Scholar and activist Garrett Felber, along with incarcerated prison abolitionists Michael “Safear” Ness and Stevie Wilson, joined the Zinn Education Project online on April 26, 2021 for a conversation about the growth of the prison industrial complex and resistance movements. Educator and teacher organizer Jesse Hagopian, editor of Teaching for Black Lives and Zinn Education Project staff member, facilitated the conversation. Wilson and Safear responded to questions via pre-recorded interviews. Audio clips and transcripts offered below.

This online history class is part of the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle campaign.

Participant Reflections

Here are a few reactions from participants. There are many more below.

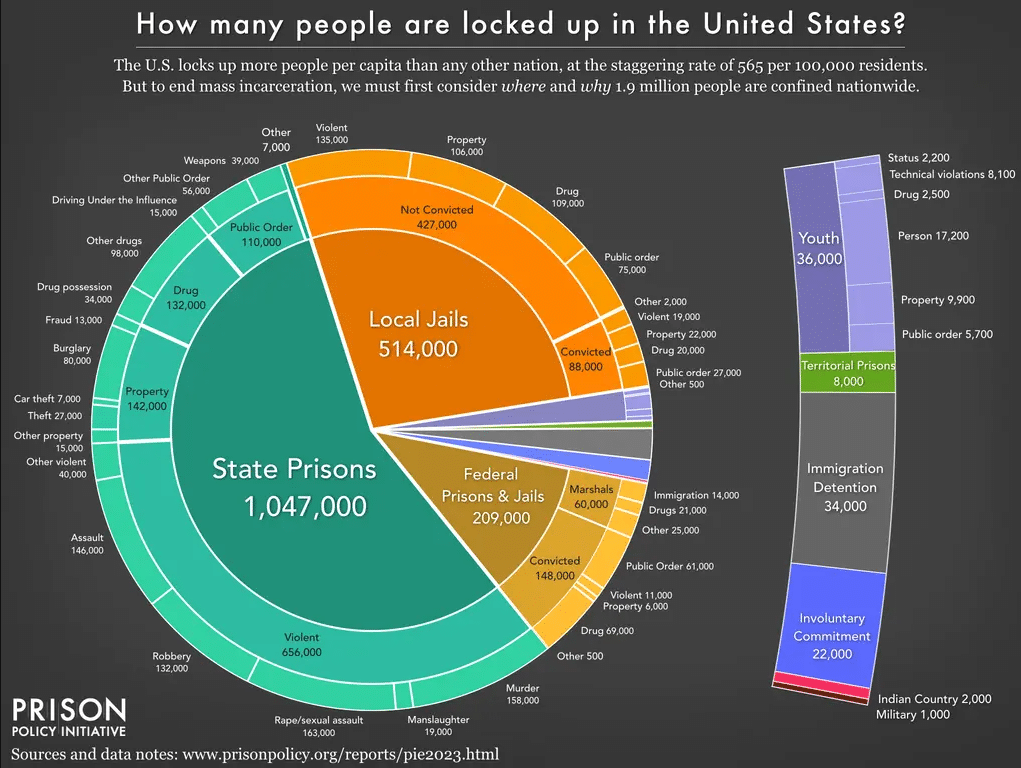

Over 2 million people are incarcerated in the United States, yet within school students minimally learn about the prison system and the life of an incarcerated person.

As a teacher educator, I want to consider ways to support my future teachers in thinking about how many students/children may be impacted by a loved one who is incarcerated.

Thank you — I was exhausted after a long day and almost didn’t make it in time. I am so glad I did — I am leaving with more energy and enthusiasm than I started with. That is always a good sign of a great learning opportunity. Thank you!

It was so impactful and I truly felt privileged to hear from folks who are imprisoned. I didn’t expect this from the session but I should have known that ZEP would not and could not discuss such a topic without giving voice to those most directly impacted by the prison industrial complex! I relished learning about a topic that’s rarely discussed or taught. Thank you!

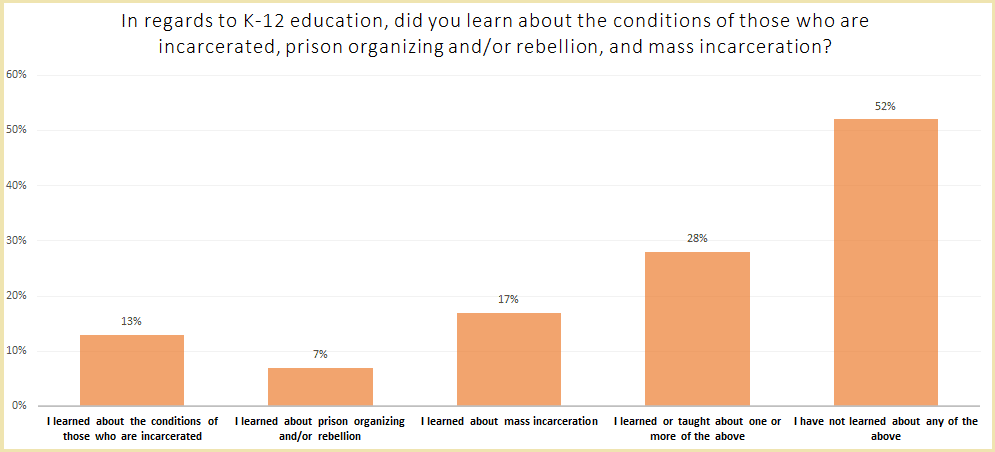

During the session we posted a poll on what people learned about incarceration. More than half of attendees had no education on the topic in K-12.

Find highlights of the session, interview transcript, a video recording of the class (except breakout room segment), recommended resources, and more participant feedback.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: We’re lucky to be joined in person by Dr. Garrett Felber, author of Those Who Know Don’t Say: The Nation of Islam, the Black Freedom Movement and the Carceral State, and our special guests, we will have audio clips from prison abolitionist Safear Ness and also prison abolitionist Stevie Wilson, both of whom are currently incarcerated. Also we hope that after the break we can be joined live on the phone from the prison by Stevie Wilson. So, Dr. Garrett Felber, welcome, thanks for joining us.

Garrett Felber: I appreciate it so much. I’m so honored to be with you all tonight, so thanks for the invite.

Hagopian: Excellent. It is so great that you’re joining us teachers, because for each one of these teachers that you speak to this evening, you’re going to be reaching like 150 other students, and we are going to spread this message about the struggle to undo the prison industrial complex. I really was fascinated by your book. I realized that I myself had some master narratives about the Nation of Islam [NOI] in my head that I hadn’t undone yet. So I learned quite a bit. I think it really deepened my understanding of the Black Freedom Struggle in general, and specifically the NOI. So, thank you for that.

You write in the book, [that] “Muslim activism has largely been erased in historical accounts of Black Power, absent from the major uprisings in Harlem in 1964, Watts in 1965, and Attica in 1971 that defined the era.” So what happens to our understanding of those uprisings and of the Nation of Islam — and the Black Freedom Struggle more generally — when we understand the role that the NOI played in them?

Felber: Thanks for the question. And again, just thank you everyone — to the organizers and all the educators and folks here in the audience tonight. I should say, when I wrote this book, it’s not an organizational history of the Nation of Islam. I was concerned largely with this question that you posed, which is what happens when we put the NOI at the center of the mid-century Black Freedom Struggle.

And I think it does a couple of things that are helpful, not just historically, but also for our movements today. One of them is just thinking about the central role of Black nationalism during that movement. Oftentimes, when we talk about Black nationalism, or we teach it, there’s this sort of golden age of Black nationalism with the UNIA and the Garvey movement. Then it’s seen as sort of in recession during the heart of what we might see as the classical Civil Rights Movement of the ‘50s and ‘60s. Then there’s this blossoming, right of SNCC and the Black Panthers and the late-60s moment. And I think the Nation of Islam helps bridge that.

There’s a point, really, where [for] my students, it starts to click for them, because they often say, “Well, Malcolm X was with the Black Power movement, right? But Malcolm is assassinated before the phrase Black Power is ever shouted amongst a mainstream movement. So how do we make sense of that?” In part, we make sense of it because the Nation during the ‘50s and ‘60s is really carrying that torch of Black nationalism forward, during the heart of a movement that we often don’t associate with Black nationalism. And I think that’s important, in part because it offers a sort of dissonance in that movement. If we think about the Civil Rights Movement as really the struggle between desegregation and segregation, the Nation of Islam is talking about racial separation. And Malcolm’s talking about racial separation as distinct from segregation in the sense that it’s something between two evils rather than segregation, which is imposed by oppressor upon oppressed. And the reason I think that’s useful for us in thinking about social movements more generally is that these are not ideologically coherent, consistent struggles. There’s all sorts of arguments about what we’re fighting for, what strategies to use, so I think that’s really valuable because often people talk about, in contemporary movements, when there’s dissonance, everyone’s sort of worried about unity. Is this falling apart? And I think it’s just a good reminder to understand that there’s always a really healthy argument happening within social movements over strategies and goals.

Then I think, lastly and perhaps most importantly for me, that when you center the Nation of Islam within the mid-century Black Freedom Struggle, you’re necessarily centering some of the most criminalized folks. The Nation was organizing people who were currently and formerly incarcerated. The Nation was surveilled and policed and brutalized during the ‘50s and ‘60s, as I documented in the book, as much as or perhaps more than other folks within Black communities. And they were responding to that and organizing around things like solitary confinement and police murders. What that does then is it sort of shifts our focus to not seeing the prisoners’ rights movement — and even contemporary abolition — as a post Civil Rights Struggle, but something that people are always contending with within these movements. And so, just like our social movements are stronger when we’re focused on the most marginalized people, our histories are also better when we do that.

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. I found your discussion of their refusal to serve in the military really fascinating, too. And their conscientious objector status. Then, the way they brought social movements into the prisons was fascinating to me. I have a step-grandfather who was a conscientious objector in World War II, which was a very marginalizing position to be in at the time. So that was really interesting to me.

But I want to just ask everyone with us here a poll question in regards to K–12 education. I want to find out how many folks learned about the conditions of those who are incarcerated in prison, or organizing rebellions in prison, or learned about mass incarceration in their own time in school. So, we have a poll that just popped up so we can find out from the educators who are with us today if they’ve learned about this or taught about it before.

All right. So those are coming in right now. Click on the poll and tell us about your experience in school. We’ll come back to that in just a second, when it’s done.

But Garrett, I was hoping you could tell us more about how you met Stevie Wilson, who is in prison right now. He was at SCI Fayette prison [in Pennsylvania], but I believe you said that he was recently transferred. Hopefully you could tell us about how you met him, and his work around prison abolition.

Felber: Yeah, absolutely. And thank you to the whole team for working with us to make sure that we get those voices on calls like this.

So, Stevie was at Fayette, had been in solitary confinement since December, really throughout much of the planning of this event, as sort of trumped up charges for his organizing inside, and he was just recently — with the help of outside agitation, people doing phone zaps and things — we got him out of solitary and transferred to Camp Hill, which is where he’ll be calling from today.

Stevie and I met, I think, maybe almost two or three years ago, or got in contact. I was a little bit frustrated, I had gotten into some of the higher education in prison work, and was realizing the way that operating between the twin institutions of the university and the prison winds up creating a lot of censorship and limitations around the possibilities for what you can teach and the types of relationships and organizing that you can do.

So, I started a program that was really building on the lessons of Ella Baker and others, that people have all the tools to organize themselves. Really, this was a program that was dedicated to sending radical books inside to facilitate self-led reading groups inside. Stevie was someone who was suggested as a host, so we got that program going, that study group was in 2018. Since then, Stevie’s been involved in all sorts of stuff, of which I’m just sort of a co-conspirator. Another thing that we spent about a year working on was a roundtable discussion on the imprisoned Black radical tradition that we did for Black Perspectives, if people are familiar with that blog, from the African American Intellectual History Society [AAIHS]. So Stevie came up with a first round of questions, sent them through me to Dylan Rodriguez and Joy James and Dan Berger and Toussaint Losier, to a bunch of folks who study prison abolition, and we did two rounds here in my area. We just continue to organize together. And Stevie can share a lot more, I hope, about the types of study groups that he runs inside.

Hagopian: Excellent. Yeah, we’re looking forward to hearing from him. So, I just wanted to show everyone the polls that came out. We have over 200 educators or community members joining us here in this forum tonight. Only 13% said that they learned about the conditions of those who are in prison in school; only 7% said they learned about prison organizing or rebellions in school; 17% said they learned about mass incarceration; 28% said they learned or taught about one or more of the above. But over 52% said they have not learned about any of the preceding questions. So I think that unequivocally shows the urgency of us revealing the conditions of mass incarceration. In a country that has over two million people incarcerated, for students not to learn about those conditions is really appalling. It really shows the need for this session today.

We had a chance to ask Stevie some questions before the session, so I wanted to turn to some of the audio that we have of Stevie. So the question for Stevie that we asked was, “What should teachers and students know about prisons and the people inside of them?” And Garrett took that question and asked Stevie and I think we have the audio ready to play.

Stevie Wilson: I want teachers and students to know that there are people, human beings, in prison. This obvious fact is often and purposely obscured by the media and politicians. We are mothers, fathers, sons, daughters, brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, cousins, husbands, wives, lovers and friends. And we deserve respect like anyone else.

Like other humans, we are imperfect. We have harmed others and have been harmed. But exiling and caging humans will not decrease harm or produce safety. In fact, it creates more harm. In the short and long term.

Hagopian: That’s so important, just to humanize people who our system is systematically trying to dehumanize. I believe I also asked if Stevie could talk about the environmental racism of where the prison is located and the racism of the response to this public health crisis, and we have the audio ready from when Garrett was able to transmit that question to him.

Wilson: I’m going to talk a little bit also about the relationship between the environmental racism of where the prison is located and the racism of the response to this public health crisis. I think Ruthie Gilmore talks about this, something a lot of people don’t realize, she’s talking about environmental racism, right? You have Black and Brown people being taken from urban neighborhoods to these toxic rural sites. At the same time, poor white rural folks are being subjected to this also, because these prisons are being situated where they live, like here at Fayette, Pennsylvania. And the people that are fighting, they are sick, they are fighting just as much as the prisons are fighting, but too often they’re fighting alone. Instead of the people fighting alongside the prisoners and the prisoners fighting along with outside people, it’s a separate movement. So what needs to happen is that they need to come together and understand that we’re all sick. There’s a higher rate of cancer in this area amongst the civilians, and amongst the prisoners, they’re both dealing with respiratory issues and skin ailments and stuff like that. So we need to understand that it’s impacting everybody.

They’re situated in these areas, in rural, poor areas. A lot of white folk, poor white folk, are in Black and Brown poor urban areas. So, you see, it’s still poor folk who have been exposed to environmental racism, but it’s poor urban folk — whether it’s poor Black and Brown or poor urban folk who will be transported to these rural areas. So there is a connection. And the thing is that they need to come together and fight alongside one another.

Hagopian: Yes, we do need to come together in this struggle. It is really inspiring to hear those words, with everybody here, that even though they have tried to lock him up and make him invisible to the world, his message is reaching us all. It’s just hitting me right now in a really powerful way. So thank you for bringing those words to us, Dr. Felber. And we want to hear from another prison abolitionist that you’ve worked with. Safear Ness. I believe he’s also currently incarcerated at saw SCI Fayette. Is that correct?

Felber: Yeah, So Stevie and Safear were both incarcerated at SCI Fayette, and now, since Stevie got transferred, Safear’s still there organizing their study groups.

Hagopian: Excellent. Well, thank you for getting the audio and the interview questions to Safear as well. I also had him respond to a question in advance about the prison’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Felber: He’s an editor for In the Belly zine, so we were posting a link to that.

Hagopian: Perfect, so people can see his work there. Now we’re going to get to hear his words about the impact of COVID-19 on the prison.

Safear Ness: I’m Safear Ness. I’m a Muslim, and a prison abolitionist currently incarcerated at SCI Fayette prison in Pennsylvania. It’s no secret that the [Department of Corrections] DOC’s response to COVID has been disastrous. It’s been a combination of traumatic lockdowns combined with negligence and screening and testing, especially screening and testing of people that are actually going to bring the virus in, which would be the COs and the prison staff. Also, testing of prisoners. How horrible. I’m on a block, and right before I moved here, COVID swept through this block. I got comrades whose cellies became sick, then they were forced to stay confined with them, and so they got sick, too. People I know over here got paperwork in right now because their cellies tests are positive for COVID and medical refused to test them. Instead, the prison chose to test sewage levels to determine if COVID cases were increasing or decreasing in the facility. What I mean is, instead of choosing to test people individually, they choose to test everyone’s feces collectively to determine how many COVID cases are in the prison.

Hagopian: Yeah, thank you. Before I move on to the next question, Garrett, if you have any comments on any of the questions that they responded to, or any more background information about either of them or the study groups that they’re organizing . . . .

Felber: Well, one, the COVID response that he’s talking about, I just want to say that that is not at all unique to that prison. It’s not at all unique to the PA DOC. Most of the folks that I’ve been organizing with over the last year through Study and Struggle in Mississippi reported similar things — of the state just refusing to test people. Essentially, their logic is, if we don’t have to show that people are getting COVID then we don’t have to deal with the problem of COVID. And, of course, in all of these states, abolitionists have worked pressing for commutations, which is firmly within the purview of the governors, and they just haven’t done it. So, I just want to say that. And then I’ll talk a little bit later, I think, about the study groups, when we talk about Study and Struggle and prison censorship.

Hagopian: Yeah, right on. I know that there are places where there were prisoners let out because of the COVID crisis, but I don’t know how that happened, or how widespread that is and if there’s anything we can learn from that. . . .

Felber: I mean, what we can learn is that until people inside are seen as human, and the public outside sees the public health crisis that’s going on outside as one that’s incredibly exacerbated by inside conditions. . . . I mean, there’s nowhere worse during a pandemic than people being warehoused, either like Safear described, two people in a cell, or the sort of mass warehousing where you have bunk beds. So, that’s it. Until we actually put enough pressure, and enough people believe that, folks. Because that’s what it is. I mean, these governors have the powers and they don’t do it, because it’s not a winning political move. So we need to organize to make that unsustainable for them.

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. It’s amazing. Like, obviously the viruses are brought in from the outside, and yet they can’t escape or control any of the conditions of their safety. So it’s particularly cruel. Thank you for sharing that.

I wanted to return to some of the lessons in your book now that I think are so important. As we think about how to get out of the prison industrial complex, how to envision a different kind of world without prisons.

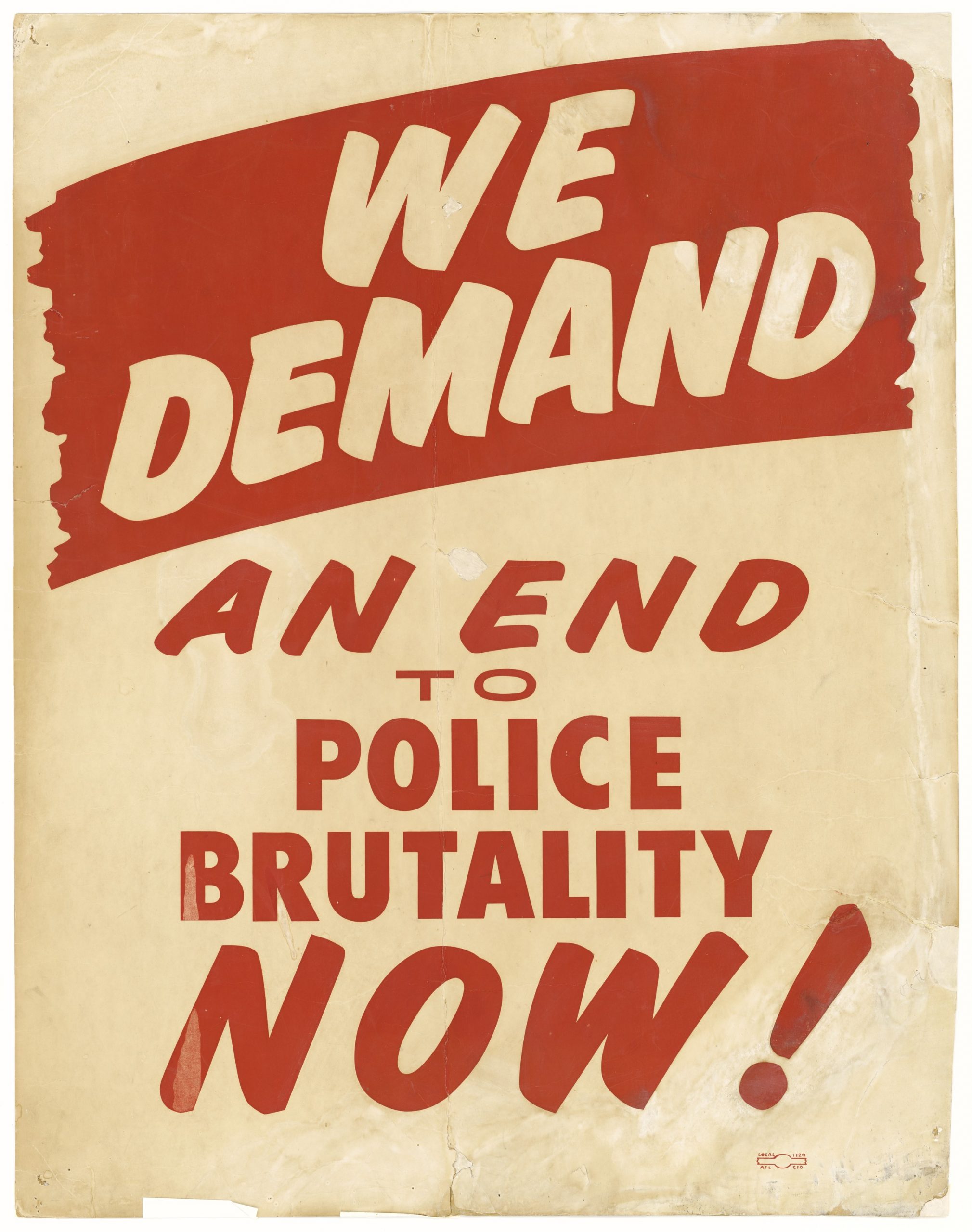

You write about the wide-ranging organizing strategies of the NOI in the book and you said, “Muslims in the Nation of Islam, confronted with police violence and state surveillance, responded with nonviolent prayer. Where do such stories fit in our narrative of the Civil Rights era?” I was wondering if you could talk more about the political strategy and the wide-ranging actions that the NOI took against police brutality and the carceral state? You write about actions they took in the courtrooms, inside the prisons, and also in the streets.

Felber: So one of these, I think the passage you’re talking about in the book is actually responding to this scene. It’s at Folsom Prison in the early 1960s and basically this group of Muslims are sitting in the yard having a meeting, and they’re under surveillance by prison guards. When they see that these photos are being taken, they sort of purposefully stand in prayer and face Mecca, and — think about in 1961, a decade before Attica, which is, I think, where a lot of people’s consciousness about the prisoners’ rights movement begins — that they’re responding to surveillance with prayer, and trying to place that again within the civil rights narrative. It just doesn’t quite fit with what we have.

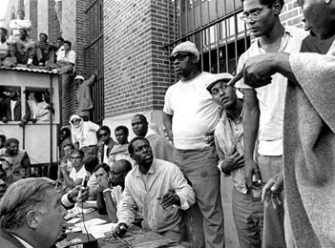

Actually, I’ll start with this story, you mentioned the streets, because I think that’s maybe a touchstone that everyone has. So, anyone who’s read The Autobiography of Malcolm X, or taught it, or seen the Spike Lee film knows the scene with Johnson X Hinton, who is beaten by police and taken to the police precinct. There’s this crowd that gathers outside the precinct, and the Fruit of Islam forms this disciplined phalanx around it, and then once Malcolm gets him transferred to the Harlem Hospital he kind of waves and everyone silently disperses. And there’s even this famous line, “no one man should have that much power,” that this cop says — and I talked about that in the book, because in both the autobiography and Spike Lee’s film, it’s this exceptional moment. And the lesson is clear, right? It’s about Malcolm X’s power. And I actually think that’s not the lesson that we should take from that.

They constantly were in front of courthouses when Muslims are being charged with, usually, resisting arrest or assault, when they themselves were the victims of police violence, they are outside police precincts. The lesson there really is not just about Malcolm’s power, but about the power of collective discipline, that all of these folks there that night gathered and scared the police. The thing that was scarier to them than an actual uprising was the fact that this uprising could be controlled in that way. And I think that’s such a powerful lesson for us to think about — collective discipline. Not just seeing Malcolm as this exceptional figure, but what that threatens. The police are obsessed with trying to understand the Fruit of Islam as this paramilitary force, because what it shows that we know that police are not disciplined — that’s part of it, right? So they actually see this paramilitary force that is disciplined, and it scares them.

The other story I’ll share is about inside the prison, and it’s about solitary confinement. So, around the same time that I’m talking about, in 1960, 1961, Muslims were being thrown in solitary confinement, Attica prison constantly, for things like prayer, legal materials. They’re starting to write writs, suing the wardens, having the Black newspapers in their cells, having religious lessons. So they’re being thrown in solitary again and again and again. And Martin Sostre and some other incarcerated organizers say, “You know what we’re going to do is we’re going to fill solitary confinement purposefully, as a way to undermine the system, the mechanism of discipline. A different type of discipline.”

What I think is powerful and interesting about this is that this is essentially the “Jail, No Bail” strategy that Southern civil rights organizers are using at almost the exact same time in Albany, Georgia. Instead of bailing people out, they’re saying we’re going to fill the jail to the point where they can’t actually use it as a mechanism of repression anymore. The point that I make in the book is not that we should say, “Okay, these are the same thing, or one influences the other. But why is it that we don’t know the story about people filling solitary confinement ten years before the Attica uprising?” So, when I make that point about the Attica uprising being the moment that we start thinking about the prisoners’ rights movement, the Attica uprising is the fruition of decades of organizing, especially by incarcerated Muslims. So, it’s thinking about, again, the centrality of people in prison as organizers, as activists, as people who are central to the mid-century Black Freedom Struggle and thinking about the reasons why certain stories we know and certain stories we don’t.

Hagopian: Yeah, thank you for centering the organizing of the prisoners themselves in all the work that you’re doing. We have just a couple minutes left here before we need to break for breakout rooms and I just thought it might be interesting, I don’t know if everybody here does know about Attica, and I wonder if you wanted to just say a word about the 1971 Attica Uprising or any other touchstone moments in prison rebellion?

Felber: For folks who don’t know, in 1971, incarcerated people took over the D yard at Attica, quickly forming, essentially, an elected government. They had representatives from the Young Lords, the Nation of Islam, different radical white folks like Sam Melville come together. Talking about collective discipline, the role of the Nation of Islam at Attica was to actually protect the hostages and make sure that the guards who were being held as hostages were not harmed. So again, thinking about that role and why that’s important.

Then, of course, the thing that I assume, if people know anything about Attica they know, which is that Rockefeller, in particular, wanted to make a point of this — he has presidential aspirations — that they’re not going to negotiate, especially on the point of amnesty. Because that’s one of the things that people inside were asking for is amnesty for the takeover. So it’s a massacre, they send in state troopers to tear gas and massacre people. Then, of course, wind up trying to frame a lot of the people who were killed as having stabbed guards and things like that.

But I think the historical question that comes out of Attica that’s really important is: 1971 is sort of the precipice before what we know as mass incarceration, so why is it that we have Attica coming after a series of rebellions? Orisanmi Burton is writing a really incredible book right now on not just Attica, but we have The Tombs Rebellion. The New York state prisons in the years leading up to Attica were in a state of constant rebellion. And they’re transferring people between prisons. That’s one of the things the prisons do to try and quell dissent is they transfer people. But, of course, what that winds up doing is accelerating it, because you’re transferring organizers who then continue to organize.

I mean, I think that’s one of the things that we really need to work through is why is it that the moment of one of the greatest rebellions in prisons, and greatest acts of state repression in response, is at the beginning of what we know as the rise of mass incarceration? I think that’s an open question to think about, how the state responds to that.

Hagopian: Excellent, thank you for breaking all that down. I think it gives us all a lot to think about [and] to discuss. In a moment, as we go into breakout rooms, we should also think about how we center prisoners in our curriculum and make them visible to our students, imprisoned people and their struggles and their organizing efforts inside the prisons. So, I’m really excited to try to examine how to do that in my own curriculum more, and excited to see what other educators come up with out of this discussion.

Maybe you can just talk about what it’s like to communicate with prisoners. What are the parameters? And how often do they get to talk, what are the restrictions, and all that?

Felber: That’s a good question. So, as you’ve seen with this, it takes a lot of planning to make sure that folks are included in conversations. Honestly, Stevie’s been one of the people who’s really pushed me on that. I think I was planning a conference a couple years ago, and I had a lot of formerly incarcerated people there. And Stevie is one of those folks who really pushes that incarcerated people be present, as well, and emphasizes the difference between being formerly incarcerated and currently incarcerated — that you don’t know what’s happening in the prison if you’re not there. And specifically, you don’t know what’s happening at any given prison in any given state. So there’s a lot of — I think we talked about prisons in very flattened terms — and there’s just a lot of different conditions, state by state, prison by prison.

So in terms of communication, [there are] lots of different platforms: some folks have access to tablets, like Stevie does, and can do email. Sometimes those take up to ten days to get through because of censorship, because every single thing that you send or is sent to you goes through a reader. A lot of folks I just write snail mail. That’s still preferred, and again, that is also censored. [Same with] phone calls, but those you’ll hear often, even on recorded calls, like “You have one minute remaining.” Those are time sensitive.

One of the really frustrating things about Pennsylvania prisons, where Stevie and Safear are, if you send mail to them, you send it to Florida. Then in Florida, they photocopy every single piece of mail and make a copy of it and send it to them. So the originals don’t go to them, number one, and two, you have to send it to Florida to go to Pennsylvania.

Hagopian: Well, yes. Thank you for that. There’s some good questions popping up in the chat. Maybe we’ll take one and hold some of my questions for later. There was a question from a STEM teacher — like science, math, technology, engineering teacher — about how do you bring these issues into STEM classrooms that aren’t social studies? And I was thinking right off the bat, well, we just had a question about environmental racism and how that impacted the present, so I’m thinking when you’re teaching about climate change and science, when you’re teaching about environment and pollution and that kind of thing, there’s an opportunity for an intersection.

Then somebody asked a question about using prison centered language. That could be interesting to respond to. And then I’m seeing a question here — oh, the chat is moving so quickly. How do you consider your positionality in this work and your interactions with incarcerated people, and how do you intentionally address the disparate power and privilege of your position versus the folks you work with?

Felber: I’ll try to address both those questions about language and positionality. Again, there’s not like one set. . . . I don’t think everyone agrees about language, right? For the most part, folks in the movement don’t use the language of the state, like inmates, facilities, the sort of euphemisms that the state creates to hide what it’s doing.

And yeah, it’s usually person centered. So you say incarcerated people, imprisoned people. Again, emphasizing Stevie’s point that it’s people who are inside. I still use the term prisoner, and I know other folks who do, in part, because it’s a descriptor of what the state is doing. It’s imprisoning people. So you could use imprisoned person, but it’s not a term that the state uses. The state does not use [the term] prisoner because they don’t want to draw attention to the fact that that’s what they’re doing. They use euphemisms. I know in Oregon it’s Adults in Custody, AIC.

Then in terms of privilege, I mean, yeah, it’s something I think about every single day in what I do. And in part, I’m trying to use my position as a way to redistribute resources, to draw attention to issues, to work with people inside. For the most part, the people I work with inside, we’re organizing together. It’s not like a research relationship or something like that. It’s us organizing for PIC abolition. And things like tonight, trying to use this platform as a space for Safear and Stevie to have access to it and to have their voices heard. Things like that.

Hagopian: I think there’s a follow-up question. How do we center the voices of those involved and avoid a savior complex and interpret the role of toxic masculinity in mass incarceration? I saw that in the chat.

Then there’s questions about resources to learn more about this. Then, specifically, children’s texts. So I bet there are educators on here that know more about children’s texts as well. But, if you have any thoughts on any of those questions, and then we can move to a couple of others we have, if Stevie hasn’t called in yet.

Felber: I was going to say Missing Daddy is a children’s text by Mariame Kaba. I don’t know if that’s shown up yet, but that’s one that I used in the past.

Hagopian: Yeah, that’s a great one. Everybody should get that book, kids, teachers, younger kids. Even older youth, I think, will get a lot out of that book, for sure. Well, I guess if Stevie hasn’t called in, we can stop anytime he calls if he’s able to join us, but I also was hoping that you could comment on attacks from academic institutions and state legislatures on teaching about these kinds of topics and antiracist pedagogy and activism that you think is important to know about right now.

Felber: Sure. I’ll say this with the caveat that you all know better than I do, for folks who are especially K through 12 educators, what that looks like and how to fight that. But I saw most recently in Idaho, I think, there’s a bill attacking this critical race studies, which the right is now very interested in and has no idea what that is.

In part, it connects to the thing that we were talking about earlier with the Nation of Islam, actually. I was just thinking about how this idea that speaking out against racism is somehow racist, how this claim of reverse racism goes back to the way that the Nation of Islam was denounced. They talk about The Hate That Hate Produced, which is this whole introduction of the Nation of Islam to white people that’s meant to essentially say Black Nationalism is actually reverse hate. We see that same kind of rhetoric deployed now.

The other thing that I wanted to bring attention to is, again, what Stevie’s dealing with, which is all of the attacks that we see from state legislatures on antiracist education and universities. It’s happening in a much more acute and condensed way in prisons. So part of the reason that I spend so much of my time just getting books inside is that Stevie and I are working on a zine project right now that translates academic texts into zine form, one, because they’re more accessible, and two, because you can get them inside more easily.

But just a couple days ago, he had 14 books that were banned, that [Stevie was] sent. And these are things like, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freedom is a Constant Struggle by Angela Davis, Black Power Afterlives. And it’s the same logic. So I wrote down some of this. These are the direct quotes. Freedom is a Constant Struggle they didn’t let in because they said it’s a security threat group, BPP, Black Panther Party and KKK. So this idea that the Black Panthers and the KKK are somehow mirror images of each other. Pedagogy of the Oppressed says it fights to destroy causes, revolution, or transform, or promote a climate of hopelessness. So obviously, these people aren’t reading that book, because we all know Pedagogy of the Oppressed does nothing if not create hope. But all of these are said to be creating danger in the prison.

I don’t know if you all have that photo that I sent earlier of the prison library. It looks like. This is Stevie and I talking earlier today, on video chat. If you can see the thing that he’s pointing to with his pen, that black bin is the library for his entire block. That’s the whole library for that block for the last year. And he was talking about how with COVID, they’ve opened up the gym, but not the library. So not only are we talking about the repression that’s happening to Stevie in terms of what books he can get in, but that’s also the whole library! So, part of this is kind of a push for me to say all the things that you’re concerned about with your students and the world outside is happening 100-fold for folks whose experiences, especially with formal education, have been largely carceral to begin with, who have been shut out of formal education and continue to be. So, I think it’s something that we should all care about and be pushing for, and against prison censorship, making sure books get inside, supporting study groups inside.

Hagopian: Yeah, it’s outrageous that that’s the only access to books that they have can fit in that and then I guess what books are in there. I was thinking about that question, about women and imprisonment, and thinking about this book Invisible No More that I’ve learned so much from — with the introduction by Angela Davis — written by Andrea Ricci, and police violence against Black women and women of color comes to mind. But, also, there are so many issues facing incarcerated women as well that are worth studying and bringing into the classroom, especially around health issues and childbirth in prison, and all kinds of injustices that they face as well.

Felber: As long as we’re grabbing books off of our shelves, I also recommend Captive Genders for folks who haven’t come across this book, and just thinking about the way that the PIC specifically targets non-binary and trans folks. I think it’s so important to think about the way the prison constructs gender. So, what are the experiences of trans and non-binary people in prisons who are then classified? And then this sort of new neoliberal gender responsive prisons. As if that’s the answer, right? It’s another form of cooptation by the state.

So yeah, a lot of the stuff. We haven’t gotten into Study and Struggle with most of the folks who are in our study groups in Mississippi or at the state designated women’s prison, which includes trans folks.

Hagopian: Thank you so much. I have not read that book, but I will add it to my list. It sounds fascinating and important to bring into the classroom. I think that leads us to a question about Study and Struggle. Can you talk about this initiative that you’re part of?

Felber: Yeah, absolutely. I should just say, I still haven’t heard from Stevie. So it might be all sorts of things. So Study and Struggle grows out of that earlier effort that I talked about to support self-led radical study groups in prisons. We have about 150 people who are participating in radical study groups year round in Mississippi prisons.

What we do is we support them by sending the books, the materials, and the curriculum inside. We put money on people’s commissary, so they have money for letters and stamps, and food and drinks and things. Then from September through the end of the year we have a more robust curriculum where people are connected through a pen pal program with outside groups. So, anyone on this call could host a group and participate in a four month bi-weekly study group where you’re connected with people inside and are studying the same things.

We also have a webinar series, we call it Critical Conversations, once a month, where people talk about the themes for the month, authors, organizers, and then we send those transcripts inside. It’s also a fully bilingual curriculum, so it’s in Spanish and English.

Hagopian: Wow, I love it. That’s such great work.

Felber: Also, one of the things that we’re really trying to do this coming fall is make it more accessible for K through 12 [educators]. So thinking about building a curriculum, and it’s all online for free, so it’s all PDF form.

Hagopian: That’s so important. We’ll look out for that, and hopefully be able to work and help disseminate some of that. I’ve been thinking about how I could get more involved with reaching out to supporting prisoner organizing, too. So I appreciate that.

Unfortunately, you know all the barriers for imprisoned people to reach the outside world. So, we have not heard from Stevie yet, but we do have another recording with commentary from Safear Ness about what should happen to prisons that we can play.

There are people asking about lesson plans for teaching about mass incarceration, and we definitely have some important lessons in the book Teaching for Black Lives and also on the Zinn Education Project website. In the book I helped co-edit called Teaching for Black Lives, we have lessons about the prison industrial complex, we have an interview with Michelle Alexander about the school-to-prison pipeline. That is a really important document you can use to help inform your pedagogy, but also you can have your students read that interview and learn a lot from it. There’s also a really powerful lesson in the book Teaching for Black Lives that is written by a high school student. She explains her experience with having her father incarcerated and the trauma that that inflicted on her growing up, and then her own experience with law enforcement and juvenile detention. So, those are really critical lessons, I think, for engaging our youth in these discussions.

I think we can move to playing the commentary from Safear Ness about what should happen to prisons. Then, Dr. Felber, if you have any closing comments when that’s done.

Ness: The only humane prison is a prison that doesn’t exist. That’s true. As a society, we have to start dealing with our problems by not putting people in human cages. Get people on the street, give them resources that they need, give people job security, get people homes, give people access to adequate medical care, give people access to drug treatment, give people access to all of these things, and you’re going to see your communities become safer. Keep putting poor people in prison and you are going to keep getting the same result.

Hagopian: That’s absolutely right. I mean, the abolition of the prison industrial complex isn’t just about getting rid of these cages, it’s about reinvesting that money into our communities, into schools, into health care, into housing for all so that our communities will thrive and we won’t need those facilities at all. So, Dr. Felber, I don’t know if you have some closing words for our educators about what they can do and should be thinking about as they go back to the classroom.

Felber: Yeah, I was frantically trying to find this, but if anyone knows of it and could link it in the chat, so Mariame Kaba, I think at the beginning of this year, had a really handy nine things that you can do if you’re making a commitment to PIC abolition. They were things like phones zaps, writing to incarcerated people, mutual aid. So I think there’s a lot of ways for people to get connected, whether it’s supporting someone inside, asking what folks need, doing mutual aid with local community groups, things like that.

I think often it can seem like a really intimidating thing to get involved in and it seems like it’s just about the prison, right? But the PIC is this sprawling thing. I mean, if you work in schools you know how the carceral system touches schools. So no matter where you are, there’s some way that our punishment system is touching your life. And if it’s touching your life, that’s a space to organize. That’s what I would say.

Then the myth that Safear mentioned that prisons make us safer. Prisons are not about making us safer. They are the leading perpetuator of harm. And I think we have the link to Stevie’s written comments [see below]. So that’s something that people can check out, too. Stevie makes this really important distinction — and a lot of abolitionists do too — between harm and crime. That’s something that I encourage you to check out

But, as an opening with your students, if you want to just talk about the difference between crime and harm, that’s a really great conversation, because so often we think about those things as the same. But crime is a social construct, it changes over time. Harm is something that all prison abolitionists are concerned with. But that’s not the same thing as crime. Again, you can do this similar exercise when thinking about the difference between punishment and accountability. And this is a point that Mariame Kaba makes all the time, that when we talk about accountability we’re often mistaking that for punishment, and those are not the same things. Accountability requires that the person actually wants to be held accountable, otherwise, you’re just inflicting punishment upon them. So I think either of those work. In theory, the difference between punishment and accountability, or harm and crime, are good ways that you can just open up a conversation about the logics of the carceral state that we too often take for granted.

Hagopian: Yes, absolutely. Thank you. And thank you for lifting up Mariame Kaba’s work. Everyone should read her new book, We Do This ‘Til We Free Us. Also, there’s a playlist that goes with that. I think we might hear some cuts from that, but you can find that playlist on Spotify. And if you’ll notice in the chat, there’s a link to Miriame Kaba’s commitments and also to Stevie Wilson’s written response to the question. So you can hear more from him there as well. I just want to thank you deeply, Dr. Felber, for joining us today and for helping us hear the words of incarcerated people, and deep thanks and please send our gratitude to Safear and to Stevie.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Additional Resources

Here are many of the resources recommended by the presenters and also by participants.

Lessons and Curricula |

||

|

|

|

What We Don’t Learn About the Black Panther Party — but Should “Riots,” Racism, and the Police: Students Explore a Century of Police Conduct and Racial Violence Teaching Social Activism in Prison: The Leap Manifesto and Incarcerated Youth Attica Prison Uprising Resource List |

Related Books and Articles |

||

|

||

|

A People’s History of Muslims in the United States: What Textbooks and the Media Miss All Our Trials by Emily Thuma Chained in Silence by Talitha LeFlouria Dreaming Freedom, Practicing Abolition Blog, featuring Stevie Wilson and others. |

“Imagining a New World Without Cages”: Interview with Stephen Wilson Invisible No More – Police Violence Against Black Women by Andrea Ritchie, with intro by Angela Davis Rethinking the American Prison Movement by Dan Berger and Toussaint Losier See more books on the Social Justice Books Incarceration list, including Missing Daddy by Mariame Kaba. |

|

Films |

||

|

Abolition 101 taught by Orisanmi Burton. Defund Police by Project NIA Malcolm X: Make It Plain by Steve Fayer and Orlando Bagwell Slavery by Another Name by Sam Pollard, Catherine Allan, Douglas Blackmon, and Sheila Curran Bernard |

||

Projects and Organizations |

||

|

|

|

Books Through Bars Sends books to incarcerated people across the nation at no cost to them. Free Ashley Diamond Campaign to free Ashley Diamond, a Black and trans woman, from prison while raising awareness about the prison industrial complex. Free Minds Book Club & Writing Workshop Uses the literary arts to connect incarcerated and formerly incarcerated youths and adults with community. The Jericho Movement Raises the voices of political prisoners and works for their amnesty and freedom. Project NIA Works to end the arrest, detention, and incarceration of children and young adults by promoting restorative justice practices. Photo Requests From Solitary (SolitaryWatch.org) Invites people held in solitary to request a photo and finds an artist to fulfill the request. RAPP: Release Aging People in Prison Campaign Works to end mass incarceration through the release from prison of older people. Study and Struggle Coordinates resources to fight criminalization and incarceration in Mississippi. |

Podcasts |

||

|

|

Millennials are Killing Capitalism Rustbelt Radio: “Abolitionist Study with Steve Wilson” |

This Day in History |

||

|

Feb. 21, 1965: Malcolm X Assassinated Sept. 9, 1971: Attica Prison Uprising Oct. 11, 1972: D.C. Jail Uprising Oct. 27, 1994: U.S. Prison Population Exceeds One Million See more This Day in History stories about the police. |

||

Q&A with Stevie Wilson and Safear Ness

Here are responses to Jesse Hagopian’s questions (JH), sent in advance by Stevie Wilson (SW). Safear Ness’ answers are further down.

JH: Stevie, you are imprisoned at SCI-Fayette, a prison located on a toxic waste dump south of Pittsburg, and you have been a vocal critic of the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections’ weak response to the outbreak of COVID-19. Can you tell us about your experience working to raise money for hygienic products for imprisoned people to slow the spread of COVID? Could you talk about the relationship between the environmental racism of where the prison is located and the racism of the response to this public health crisis?

COVID created an opportunity for the work to increase. Prisoners displayed a much more cooperative mindset than usual. We understood that we needed each other and our allies to survive the pandemic. So there has been something positive out of this pandemic: more connections between prisoners and their allies.

The PA DOC, like most Departments of Corrections in the United States, wants to monopolize the flow of information between the walls. So whenever a prisoner talks about what is really happening behind these walls, he or she becomes a target for repression. It is expected.

Ruthie Wilson Gilmore writes about the real connection between where many incarcerated folks are drawn from and where we are deposited. Both of these sites have similar characteristics that organizers and activists within them fail to grasp. Instead of creating strategic coalitions to fight against environmental injustice, they often go it alone. The State Correctional Institution at Fayette (SCI Fayette) is located in LaBelle, Pennsylvania. The prisoners as well as the residents of the town experience much higher rates of cancer, respiratory problems and skin ailments. But they haven’t joined forces. The work would be more effective if they did. Both populations are suffering. And the culprit is the same.

JH: Can you talk about the terminology related to the prison industrial complex?

Crime

SW: We rarely use the word “crime” in our work. We understand crime to be a social construct: something those in power in a society deem criminal for the time being. We know that what is criminal depends upon who, what, where and how.

We know that a Black person learning to read was once a crime here. So were simple things like standing on a corner in a southern state. So we understand how the category crime is used to control people and produce certain outcomes favorable to those in power.

We also understand harm to be something much broader and experienced and perpetrated by everyone. We know that people are harmed in many ways that are not considered criminal. We understand how our environment is repeatedly harmed and no one is held accountable. I believe if people began to think about harm and nix crime, we will be able to make headway in creating truly safer communities.

If we all become more aware of the ways we harm others everyday, and work to eliminate these practices, our world will be more equitable. This produces better relations, which produces safety.

Also, we must be aware of the ways the media hypes crime, creates criminals and naturalizes the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) Recently, I asked people to flip through their TV channels and count the number of programs that focus on crime, courts, police, or incarceration. You would be surprised at the number of programs being pushed our way that legitimize the PIC. This is part of cultural criminalization.

Policing

SW: Here’s the point: more police equals more crime. Whenever and wherever police presence increases, the number of arrests increases too. This is the only correlation supported by data. Crime and incarceration rates don’t correlate. In this country, crime rates fell, but incarceration rates rose. Why? Because there were more cops in the streets, occupying urban neighborhoods. You know why the arrests and crime rates are lower in the suburbs? Because police presence is lower.

I would like the students to think about what is happening and has recently happened regarding protests and the state’s response to them, especially the difference when Black folks protest and White folks form an insurrection.

I think they can clearly grasp whom law enforcement is focused on and has always been focused on. I think they can understand the state’s reaction to any questioning of its monopolies on violence and its authority to eliminate those that challenge its oppression or those who are expendable within its plan for global domination.

Why are the people protesting? Why is law enforcement responding the way it is? Who is being served? Who and what is being protected?

JH: What did you learn — or not learn — about the Black Freedom Struggle in school? What moments of the Black Freedom Struggle have you learned about that you take the most inspiration from today?

SW: In school, I didn’t learn much about the Black Freedom Struggle. I learned about the Civil Rights Movement, but it was presented as the heroic efforts of a few cis-het men, not a mass movement. It wasn’t until I was incarcerated that my knowledge of the Black Freedom Struggle and its many participants become known. And this was through study, not the Department of Corrections.

JH: What should teachers and students know about prisons and the people inside them?

SW: I want teachers and students to know that there are people, human beings, in prison. This obvious fact is often and purposely obscured by the media and politicians. We are mothers, fathers, sons, daughters, brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, cousins, husbands, wives, lovers and friends. And we deserve respect like anyone else.

Like other humans, we are imperfect. We have harmed others and have been harmed. But exiling and caging humans will not decrease harm or produce safety. In fact, it creates more harm. In the short and long term.

JH: What does being a prison abolitionist mean to you? How did you come to be an abolitionist?

SW: I am a penal abolitionist. I want to see the elimination of the prison industrial complex. I want to end all systems of domination and oppression. I want to build a world in which the dignity of everyone is upheld.

I worked in human services for a long time, specifically HIV education and prevention. For so long, I was frustrated by the lack of real results, real material changes, in the lives of the people we were supposedly advocating for and serving. No matter what I did to remedy things, the system thwarted me. It couldn’t be reformed. I gave up. When I was introduced to abolitionist theory, I realized the system was the problem. I had never imagined solving these or any problems outside of the established systems. When I understood that we could, and that people already were, not only challenging the systems, but also creating other ways of caring, living, and relating, outside of the oppressive systems in this culture, I knew this was for me. I found home.

JH: Tell us about the different study groups you are a part of and their relationship to the organizing work you do.

SW: The largest group is the 9971 study group (Ask them if they know why it’s named 9971). It’s an abolitionist study group. It’s the door for many people new to the work.

SASS (Smithfield Abolitionist Study Squad) was started as a space where queer and trans incarcerated folks could study abolition and apply it to the particular lived experiences of queer and trans folks.

Circle Up is a transformative justice study and healing circle Book Club. We have been fortunate to connect with book publishers, including Haymarket and UNC Press, who support are political education efforts inside by providing books to members. We hope to expand this project. Usually, the book clubs have 10 members.

All of the study groups are critical parts of the organizing being done behind the walls. It’s in the groups that we become aware of issues, study them, and formulate plans of actions. So without them, we wouldn’t get much done. And the DOC knows this. This is why they oppose our study efforts. Moreover, liberation will only come about collectively. And the study groups teach us how to be in community. For many of us, the feeling of belonging to something larger than ourselves is new. We learn how to be in community by way of the groups. Organizing is collective and the study groups greatly assist that collectivity.

Safear Ness

Additional responses to the questions were provided by Michael “Safear” Ness (he/they). Ness is a white/Mexican Muslim practicing prison abolition at SCI Fayette in Pennsylvania. Safear grew up in Philadelphia and has spent all of their adult life under various forms of carceral supervision. Although they are held captive, they have transformed their cell into a learning center. Education is now their weapon of resistance. [Bio from AAWW.]

I’m Safear Ness. I’m a Muslim, and a prison abolitionist currently incarcerated at SCI prison in Pennsylvania. It’s no secret that the [Department of Corrections] DOC’s response to COVID has been disastrous. It’s been a combination of traumatic lockdowns combined with negligence and screening and testing, especially screening and testing that people that are actually going to bring the virus in, which would be the COs and the prison staff. Also, testing of prisoners. Now horrible. I’m on a block and that right before I moved here, COVID swept through this block. I got comrades whose cellies became sick, then they were forced to stay confined with them. And so they got sick, too. People I know over here got paperwork in on right now because their cellies tests are positive for COVID and medical refused to test them. Instead, the prison chose to test sewage levels to determine if COVID cases were increasing or decreasing in the facility. What I mean is, instead of choosing to test people individually, they choose to test everyone’s feces collectively to determine how many COVID cases are in the prison.

And overall, I think it highlights the bigger issue and the overall picture is that prisons, you know, don’t prevent harm in society. They don’t prevent harm. If anything, prisons only increase harm. People don’t come to prison — it’s like this myth out there — that people think people come to prison and get the healthcare that they need, and get the “mental health” resources they need and get, you know, the drug addiction treatment that they need — that does not happen in prison. I’ve been in this prison going on seven years. I’ve been in their drug treatment program. You know what I mean. I’ve seen people try to get “mental healthcare.” Their “mental healthcare” is drug prescriptions only. Like, stuff is not what you think it is. It’s not what you think it is. It’s no care and concern here.

You know, and that’s why the only humane prison is a prison that doesn’t exist. That’s the truth. As a society, we have to stop dealing with our problems by putting people in human cages. You know, give people on the streets the resources that they need. Give people job security. Give people homes. Give people access to adequate medical care. Give people access to drug treatment. Give people access to all of these things and you’re going to see your communities become safer. Keep putting people in prison — prison hasn’t been working. Keep putting them in prison and you’re gonna keep getting the same results. You know, and that’s it. That’s it. That’s all I got.

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

Over 2 million people are incarcerated in the United States, yet within school students minimally learn about the prison system and the life of an incarcerated person.

Hearing about the Nation of Islam’s facility and role in prison organizing. Also, how well-organized prisoners and prisoner groups are.

The importance of centering the voices of incarcerated people when teaching about the PIC

The idea that it is time to bring discussions of incarceration into my classroom seems imperative.

The most important thing I learned today was how this is an important issue that is not brought out by the media or curriculum taught in schools. Mass incarceration is a serious problem that we face in this country and we as individuals can play a role to address this issue and work towards prison abolition.

That I’m not alone in my wish to teach this.

That other educators at all levels see this as curriculum-worthy! Yey!

The power of organizing though incarcerated and the imperative to organize wherever we are.

The limited awareness of educators (as evidenced by the poll) about the prison system and incarceration despite the very evident school-to-prison pipeline that is present in the majority of our schools

I truly appreciated the connection between the dehumanization of people who are imprisoned and prison rebellions.

The juxtaposing of crime v. harm, punishment v. accountability is something that needs investigation and contemplation.

I didn’t learn anything new today, but I was very glad to hear from incarcerated folks from my city (Philly). Their stories are so common here. Almost everyone I know has had a family member incarcerated in an SCI facility. Several of my students are currently imprisoned on State Rd (A Philly prison).

Incarcerated persons are humans and their organizing and stories matter.

What will you do with what you learned?

As a teacher educator, I want to consider ways to support my future teachers in thinking about how many students/children may be impacted by a loved one who is incarcerated.

I am in the process of reimagining my whole course and planning how I will teach Civics, and this will inform that process for sure.

I need to think a bit more about where this can come into my curriculum, but I think it has sparked me to learn more.

I will share my thoughts and knowledge that I learned and ensure that I apply what I learned to my future classroom and pedagogy.

PIC will be part of my Climate Justice teachers class.

I am going to continue my learning with the resources mentioned and incorporate this learning into the learning taking place in my classroom!

I am going to find more children’s books that aim to humanize incarcerated people and have critical conversations about how incarcerated are represented in texts.

I will take all of the incredible resources in the chat and from the speakers and educate myself and others. I will try to get my school involved with the Study Groups.

I work in a community where we have been talking about people who are imprisoned but when I think more critically about it. Often, the humanization is focused on those who are wrongly convicted. I had not made this connection until this evening and this is a huge shift we need to intentionally make in language, focus and curriculum.

I want to find at least two tangible ways I can become directly involved with prison abolition and find at least one way I can bring this conversation to my school campus.

I will use ideas to try to incorporate the information in my teaching. Since I work with very young students, K through three, and I teach reading, I have to be creative. But there are lots of ways to do that. I can introduce books, passages, and videos to spark discussion and or writing. I will work on this.

I will use some of the resources that were discussed during the session and the break-out group. I really appreciated the way teachers were sharing resources in the chat. The discussion also made me think about the inherent shame and marginalization of the incarceration experience and how we can combat that in our classrooms. I would also be interested in resources specifically geared towards incarcerated youth.

What did you think of the format?

Breakout rooms and hearing from the incarcerated people was awesome!

I appreciated the format and not being pressured.

All worked. I really appreciate the recorded responses from the two activists, providing perspectives from people currently incarcerated.

Everything was great. I especially value the modeling of the importance of students processing their learning.

A bit more time in breakout rooms would be great as well as closed captioning. Otherwise, the introductions in the chat were great, the questions for the speaker were pretty organized and clear, although I think choosing one question from the chat at a time to pose would help clear ideas up. Breakout rooms were phenomenal, there were so many powerful ideas shared that made me really think.

Our facilitator was great — even with a group where many people were quiet. She was inclusive, prompted the group, and provided time and space for those who needed it. Well done! I really appreciated having the group — having even ten minutes to connect was so important to making meaning for ourselves. Thank you for embracing strong pedagogical practices!

I appreciated the break-out room. A 4th-grade teacher shared how people are worried about talking about slavery or racism but they are ok with sharing all the atrocities the Nazis did — pointing out that it’s easy to talk about being on the good side of history. And she shared some resources that were useful to her, which I believe ended up in the group chat. That was GREAT.

I really enjoyed the break-out rooms with people from all over the country!

Additional Comments

I really appreciated being able to hear the voices of those who are incarcerated and their perspectives.

Such a great class and wish that we got to hear from Stevie about his experience. I wish there were more classes focused on this topic and the connections to the Black Lives Matter demands.

Every time I attend one of these sessions I learn something new.

It was so wonderful to be in the same space as so many like-minded people who are passionate about these injustices and proactive in their learning and activism.

Thank you — I was exhausted after a long day and almost didn’t make it in time. I am so glad I did — I am leaving with more energy and enthusiasm than I started with. That is always a good sign of a great learning opportunity. Thank you!

So grateful to the Zinn Education Project for bringing ignored topics about how to better all people’s lives by paying attention to hard issues. The work you do is invaluable to all of us and to the country.

Perhaps this topic can be a day-long professional development where groups could create lessons, research resources, and take away materials that could create used right away. Educators could be grouped by grade level or by subject matter.

Presenters

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, and editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing.

Stevie (Stephen) Wilson is an incarcerated prison organizer and educator. Read about Wilson’s work in the blog he authors, Dreaming Freedom, Practicing Abolition. Listen to an interview with Wilson on Rustbelt Abolition Radio to learn more about his work and perspectives.

Safear Ness is a white/Mexican Muslim practicing prison abolition at SCI Fayette in Pennsylvania. Safear grew up in Philadelphia and has spent all of their adult life under various forms of carceral supervision. Although they are held captive, they have transformed their cell into a learning center. Education is now their weapon of resistance.

Garrett Felber, author of Those Who Know Don’t Say: The Nation of Islam, the Black Freedom Movement and the Carceral State, is project director of the Parchman Oral History Project and was the lead organizer of the Making and Unmaking Mass Incarceration conference. He co-founded Study and Struggle, a project that organizes against criminalization and incarceration in Mississippi through mutual aid, political education, and community building. They provide a bilingual Spanish and English curriculum with discussion questions and reading materials, as well as financial support, to over 100 participants in radical study groups inside and outside prisons in Mississippi.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn