The Seizing Freedom podcast is an ideal resource to introduce students to the imaginative, defiant ways that Black people sought and enacted freedom throughout U.S. history — and brings to life voices that are often muted in textbooks.

The Seizing Freedom podcast is an ideal resource to introduce students to the imaginative, defiant ways that Black people sought and enacted freedom throughout U.S. history — and brings to life voices that are often muted in textbooks.

Produced and hosted by historian Kidada E. Williams, the show includes clips with professional actors reading letters and other documents by African Americans who freed themselves during the Civil War and built new lives during Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era.

One of Williams’ interviewees, Yale professor Crystal Feimster, adds, “Once you center a different set of people, it requires asking different kinds of questions. And it actually means we come up with different conclusions.”

To facilitate bringing this people’s history podcast to the classroom, we are sharing teaching ideas and resources for selected episodes. We begin with the one below by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca.

A Powerful Black Hand

Overview

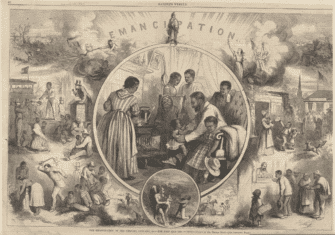

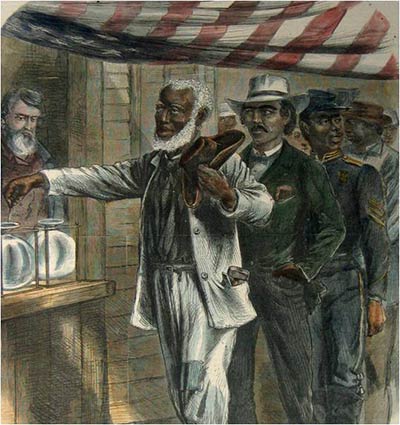

Black people, North and South, free and enslaved, were active agents in their own emancipation before, during, and after the Civil War. One site in which they were active was the U.S. military. In Frederick Douglass’s words, the war was begun, “in the interests of slavery on both sides. The South was fighting to take slavery out of the Union, and the North fighting to keep it in the Union . . . both despising the Negro, both insulting the Negro.” But through Black political and military mobilization, the war was transformed into one of emancipation.

The A Powerful Black Hand episode tells the story of the Black men and women who “shifted the tide of the war and opened new avenues for Black people to seize their freedom.”

Teaching Ideas

Historical Fiction

As students listen to the episode, ask them to think about which featured person they might want to do some imaginative writing about. Afterward, send students to the transcript of the episode to find the exact words of that person. Use that quotation as the basis for some writing.

Tell students, “Based on what you know and have learned, imagine what might have led to this moment and what might have happened afterward.” Students might write an interior monologue, poem, or short story to wrestle with the themes of the episode and what they’ve been learning about the struggle for emancipation.

Found Poem

As students listen to the episode, ask them to jot down phrases that they find poignant and/or moving. Afterward, students can gather more phrases from the transcript. Then, ask students to write a found poem made up of lines from the testimonies of people featured in the podcast. You might also ask students to create a found poem from lines and phrases from the document set above.

Teaching Documents

We offer suggested guiding questions for three sets of primary documents related to the themes in the episode.

Imagining a Just Response

Ask students to choose document 8, 9, or 10 (from the Teaching Documents list) to focus on for a writing activity. Each of these documents reflects a request made by Black soldiers to the U.S. government’s Freedmen’s Bureau. None of these documents includes a response from Bureau officials.

Ask students to write the response they believe this individual should have received from the Freedmen’s Bureau.

You might prompt students with some questions: What is owed to these veterans, most of whom were formerly enslaved people? And what is the U.S. government’s responsibility in making sure that debt is paid?

Key Quotations

Here are selected quotations from the episode, pulled from the transcript.

At the close of the war, and the start of Reconstruction, nearly 40 percent of Union forces occupying the former Confederacy were Black.

— Dr. Kidada E. Williams

I went to him [the commanding officer at Fort Monroe] and asked him to let me enlist, but he said it wasn’t a Black man’s war. I told him it would be a Black man’s war before they got through.

— Harry Jarvis, who had run away from the Virginia plantation on which he was enslaved

Frederick Douglass told Abe Lincoln, “Give the Black man guns and let him fight.’ And Abe Lincoln say, “If I give him a gun, when it comes to battle he might run.” And Frederick Douglass say, “Try him, and you’ll win the war.” And Abe said, “All right, I’ll try him.”

— Cornelius Gardner, a formerly enslaved soldier in Virginia

Two slaves belonging to . . . one of our nearest neighbors, had tried to escape to the Union soldiers, but were caught, brought back and hung. I never shall forget the horror of the scene — it was sickening. . . . This barbarous spectacle was for the purpose of showing the passing slaves what would be the fate of those caught in the attempt to escape . . .

— Louis Hughes who was enslaved in Virginia

I do really think that it’s God’s will that this war Shall not end till the Colored people get their rights. It goes very hard for the white people to think of it. But by God’s will and power they will have their rights, us that are living now may not live to see it. I shall die a trying for our rights so that others that are born hereafter may live and enjoy a happy life. If we can’t get our rights, we will die trying for them.

— Jacob Christy who enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment

I assisted in cleaning the guns and used to fire them off, to see if the cartridges were dry, before cleaning and reloading, each day. I learned to handle a musket very well, and could shoot straight and often hit the target. I thought this great fun. I was able to take a gun all apart and put it together again.

— Susie King Taylor, a formerly enslaved woman who worked for the First South Carolina Volunteers, the first Black regiment in the U.S. Army

My husband who is . . . now in the Macon Hospital at Portsmouth with a wound in his arm . . . has not received any pay since last May and then only thirteen dollars. . . . I have four children to support and I find this a great struggle. A hard life this! I, being a Colored woman, do not get any State pay. Yet my husband is fighting for the country.

— Rosanna Henson to Abraham Lincoln

In the first year of the war . . . the Black man begged the privilege of aiding his country in her need, to be . . . refused. And now he is in the War, and how has he conducted himself? . . . Obedient and patient and solid as a wall are they. Now your Excellency, we have done a Soldier’s duty. Why can’t we have a Soldier’s pay?

— James Henry Gooding, who enlisted in the Union Army one month after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, in 1863

Teaching Documents

The Freedmen and Southern Society Project website has made available selected documents from the multivolume Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861–1867. Drawn from the National Archives, the project is hosted by the history department of the University of Maryland in College Park.

The selections below are from Freedom: Black Military Experience.

Document Set One |

|

| Guiding Questions | Documents |

|

What racist barriers did Black soldiers face in the U.S. military during the Civil War? How did Black people (and their allies) organize and act to confront those barriers?

|

1. Affidavit of a Kentucky Black Soldier, March 29, 1865 Slaveowners (and local police and slave patrols) did everything they could to stop enslaved people from enlisting. A soldier recounted how he and his wife had been foiled in their first attempt to escape. 2. Commander of a North Carolina Black Regiment to the Commander of a Black Brigade, September 13, 1863 Colonel James C. Beecher, commander of a regiment of formerly enslaved men from North Carolina, wrote to his commanding officer to protest the recent tasks being assigned to Black troops. 3. Mother of a Northern Black Soldier to the President, July 31, 1863 Shortly after the battle of Fort Wagner, Hannah Johnson, the mother of a soldier in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, urged President Lincoln to guarantee the proper treatment of captured Black soldiers. 4. Soldiers of a Massachusetts Black Regiment to the President, July 16, 1864 Beginning in July 1863, Black soldiers in the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Infantry refused to accept unequal compensation with white soldiers. They petitioned President Lincoln to address the situation immediately. |

Document Set Two |

|

| Guiding Questions | Documents |

| Although some Black people found freedom in military service, they were often forced to leave behind families who were still enslaved. How did these separations affect the war for both soldiers and their families? |

5. Affidavit of a Kentucky Black Soldier, November 26, 1864 Threatened by their owner, the wife and children of Joseph Miller had accompanied him when he enlisted in the Union army. Miller described the ordeal that followed the expulsion of his family from the camp in which they took refuge. 6. Affidavit of a Kentucky Black Soldier’s Widow After Patsy Leach’s husband enlisted in the Union army in late 1864, the man who “owned” them, violently assaulted them. She fled with one of her children. 7. Statement by a Discharged Virginia Black Soldier, August 11, 1865 Attempting to reunite with his wife and children after his discharge from the Union army, John Berry confronted his former owner who refused to let him see his family. |

Document Set Three |

|

| Guiding Questions | Documents |

| As the war comes to an end, what do Black soldiers want from the U.S. government? What future are they advocating for? What threats do they face? |

8. Kentucky Black Sergeant to the Tennessee Freedmen’s Bureau Assistant Commissioner, October 8, 1865 In a letter to the Freedmen’s Bureau, Sergeant John Sweeny of Kentucky emphasized the importance of education to newly freed people. 9. Mississippi Black Soldier to the Freedmen’s Bureau Commissioner, December 16, 1865 Alarmed by Mississippi’s newly enacted Black Codes and by white supremacists’ violence against freedpeople, Private Calvin Holly wrote the Freedmen’s Bureau commissioner to describe conditions and propose a solution. 10. South Carolina Black Soldier to the Commander of the Department of South Carolina With the war over, the spokesman for soldiers in a South Carolina Black regiment asked his commander to allow the men to leave the service and return to their families, pursue purchasing land, and start their lives as free people. |

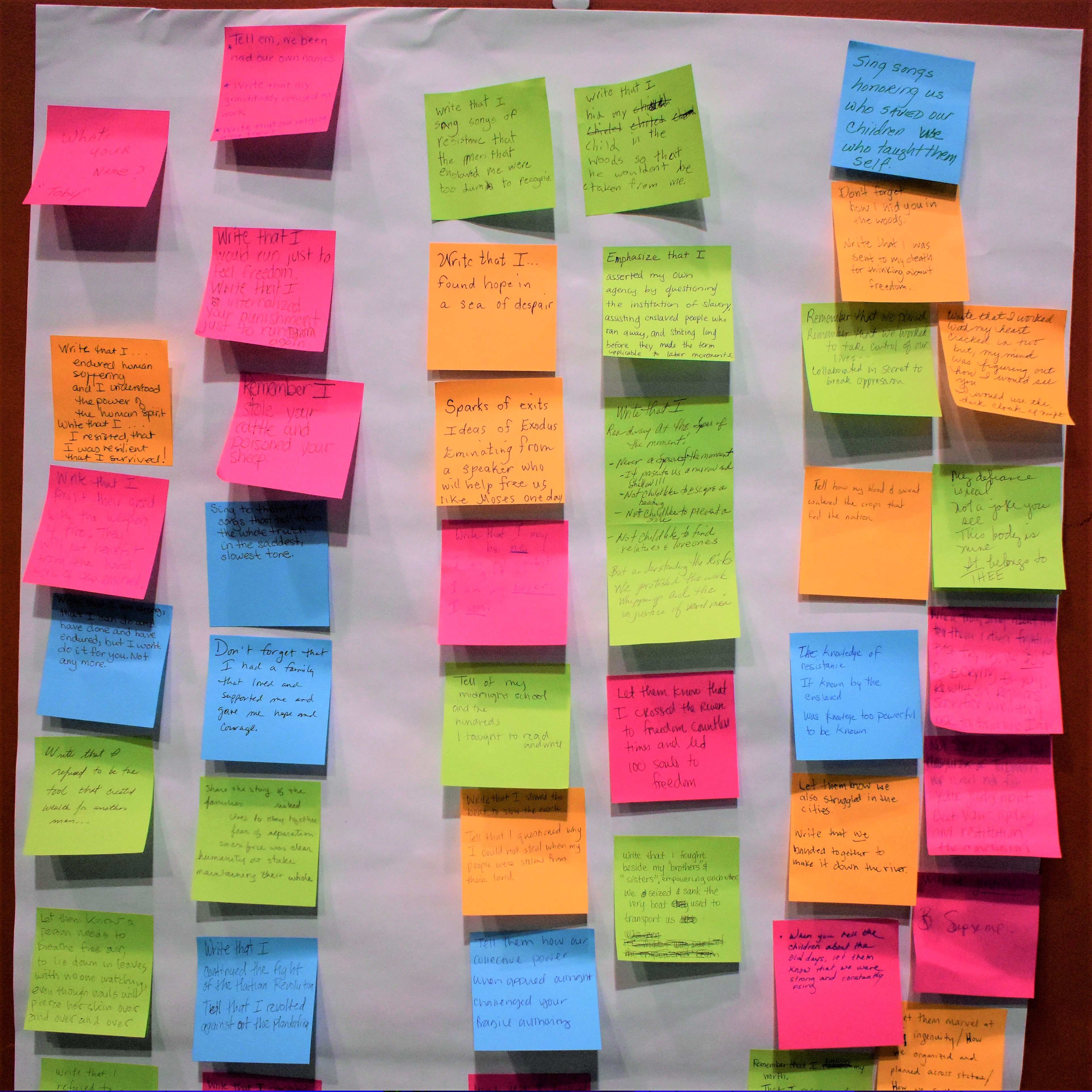

Classroom Story

I used the Teaching With Seizing Freedom Historical Fiction idea last year to wrap up the end of our semester. Students chose one of the historical fiction characters discussed in the podcasts and created a poem/short story using the transcripts. We typically spend some time setting up the assignment and discussing what it means to recreate a hypothetical scenario. Many students struggle with the idea of imagining what living in the Reconstruction era would have been like and have an even harder time conceptualizing what would have happened to people afterward. More often than not, students wanted to simply Google what happened to the figures and know instead of conjuring an ending for each.

This assignment is a great cross content task as it incorporates so many elements of ELA and Social Studies. By examining the quotes and having students create their own ending for someone, they are forced to reference facts, include explanations, and synthesize ideas. Giving the students some agency in the hypothetical lives of people who themselves often struggled to gain agency makes it all that more impactful when students learn more about their figures. Some of them are excited when they tend to be right while others are shocked by what really happened next (of course not everyone is easy to research and in some cases we cannot find definitive answers).

Seizing Freedom helps history to come alive and makes a meaningful impact on students in a way that few other lessons can. The combination of podcasts and transcripts appeals to many different learning types and allows for multiple forms of information processing. Teaching Reconstruction is incomplete without this work.

Share YOUR Teaching Stories

We’d love to hear how you use this lesson or any of the other Seizing Freedom episodes in your classroom. Share your teaching story and we’ll send you a copy of Kidada E. Williams’ book, They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I.

We’d love to hear how you use this lesson or any of the other Seizing Freedom episodes in your classroom. Share your teaching story and we’ll send you a copy of Kidada E. Williams’ book, They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I.

Learn More

Find related readings and teaching resources below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn