On April 3, 1969, as he sat in his courtroom in front of a feverish assembly of cameras, lights, and reporters, Judge George Crockett Jr. addressed a city that had been overwhelmed with racial tensions for four days.

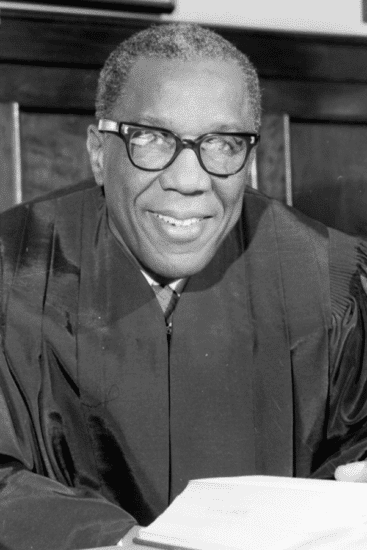

Judge George Crockett Jr. Courtesy of the Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University.

One white officer had been shot and killed, and to those who sought a hasty response from the courts, Crockett had a clear message:

Because a terrible crime was committed, it does not follow that other wrongs be permitted or condoned. Indeed, constitutional safeguards are needed even more urgently in times of tension than in ordinary times.

News outlets, including many represented by the very individuals in front of him, had “use[d] this tragic affair to intensify community hostilities which are already so deep and divisive.” He reminded journalists of their awesome power to report on “the real dangers to our community” by “concentrate[ing] on the underlying causes of crime and social disorder. The causes are steeped in racism,” he intoned, “racism in our courts, in our jails, in our streets and in our hearts.”

Thusly, did Judge Crockett respond to an event that the Detroit community would come to know as the New Bethel Shoot-In.

On the night of March 29, 1969, the Republic of New Africa (later, Republic of New Afrika) was holding a one year anniversary celebration at the New Bethel Baptist Church in Detroit when a shootout took place between two white rookie police officers and armed RNA members outside of the church. One officer, Michael Czapski, was fatally shot while the other called for backup.

More Detroit police quickly arrived at the scene and shot indiscriminately into the church before arresting all 142 men, women, and children inside the church. They detained the RNA members for hours in a precinct parking garage, refusing them telephone calls. A number of them had suffered injuries due to police gunfire.

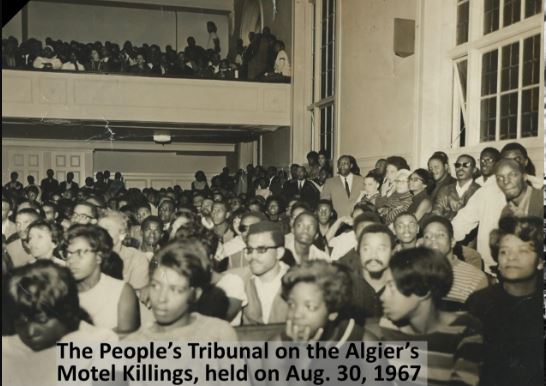

Word of what was happening got to Recorders Court (Detroit’s criminal court) judge George Crockett Jr., who, in the early morning hours on March 30, headed directly for the police station. He discovered that police still had not brought charges against any of the people they were holding, though they’d run nitrate tests and held the RNA members incommunicado. Concerned that the constitutional rights of Black Detroiters were being railroaded, there in the station, in an unused room, he set up an ad-hoc courtroom and began habeas corpus proceedings.

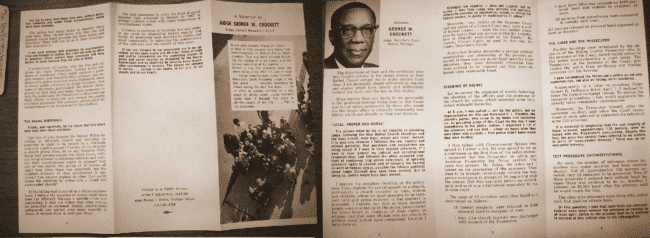

Pamphlet with Judge Crockett’s statement, published by the Detroit Industrial Mission in April 1969. Courtesy of the Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University.

Throughout the morning and into the afternoon, police and prosecutors released 130 individuals against whom they had no evidence — indeed, they were likely arrested illegally. Wayne County Prosecutor William Cahalan wanted nine of the remaining individuals to be detained as “key suspects,” including some whose nitrate tests produced positive results.

But Crockett refused and ordered their release because, he argued, the nitrate tests had been unconstitutional. Indeed, denying counsel to all those arrested, let alone conducting nitrate tests, violated the Supreme Court’s recent Miranda ruling, he asserted. That decision showed that it was vital “to stop police from running roughshod over the rights of the accused.”

Immediately, conservative forces including the Prosecutor’s office, the Detroit Police Officers Association, the Detroit News and some elected officials mounted a campaign against Crockett. “Police Fear Crockett Ruined Hunt for Killer” blasted the front page of the Detroit News. Off-duty officers and their families picketed outside the Recorder’s Court building with signs that read, “Crockett Justice? Release killers. Prosecute prosecutors. Give license to kill policemen.”

They called for investigations into Crockett and for his removal from the bench. Anti-Crockett forces were aided by white moderates and liberals who, likewise, took Detroit police at their word when they claimed the RNA opened fire first, not the police, and in assuming that the role of judges was to support the police.

This wasn’t the first time Crockett had been targeted for vitriol and attack because he stood up for the rights of unpopular defendants. He was the only Black attorney to defend Communist Party leaders in the Foley Square Trial in 1948, and that left him ostracized amongst his Detroit community and serving a four-month prison stint (along with the other defense attorneys on the case) for contempt of court.

Undeterred, Crockett went on to represent Black radicals in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee, including future mayor Coleman Young. It became Crockett’s life mission to pursue equal justice and civil liberties protections for the least protected and economically comfortable defendants.

Doing so in March of 1969, with almost 150 RNA members, showed the high cost of such courage. For a few days after the habeas corpus proceedings, Judge Crockett stayed quiet — in no small part because threats against his life mounted and he had to be put under police protection (which would be necessary for months). But four days after the habeas corpus proceedings, on April 3, 1969, he broke his silence with a powerful press statement. He corrected the numerous false accounts that had appeared in the white press, going over the facts of that day and stressing the point that it had been prosecutors who had moved to release the vast majority of those detained.

Most importantly, Crockett’s statement was an unswerving defense on the rights of marginalized defendants and the ways that judges maintained racism and classism through the courts. In short, he called out a Jim Crow judiciary and showed how its basic tenets could be seen through the New Bethel shoot-in and its aftermath.

On the question of prosecutor Cahalan’s request to detain several men on grounds of positive nitrate tests, Crockett centered the importance of constitutional rights:

I am most anxious that criminals be apprehended, tried and brought to justice. But I will not lend my office to practices which subvert legal processes and deny justice to some because they are poor or Black.

His actions in releasing the defendants were “legal, proper and moral” but, because judges and prosecutors had railroaded the rights of Black and poor defendants for so long, the public thought it was Crockett who had erred:

Indeed, it is precisely because I followed the law, equally and without partiality, that questions and accusations are being raised. . . . An angry prosecutor [Cahalan], lacking police evidence or testimony which might produce a probable suspect, and resentful that ordinary and undemocratic police practices were challenged, chose to divert public attention to Judge Crockett. And some of the media, particularly the Detroit News, picked up the lead and began their campaign to help the police and the Prosecutor’s office continue their efforts to dominate and control the courts.

Crockett concluded by reminding his audience of the double standard by which constitutional rights were applied:

Can you imagine the Detroit Police invading an all-white church and rounding up everyone in sight to be bussed to a wholesale lockup in a police garage? . . . Can anyone explain in other than racist terms the shooting by police into a closed and surrounded church? If the killing had occurred in a white neighborhood, I believe the sequence of events would have been far different.

In the end, Crockett’s actions were widely, if not always enthusiastically, proclaimed legal and appropriate — by the National Lawyer’s Guild, New Detroit Inc.’s Law Committee, and the Michigan Judicial Tenure Commission. As further vindication, Detroit voters kept returning Crockett to the bench until his retirement in 1978.

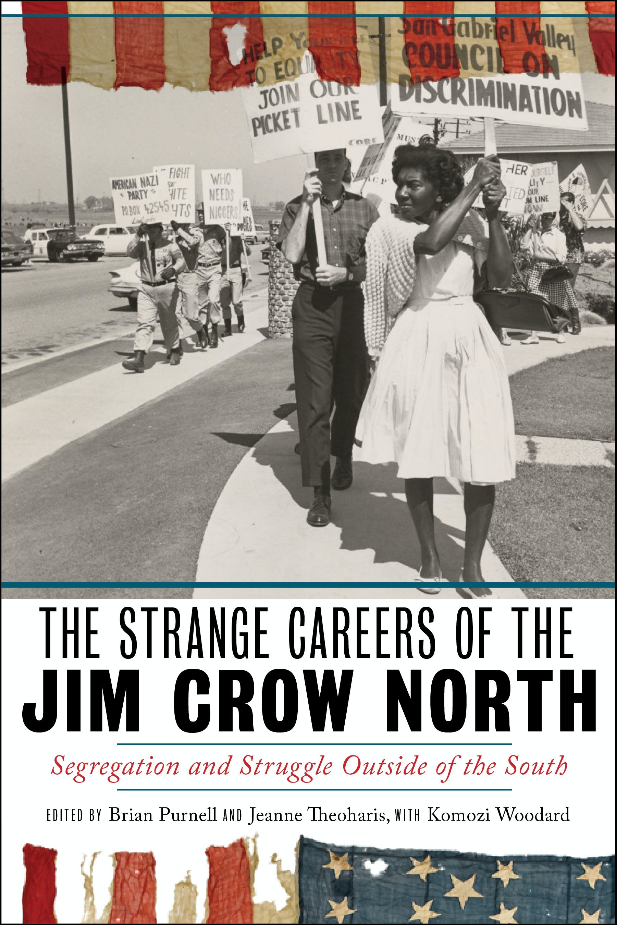

This entry in our This Day in History series is by Say Burgin, an assistant professor of history at Dickinson College, where she researches and teaches 20th-century African American and social movement history. She wrote an essay on Judge George Crockett Jr. and the New Bethel Shoot-In for The Strange Careers of the Jim Crow North: Segregation and Struggle Outside the South (eds. Brian Purnell and Jeanne Theoharis, with Komozi Woodard). She co-created an educational website on Rosa Parks. Twitter @sayburgin

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn