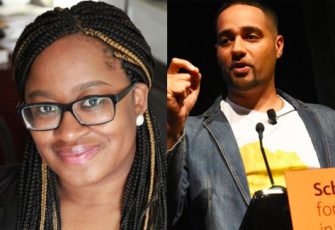

On June 5, the weekly People’s Historians Online session addressed the nation-wide rebellion against police violence with a conversation between Keisha N. Blain and Jesse Hagopian.

On June 5, the weekly People’s Historians Online session addressed the nation-wide rebellion against police violence with a conversation between Keisha N. Blain and Jesse Hagopian.

During the session, Blain and Hagopian addressed the role of police throughout U.S. history, the connection between lynching and police brutality, and the importance of highlighting stories of resistance, particularly by women of color in the fight for human rights. Here are just a few reflections from participants on what they learned. (More reflections at the end of this page.)

I have never thought about “policing” as having a history. I know that sounds weird, but it never occurred to me to look at the history of law enforcement in the United States in order to understand this 2020 uprising. I will absolutely begin this study right away!

I appreciated all the teaching resources provided; I look forward to using them in my future classroom, and I take seriously the charge to reframe the telling of history with people of color as agents of change, not just victims of oppression.

The important absolutely necessary reminder that there is always resistance in play and to always balance the oppressive content with the resistance; and the history of policing, and connecting that to militarism in the United States since the founding of the nation with the genocide of Indigenous nations.

The origins of the police related to slave patrols. I will work to incorporate this long history into how I teach about police brutality toward Black people.

When Dr. Blain mentioned the “mothers of the movement” I immediately thought of Trayvon Martin’s mother . . . but she talked about the mothers of Eleanor Bumpers and Perry . . . stories from the ’80s. This was a reminder to me that understanding the depth of our organizing around policing is important, and that our organizing can be seen in every era, every decade.

One thing that stood out to me is the key leadership of women in social movements, especially the women in the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA), which I had not heard about before. I want to incorporate more Black women’s voices when I teach about the Civil Rights Movement and resistance to oppression. I am excited to explore the Ida B. Wells resources that were shared too.

Below, find highlights of the session, a full video recording, recommended resources, and participant feedback.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: I can’t tell you how excited I am to have this discussion about the rebellion that’s sweeping the country right now and look at the historical roots of it, and where it might go and what we need to demand. I’m just so thrilled to be in conversation today with Dr. Keisha Blain.

I’m very excited to get this rolling, but before we do, I just want to say some words about how today is going to work. Some of you are joining us for the first time and some of you have participated in one or each of our sessions over the last five weeks. I’m so honored to get to help host this series. It’s incredible that professor Jeanne Theoharis helped to launch this whole series of people’s history lessons.

I’m a high school teacher here in Seattle, and I’m an editor with Rethinking Schools, which coordinates the Zinn Education Project along with Teaching for Change. The Zinn Education Project is hosting this session today, and it offers the free downloadable lesson plans that many of you have probably used in your middle and high school classrooms from the Zinn Education Project website. I highly recommend you go to the website and find lessons that relate to the things that you’re teaching. In particular, we offer a lot of lessons that address the themes of this session here today on the roots of the rebellion. We have lessons on Reconstruction, on the Tulsa Massacre, on redlining. on Reparations, on the fight for voting rights, and really so much more. Sp check out all the teaching materials; they’ve made my classroom so much stronger, my pedagogy so much more relevant to my kids’ lives, as well.

Before I begin my conversation with Dr. Keisha N. Blain, we want to find out who is in the room and go through our plans for our time together. We are going to do a quick poll to find out how many teachers, librarians, teacher educators, historians, parents, students, labor or community organizers, educators of all kinds, are in the room with us. Many of you have multiple roles, so just pick the primary role that you have.

Throughout the session, we want you to use the chat box to post questions, comments, and resources, if you have ideas related to the topics we’re talking about. Then our guest speaker will read your questions and we can try to get to them after the breakout groups. Then we’ll do a short evaluation at the end. So, here we’re seeing the results of the polls. So, 55% of us on the Zoom call today are educators, 10% students — yay for the young people who are leading the rebellion — we have 1% librarians, 1% teacher educators, 13% historians, 7% labor or community organizers, and other 10%. Thank you all for being with us today.

We’re now ready to start our conversation. After about 20 minutes, we’ll pause so that you can meet each other in small groups. It’s a really important opportunity we have with these calls to break into small classrooms and discuss the issues that we talked about. Then you get to come back at the end and ask any questions. So, I’m really happy to introduce you all today to Dr. Keisha N. Blain, an award-winning historian of the 20th century United States, associate professor, and so much more. Definitely get the book Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom. I highly recommend folks check out her work. If you haven’t seen some of her recent articles, as well, in the Washington Post, you have to check them out. She is also associate professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh, the president of the African American Intellectual History Society. And Blaine is the author of the book that you just just saw on the screen. So, we’re going to have a rich dialogue about this rebellion that is happening in the streets near you and where it really came from. So, welcome.

Keisha Blain: Thank you so much for having me. It’s wonderful to be here together. I know we’re all in different places and different spaces, but it certainly feels like a community. And it’s good that we have this opportunity to have a conversation. As Jesse noted, if you do you have questions and comments, please indicate those questions and comments in the chat box and I’ll try my best to follow along. I’m really just hoping that I can offer some insights and resources for all of you. But I do see this as a conversation, so if you ever have an idea or thought, something that I’ve said that makes you think of something else that you have found effective in the classroom, please do share. And hopefully we can share it, we can get all this information out to everyone on the call, via the website, afterward. So, thank you for having me.

Hagopian: It’s really an honor to be in dialogue with you today, to welcome you to this community. What I love about this community is that it reaches so many more people, all the educators in this meeting, who then go and share this information with students. We’re really transforming classrooms and schools around the country. We’re really lucky to get to learn from your research and insights, and I just want to start by saying that there have been so many low moments for me, some moments of deep trauma really, for me and for millions of others around the world, as we learned of the deaths of George Floyd, of Breonna Taylor, of Ahmaud Arbery, and so many others in our own local communities that people have never heard of.

But, I have to say also that today my heart is really just singing. I think after having been in the streets with so many young people yesterday who were chanting “Defund the police,” they were just absolutely determined. You could see it on their faces; they knew they were going to win in this struggle against police violence and institutional racism. And the size and scope of this rebellion is just truly breathtaking. So, I wonder if you have a favorite moment or a sign or a speech from the uprisings around the globe in the last few days, and how would you compare this uprising to others throughout history?

Blain: One of the things that caught my attention in the last few days has been people sharing videos from different parts of the globe. One video caught my attention in particular, and that was a group of activists walking through Trafalgar Square in London. I stopped for a moment and looked at it and immediately thought about my own work and the work that I’ve done in Set the World on Fire. In chapter five, I briefly describe a scene of Amy Ashwood Garvey, who, at the time, was living in London. She got together with several other Black activists, revolutionary Black activists, in 1935, and they were marching through the same square, and they were calling out colonialism.

And of course, as you know, those who teach world history immediately know the significance of 1935 for so many, so many things. But in particular, in 1935, Italy invaded Ethiopia, and that’s the moment where people across the Black diaspora are coming together, in a similar vein as we’re coming together now, and denouncing colonialism, denouncing white supremacy, and saying this is terrible, this needs to stop, and also extending a hand of support and solidarity to the Ethiopians. So it was great then to see a video circulating, and it just brought me right back to that scene that I talked about in chapter five. Perhaps in that image, in and of itself, that might speak to the possibilities of where this movement, I think, will be headed.

I think we’re certainly seeing uprisings across the country, and I think we’ll see more and more uprisings, more and more people standing up in solidarity with the struggle for freedom in United States. We’ll see that taking place, we’ll see people standing up in support in various parts of the globe. And that’s key, because if we’re not careful, we fall into a trap of imagining that racism or white supremacy is an American problem in America and an American problem alone. But certainly we know better; we understand that it is a global issue. So we have to think of ways to tackle it globally.

The other thing, too, in looking at what’s taking place today, immediately, I think about the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. It’s tough because I certainly don’t want to suggest that every single thing that’s happening today is the same. I think that the question is really about the threads, the similarities, the commonalities that we see, whether it’s even just thematically the topic of civil rights. I keep trying to reiterate the point to everyone that when we talk about police violence in the United States today, it is not divorced from a conversation of civil rights in the United States. It certainly is very much a part of the discussion, it has to be. How can you have citizenship rights, how can you have civil rights, political rights, or even human rights, if you can’t, as a Black person, walk the streets freely? If you’re going to have an encounter with the police that could potentially lead to your death, to your killing? So all of these things are connected. And I think I reflect on the 1960s and 1970s, because, in a similar way, people just came together collectively outraged by what was going on and trying to figure out ways to work together to bring about the changes they wanted to see.

Hagopian: No doubt. I think a lot of the educators that are in this forum with us right now have been talking to their students about these issues for some time. I’m just curious about the folks who are with us. I wonder how many of you have been teaching for Black lives, and/or are recommitting to doing so? So, we have a poll that just went up, and I’m curious about the results. Check as many as apply to you. So, please fill out this poll as we continue the discussion.

I want to share with you one of my favorite moments from this rebellion in the last few days, if that’s all right. It was when Women’s March organizer and activist Tamika Mallory told protesters in Minneapolis at one of the large rallies there, she said, quote,

America has looted Black people. America has looted the Native Americans when they first came here. Looting is what you do. We learned it from you. We learned violence from you. If you want us to do better then, dammit, you do better.

And that really struck me. I think her statement was just so powerful, and it went viral around the world. I’m wondering if you could talk more about the significance of Black women leaders in this movement today and throughout history?

Blain: Absolutely. I think and I remember seeing that video too, just circulating on social media. There was a just powerful moment to see Tamika Mallory speaking before crowds of people, and it brought me back to different moments in history, and not only moments where women are standing in front of large audiences, but also moments where women are doing the work, sometimes quietly, quote unquote, “behind the scenes,” out of the purview of the spotlight.

I think immediately if someone like Ida B. Wells. Ida B. Wells was someone who, of course, everyone knows about Ida B. Wells. We talked about how Ida B. Wells, even recently, was just honored with a Pulitzer Prize citation. We lift up Ida B. Wells as someone who worked tirelessly to challenge lynching in the United States, an anti-lynching crusader who worked not only within the U.S. context, but also globally. I also think it’s important to emphasize. Ironically, I started off talking about London and here I am bringing up the UK again, because Ida B. Wells traveled to the UK in the late 19th century to talk about lynching, to forge collaborations with people there, to figure out strategies to bring an end to it.

And Ida B. Wells was someone who, in the moment in which she was doing the work that she was doing, she wasn’t always well received. I mean, the reality is, as we know, she had to flee Memphis because white folks were trying to lynch her. They were trying to kill her for shedding light on the very issue that she was writing about. And this is someone who was just toiling for many years and wrote extensively.

And, of course, we’re talking about teaching. One of the things that I would encourage you to do, if you’re not already doing it, is think about ways that you can draw upon the writings of Ida B. Wells. The Red Record, which she published, is now easily available on the internet. Depending on the grade that you teach, you might pull parts and pieces of The Red Record. Have students read that in conjunction with some contemporary pieces, maybe op-eds from today. The recent op-ed that I wrote draws a link to lynching, but I’m certainly not the only one to do that. You can look at Isabel Wilkerson’s earlier piece, I think in 2015, that draws a parallel to lynching and police violence. You can use these kinds of texts get students to start thinking critically and to ask questions. Some people are resistant to calling police killings ‘lynchings’ and they’re resistant to it because they think that it’s not a good practice within the history, because lynchings are uniquely described as a public spectacle. There are all these facets of it, and I personally don’t get caught up in those sorts of little things. I think that, ultimately, police killings function the exact same way. So, in the end, why dance around the issue? It’s a lynching; it was a lynching then and it’s a lynching now. Maybe we’ve shifted from ordinary citizens to police officers, but in the end the result is the same, and it is still very public.

Hagopian: And sometimes they do make a public spectacle too, especially when they leave the bodies in the streets for a long time.

Blain: We saw that, if I’m not mistaken, this week. Just a few days ago, there was an incident of someone killed by the police, and I believe they were laying in the street for probably 12 hours. So that’s why I’m always saying to people, you get caught up in the terminology, but the reality is, it’s state sanctioned violence and police killings. But it’s in this context, and previously, it was killings from individuals, but even sometimes the police then, too. So, it’s important to draw those connections for students.

Back to your question about women’s leadership. Ida B. Wells was a great person to emphasize in this moment. I would also throw out someone like Fannie Lou Hamer, who was someone I have found such inspiration from. I am writing a book on humor now, so I’m just consumed with her writings, and I just can’t get enough of Hamer. And I won’t stop talking about her for a while. But Hamer spoke openly about police violence and brutality, too. That’s something that I think we don’t often emphasize. So, if you’re teaching, you want to pull those narratives. And you can look at the 1964 speech she gave before the DNC, I believe. There’s actually a very good collection of essays on Fannie Lou Hamer speeches. You could pull from there, you could just get the transcript and get people to read it, get your students to engage the speech, and maybe even juxtapose what Hamer had to say about police violence and answers before to what Tamika Mallory had to say in 2020. That’s just, I think, a fascinating way to grapple with the topic and to get students to see the role of women leading in this. I’m giving national examples of the national context, but you could do the same thing transnationally. And my work may be useful.

Hagopian: I think that my next lesson is Fannie Lou Hamer and pulling quotes and articles from The Red Record, as well. That’s a brilliant idea. I haven’t checked that archive out yet, so thank you for that suggestion.

Well, I want to talk a little bit about the history of the police, as well. I think many people who are shocked by the behavior of police today — when they see these videos or they see Black people being brutalized — they’re only shocked because they’ve been mistaught about the police.

I had a very personal experience with that in the last few weeks, because my own son is in first grade and he got a worksheet home about three weeks ago from a company called Education to the Core. They sent home a worksheet called Police Protect Us and the passage there said,

Police work very hard to keep us safe. They drive in police cars and solve problems that they see while driving. The police cars ride on motorcycles, bicycles, and even horses. They solve crimes and help with emergencies. They make sure people are driving safely. They make sure people are following the law. Their jobs are very important. The next time you see a police officer, make sure you thank them for keeping us safe.

Then there were several questions on this worksheet. First, it says what kind of transportation, and my sons wrote “cars.” Then it said, “What are some of the things they do?” My son wrote, “They pepper spray people like my dad.” Because in 2015, I gave the final speech at a Seattle Martin Luther King Day Rally — it was on my son’s two year birthday — and they pepper sprayed me about a few minutes after I gave that speech, just straight in the face for no reason. That’s given him a very different idea of the police. He immediately saw this assignment for what it was, because when they said, “What do you think police officers do? Why do you think police officers’ jobs are important?” He wrote, “The people who protect us are nurses, doctors, and ambulances, but not police.” Then you see that the form even asked him, “What would be another good title for this story?” He just wrote, “Police don’t protect us,” which I think is A+ work if we have to reduce our kids to grades.

But, I think teachers in this session today are really committed to teaching outside of the textbook and this kind of racist worksheet. So I hope you can help us today with what they can be teaching about the origins of police. Because I think once you know about where they come from, it exposes so much of what we’re taught about it. Also, if you could tell us more about when and how police forces developed.

Blain: I think that assignment is probably reflective of the larger narratives that we tell, as you note in textbooks. But I would say just mainstream narratives that we like to tell. That is one particular perspective; it’s a perspective of a white person. So, the U.S. in that story isn’t reflective of everyone. It’s certainly not reflective of Black people. You certainly could not talk about Black people’s experiences in the U.S. or anywhere and suggest that police are protectors. I mean, this is definitely wishful thinking, and the kind of narrative that has ultimately made it possible for us to find ourselves here, where people are surprised, or at least some are surprised and somehow shocked that everything that’s been going on for the last few days finally came to the surface.

But, as we all know, this is new and what I think will be useful in this moment as you’re teaching about the 2020 uprisings, one of the things that you absolutely have to do is to go back to slavery. You have to talk about slavery, you have to talk about slave patrols, and you have to help students draw the connections to recognize that American policing comes out of this racist context, a context in which the focus or the purpose of the police, just in the very beginning, was meant to police and control Black people’s lives, to limit their movement, to make sure that they would be kept and oppressed. And that continues.

Even after slavery ended with the Civil War, what we saw then are the creation of these forces, initially informal groups of white men, but with time, by the period of Reconstruction, certainly, more uniformed and organized within cities. What they’re meant to do is function in the same way as slave catchers and function in the same way as slave patrols, which is to now uphold slavery. Now upholding Black codes, which ultimately function the same way. I mean, Black codes were meant to uphold white supremacy, as slavery was meant to uphold white supremacy. As you move throughout history, by the time you get to the 1960s, it’s not at all surprising that police officers are in full resistance to activists who are fighting for civil and human rights. Absolutely, I don’t think we should ever lose sight of that.

The other thing, too, is when we talk about lynching, which I just referenced earlier with Ida B. Wells, lynching was only able to really thrive across the United States because of the function of the police to support those who were doing the lynching, and sometimes to be the actual ones doing the lynching. You see that in Ida B. Wells’ writings. So, I think as we’re discussing this moment and teaching this moment, I do want to give a book recommendation, which I should have mentioned before. If you’re just not as familiar with the history, and you just want to figure out ways to teach it, this is a book called Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas. The author is Sally E. Hadden and this is published by Harvard University Press.

But that’s just one example. What you might do is maybe just take a close look at that book or other books and see if there are passages you can assign, or if there might be primary documents that you may be able to access. Certainly, there are countless databases where you can find ads, like an enslaved person ran away and the enslaver would post an ad in a local newspaper to try to find that person. There are databases that are just filled with hundreds of these kinds of ads. So you could pull those and help students, maybe break up into groups to talk about, to write about, and then draw the parallels to see what are the similar ways that white people were trying to control Black people’s lives and movements in the context of slavery, and then juxtapose that to the current moment with policing.

So, there are ways I think you can do that. And if you don’t want to go back to slavery, quite frankly, you could focus on the 20th century. You could focus on the 1960s, and still get to the heart of the point, which is that as much as we would like to believe that police officers are meant to protect, that’s simply not the case for Black and Brown people in this country.

Hagopian: Absolutely. And I should just tell you that that worksheet was in the midst of a whole bunch of other worksheets, and the teacher didn’t really see it. I’m proud of my son’s teacher, because she went and challenged the company when she found out about it, and as of right now, she’s trying to get them to change or remove it. So, that’s been a really important struggle.

I love your ideas for how to begin this conversation about the roots of policing and the function and role of police in our society. Because too often we get stuck in this bad apple narrative and we look at the particularly racist police and so the things they have done. And to me it, obviously it’s horrifying when there’s a particularly racist police officer, but it’s not so much about which ones are good and which ones are bad. But what’s the role of policing in society? Where did it come from? What are they designed to do? And I’m just so inspired by people who are really getting at the roots and talking about how we could defund police and use that wealth to provide social programs. We could fund our schools, we could provide trauma counselors, I mean, all the things we could do to support our youth rather than continue with this kind of school-to-prison pipeline. So, those are some great ideas.

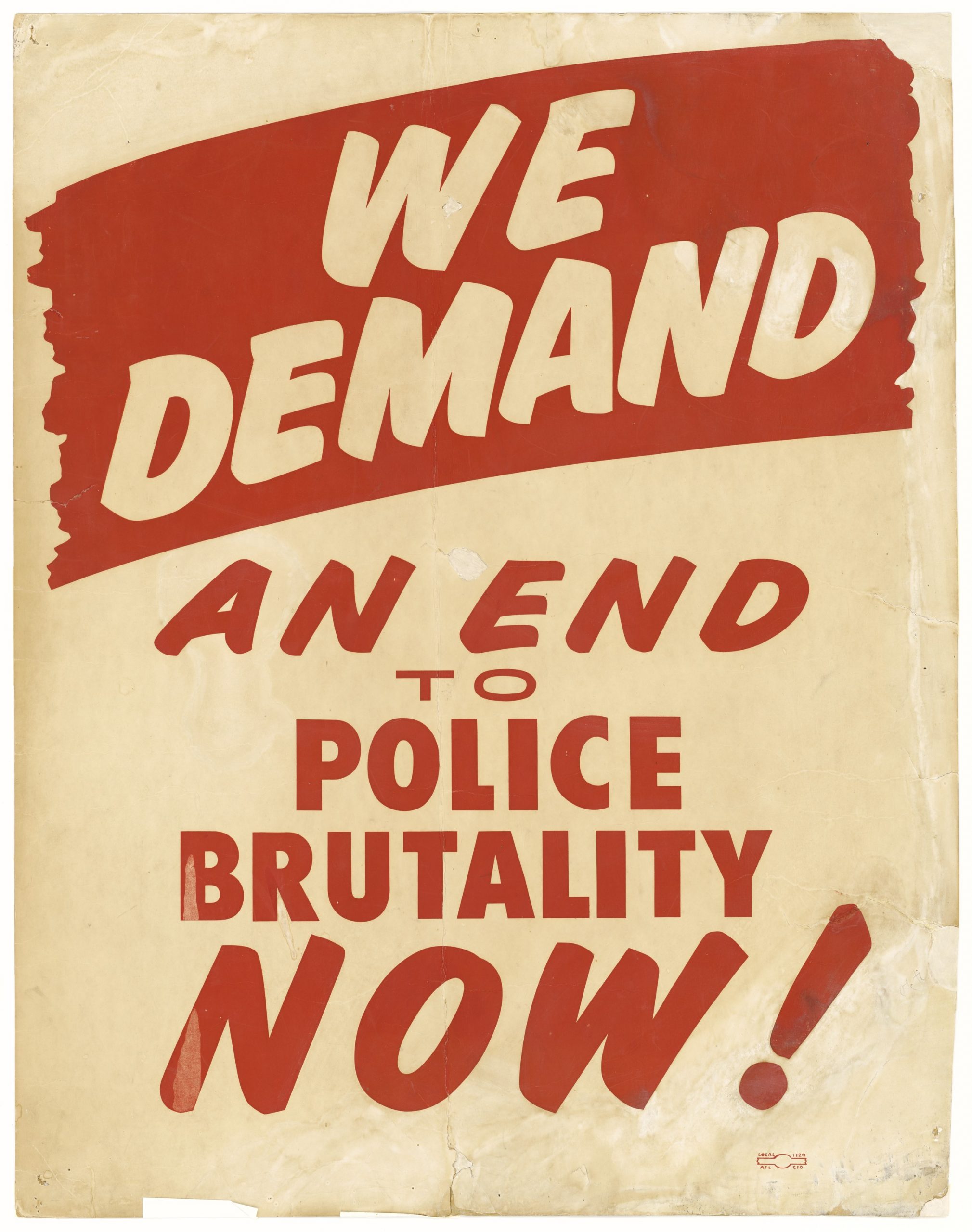

I think that we have to begin teaching this history, and I think this moment also demands that we teach about the history of rebellions to police violence, as well. So, I’m hoping you could talk more about some of the highlights in the struggles against police violence.

Blain: Yes. I believe everyone should have received a copy of just a short article that I wrote on Black women’s organizing against police violence and brutality in New York City in the 1980s. I wanted to circulate that because, as much as we do have to talk about the problem of police violence and police killings, I want to make sure that we’re also bringing into our teaching the narratives that help students understand the way Black people resisted and continue to resist, and the way thatBlack people stand up to the police. We certainly see that historically, much, much earlier than the 1980s example that I shared.

But I share that example because I thought it was useful within a contemporary moment where many of us are familiar with, but with the mothers of the movement. I’m speaking about a group of women, I think, off the top of my head about seven women, who were for the most part mothers. But I believe, also, one person’s a grandmother. I think there’s even a sister included in the group, but individuals whose lives have been touched devastated because they lost a loved one to police violence [or] to police killing. In 2016, in particular, the mothers of the movement were very, very popular in the national dialogues because they were often traveling at the time with Hilary Rodham Clinton, so we would have seen them in a context speaking out about police violence.

The example I shared for the 1980s, I think of that as a high moment, and I say that, obviously, all of this is within a context in which we see so many terrible cases. In New York City, the police killing of Michael Stewart in 1983, and the police killing of Edmund Perry, the police killing of Eleanor Bumpurs. All of these things are happening at this moment. But what is powerful, I think, in the narrative is that here you see two particular women, Veronica Perry, and Mary Bumpurs, who come together. And not just by themselves, I mean, other women join the movement too, who come together to try to organize around this issue, to resist, to try to come up with strategies for confronting it, to be very vocal.

And it was and what you can tell in their lives, I think for the two of them, they were certainly involved in political activism in different ways, leading up to the dreadful moment where they lost their loved one, but that particular moment becomes a turning point, and they sort of turn their grief into political action. We see that in the post 1980s. We see that certainly with Eric Garner’s daughter, but also Eric Garner’s mother, who I believe we just saw yesterday attending the memorial service of George Floyd. So I think as much as this is a very painful narrative, and we have to point out the problems, and we have to make sure that our students are cognizant of this, I think we can use these sorts of examples to help them see how Black people responded, how Black people came up with energies to challenge police violence. As much as we can talk about the fact that we have our victims within this narrative, we’re not just victims in this narrative that we are agents of change, and we are committed to coming up with strategies to confront these issues.

Hagopian: No, thank you. I really liked your response there. I’m just reflecting on it, because I realized that I haven’t really incorporated enough in my teaching about the families organizing for their lost loved ones. I work with families here in Seattle who have lost their loved ones. Charleena Lyles was a pregnant mother of three children when the police entered her apartment and killed her in her own apartment in front of her kids. We’ve worked with the family, and the strength of the family is what gives me inspiration to continue doing this work. So yes, let’s teach about the history of families, who are not just victims, as you say, but also turn that pain into power and organize and fight back. And thankfully they have.

So, I have one last question before we move to breakouts and we’re at time, so we’re going to have to be somewhat brief. But we can start the conversation about the overlapping crises that are occurring right now that have produced this rebellion. We have the COVID pandemic, we have an economic collapse, we have voter suppression, we have this authoritarian in the White House, we have violent policing and structural racism overlapped on top of all of these crises, so I hope you can just say a word about what caused this uprising and where you hope it goes.

Blain: I think, for many of us, certainly seeing the video of George Floyd just sparked outrage and frustration. I think I heard someone describe it just recently as the straw that broke the camel’s back. I think it’s very much a part of a larger issue that we’ve been dealing with. I mean, at the heart of the issue is white supremacy and structural racism. And, of course, here we are in 2020, where for the last three months we have been battling COVID-19. We’re also dealing with the reality, the data reveals to us clearly that Black people, in particular, are contracting the virus and dying from the virus at a significantly higher rate than other racial groups. Then we’re in an election year, and we are in a situation where we have someone in the White House who, as far as I’m concerned, people could care less about, certainly Black people and Brown people in this country. All of that plus just a range of problems, like the ones you mentioned, it just all bubbled to the surface and people had had enough.

Of course, mainstream media will focus on things like destruction of property, like looting, and oftentimes use those as distractions to somehow suggest that we can’t even talk about the larger issues here because look, someone burned something down, or someone broke something. But the reality is that even those kinds of expressions are reflective, I think, in a larger sense of the fight for economic justice; that there’s so much economic inequality, and educational inequality. And fine, I mean, I think most of us, probably all of us, will say that we’re not endorsing acts of violence, per se, but think about the kind of symbolism, so to speak, behind someone breaking some luxury store. I mean, I think we see the surface, but we have to go deeper in understanding what it means to be Black in this country, where you’re constantly at the bottom of the economic ladder, even educational inequality. It feels like everything’s coming together at once and coming together at this moment.

The last quick thing that I’ll mention is just thinking about the context of Trump. I was reflecting on earlier moments in our history where we’ve been at a similar place. I thought about 1957, with the Little Rock Nine. I thought about how, in Arkansas, you know, Governor Faubus, how he tried to bring in the Arkansas National Guard to block these students from integrating the local high school. And the response to that, at the national level, was having President Eisenhower send troops in to say, “Listen, we’re going to enforce the law. We’re going to make sure that we enforce the Brown decision of 1954.” But now we’re in a position where we can’t even imagine that kind of intervention, like we don’t even have someone in the White House who will take that step. To the contrary, he’d be the one sending in people. If you think about the similar scenario, he’d be the one sending people to stop the integration of the school. So, it’s just a very painful and frustrating moment to be in. And I think all of it just came to the surface, and people had just had enough. So they took to the streets. And some people burn some things down and some people did some other things, but in the end, I hope that, collectively, we stay focused on the fundamental problem here, which, as I said before, is white supremacy. Because we could talk about looting, talk about destruction of property, we could talk about a hundred different things, but if we don’t actually uproot the problem, then we’ll find ourselves back here, over and over again.

Hagopian: Thank you so much for focusing us on what’s important, like the great leader here in Seattle, Nikkita Oliver. She’s been in the streets protesting and organizing for years, and she gave a speech yesterday, or in the last couple of days, saying, “We can buy new cars and new windows, but we can’t buy a new George Floyd. We can’t buy a new Breonna Taylor.” So, we really need to focus on what the real struggle is about uprooting institutional racism and an economic system that profits off of it, as well. So, thank you for focusing all of us educators on how we can bring that into our classroom.

[breakout rooms]

I hope that we can end with some final insights from our incredible guest with us here today. I want to ask about the role of social media today in the rebellion. So much of our youth are on social media and are using it to help propel this movement. And I wanted to end with that. I’m going to turn it over to you, Keisha.

Blain: Sure. There are several things I would emphasize. I think the first is that, as we all know, social media has been such a powerful tool for organizing. Even now, we’re seeing that happening within the context of the 2020 Uprising, but I was even thinking about a project that I was involved in in 2015. As many of you know, I collaborated with Chad Williams and Kidada Williams on the Charleston Syllabus. It started off as a hashtag on social, on Twitter, and it provided a way for educators — surely the three of us but not just three of us — educators all over the country to come together to recommend resources, readings that we ultimately put together on a list.

We also put together a book, The Charleston Syllabus: Readings on Race, Racism, and Racial Violence, which by the way, it’s always a funny thing when you’re trying to personally promote. I prefer promoting other people’s work than my own, but if you’re looking for something else to add to the conversation, you may use the Charleston Syllabus in your teaching.

The only other thing I would emphasize is that, on the one hand, yes, social media is great for organizing. It has been, I think, an effective strategy, a tool, certainly, and a venue for people to come together, for activists coming together. We also have to be mindful that social media is also a potential way for movements to be squashed or movements to be infiltrated. As we’re now using a platform at this moment, thankfully, we haven’t had to deal with some of the things that people have experienced with Zoom bombing. But, the point is that you don’t quite always know who’s in the room, and you don’t know when people are present to be a part of a conversation or simply to surveal there for whatever purpose. That’s just something to keep in mind, just knowing that it’s useful.

But there are limitations, and sometimes I think social media becomes the first point of contact. But, I think, oftentimes it’s useful to start there and get people together, connected, and then get offline and actually have private conversations. As private as you can, given the circumstances today. That’s all I’ll say.

The only quick other thing, too, that came to mind for teaching, it depends on your style of teaching and on the grade, but you may decide to utilize something like Twitter as part of your teaching. One of the things that you could do is come up with a unique hashtag for your class. In the fall, you could ask students to go on Twitter at a particular time, you can have a Twitter chat that either happens, maybe it’s connected to the course or teaching. Or, at another time, if you’re allowing students to use laptops in the classroom, you could try a Twitter chat that involves other people. There are other creative ways that you can try to use social media to enhance your teaching, and students may find it to be a lot of fun, something that gets them out of the usual kind of ordinary process of being a classroom and going over texts and so on. I’m happy to talk to anyone about that more, if you would like to explore those kinds of possibilities.

Hagopian: Well, thank you so much, Dr. Blain, for your insights today. You have really inspired me to add to my curriculum the Charleston Syllabus, wish is so powerful. I think we drew on that for the Black Lives Matter at School curriculum, as well. So, laying that groundwork was so important, and all the insights you shared with us, I’m really thankful for what a rich conversation we’ve had today. I hope everyone here has gained a lot from this conversation and will recommit themselves to teaching for Black lives today in this moment, and supporting our youth in changing the world.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Resources

Here are many of the resources recommended by the presenters and also by participants in the chatbox. More resources from this session are posted at Teach the History of Policing.

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was learned

Responses to the question: What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today and what may you do with what you learned?

Recentering our history and education around resistance and creativity instead of just the oppression or violence forced on Black communities and individuals. The importance of the role of police throughout history and the importance of primary sources in creating context between events.

Resources and insight to be able to have a large group conversation with students and colleagues — particularly in response to/countering the ideology of those who have family members who are cops and might be really struggling to understand this fight/rebellion/movement for justice.

Keisha’s idea of using primary resources about the history and impact of lynching and juxtaposing those to contemporary articles and speeches on police violence/brutality.

Emphasis on the importance of teaching the history of resistance so our students can see the history of police, but have it combined with themes of resistance, empowerment, and hope so it can inspire their organizing.

Depicting agents of change, instead of purely victimization history that reinforces and furthers trauma and takes power from the students.

I have been looking for how to better understand the history of the police to deconstruct my understanding. I will be doing more work on how the police have impacted our kids of color and communities of color.

A reminder of the role of Black women (Wells and Hamer) in the early police abolitionist movement. I need to read and learn more.

I need to include the history of policing in my U.S. History course.

Dr. Blaine shared how to teach with the Red Report and current writings as paired texts!! Going to try that next week.

I loved hearing Dr. Blaine discuss Ida B. Wells and Fannie Lou Hamer and her ideas of having students go straight to the source and read/listen to their own words about their activism. Agency. Connecting not just the struggle over time, but lifting the examples of students/young people/ and organizers so that they have the power to make a change. I am refreshed and committed.

As a social studies teacher, learning about and getting resources on the history of policing and the slave patrols will be invaluable for my teaching.

Encouragement from peers to keep pushing forward in progressive curriculum and curriculum hacks.

Gaining students’ trust prior to these lessons.

The Charleston Curriculum. The community. The energy.

Incorporating the history of policing into my curriculum, making sure that students understand the connection between police violence and civil rights (now and then).

From the talk I learned to equate lynching with current police murders; use for discussion. During the breakout I learned ways I can participate in the protests when I can’t do so physically due to disability.

The committed devotion and critical consciousness of Jesse and Keisha and the evident work in self-actualization that they have done. Especially Jesse as a father and educator and activist.

The idea that police killings function as lynchings, with the same result, and with the public spectacle also there.

In our small group, a fellow teacher pondered about the role of the gap between life experiences of people of color and our curriculum in our classrooms . . . does the root of many of our problems lie in that gap? I will be thinking about this for a while and working through how to best address that gap.

I teach US and AP US History and the only narrative I’ve come across is the “bad apple” and especially the “bad Southern apple,” which makes systemic racism invisible.

I liked the idea to compare the work of Fannie Lou Hamer with Tamika Mallory, tying in history with the current day is always a great way to get students engaged.

Reframing the (damn looting) conversation with historical examples and stories of structural racism . . . . Ida B Wells, student-athletes, roots of police violence, so much more.

I am thinking about Dr. Blain’s discussion of bridging the early activism of women/mothers with that of modern activism.

To get out of the “it’s just one bad apple” story line and focus on structural racism. To learn more about the history of policing so I can teach more accurately.

The question that interested me the most was whether or not police killings are essentially lynchings.

Incorporating trauma-informed practices when we teach traumatizing history (still need help with HOW to do this, but reminded of the importance of paying attention to this).

Making explicit the connections between the racist and oppressive history and role of the police in the contemporary uprisings

The history and root of policing based on slave patrols designed to control Black lives.

The most important part of today’s session was the question: How does the history of policing show up in your curriculum? That history is absent from my curriculum and my teaching. I know that I have to provide this important historical context for my students so that they can understand the movement today for Black lives.

It is the teachers who are uncomfortable with complicated/difficult topics, not the students.

I learned that I need to examine all books about police that I use with my students, as well as how it is considered as a career option to youngsters. I also need to educate myself on the history of policing.

There are so many valuable resources out there to teach history, to teach life, and they do not make it into school mandated curricula. We need to bring it ourselves until publishers are demanded to include them.

Educators have a critical role to ensure students understand the roots and historical evolution of policing in order to place it as a structural/systemic problem rather than the propensity to see lynchings as isolated events or as the “bad apples” rhetoric.

Dr. Blain’s ideas about understanding the role of spectacle in police brutality — drawing connections between state-sanctioned violence in the form of lynchings and police killings. As a teacher of media studies, I want to challenge my students to deconstruct the messages embedded in all media in order to understand themselves and the world around them better. As a high school teacher at an international school in Tokyo, I encourage my students to make connections between the ongoing fight for civil rights in the United States and their own lives in Japan.

The importance of teaching historical foundations of police — the origins of policing, its functions, and its role in society.

I appreciated the explanation of the origins of policing in the U.S. and its link to the atrocities as well as the general misconduct of modern-day police. I also appreciated the raising of Ida B. Wells and others that fought against lynching and its support by law enforcement.

I learned how troubling the origins of police in U.S. are. Somehow I thought the establishment of police had more to do with protecting private property (which unfortunately enslaved people were considered to be).

That “lynching” is used to apply to “state-sanctioned violence.”

I learned about the Red Record and ad databases (patrol) to share primary sources.

The suggestion to compare and contrast the writings of Black women freedom fighters like Ida B. Wells and Fannie Lou Hamer against current op-eds and speeches from freedom fighters like Tamika Mallory or Bree Newsome was such a great idea! I definitely want to use those framing structures to get students to think more critically about their role in the current state of affairs.

I need to immediately start referring to this as a Rebellion in my discussions with my students. I need to read more for my own background knowledge so I can present it in-depth and expertly to my students, I need to incorporate police brutality and resistance in all of my history units.

Teaching the current movement in the context of other historical movements (slave patrols, Black codes, 1935 women protesting in England).

The direct connection between slave catchers and today’s policing, the transnational nature of Black organizing and movements (historically and today), reminders about the importance and significance of naming (civil rights, human rights).

The reminder again that it is critical when teaching about oppression to also teach about rebellion and JOY. It is a good thing to hear over and over again and to keep working to teach that way.

The format.

I appreciated the practicality of the session and the breakout rooms.

The really liked the breakout rooms. I wish we had a few more minutes, which is a good sign that it was probably close to the right amount of time.

The breakout room, with teachers outside of my context, was critical. I knew to step outside my school community and hear from more voices and perspectives.

I loved the breakout groups after listening to their discussion. Having the chat was very helpful too.

This is the second session I’ve attended (Black Panther women was the first). The breakout groups are a valuable tool to allow participants to share ideas and meet others.

The format is consistently amazing. I love how you explained the pedagogical reason behind the breakout groups. Would love to have more time with them, since we only go through the first question this time, but don’t want to lose any of the main conversation time!

I thought it went well this time, everything went smoothly for me.

All was good. still noticing not all yt participants know to step back. in particular lessons/zooms where we center Black scholars, Black hxstory, etc. it is necessary to communicate that yt participants must be the last to speak, if at all, and listen instead.

The format was awesome! Would love more time in breakout rooms but wouldn’t want less time with the presenters either 🙂

Great conversation! I loved that the topic adapted to reflect the current events.

It worked well. My first time with a Zoom breakout room.

The breakout groups and chatbox were an awesome way to connect with fellow educators and share resources.

The format was great. I was skeptical of the breakout group, but ended up learning a lot from educators across the country and the world, and gained some great resources.

As always, everything was really informative and inspiring.

Although the size of the forum was incredibly large (300!), it didn’t feel crowded. I like the back and forth between the presenters, and of course, the breakout room allowed us to share and process this information.

This time we DID have enough time in breakouts! I had to step up and facilitate a bit because I have seen it for several weeks. BUT the best thing was that our high school student participant led us off with his voice!!!! I want to be in the classroom of every one of those teachers!

It was my first experience in breakout rooms and it went well. I was impressed with the amount of sharing that went on . . . while not particularly relevant to me as I am not a teacher but I do have teachers in the family and as a parent and grandparent, now have the information I can share.

I think the facilitated discussion in the whole group and breakout rooms was great. It would be great to have a few small breakout rooms to allow a conversation to process the amazing things we heard, but this worked for the time constraints.

I thought the breakout session was perfectly placed midway through the discussion. I appreciated that Jesse and Dr. Blain were in conversation — Jesse was a great facilitator and asked important questions, while also offering his own experiences and insights. The size of the full group was awesome!

Great format. ALWAYS LOVE the breakout rooms and meeting and talking with people from all over the country.

Keisha N. Blain and Jesse Hagopian’s presentations and conversation were wonderful. I particularly enjoy breakout rooms and ours was very well facilitated and rich.

Breakout room was great, I really liked that it was so small. I was intimidated to speak, but the facilitator was wonderful.

I almost left before the breakout groups, and while my breakout group was only two people, it surpassed my expectations — we had a good conversation (though it was initially a little confusing since I was expecting a larger group) and I appreciated the accountability to engage with the material and one another.

Additional Comments

Dr. Blain and Jesse Hagopian are AMAZING. I learned so much! This was INCREDIBLE professional learning and I am grateful that you’ve created this space and opportunity.

I love seeing folks from so many regions/contexts and so on. Thank you very much!

Continue to expose truths to our youth and educators. So very important.

Thank you all so much! I read A People’s History of the United States by the great Howard Zinn in high school. Now as an elementary educator (who is also a white, straight male) this work is critical to integrate into my classroom.

These sessions are the highlight of my week.

I have so much more hope today than yesterday. Thank you!! Jesse’s smile at the end was priceless!

Thank you so much! Totally worth getting up at 3:00 am. I hope to join more sessions in the future.

Thank you for the session today. This helped me to process what is happening right now and to think forward about how I want to show up for my students.

I am grateful to you for your leadership. It is a bright spot each week. Also, Mr. Hagopian’s story about his son was instructive for me.

Keep doing what you’re doing! I appreciate that you all are amplifying the voices of Black female/women historians.

As always — and especially this week — I so appreciate what I learn here and how it inspires me to think in new and important ways to do my little piece in helping to educate my students to build a better future. Today was wonderful — as always — but today was especially nourishing for our souls, as well as our minds.

Presenters

Keisha N. Blain is an award-winning historian of the 20th century United States with broad interdisciplinary interests and specializations in African American History, the modern African Diaspora, and Women’s and Gender Studies. Her research interests include Black internationalism, radical politics, and global feminism. She is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Pittsburgh, President of the African American Intellectual History Society (AAIHS), and a 2019-2020 W. E. B. Du Bois Fellow at Harvard University. Blain is the author of Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom, which won the 2018 Berkshire Conference of Women Historians Book Prize and the 2019 Darlene Clark Hine Award from the Organization of American Historians. The book was also a finalist for the 2018 Hooks National Book Award; and selected as one of the best history books of 2018 by Smithsonian Magazine. Blain is also the co-editor of three books: Charleston Syllabus: Readings on Race, Racism, and Racial Violence; New Perspectives on the Black Intellectual Tradition; and To Turn the Whole World Over: Black Women and Internationalism. Follow her on Twitter @KeishaBlain.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, and editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn