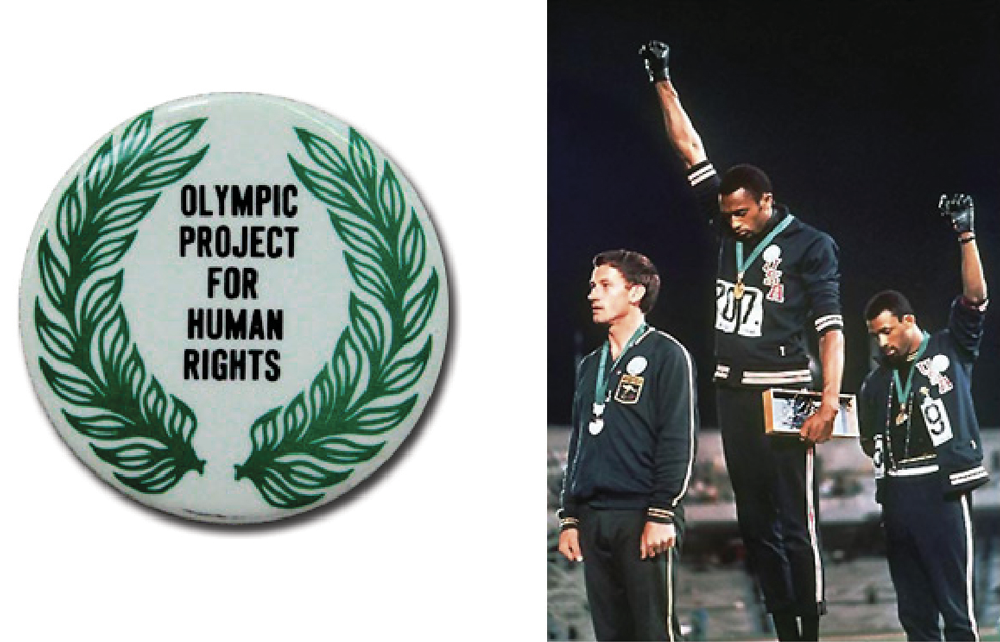

LEFT: The Olympic Project for Human Rights badge, worn by activist athletes in the 1968 Olympic Games, originally called for a boycott of the 1968 Olympic Games. RIGHT: This iconic photo appears in many U.S. history textbooks, stripped of the story of the planned boycott and demands, creating the appearance of a solitary act of defiance.

By Dave Zirin

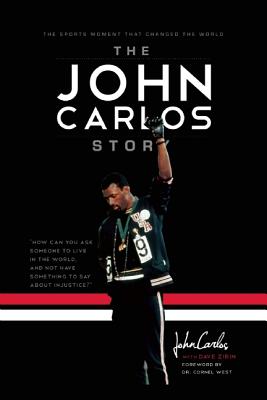

It has been almost 44 years since Tommie Smith and John Carlos took the medal stand following the 200-meter dash at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City and created what must be considered the most enduring, riveting image in the history of either sports or protest. But while the image has stood the test of time, the struggle that led to that moment has been cast aside.

When mentioned at all in U.S. history textbooks, the famous photo appears with almost no context. For example, Pearson/Prentice Hall’s United States History places the photo opposite a short three-paragraph section, “Young Leaders Call for Black Power.” The photo’s caption says simply that “. . . U.S. athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised gloved fists in protest against discrimination.”

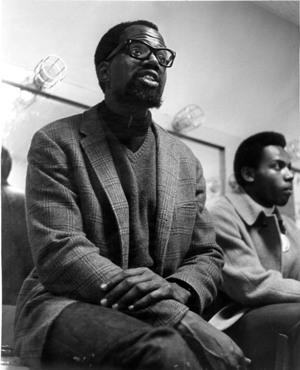

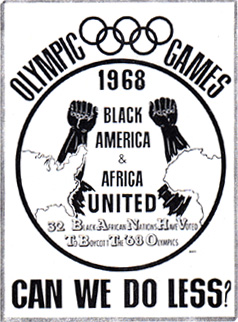

The media — and school curricula — fail to address the context that produced Smith and Carlos’ famous gesture of resistance: It was the product of what was called “The Revolt of the Black Athlete.” Amateur Black athletes formed OPHR, the Olympic Project for Human Rights, to organize an African American boycott of the 1968 Olympic Games. OPHR, its lead organizer, Dr. Harry Edwards, and its primary athletic spokespeople, Smith and the 400-meter sprinter Lee Evans, were deeply influenced by the Black freedom struggle. Their goal was nothing less than to expose how the United States used Black athletes to project a lie about race relations both at home and internationally.

OPHR had four central demands: restore Muhammad Ali’s heavyweight boxing title, remove Avery Brundage as head of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), hire more African American coaches, and disinvite South Africa and Rhodesia from the Olympics. Ali’s belt had been taken by boxing’s powers that be earlier in the year for his resistance to the Vietnam draft. By standing with Ali, OPHR was expressing its opposition to the war. By calling for the hiring of more African American coaches as well as the ouster of Brundage, they were dragging out of the shadows a part of Olympic history those in power wanted to bury. Brundage was an anti-Semite and a white supremacist, best remembered today for sealing the deal on Hitler’s hosting the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. By demanding the exclusion of South Africa and Rhodesia, they aimed to convey their internationalism and solidarity with the Black freedom struggles against apartheid in Africa.

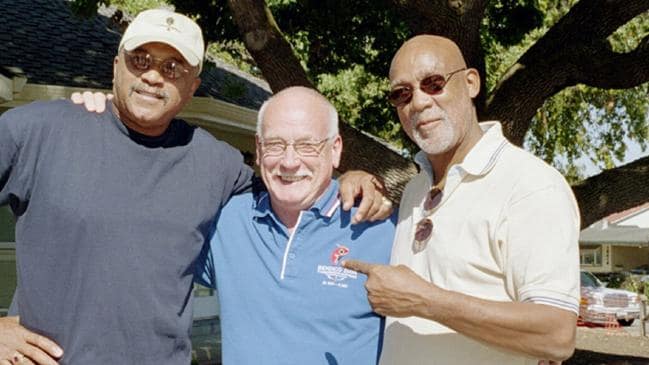

Dr. Harry Edwards led the Olympic Project for Human Rights, calling for the boycott of the 1968 Olympics.

The wind went out of the sails of a broader boycott for many reasons, partly because the IOC re-committed to banning apartheid countries from the Games. The more pressing reason the boycott failed was that athletes who had spent their whole lives preparing for their Olympic moment simply couldn’t bring themselves to give it up.

There also emerged accusations of a campaign of harassment and intimidation orchestrated by people supportive of Brundage. Despite all of these pressures, a handful of Olympians was still determined to make a stand. In communities across the globe, they were hardly alone.

The lead-up to the Olympics in Mexico City was electric with struggle. Already in 1968, the world had seen the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, demonstrating that the United States was nowhere near “winning the war”; the Prague Spring, during which Czech students challenged tanks from the Stalinist Soviet Union, demonstrating that dissent was crackling on both sides of the Iron Curtain; and the April 4 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the urban uprisings that followed — along with the exponential growth of the Black Panther Party in the United States — that revealed an African American freedom struggle unassuaged by the civil rights reforms that had transformed the Jim Crow South. Then, on October 2, 10 days before the opening ceremonies of the 1968 Olympic Games, Mexican security forces massacred hundreds of students and workers in Mexico City’s Tlatelolco Square.

Although the harassment and intimidation of the OPHR athletes cannot be compared to this slaughter, the intention was the same — to stifle protest and make sure that the Olympics were “suitable” for visiting dignitaries, heads of state, and an international audience. It was not successful.

On the second day of the Games, Smith and Carlos took their stand. Smith set a world record, winning the 200-meter gold, and Carlos captured the bronze. Smith then took out the black gloves. The silver medalist, a runner from Australia named Peter Norman, attached an Olympic Project for Human Rights patch onto his chest to show his solidarity on the medal stand.

As the stars and stripes ran up the flagpole and the national anthem played, Smith and Carlos bowed their heads and raised their fists in what was described across the globe as a “Black Power salute,” creating a moment that would define the rest of their lives. But there was far more to their actions on the medal stand than just the gloves. The two men wore no shoes, to protest Black poverty as well as beads and scarves to protest lynching.

As the stars and stripes ran up the flagpole and the national anthem played, Smith and Carlos bowed their heads and raised their fists in what was described across the globe as a “Black Power salute,” creating a moment that would define the rest of their lives. But there was far more to their actions on the medal stand than just the gloves. The two men wore no shoes, to protest Black poverty as well as beads and scarves to protest lynching.

Within hours, the IOC planted a rumor that Smith and Carlos had been stripped of their medals (although this was not in fact true) and expelled from the Olympic Village. Brundage wanted to send a message to every athlete that there would be punishment for any political demonstrations on the field of play.

But Brundage was not alone in his furious reaction. The Los Angeles Times accused Smith and Carlos of a “Nazi-like salute.” Time had a distorted version of the Olympic logo on its cover but instead of the motto “Faster, Higher, Stronger,” it blared “Angrier, Nastier, Uglier.” The Chicago Tribune called the act “an embarrassment visited upon the country,” an “act contemptuous of the United States,” and “an insult to their countrymen.” Smith and Carlos were “renegades” who would come home to be “greeted as heroes by fellow extremists,” lamented the paper.

But the coup de grâce was by a young reporter for the Chicago American named Brent Musburger who called them “a pair of black-skinned storm troopers.”

But if Smith and Carlos were attacked from a multitude of directions, they also received many expressions of support, including from some unlikely sources. For example, the U.S. Olympic crew team, all white and entirely from Harvard, issued the following statement:

“We — as individuals — have been concerned about the place of the black man in American society in their struggle for equal rights. As members of the U.S. Olympic team, each of us has come to feel a moral commitment to support our black teammates in their efforts to dramatize the injustices and inequities which permeate our society.”

In 2008, Tommie Smith and John Carlos were given the Authur Ashe Award for possessing strength in the face of adversity, courage in the face of peril and the willingness to stand up for their beliefs no matter what the cost. From espn.go.com/espys/arthurasheaward.

Smith and Carlos sacrificed privilege and glory, fame and fortune, for a larger cause — civil rights. As Carlos says, “A lot of the [Black] athletes thought that winning [Olympic] medals would supersede or protect them from racism. But even if you won a medal, it ain’t going to save your momma. It ain’t going to save your sister or children. It might give you 15 minutes of fame, but what about the rest of your life?”

The story of Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Olympics deserves more than a visual sound bite in a quickie textbook section on “Black Power.” As the Zinn Education Project points out in its “If We Knew Our History” series, this is one of many examples of the missing and distorted history in school, which turns the curriculum into a checklist of famous names and dates. When we introduce students to the story of Smith and Carlos’ defiant gesture, we can offer a rich context of activism, courage, and solidarity that breathes life into the study of history — and the long struggle for racial equality.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

Posted on: GOOD | The Nation.

© 2012 The Zinn Education Project, a project of Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn