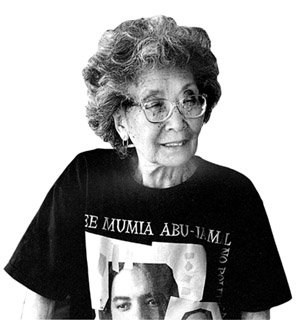

Yuri Kochiyama speaks at an anti-war demonstration in New York City’s Central Park around 1968. Courtesy of the Kochiyama family/UCLA Asian American Studies Center.

Yuri Kochiyama (May 19, 1921 – June 1, 2014) was a tireless political activist who dedicated her life to contributing to social change through her participation in social justice and human rights movements.

She was born and raised in San Pedro, California. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, her father, just out of surgery, was arrested and detained in a hospital. “He was the only Japanese in that hospital,” Kochiyama recalls, “so they hung a sheet around him that said, ‘Prisoner of War.’” He died shortly thereafter.

In 1943, under President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, Kochiyama and her family were sent to a concentration camp in Jerome, Arkansas, for two years. This experience and her father’s death made Kochiyama highly aware of governmental abuses and would forever bond her to those engaged in political struggles. After being released, she moved to New York and married Bill Kochiyama, veteran of the all-Japanese American 442nd combat unit of the U.S. Army.

Kochiyama’s activism started in Harlem in the early 1960s, where she participated in the Asian American, Black, and Third World movements for civil and human rights, ethnic studies, and against the war in Vietnam. She was a fixture in support movements involving organizations such as the Young Lords and the Harlem Community for Self Defense. As founder of Asian Americans for Action, she also sought to build a more political Asian American movement that would link itself to the struggle for Black liberation. “Racism has placed all ethnic peoples in similar positions of oppression poverty and marginalization.”

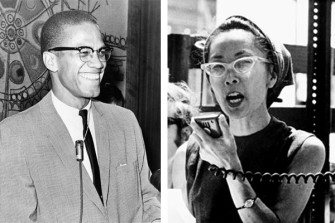

Malcolm X and Yuri Kochiyama

In 1963, she met Malcolm X. Their friendship and political alliance changed her life and outlook. She joined his group, the Organization for Afro-American Unity, to work for racial justice and human rights.

As Vincent Intondi explains in an article about organizing against nuclear weapons:

On June 6, 1964, three Japanese writers and a group of hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors) arrived in Harlem as part of the Hiroshima/Nagasaki World Peace Study Mission. Their mission: to speak out against nuclear proliferation.

Yuri Kochiyama, a Japanese American activist, organized a reception for the hibakusha at her home in the Harlem Manhattanville Housing Projects, with her friend Malcolm X.

Malcolm said, “You have been scarred by the atom bomb. You just saw that we have also been scarred. The bomb that hit us was racism.” He went on to discuss his years in prison, education, and Asian history. Turning to Vietnam, Malcolm said, “If America sends troops to Vietnam, you progressives should protest.” He argued that “the struggle of Vietnam is the struggle of the whole Third World: the struggle against colonialism, neocolonialism, and imperialism.” Malcolm X, like so many before him, consistently connected colonialism, peace, and the Black freedom struggle.

Yuri was present on the day Malcolm X was tragically shot and killed in 1965. In the Life magazine article “Death of Malcolm X,” she can be seen crouched in the background, cradling Malcolm X’s head.

In the 1980s, Kochiyama worked in the redress and reparations movement for Japanese-Americans along with her husband Bill. Support for political prisoners — African American, Puerto Rican, Native American, Asian American, and progressive whites — was been a consistent thread in her work.

When Yuri died on June 1, 2014, Lehman College assistant history professor Robyn Spencer wrote:

I hope  that remembrances of Yuri Kochiyama don’t start and end with the snapshot of her caretaking Malcolm X in his last moments, just like the tributes that reduced Rev. Vincent Harding to only being Dr. Martin Luther King’s speechwriter.

that remembrances of Yuri Kochiyama don’t start and end with the snapshot of her caretaking Malcolm X in his last moments, just like the tributes that reduced Rev. Vincent Harding to only being Dr. Martin Luther King’s speechwriter.

It compounds the tragedy when people, who represent the grassroots and plural nature of the 60s movement, are reduced upon death to their relationship with Great Men.

What I will remember about Yuri Kochiyama is her careful attention to mentoring and cultivating relationships. The salons she held in her apartment were influential to so many. They are mentioned in several books. She also dutifully collected and saved things.

Kochiyama came to the 1995 round-table on African American liberation movement leader Mae Mallory with a scrapbook full of memories, newspaper articles and the like. I have come across many of her handwritten letters in different archives.

It is a little known fact, for example, that in 1977,

Kochiyama joined the group of Puerto Ricans that took over the Statue of Liberty to draw attention to the struggle for Puerto Rican independence.

Kochiyama bridged people and movements, a true human rights activist.

Watch this remembrance clip from Asian Americans Advancing Justice.

This profile was adapted from various sources, including Asian American Women of Hope: Study Guide (1199 Bread and Roses Cultural Project, 1998).

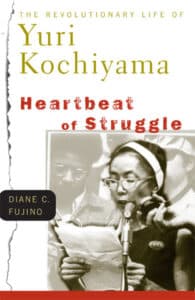

Learn more about Kochiyama in her memoir Passing It On, the biography Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama, the film Passion for Justice, and Yuri Kochiyama Solidarity Project website. There are additional resources below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn