Ten students from Southwest Texas State University (now known as Texas State University) were suspended and their course credits were erased for participation in a peaceful anti-war protest on their campus on Nov. 13, 1969. They appealed their case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which let the lower court’s rulings, upholding their suspension, stand without rendering a decision on them. The San Marcos 10 lost all credits earned during the 1969-70 school year and their official transcripts read “The U. S. Supreme Court has ruled for the administration and all credit is denied.”

Ten students from Southwest Texas State University (now known as Texas State University) were suspended and their course credits were erased for participation in a peaceful anti-war protest on their campus on Nov. 13, 1969. They appealed their case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which let the lower court’s rulings, upholding their suspension, stand without rendering a decision on them. The San Marcos 10 lost all credits earned during the 1969-70 school year and their official transcripts read “The U. S. Supreme Court has ruled for the administration and all credit is denied.”

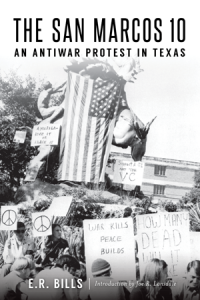

E. R. Bills, author of The San Marcos 10: An Antiwar Protest in Texas (History Press, 2019) provides a detailed description below.

By E. R. Bills

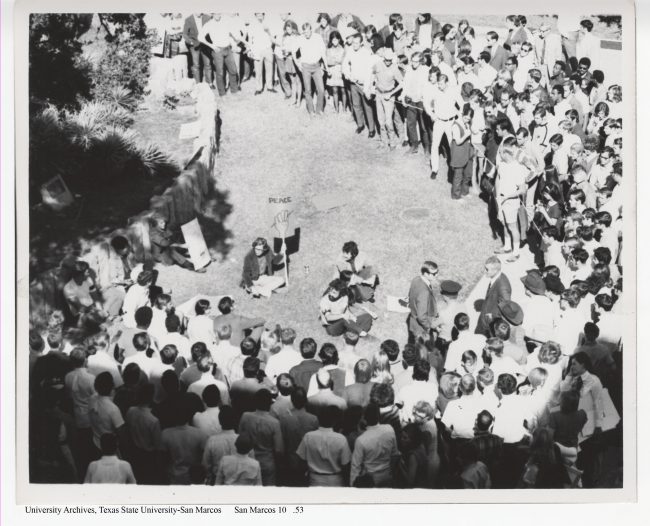

At around 10:00 a.m. on Nov. 13, 1969, a group of students at Southwest Texas State University (now known as Texas State University) staged an anti-war protest in front of the Huntington mustang statues just off the main quad. They sat cross-legged and pensive, some wearing black arm bands to mourn the U.S. war dead and some carrying signs. One of the signs said “Vietnam is an Edsel.” Another noted “44,000 U.S. Dead, For What?”

News of the My Lai Massacre had just been released the day before.

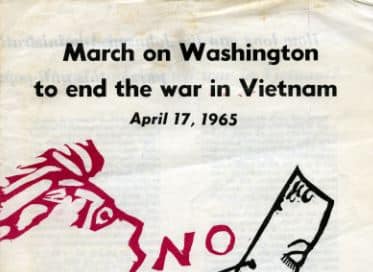

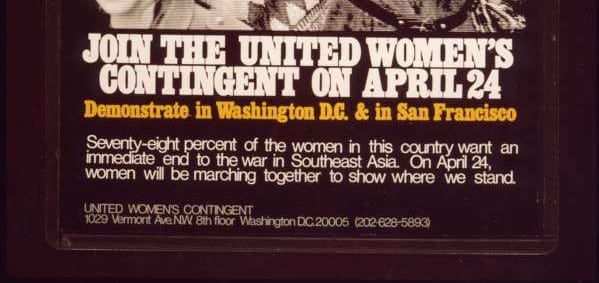

The coming weekend would mark the second national anti-Vietnam War Moratorium and over 250,000 people would march on Washington, D.C. Less than 75 sat silently around the Huntington mustangs on Nov. 13, and they weren’t causing a disturbance.

At approximately 10:35 a.m., a university official showed up, surrounded by an entourage of rodeo types and football players. He gave the following ultimatum:

Ladies and gentlemen. May I have your attention please? I am Floyd Martine, Dean of Students. In the judgment of the university administration, this assembly is a violation of established university policies as set forth in the Student Handbook. I hereby direct you to leave this area within three minutes. Any student remaining beyond that time will be suspended from school until the fall of 1970.

Martine repeated the statement, gave the group three minutes to clear out and then left.

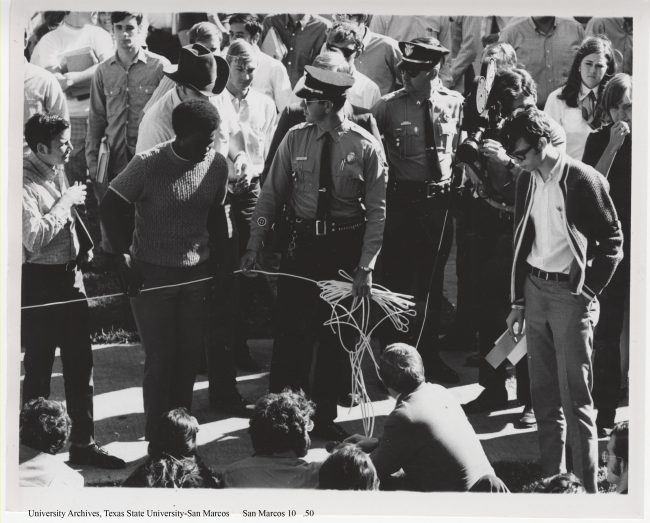

As campus security officers began roping off the area, most of the demonstrators dispersed; but a handful remained. In the meantime, the crowd outside the rope had increased, bolstered mainly by a “My country right or wrong!” and “Love it or leave it!” contingent. They taunted the remaining anti-war protesters and became threatening. A German instructor subsequently stepped under the rope and joined the protesters.

When Martine returned, he found ten students and the German instructor sitting around the base of the Huntington mustangs. Amidst jeers like “Your three minutes are up” and “Let’s drag ‘em off,” Martine told the protesters they were “through at the university” and began taking names.

The remaining protesters, who came to be known as the San Marcos 10, were 27-year-old, Vietnam veteran David G. Bayless of Silver City, New Mexico, 19-year-old Frances A. Burleson of Houston, 23-year-old Paul S. Cates of San Antonio, 19-year-old Arthur A. Henson of Pasadena, 23-year-old Michael S. Holman of Austin, 27-year-old David O. McConchie of Wimberly, 24-year-old Murray Rosenwasser of Lockhart, 21-year-old Joseph A. Saranello of Brooklyn, New York, 20-year-old Sallie A Satagaj of San Antonio and 18-year-old Frances A. Vykoukal of Sealy. They were suspended immediately. No action was taken against Allen Black, the German instructor.

The San Marcos 10 were not alone. On November 13 at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, 10% of the student body wore arm bands, but only half of that percentage wore black. The other half wore red, white and blue armbands (distributed by a counter-moratorium group referring to itself as the Silent Majority). At Southern Methodist University in Dallas, a group of anti-war demonstrators delivered speeches and read a list of the 2200 Texans that had been killed in Vietnam on the steps of Dallas Hall. The SMU protesters also constructed a mock graveyard to commemorate the Texas casualties. Around the rest of the city, Dallas ISD sent home twenty high school students for wearing black arm bands.

In Beaumont, Lamar Tech (now Lamar University) faculty members held a teach-in and four African-American students from a local high school were arrested for circulating an anti-war newspaper. In Waco, a hundred students attended an anti-war rally in Cameron Park.

The San Marcos 10 hadn’t given speeches, passed out literature, read lists of the Texas war dead or built mock graveyards. They had simply taken part in a peaceful demonstration, and it wasn’t their first.

The first national Anti-Vietnam War Moratorium had occurred a month before on October 15. Texas State students had participated in it at the very same location and there were no complaints or repercussions.

The first demonstration had been a success and probably gathered much more attention than university officials were comfortable with, especially since Texas State was former President Lyndon Johnson’s alma mater.

Regardless of motive, Texas State officials had decided to obstruct the November protest by reducing its visibility as much as possible. Martine restricted protests to a designated “free speech area” away from the central quad and forbid demonstration assemblies before 4:00 p.m. on weekdays.

Before the Nov. 13 sit-in, protest organizers had spoken with two attorneys recommended by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to determine their rights. The concluded that they a First Amendment right to hold another protest in the original location as long as they didn’t block quad traffic or create a disturbance.

On the evening of the San Marcos 10’s suspension, hundreds of their classmates and faculty members marched on the Administration Building protesting the 10’s treatment. The next morning they reappeared and Texas State President Bill Jones told a group of student representatives the university “means to hurt no one.”

“After all,” Jones said, “we are here for the same purpose — education.”

After their suspension, the San Marcos 10 met with lawyers again and instituted procedures to file a grievance. They fought their dismissal through school channels, presenting their case to the Student-Faculty Board of review, Jones, and the Texas State University System Board of Regents. Their appeals were denied at every level.

The 10 then took their case to federal court. The ACLU filed a $100,000.00 damage suit against Martine, Jones, and Texas State University, maintaining that the university et al had “created a policy which violates the rights of freedom of speech and assembly granted under the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.”

The 10 asked for a temporary restraining order prohibiting suspension prior to a final hearing in court (allowing them to return to classes), a permanent injunction preventing the university from making notations on their permanent records and a declaratory judgment that the Student Handbook policy dealing with student expression be void because it was characterized by vagueness and over-breadth.

In early December, U.S. Federal Court Western District Judge Jack Roberts denied the 10’s appeal for reinstatement but did not rule on the merits of the case, noting that “no party denies that the First Amendment applies with full vigor on the campus, but a university by reasonable regulation, can limit and regulate the exercise of rights granted by the Constitution. . .”

The 10 immediately appealed the Roberts’ denial to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans and, on December 13, the 5th Circuit temporarily blocked the students’ suspension “pending the disposition of this appeal and subject to further orders.”

Under the conditions of the injunction, the San Marcos 10 finished the fall semester of 1969 and the spring semester of 1970. But in the summer of 1970, the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals found in favor of Texas State University, ruling that the school had acted within its rights.

The 10 appealed the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decision and then filed a second suit to force Texas State University to grant them credit for the classwork they completed over the 1969-70 school year.

The school credit suit landed once again in the chamber of the U.S. Federal Court Western District and Judge Jack Roberts again ruled against the 10, stating that he could see no constitutional justification for countermanding the conclusion of the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

In 1972, the San Marcos 10 appeal was submitted to the U. S. Supreme Court, but only Justice William Douglas voted to review the case. The Supreme Court let the lower court’s rulings stand without rendering a decision on them.

The San Marcos 10 lost all credits earned during the 1969-70 school year and their official transcripts read “The U. S. Supreme Court has ruled for the administration and all credit is denied.”

College students all over Texas and around the nation continued to protest the Vietnam War, and the widely condemned Texas State University suspensions of the San Marcos 10 were quickly obscured.

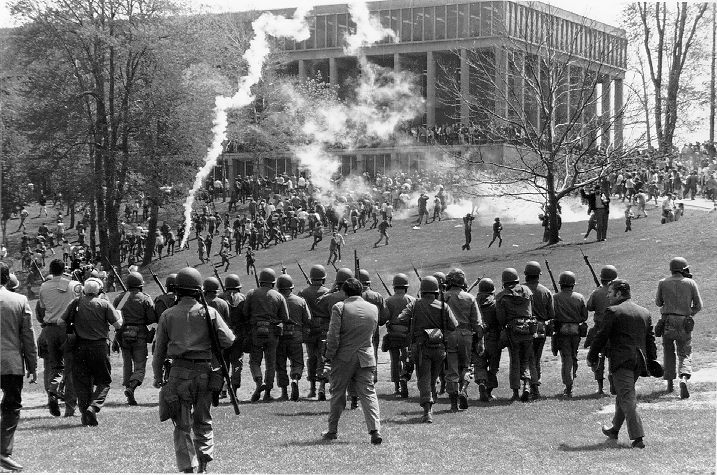

On May 4, 1970 — three days after President Richard Nixon referred to anti-war protesters at the nation’s colleges and universities as “bums” — the Ohio National Guard engaged a Kent State University demonstration in Kent, Ohio, and shot nine students, killing four and paralyzing one for life.

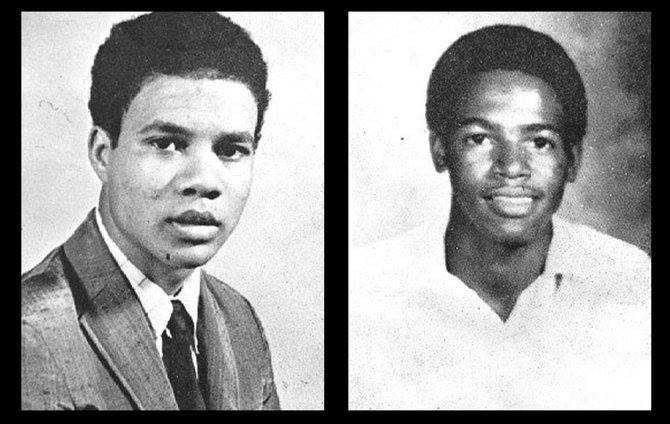

Eleven days later, in Jackson, Mississippi, city and state police shot fourteen anti-war demonstrators at Jackson State University, killing two.

Learn more from The San Marcos 10: An Antiwar Protest in Texas (History Press, 2019) by E.R. Bills.

This essay by E. R. Bills is excerpted from Texas Obscurities: Stories of the Peculiar, Exceptional & Nefarious. Bills also wrote the entry for the July 29, 1910: Slocum Massacre in Texas.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn