“One cannot study Reconstruction without first frankly facing the facts of universal lying,” explained scholar W. E. B. Du Bois in 1935. Spurred by that directive, we have just posted Five Ways Textbooks Lie About Reconstruction by Mimi Eisen as an addition to our national report, Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle.

Eisen and Zinn Education Project intern Hannah Grace Howell examined some of the most commonly used U.S. history textbooks and identified five themes. Listed below, Eisen describes these in more detail with textbook examples in the article.

- Textbooks center Confederate states and ex-Confederates.

- Textbooks treat white people as subjects and Black people as objects.

- Textbooks marginalize Black experiences and achievements rather than centering them as the main narrative.

- Textbooks downplay the pervasiveness of white terror and fraud, distorting the role of the Ku Klux Klan in a much larger network of racial violence.

- Textbooks ask if Reconstruction was a success or failure, obscuring the white supremacist counterrevolution that cut short its historic gains.

We offer you this description of the first point and invite you to read and share the full critique.

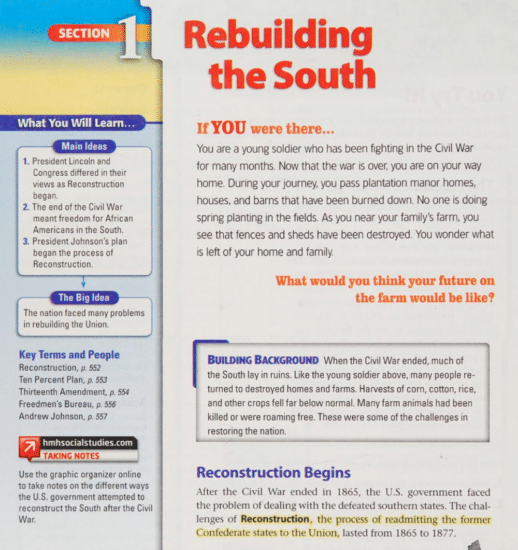

The Reconstruction section of Holt McDougal’s United States History: Beginnings to 1877 opens with a prompt: “If YOU were there. . .” The text urges students to imagine themselves as former Confederate soldiers traveling the South and witnessing, with dismay, the destruction of “plantation manor homes.” This narrative encourages students to view Reconstruction from the perspectives of those who fought to preserve enslavement.

The main narrative begins below, introducing Reconstruction as the federal government’s “problem of dealing with the defeated southern states.”

This page alone is a stark example of what most textbooks do, but shouldn’t: amplify discrete perspectives of white political figures and former soldiers in the aftermath of the Civil War. They narrow its focus, often establishing Reconstruction as a series of clashes between President Andrew Johnson and Congress to readmit the rebel states — or as the daunting task ahead of ex-Confederates to rebuild the war-torn South without slavery.

Meanwhile, as Lerone Bennett Jr. chronicled in Black Power USA,

Black people were busy building institutions that were dangerous to the peace of biased white men.

They were ignoring orders from ex-Confederates; meeting in courthouses and fields to plan election strategies; gathering for picnics and parades; observing trials and debating legal issues; determining school subjects and teachers; establishing newspapers that brimmed with short stories, poetry, and advertisements for community events; and shaping the meaning of freedom in myriad other ways.

But textbooks rarely characterize the 1860s by this rebuilding. They do not tell students that Reconstruction was a revolution to create a more just society from the ground up, or how many issues and movements today have roots in that struggle.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn