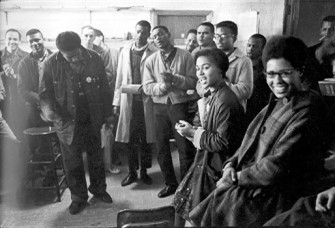

Courtland Cox and Judy Richardson, January 2020. Credit: Sharon Farmer/sfphotoworks

By Katie Orr

On Friday, May 15, veterans of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) visited the virtual classroom of California teacher Evan Bartz and his 6th-grade students. Judy Richardson and Courtland Cox spent an hour with the students, talking about their formative years in SNCC and its relevance today.

This visit was part of a unit on SNCC for Bartz and his students, who live in the San Francisco area. Several weeks earlier, Bartz had attended a Zinn Education Project People’s Historians Online mini-class with Richardson and Cox, who talked about SNCC to an audience largely made up of teachers. Bartz invited the speakers to his class so that his students could learn from them first-hand. (Learn more about the People’s Historians Online series.)

Before the classroom visit, the students watched Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot and worked on group research projects. They also used the Zinn Education Project lesson, Teaching SNCC: The Organization at the Heart of the Civil Rights Revolution, by Adam Sanchez. During the visit, students asked questions and presented some of their own research about SNCC.

The live video lesson began with Richardson telling a story about a dramatic day working with SNCC in Mississippi. The students watched on their individual screens, respectful and curious.

Richardson described how in July 1964, while working at the SNCC headquarters in Greenwood, June Johnson, a local 16-year-old SNCC worker, who had been beaten with Fannie Lou Hamer in a Winona, Miss. jail, ran in to tell her that Silas McGhee was in the hospital. He had been attacked after sitting on the “white” side of the local movie theater. McGhee was from a strong Movement family in Greenwood. His mother, Laura McGhee, had used her farm to secure bail for Movement workers and was known to defend herself and her family against the police and other racists.

Richardson drove with June to the hospital where they had to avoid a small white mob gathered outside the segregated hospital in order to enter the building. FBI agents were present but unwilling to intervene on McGhee’s behalf. Richardson told the students that she was angry that the FBI refused to help, but she was not helpless: She had dimes.

All movement workers had to have dimes with them in case they needed to make an emergency call on a public phone (no cell phones then). She called the SNCC office, the U.S. Justice Department, and SNCC’s national Friends of SNCC network. Calls coming in from all over the country would alert the local sheriff that he was being watched. Movement workers didn’t have cell phones, but they did have dimes!

June returned from checking on Silas and told her that he would be all right and that his mother and older brother, a paratrooper then on leave, were with Silas. Eventually, her calls and those of the SNCC network pressured the U.S. Attorney General’s office to order the sheriff to protect McGhee while moving him to a hospital in Jackson, and to escort Richardson back to the SNCC office.

Courtland Cox picked up the thread. He described the context in which this happened and the history of “separate but equal” laws. He told Bartz’s students what it was like to live through the conditions of segregation that McGhee had been protesting. They gazed intently as Cox described how he became aware of politics and formed his sense of right and wrong. It was when he was about their age and he heard about the murder of Emmett Till and the courage of the Little Rock Nine.

Even though I couldn’t do anything when I was 13 or 14 years old, I was building my consciousness at that time. And what you’re learning and thinking about today will be what will stay with you for the rest of your life. The political values I developed in my teens are the same values I have today.

When he finished, the students asked questions.

One student asked, “What were your intentions when you were protesting? What were you trying to solve?”

Richardson explained it was a sense of righteous rage that drove her activism. She said, “You don’t have a right to deny me. You don’t get to do this! It’s not right.”

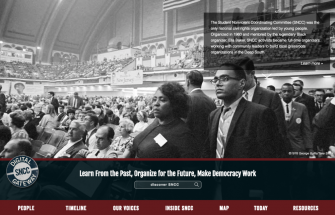

Learn more at the SNCC Digital Gateway (click image) and CRMvet.org.

Another 6th-grader wanted to know what was the hardest part of working in the Movement.

Cox reflected on when he was in the South, living with people in extreme poverty:

We were there trying to do a number of things for democracy and desegregation, but the economic exploitation of the people weighed on them and weighed on me. And how did we overcome that heaviness? How do we overcome it today? It seemed to me that continuing to organize, continuing to make sure that those people and their kids would be in a better place, is how we overcome the fear.

The last question was about hatred and the role it plays in injustice today.

Richardson said racist violence isn’t so much a matter of hatred, but a resistance to sharing power and a fear by some that they will lose their power.

Cox said he does not think hatred is the driving force that creates the problems he wants to solve. Selfishness is. In order for people to accumulate and maintain wealth, they create dysfunctions in communities. He lamented:

It’s like the exploitation of workers during COVID today. Selfishness of rich people who make money off the factories or want the meat that comes from them, they don’t care whether these people live or die as long as they continue to make money.

Students presented research on the choices SNCC faced in the 1960s.

Students presented what they had learned about the choices SNCC faced in the 1960s.

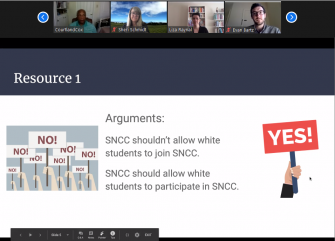

A small group of students presented a slideshow to share their research about a tactical question SNCC organizers faced in the 1960s (prompts from the Zinn Education Project SNCC lesson). Students had debated the question, “Should SNCC allow 1,000 white students to join SNCC down in Mississippi? If yes, should their roles be limited?”

The small group members took turns discussing the pros and cons of bringing more white people into the Movement. They talked about the SNCC leaders and their activist philosophies that guided how they grappled with this question. (Offline, other student groups had debated two additional questions: “Should SNCC focus its efforts on voter registration or direct action?” and “Should SNCC workers carry guns? If not, should SNCC allow or seek out local people to defend its organizers with guns?”)

After the presentation and discussions, another teacher observing the class asked Richardson and Cox why they agreed to visit with Bartz’s students.

After the presentation and discussions, another teacher observing the class asked Richardson and Cox why they agreed to visit with Bartz’s students.

“I think we owe it to the young people,” Cox said. “Our elders did the same thing for us. We’d be nothing if there wasn’t a whole group of people who shared with us. What we did was necessary but not sufficient. It’s important for us that we get young people to do, in their time and their space, what is necessary. What’s necessary. Even if they can’t do it all.”

Richardson nodded. “If you do nothing, nothing changes. We heard that over and over again from the older activists who guided and guarded us.”

Student Reflections

Bartz asked his students to send him their thoughts about the SNCC presentation and what they thought about meeting people who were part of civil rights history. Here are some of their responses.

What did you appreciate about the SNCC veterans’ visit?

I appreciated that they were very truthful with us, and they told us their true feelings. I appreciated that they were very honest about what happened.

I appreciated that they took the time to visit us and listen to us. I think they helped us improve and get a real feeling of how it was like to live back then, something I don’t think you can get from reading an article or looking at a photo. I also appreciate how they treated us like adults, not little kids.

What surprised you about their stories, responses to your questions, or feedback?

I was surprised at how brave they were, doing the things they were doing. You could tell that they were still angry at the injustice back then, still fighting, but also still sharing funny or happy memories of that time as well. I was surprised that they could see all the good in that horrible time.

It surprised me how there were actual people behind this and it is not just a story that we read about, also how scary it was for them and how it must have felt impossible to make any progress.

What surprised me about all their stories was how strong they were, because they were young when they stepped up to protest, went to jail for no reason, and saw many of their friends die next to them. I think that it’s amazing that they’re willing to tell the stories and sort of reliving that experience.

What is something you know now that you didn’t know before their visit?

I did not recognize how involved the students were in the movement. I had thought that they were part of it, but when I heard Judy and Courtland sharing stories from when they were in 8th and 9th grade, I realized how the movement was really made possible by the students, and that was very inspirational.

I now know about how teenagers and children were braver and knew how to stand up for themselves than adults in the FBI (from Judy’s story).

I didn’t really know how many people died and how many loved ones and friends went to jail, but most of all, I didn’t really understand what it meant to protest at such a young age where you could get beaten up or gone to jail for standing up.

We cannot measure the longterm effects of Courtland Cox and Judy Richardson’s engagement with young people and educators, but we know that interactions between young people and veterans of the Civil Rights Movement can forge new links in a chain of activism and struggle for justice that goes back centuries.

Bartz’s class was not recorded, however a similar presentation by Courtland Cox and Judy Richardson during the People’s Historians Online class on April 24, 2020 is available to stream.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn