By Nancy Raquel Mirabal

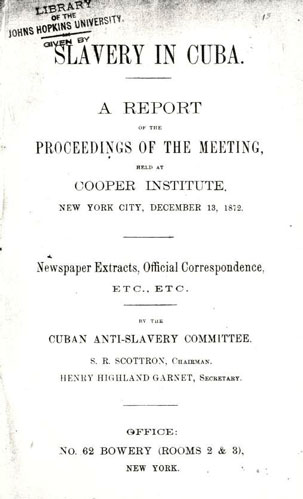

Slavery in Cuba. A report of the proceedings of the meeting, held at Cooper Institute, New York City, December 13, 1872. Click to read in full at the Colored Conventions Project Digital Records.

On a cold December evening in 1872, hundreds of African Americans and “a few foreign negroes” attended a meeting organized by the newly formed Cuban Anti-Slavery Society. There, inside the Great Hall of the Cooper Institute, also known as the Cooper Union, Samuel Raymond Scottron called the meeting to order and welcomed the audience who had gathered that evening to hear Reverend Henry Highland Garnet speak on slavery and insurgency in Cuba.

The organizers, who were all men, were impressed by the large turnout and especially with the number of reporters from major New York newspapers who attended the event, including correspondents from the Evening Mail, the New York Sun, and the New York Herald.

The reporter for the New York Times, however, was not as impressed; in a brief column entitled “The Cuban Negroes — An Enthusiastic Meeting for the Cubans Last Night,” he observed that the meeting “was not largely attended, with less than 300 persons being present.” For Samuel Scottron, however, the fact that close to three hundred “colored citizens” braved the cold night to protest slavery in Cuba was extraordinary.

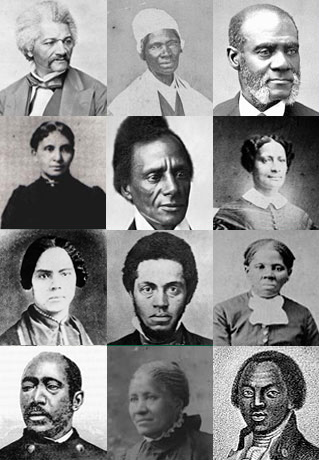

The meeting took weeks to plan. Concerned that Cuba was one of the last countries to abolish slavery and determined to rally support for the Ten Years’ War, the founding members Samuel Scottron, Peter W. Downing, J. C. Morel, John Peterson, Philip A. White, John Zuille, David Rosell, and T. S. W. Titus circulated a call in early December inviting “the Colored Citizens of the United States” to attend a meeting protesting slavery and supporting the Cuban Patriots who “have already decreed and put in practice the doctrine of the equality and freedom of all men.”

The call authored by some of New York’s most respected African American abolitionists, newspaper reporters, inventors, and business owners implored their fellow “colored citizens” to view “with abhorrence the policy of the Spanish Government during the past four years in the island, both, [sic] for its unnecessary and inhuman butcheries that have taken place under its rule, and for the tenacity with which they cling to the barbarous and inhuman institution of Slavery.” . . .

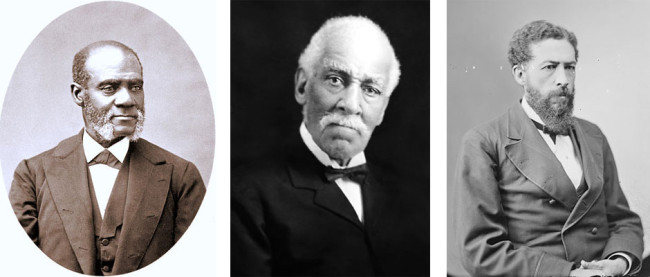

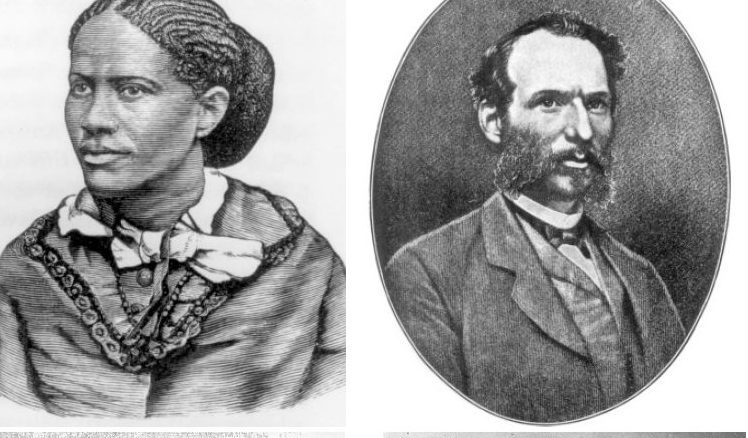

Rev. Henry Highland Garnet, George T. Downing, and J. M. Langston.

The resolutions that Scottron read that evening were remarkable in how they directly connected the plight of free African Americans with enslaved Cubans. Well aware of their status as “colored citizens of the United States,” the members used their “rights of freemen” to advocate for Cubans who are “now in a state of slavery, undergoing the same sad experiences of ourselves in the past.”

Based on an extracted memory of hemispheric slavery, one that recalled “full well the cruelties of family separation, of the lash, constant toil and pain, of inequality before the law,” the resolutions echoed the stirrings of an Afro-diasporic imaginary rooted in notions of a shared experience of slavery, violence, injustice, and belonging. They also signaled, albeit not in text or procedure, a larger and difficult dialogue on the meanings of freedom, revolution, and civil rights during a period defined by post-Civil War policies, Reconstruction Amendments, and the Ten Years’ War in Cuba.

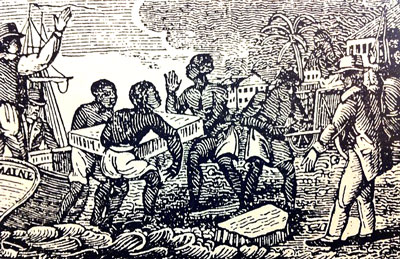

Enslaved people unloading ice in Cuba, 1832. Source: Public domain

Why would African America men, “so lately possessed of their liberty,” organize around slavery and insurgency in Cuba? To what extent did their reading of freedom reveal masculinist desires and longings to destabilize and reimagine the self, while attempting to define the other?

In a speech the New York Times deemed “of considerable length,” Scottron spoke to the evolving discourse on civil rights, hemispheric freedoms, and nineteenth-century diasporic politics. Departing from past abolitionist rhetoric, which cautioned against supporting slave revolts and anti-colonial revolutions, he reminded the audience that there “may be those perhaps, [sic] who are opposed to introducing anything of a political nature in connection with that of emancipation,” hinting at both the legacy of African American involvement in anti-slavery societies and the recent passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. Aware of how the newly passed Reconstruction Amendments influenced the way African Americans viewed their place in the United States during the post-Civil War period, Scottron argued that since “our race enjoy all the rights of freemen in our Republic and, as a consequence, are respected as men everywhere . . . we should use all our efforts to ameliorate the condition of our brethren in other lands and endeavor to destroy slavery wherever it exists.”

Conscious that the task before them was “weighted with difficulties,” especially since those “whom we propose to free are not within our grasp” Scottron nonetheless affirms that such difficulties can be successfully surmounted. While directing the their gaze toward Cuba as a symbol and narrative was not new, this time around African Americans were constitutionally free, and for men like Scottron this meant putting those freedoms into practice. Grounded in a long history of African American leadership and participation in trans-American anti-slavery societies, the Cuban Anti-Slavery Society was the first organization founded by African American men in New York to focus primarily on supporting insurgency and ending slavery in Cuba.

This essay is excerpted, with permission of the author, from “‘With Painful Interest’: The Ten Years’ War, Masculinity, and the Politics of Revolutionary Blackness, 1865-1898” in Suspect Freedoms: The Racial and Sexual Politics of Cubanidad in New York, 1823-1957. Read the book to learn more about this Reconstruction era international solidarity.

Nancy Raquel Mirabal is an associate professor of American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park, author of Suspect Freedoms, a board member of Teaching for Change, and project director of Out My Window. Mirabal is a historian who has published widely in the fields of Afro-diasporic, Latinx, gentrification, and spatial studies.

Learn more in the Zinn Education Project national report, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction,” and find teaching resources on Reconstruction below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn