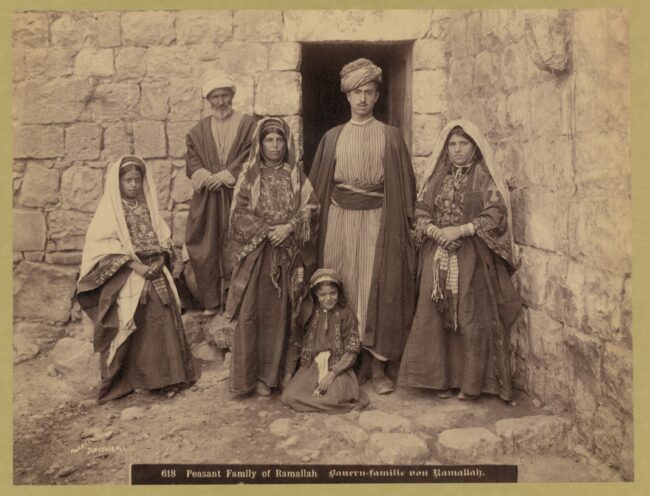

Palestinian family of Ramallah, circa 1900-1910. Source: Library of Congress Matson Collection

By Bill Bigelow

The historian-activist Howard Zinn was fond of saying, “If you don’t know history it is as if you were born yesterday. And if you were born yesterday, anybody up there in a position of power can tell you anything, and you have no way of checking up on it.”

There is nothing in the world today more in need of an accurate historical account than the violence in Palestine-Israel — or more infected with obfuscation. Many people’s historical reckoning seems to go back no further than October 7, 2023. Even those more committed to understanding the present in terms of the past often reach back only to the Six Day War and occupation in 1967 or the UN partition of Palestine in 1947 and the 1948 War for Independence — for Israelis — or the Nakba, the Catastrophe — for Palestinians. Or they may simply say: It began with the Holocaust.

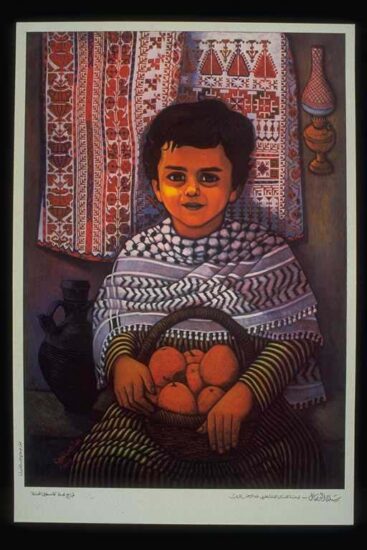

“A Basket of Oranges.” Source: Palestine Poster Project Archive

But as this activity demonstrates, the roots of today’s violence can be seen much earlier — from the first years of Zionist immigration and land purchases in Palestine in the late 19th and early 20th century, the expulsion of Palestinian peasants, the Zionists’ partnership with the British Empire to effect its goal of “a national home for the Jewish people,” and Palestinians’ gradual recognition of the sweeping nature of the Zionists’ ambitions. As Rashid Khalidi summarizes in his essential book, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, “the modern history of Palestine can best be understood in these terms: as a colonial war waged against the indigenous population, by a variety of parties, to force them to relinquish their homeland to another people against their will.” Seemingly to frighten teachers and students from grappling with the origins of today’s crisis, politicians, as well as corporate media and textbooks, have a thousand ways to warn us how “complex” the Israeli-Palestinian struggle is. And it is. But Khalidi distills this complexity in the simplicity of that single sentence. In a participatory way, the “Seeds of Violence” mixer/mystery seeks to do the same thing for students — applying that framework to the conflict’s earliest days.

And I want to underscore the “earliest days.” It may be an obvious point, but this activity does not deal with a huge amount of essential history: the almost-30 years of British rule in Palestine; British Mandate conflicts between Palestinians and Zionist settlers, between Zionists and British, between Palestinians and British, especially the Great Palestinian Revolt of 1936–1939; the rise of Nazism and the Holocaust; World War II; as mentioned above, the UN partition of Palestine and the violence of the Palestinian Nakba/the Israeli War of Independence and the creation of more than 700,000 refugees. The “Seeds of Violence” depicted in this activity happened before all these life-shattering events. The more I read about this early period, up to the beginning of the British Mandate in 1922, the more I realized how much of this history foreshadowed the conflicts to come.

The activity begins with the acknowledgement that there is tremendous violence today, but that the violence did not begin with the Hamas attacks on October 7 — it began long before. And that is the mystery students address in this activity: What is the source of this violence?

With this “mystery” as the lesson’s central problematic, students get a crash course in some of the foundational knowledge they will need to understand the real-world individuals they meet in the mixer — for example, that for centuries Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire; that Jews were victimized by pogroms and other forms of horrific violence in eastern Europe, and as a result, some Jews embraced Zionism, seeking a Jewish homeland of safety and community; Palestine was drawn into the Great War (World War I), with the Ottoman Empire joining the Central Powers and ultimately losing to the Allies; Palestine was invaded and occupied by the British, who came to control Palestine as a League of Nations’ “Mandate.”

Yeah, I know: It’s a lot. But students work with this information to create maps that help them visualize some of the geography of these events. And a bunch of this information is fleshed out in the stories of people students meet, so the aim of this first segment of the lesson is familiarity, not mastery.

In the mixer, students “become” individuals to bring this history, and more, to life. Note that they do not act anything out. They try to internalize their roles to represent to one another their characters’ experiences, opinions, and aspirations. There are 17 of them. Here is a summary. The Zionists and pro-Zionists include: Theodor Herzl, Viennese “founding father” and theoretician of Zionism; Arthur Ruppin, director of the Palestine office of the Zionist Organization, and a purchaser of land for Zionist settlement in Palestine; Joseph Baratz, Zionist settler, who fled pogroms in Russia as a teenager as part of the Second Aliyah (migration) of Jews to Palestine, and worked there in one of the first kibbutzim; Lord Arthur Balfour, the British foreign secretary, who issued the fateful Balfour Declaration, announcing British Empire support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine; President Woodrow Wilson, supporter of the Balfour Declaration and the Zionist movement; and Herbert Louis Samuel, British High Commissioner for Palestine during the early years of the British Mandate period. Two Jews in the mixer are anti-Zionists: the Sephardic Jew, Yosef Castel, whose family had lived in harmony with Arab Christians and Muslims in Palestine since Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492; and Pati Kremer, a member of the socialist Jewish Bund, which sought to transform rather than flee eastern Europe, and saw Zionism as divisive and numb to the exploitation of working-class Jews by capitalist Jews.

Three roles are Palestinian peasants: Ahmed Sharabi, evicted from his land by Zionists of the First Aliyah (migration from Europe), who bought Sharabi’s land from an absentee landlord; Mahmoud Khatib resisted his land being taken over by Zionists of the Second Aliyah, who also had bought it from a wealthy landlord in Beirut; and Razan al-Barawi who lived in Gaza and was caught between warring empires, the Ottoman and British, made a refugee and reduced to dire poverty. Shukri al-‘Asali, the Ottoman (and Palestinian) district governor of Nazareth, refused to approve the Zionist purchase of land from absentee landlords that would result in peasant evictions.

Scholars and journalists wrote defiantly about the waves of Zionist migration and the Zionists’ separatist vision for Palestine, which would turn Palestinians into “strangers in their own land”: Palestinian scholar Yusuf Diya al-Din Pasha al-Khalidi knew Theodor Herzl from his time in Vienna and wrote to him: “In the name of God, let Palestine be left alone”; Najib Nassar, the Christian publisher of the newspaper al-Karmil, wrote about Zionist land purchases and Palestinian expulsions; ‘Isa-al-‘Isa, editor of Filastin, wrote critically about the Balfour Declaration and the British-Zionist partnership during the early years of the British Mandate; and Musa Kazim al-Husayni, a leader with the Palestine Arab Congress organized against the discriminatory nature of the British Mandate in the years after the Great War. And finally, there is Elias Sursuq, one of a number of absentee landlords who took advantage of an 1858 Ottoman law to claim ownership of huge tracts of land in Palestine and later sold that land to Zionists, who were committed to empty the land of Palestinians.

In the mixer activity, students encounter different individuals’ perspectives as they circulate throughout the class, soliciting answers to eight questions — e.g., “Find someone who supports Zionism. … Why do they support Zionism?” And: “Find someone who opposes or is critical of Zionism. … Why are they critical of Zionism or oppose it?” One question encourages students to: “Find someone you have something in common with. Perhaps it is something important that you agree on. It could be that you have similar concerns, or similar hopes. … What is it that you have in common?”

Following the mixer activity, students write about people they met who made an impression on them — people who angered or puzzled them; people who they admired, people they want to know more about. They surface key themes in the early “seeds of violence” planted in Palestine. In post-mixer discussion and writing they begin to explore choices made in the late 19th century and early 20th century that created the conditions that would ultimately lead to the violent collisions that Palestinians and Israelis have experienced for the past 100 years. And, finally, in small groups, students assess: “Who or what in Palestine’s early history was ‘guilty’ of laying the groundwork, or somehow contributing to today’s violence?”

The fine print: Inevitably, an activity like this tells some people’s stories and leaves others’ out. I sought to give voice to Zionists confronting antisemitism who saw Palestine as a future national home, but also to Jewish opponents of Zionism, as too often Zionism and Judaism are conflated. I included Palestinian peasants because they were losing their land to Zionist settlement — and resisting — as well as Palestinian newspaper editors and activists, who came to awareness, thanks to this peasant resistance, about the Zionist movement’s ultimate aims for a Jewish-only state. From the beginning, the Zionists understood that they needed an imperial sponsor, and so I wrote key British roles, as well as one for President Wilson, a Christian Zionist whose side-taking foreshadows later U.S. sponsorship of the Zionist project in Palestine. And I included a representative of the wealthy absentee landlords, who in many cases were not themselves Palestinian, yet made immense profits off Palestinian land sales to the new arrivals from eastern Europe. Estimates vary, but at the end of World War I (referred to as The Great War in the mixer), Jews constituted a scant 6 percent of the population in Palestine; and not all of those were Zionists. The mixer’s “math” was not to have the ethnic representation in the role play match the ethnic percentage in the population — that would have led to almost every role being a Palestinian. What I aimed for was a collection of roles that could tell students a complex but coherent story about the unfolding tensions in historic Palestine — a story that would help them identify the “seeds of violence” that have grown so horribly today.

The individuals in the mixer are actual people. Although each role is written in first person, unless language is in quotation marks, the role’s narrative is my attempt to make the individual’s story more easily accessible for students. The literature that I drew on did not name any Palestinian peasants, so Ahmed Sharabi, Mahmoud Khatib, and Razan al-Barawi are not the exact names of peasants. I took a bit more liberty in the case of al-Barawi as I could not find the story of a particular individual who fled Ottoman-British fighting in Gaza, as she did, but all the information in the role is accurate. A caution with the stories of peasants: As Rashid Khalidi pointed out in a 1988 article, “Palestinian Peasant Resistance to Zionism Before World War I”: “Because those we have focused on could not speak for themselves in the sources which are left to us after seven or eight decades, we have seen their actions through a glass darkly, largely via records left by foreigners, who did not speak their language or understand their culture, who had little sympathy for them, and often were their enemies.” This is a necessary caveat. But to omit Palestinian peasants from this activity because we don’t know their precise names or have their exact words recorded would be to ratify the conditions that silenced them in the first place.

And another caveat: The people included in the mixer are mostly men. I wanted the roles in this activity to represent specific individuals, to the greatest extent possible; and not surprisingly, the people in history who left written records — the newspaper editors, scholars, politicians, diplomats, et al. — were overwhelmingly male. I did not want to imagine people into the role play who were not part of the historical record. Can students accurately inhabit the lives of the individuals they represent in the mixer activity? Of course not. Every activity that seeks empathy, that asks students to assume the personas of distant others — historically, culturally, geographically — is imperfect. This reaching for empathy — which strives for understanding, not necessarily agreement or approval — is the heart of social studies. Yet as teachers know, role plays can be tricky, sometimes risky. Before teaching any role play, I recommend reading the Zinn Education Project statement, “How to — and How Not to — Teach Role Plays.”

One more thing. In the mixer, I try to be as precise as possible with place names. Although there was no independent state of Palestine under the Ottoman or British Empires, Palestine was recognized as a definite place, and as abundant scholarship demonstrates, Palestinian national aspirations grew from the late 19th century onward. So when describing this region in the late 19th century through the 1947 UN partition, I refer to Palestine. When describing this area today, I use the term Palestine-Israel, to acknowledge this as a contested site, that Israel exists as a nation, that Palestine preceded Israel and also exists, albeit not as a nation state with defined borders.

Finally, the land tenure system in Palestine during the Ottoman Empire was complicated. I want to acknowledge Dr. Kristen Alff of North Carolina State University, who read these roles and tried to help me grasp the complexity of what was happening on the ground as the “legal” occupants of the land began to change. Thanks, too, to Dr. Stephen R. Shalom, emeritus professor of political science at William Paterson University, who read the entire activity and made valuable comments. Needless to say, any errors are mine.

Classroom Stories

I had been grappling for several weeks with putting together an engaging, challenging lesson on the Israel-Palestine conflict. I teach at a Title I school whose student body is incredibly diverse, and has begun slinging some fairly hateful language regarding this topic.

With the support of my admin, I moved forward with the idea of creating a mini unit. I teach Pacific Northwest History and their support of our scholars and their needs despite it not being what I “teach” makes me proud to work in the Renton School District.

The Seeds of Violence lesson was perfect. I adapted it slightly for my scholars, and added on a Question Formulation Technique and gallery walk as a hook. We have kept their questions hanging around the room to track which ones we answered.

Their questions and authentic engagement has blown me away. They WANTED to be challenged and this lesson has helped me to do that for them. It was laid out so beautifully and clearly. The roles themselves are so well written. To be able to support their exploration of this topic and see them focus on the genesis of the conflict instead of who is right and wrong has been very rewarding. We were also able to connect this topic to previous learning around Indigenous peoples in our state.

I used the Teaching the Seeds of Violence in Palestine-Israel lesson in my sophomore world history classes as we worked on a unit on the Middle East, and specifically current events in Palestine. Initially my students struggled to make a connection between the events of the late 19th century and early 20th century and the current apartheid state of Israel. Going through the Context handout was very helpful in showing students the connections between recent events and events from a hundred years ago when Zionist organizations really began to push for a homeland for the Jewish community.

That connection began to take shape in such an awesome way when we did the mixer the next day. It was amazing to see students begin to connect the current state of Israel and its policies towards Palestinians with the ideology and policies of Zionists and the British policies that allowed and encouraged those policies.

After we did small group discussions there were a number of groups who were able to connect this history of Palestine and the Zionist movement. Many students asked very pointed questions about why Britain would or could allow this, and we connected all of this to the theme of this semester which deals with the consequences of colonialism and how they inevitably exploit and destroy Indigenous populations.

The most amazing aspect of this lesson was my students’ ability to recognize the common themes presented in the story of Palestine with stories of other colonial projects we had studied including in India, the United States, Sudan, and the Congo.

Overall, this lesson was an amazing way to help my students understand the roots of the political issue that is Palestine and helped them evaluate many of the common misconceptions of where the conflict comes from.

I used the Seeds of Violence lesson in my sophomore World History class to give students a stronger understanding of the history in this area and how it has built up to the conflict today.

I first had students use the context sheet to familiarize themselves with important vocabulary and terms they would need to understand the different perspectives.

I then used the mingle activity as a hallway gallery walk and it was really helpful for students to understand different perspectives on both sides. The way they were phrased was on my students level and helped them get a deeper understanding about how different groups felt about the Zionist movement.

I had them use the essay prompt to reflect on the different sides and how both could be responsible for potentially planning seeds of violence. This prompted students to think critically and use the knowledge they had gathered from all of the activities to understand the complex tensions happening in this area and how it still such a major area of tension and violence today.

At our school, our 9th-grade global history team decided to do a version of Teaching the Seeds of Violence: Palestine-Israel because we loved how it prioritized personal narratives and met the department’s goals in our unit on World War I. I found that so many of our students, especially the Jewish and Muslim students, at 14 years old, considered themselves experts on the topic and were constantly on the lookout for teacher and peer mistakes. The reality was that many students relied on large monoliths of group identities, and the narratives in the activity were relatively successful in getting students to interrogate non-dominant perspectives in their lives. At the very least, it helped to highlight the human voices on this topic rather than relying on any one textbook to teach multiple perspectives.

We added three voices to the activity. A colleague found an additional source from the wife of a Jewish engineer who was a member of the first aliyah in 1890. She also found two more sources, one from William Ormsby Gore and Shmuel Yavnieli, that emphasized some of the differing perspectives within early Zionist movements. We wanted the students to have access to as many voices as possible. These sources came from The Origins of Israel, 1882-1948: A Documentary History by Eran Kaplan and Derek J. Penslar (University of Wisconsin Press, 2011).

Despite norm-setting and intentional work around the purpose of this activity and its connection to our World War I unit, we found that students were policing each others’ language, both in and outside the classroom. As a result, we did not feel comfortable using the idea of “guilt,” “innocence,” or “mystery.” We decided to require the students to read at least two perspectives and then answer a set of questions to prepare for a fishbowl conversation in class. In class the next day, we had students create a list of all the possible motives, goals, perspectives, and worries in a chart and then compare their lists with their peers. Finally, students engaged in a fishbowl conversation based on the essential questions from homework. The best part was that most of our students ended up reading more than 2 perspectives out of curiosity and because the narratives were easily digestible.

Overall, I think the activity was successful because it forced the students to slow down. They were so ready to jump to conclusions about how school, their peers, and their teachers would fail them. Parents reached out to us as well to interrogate the sources we used and ask about our thinking in planning this unit. I so appreciated this activity because even in those parent meetings, we could show them how we prioritize our goals in all our curricular designs, not just this unit. We got to reaffirm our shared values of multiple perspectives, with our broader goal being to interrogate the impact of human choices in order to imagine a more just world. I think that this opportunity to reiterate our mission as a history department helped to build broader trust between our department, our students, and their parents.

It feels like we all, especially young people, have been bombarded with images and videos of the violence happening in Gaza on their social media feeds. Students asked me during class one day about why these atrocities were happening and its causes, leading to a conversation about their desire to learn more.

What I and my students appreciated about the Teaching the Seeds of Violence in Palestine-Israel lesson was the wide breadth it provided for them to see for themselves the complex history leading to the injustices happening today. The mapping exercise allowed for students to critically analyze together about the global connections to Palestine and the forces at play. Together, they built a case for the top three “seeds” to present to our judge during a tribunal who weighed the argument.

During our contemporary issues unit, my 10th grade world history students delved into the topic of genocide, using the Israel-Hamas conflict as a focal point. We provided a historical overview of the longstanding tensions between Israel and Palestine, emphasizing the grave concerns of the Palestinian people. This led to a discussion on how the current war can be classified as a genocide due to the systematic and widespread violence targeting innocent men, women, and children who are unable to escape and seek refuge amidst brutal attacks.

We also highlighted the tragic events of October 2023 on Israel, examining the extensive harm and loss of life that ensued. This context set the stage for exploring the broader implications and human rights violations associated with the conflict.

In addition, we examined the wave of student protests across various college campuses in the United States, analyzing how institutions were responding to these demonstrations. The students were then tasked with formulating questions about the war and the protests, fostering a dynamic and insightful discussion.

The Teaching the Seeds of Violence in Palestine-Israel lesson not only deepened their understanding of these complex issues but also encouraged critical thinking and engagement with contemporary global and local events. The discussions were instrumental in providing feedback and generating diverse perspectives on these challenging topics.

It can be hard to know how to address upsetting current events and to know when to pause and take a break from the regularly scheduled school curriculum. I turned to the Zinn Education Project when I realized that I needed to address the current conflict in the Middle East.

Throughout the Teaching the Seeds of Violence in Palestine-Israel lesson, students asked questions and were engaged, and have continued to follow current events about Palestine and Israel on their own since we discussed this in class.

Add your feedback on this new lesson. Let us know how it worked, student insights, classroom stories, and suggested edits or additions. You will receive people’s history books in appreciation for your time.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn