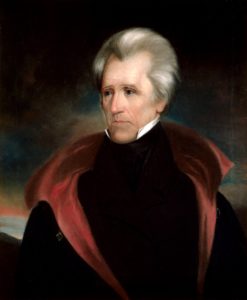

Andrew Jackson.

“One of the greatest victories for the people of America since Andrew Jackson,” Rudy Giuliani, former mayor of New York City, said of Donald Trump’s success in the 2016 election. We agree that Trump and Jackson have a lot in common, but neither election can be accurately described as a victory for anyone other than the wealthy elite.

Textbooks often portray Jackson as a “man of the people.” However, as Howard Zinn describes in this excerpt from A People’s History of the United States,

Jackson was a land speculator, merchant, slave trader, and the most aggressive enemy of the Indians in early American history.

The reading below is followed by links to lessons and other resources on the Zinn Education Project website that can be used to introduce students to Andrew Jackson, including “The Cherokee/Seminole Removal Role Play” and “Andrew Jackson and the ‘Children of the Forest’.”

By Howard Zinn

[Andrew Jackson] became a hero of the War of 1812, which was not (as usually depicted in American textbooks) just a war against England for survival, but a war for the expansion of the new nation, into Florida, into Canada, into Indian territory.Not all of Jackson’s enlisted men were enthusiastic for the fighting. There were mutinies; the men were hungry, their enlistment terms were up, they were tired of fighting and wanted to go home. Jackson wrote to his wife about “the once brave and patriotic volunteers. . . sunk. . . to mere whining, complaining, seditioners, and mutineers. . . .” When a 17-year-old soldier who had refused to clean up his food, and threatened his officer with a gun, was sentenced to death by a court-martial, Jackson turned down a plea for commutation of sentence and ordered the execution to proceed. He then walked out of earshot of the firing squad.

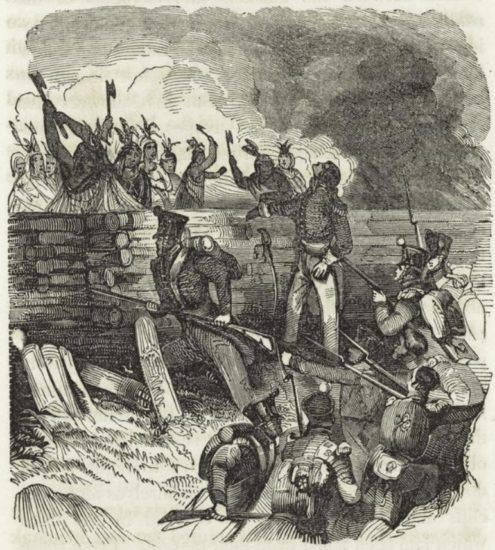

Battle of Horseshoe Bend (Tohopeka), Creek War. Image: New York Public Library.

Jackson became a national hero when in 1814 he fought the Battle of Horseshoe Bend against a thousand Creeks and killed 800 of them, with few casualties on his side. His white troops had failed in a frontal attack on the Creeks, but the Cherokees with him, promised governmental friendship if they joined the war, swam the river, came up behind the Creeks, and won the battle for Jackson.

When the war ended, Jackson and friends of his began buying up the seized Creek lands. He got himself appointed treaty commissioner and dictated a treaty which took away half the land of the Creek nation. Rogin says it was “the largest single Indian cession of southern American land.” It took land from Creeks who had fought with Jackson as well as those who had fought against him, and when Big Warrior, a chief of the friendly Creeks, protested, Jackson said:

Listen . . . The United States would have been justified by the Great Spirit, had they taken all the land of the nation . . . . Listen, the truth is, the great body of the Creek chiefs and warriors did not respect the power of the United States. They thought we were an insignificant nation, that we would be overpowered by the British . . . they were fat with eating beef, they wanted flogging . . . We bleed our enemies in such cases to give them their sense.

As Michael Rogin puts it: “Jackson had conquered ‘the cream of the Creek country,’ and it would guarantee southwestern prosperity. He had supplied the expanding cotton kingdom with a vast and valuable acreage.”

From 1814 to 1824, in a series of treaties with the southern Indians, whites took over three-fourths of Alabama and Florida, one-third of Tennessee, one-fifth of Georgia and Mississippi, and parts of Kentucky and North Carolina. Jackson played a key role in those treaties, and according to Rogin, “His friends and relatives received many of the patronage appointments—as Indian agents, traders, treaty commissioners, surveyors and land agents. . . . “

Jackson himself described how the treaties were obtained: “ . . . we addressed ourselves feelingly to the predominant and governing passion of all Indian tribes, i.e., their avarice or fear.” He encouraged white squatters to move into Indian lands, then told the Indians the government could not remove the whites and so they had better cede the lands or be wiped out. He also, Rogin says, “practiced extensive bribery.”

These treaties, these land grabs, laid the basis for the cotton kingdom, the slave plantations. Every time a treaty was signed, pushing the Creeks from one area to the next, promising them security there, whites would move into the new area and the Creeks would feel compelled to sign another treaty, giving up more land in return for security elsewhere.

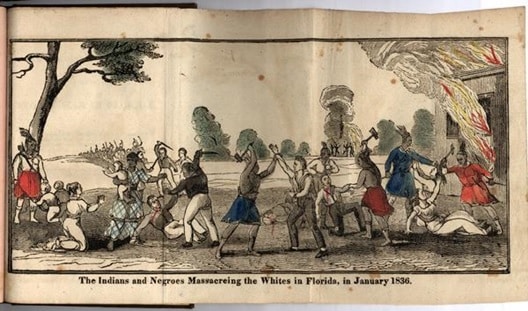

Jackson’s work had brought the white settlements to the border of Florida, owned by Spain. Here were the villages of the Seminole agents in their resistance to the Americans. Settlers moved into Indian lands. Indians attacked. Atrocities took place on both sides. When certain village refused to surrender people accused of murdering whites, Jackson ordered the villages destroyed.

Another Seminole provocation: escaped black slaves took refuge in Seminole villages. Some Seminoles bought or captured black slaves, but their form of slavery was more like African slavery than cotton plantation slavery. The slaves often lived in their own villages, their children often became free, there was much intermarriage between Indians and blacks, and soon there were mixed Indian-black villages—all of which aroused Southern slaveowners who saw this as a lure to their own slaves seeking freedom.

Jackson began raids into Florida, arguing it was a sanctuary for escaped slaves and for marauding Indians. Florida, he said, was essential to the defense of the United States. It was that classic modern preface to a war of conquest. Thus began the Seminole War of 1818, leading to the American acquisition of Florida. It appears on classroom maps politely as “Florida Purchase, 1819”—but it came from Andrew Jackson’s military campaign across the Florida border, burning Seminole villages, seizing Spanish forts, until Spain was “persuaded” to sell. He acted, he said, by the “immutable laws of self-defense.”

Jackson began raids into Florida, arguing it was a sanctuary for escaped slaves and for marauding Indians. Florida, he said, was essential to the defense of the United States. It was that classic modern preface to a war of conquest. Thus began the Seminole War of 1818, leading to the American acquisition of Florida. It appears on classroom maps politely as “Florida Purchase, 1819”—but it came from Andrew Jackson’s military campaign across the Florida border, burning Seminole villages, seizing Spanish forts, until Spain was “persuaded” to sell. He acted, he said, by the “immutable laws of self-defense.”

Jackson then became governor of the Florida Territory. He was able now to give good business advice to friends and relatives. To a nephew, he suggested holding on to property in Pensacola. To a friend, a surgeon-general in the army, he suggested buying as many slaves as possible, because the price would soon rise.

Leaving his military post, he also gave advice to officers on how to deal with the high rate of desertion. (Poor whites—even if willing to give their lives at first—may have discovered the rewards of battle going to the rich.) Jackson suggested whipping for the first two attempts, and the third time, execution.

The leading books on the Jacksonian period, written by respected historians (The Age of Jackson by Arthur Schlesinger; The Jacksonian Persuasion by Marvin Meyers), do not mention Jackson’s Indian policy, but there is much talk in them of tariffs, banking, political parties, political rhetoric. If you look through high school textbooks and elementary school textbooks in American history you will find Jackson the frontiersman, soldier, democrat, man of the people—not Jackson the slaveholder, land speculator, execution of dissident soldiers, exterminator of Indians.

This is not simply hindsight (the word used for thinking back differently on the past). After Jackson was elected President in 1828 (following John Quincy Adams, who had followed Monroe, who had followed Madison, who had followed Jefferson), the Indian Removal bill came before Congress and was called, at the time, “the leading measure” of the Jackson administration and “the greatest question that ever came before Congress” except for matters of peace and war. By this time the two political parties were the Democrats and Whigs, who disagreed on banks and tariffs, but not on issues crucial for the white poor, the blacks, the Indians—although some white working people saw Jackson as their hero, because he opposed the rich man’s bank.

Under Jackson, and the man he chose to succeed him, Martin Van Buren, 70,000 Indians east of the Mississippi were forced westward. In the North, there weren’t that many, and the Iroquois confederation in New York stayed. But the Sac and Fox Indians of Illinois were removed, after the Black Hawk War (in which Abraham Lincoln was an officer, though he was not in combat).

Forced Move by Max Standley courtesy R. Michelson Galleries (www.RMichelson.com).

. . .

As soon as Jackson was elected President, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi began to pass laws to extend the states’ rule over the Indians in their territory. These laws did away with the tribe as a legal unit, outlawed tribal meetings, took away the chiefs’ powers, made the Indians subject to militia duty and state taxes, but denied them the right to vote, to bring suits, or to testify in court. Indian territory was divided up, to be distributed by state lottery. Whites were encouraged to settle on Indian land.

However, federal treaties and federal laws gave Congress, not the states, authority over the tribes. The Indian Trade and Intercourse Act, passed by Congress in 1802, said there could be no land cessions except by treaty with a tribe, and said federal law would operate in Indian territory. Jackson ignored this, and supported state action.

It was a neat illustration of the uses of the federal system: depending on the situation, blame could be put on the states, or on something even more elusive, the mysterious Law before which all men, sympathetic as they were to the Indian, must bow. As Secretary of War John Eaton explained to the Creeks of Alabama (Alabama itself was an Indian name, meaning “Here we may rest”): “It is not your Great Father who does this; but the laws of the Country, which he and every one of his people is bound to regard.”

The proper tactic had now been found. The Indians would not be “forced” to go West. But if they chose to stay they would have to abide by state laws, which destroyed their tribal and personal rights and made them subject to endless harassment and invasion by white settlers coveting their land. If they left, however, the federal government would give them financial support and promise them lands beyond the Mississippi.

. . .

As Jackson took office in 1829, gold was discovered in Cherokee territory in Georgia. Thousands of whites invaded, destroyed Indian property, staked out claims. Jackson ordered federal troops to remove them, but also ordered Indians as well as whites to stop mining. Then he removed the troops, the whites returned, and Jackson said he could not interfere with Georgia’s authority.

The white invaders seized land and stock, forced Indians to sign leases, beat up Indians who protested, sold alcohol to weaken resistance, killed game which Indians needed for food. But to put all the blame on white mobs, Rogin says, would be to ignore “the essential roles played by planter interests and government policy decisions.” Food shortages, whiskey, and military attacks began a process of tribal disintegration. Violence by Indians upon other Indians increased.

Treaties made under pressure and by deception broke up Creek, Choctaw, and Chickasaw tribal lands into individual holdings, making each person a prey to contractors, speculators, and politicians. The Chickasaws sold their land individually at good prices and went west without much suffering. The Creeks and Choctaws remained on their individual plots, but great numbers of them were defrauded by land companies. According to one Georgia bank president, a stockholder in a land company, “Stealing is the order of the day.”

. . . .

According to Van Every, just before Jackson became president, in the 1820s, after the tumult of the War of 1812 and the Creek War, the Southern Indians and the whites had settled down, often very close to one another, and were living in peace in a natural environment which seemed to have enough for all of them. They began to see common problems. Friendships developed. White men were allowed to visit the Indian communities and Indians often were guests in white homes.

The forces that led to removal did not come, Van Every insists, from the poor white frontiersmen who were neighbors of the Indians. They came from industrialization and commerce, the growth of populations, of railroads and cities, the rise in value of land, and the greed of businessmen. “Party managers and land speculators manipulated the growing excitement. . . . Press and pulpit whipped up the frenzy.” Out of that frenzy the Indians were to end up dead or exiled, the land speculators richer, the politicians more powerful. As for the poor white frontiersman, he played the part of a pawn, pushed into the first violent encounters, but soon dispensable.

Read more in A People’s History of the United States.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn