By Norm Diamond

Today’s Occupy movement is a reminder that throughout U.S. history a major engine of change has been grassroots organizing and solidarity. As an old Industrial Workers of the World song goes:

An injury to one, we say’s an injury to all,

United we’re unbeatable, divided we must fall.

—“Dublin Dan” Liston, The Portland Revolution

Major history textbooks, however, downplay the role of ordinary people in shaping events, especially those who formed labor unions and used the strike to assert their rights. One of the most significant strikes in U.S. history occurred exactly 100 years ago, in the Lawrence, Mass. textile mills, and yet it merits barely a mention in the most widely used U.S. history textbooks.

It was known as the Bread and Roses strike because underlying the demand for adequate wages (bread) was a demand for dignity on the job and in life more generally (roses). People sang:

No more the drudge and idler – ten that toil where one reposes,

But a sharing of life’s glories: Bread and roses! Bread and roses!

—James Oppenheim, Bread and Roses

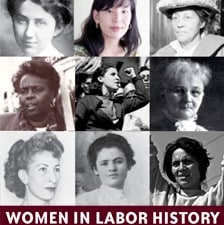

Unions and bosses alike thought the workers impossible to organize. Mostly unskilled, a majority of them young women, kept apart by more than a dozen languages, millworkers were both vanguard and victims of the new U.S. industrialization. Lawrence, with the largest and most modern textile mills in the world and more than 30,000 workers, was the epicenter and symbol of the system. The textile industry was the first to use new sources of power to drive its machines. It was the leader in subdividing jobs into limited, repetitive movements, making workers interchangeable and replaceable.

Lawrence woolen mill workers. Source: Lawrence History Center.

Workers would no longer have specialized crafts or even know all the processes that went into a product. Posters and postcards showing happy mill hands leaving work with smiles and sacks of gold enticed hundreds of thousands from poor areas of Europe. With a surplus of workers desperate for jobs, the mills drove down wages and sped up the work.

Textile millowners deliberately kept workers divided. In some mills, they placed workers together who spoke different languages and were unable to communicate. In others they allocated work by ethnicities and gave particular jobs only to Lithuanians, others to French-Canadians, others exclusively to Irish. Supervisors used ethnic and racial slurs and sexual harassment as intentional means of control.

Workers lived in fetid, crowded tenements. Working nine- and ten-hour days, six days a week, their usual main meal was little more than bread and molasses. The drinking water inside the mills was foul; supervisors developed a lucrative sideline selling water that could actually be drunk. Life expectancy for millworkers was 22 years less than for non-millworker residents of Lawrence.

Vida Dutton Scudder, professor at Wellesley College who spoke at one of the strikers’ rallies, said, “If the women of this country knew how cloth was made in Lawrence and at what price of human life they would never buy another yard.”

Vida Dutton Scudder, professor at Wellesley College who spoke at one of the strikers’ rallies, said, “If the women of this country knew how cloth was made in Lawrence and at what price of human life they would never buy another yard.”

Until this strike, Congress was indifferent to working conditions. When individual states attempted regulation, companies threatened to move. There was a race to the bottom reminiscent of the twenty first century, with competition between states for which would offer companies the best deal, the least oversight.

Companies claimed they could not act to improve conditions on their own. Any such action would put them at a competitive disadvantage. The responsibility, their spokespeople said, was not theirs. It was that of the economic system that bound them together and that produced all the marvels of modern life.

The Strike Begins

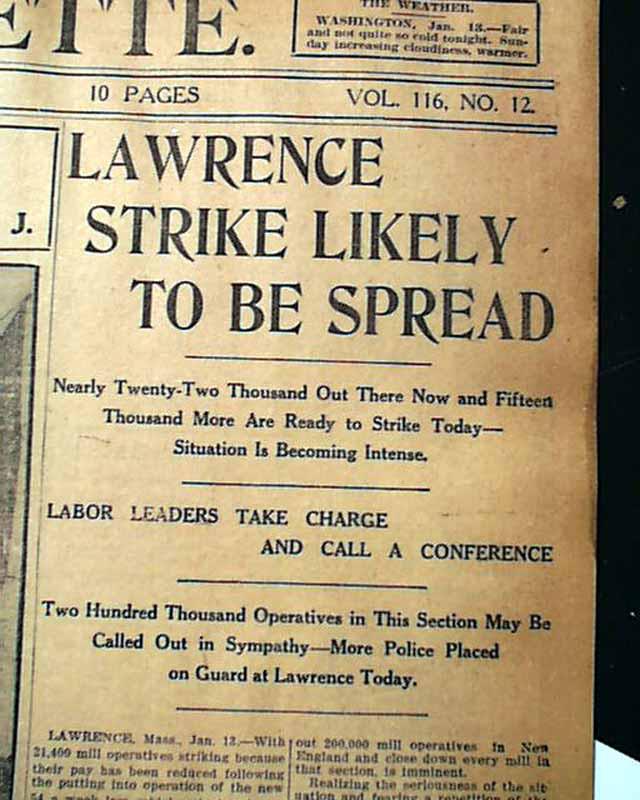

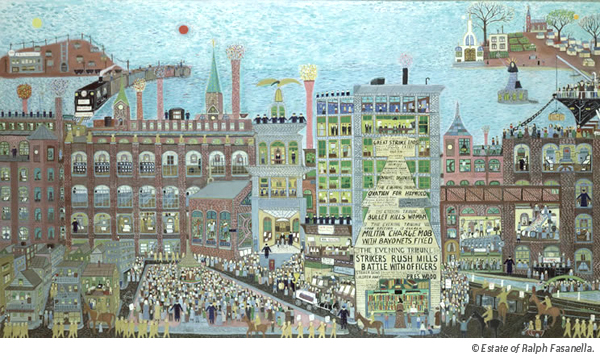

On January 12, 1912 the owners in all the companies suddenly cut workers’ pay. To the surprise of the mill owners, 23,000 workers went on strike. They set up communal kitchens and created a committee structure responsible to daily mass meetings that took place in each of the ethnic constituencies. They also put out a call for help and the Industrial Workers of the World responded.

On January 12, 1912 the owners in all the companies suddenly cut workers’ pay. To the surprise of the mill owners, 23,000 workers went on strike. They set up communal kitchens and created a committee structure responsible to daily mass meetings that took place in each of the ethnic constituencies. They also put out a call for help and the Industrial Workers of the World responded.

Unlike the American Federation of Labor which organized only skilled, white, male workers and divided them into different unions by craft (spinners, weavers, loom repairmen), the IWW was all-inclusive. They organized all workers, female and male, skilled and unskilled, all races together. The AFL called this vision un-American and made common cause with the owners in trying to undermine the strike.

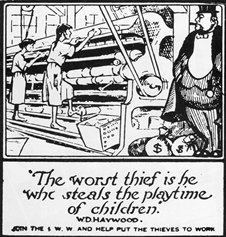

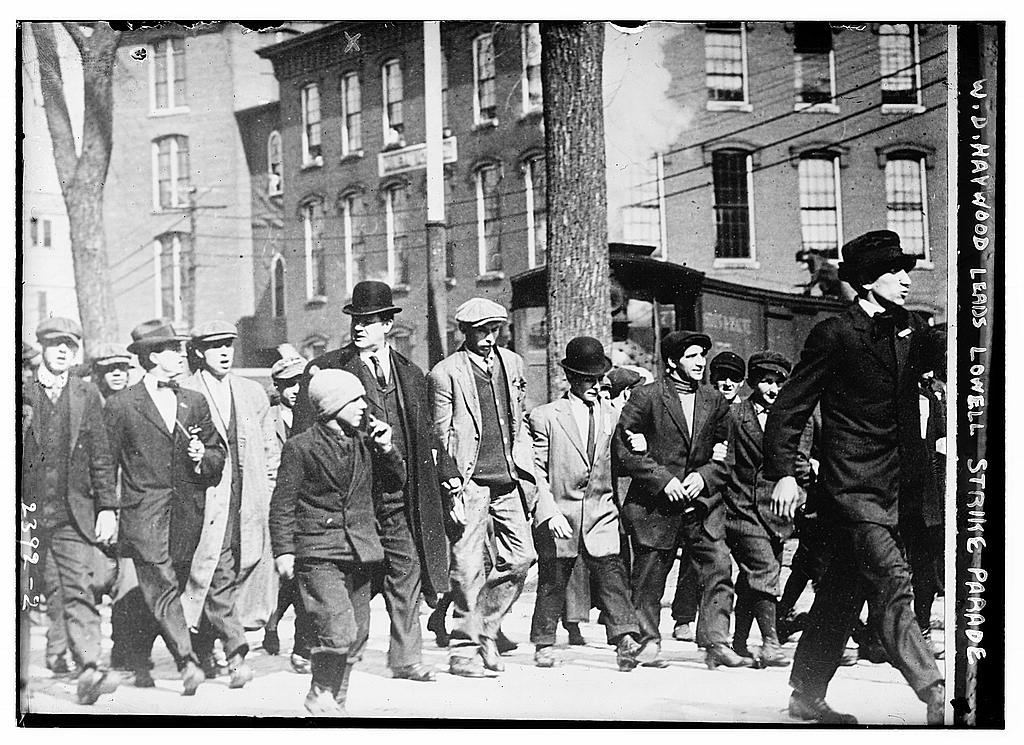

The IWW had contacts across the country and were able to mobilize support that kept the soup kitchens going and encouraged sympathetic press coverage outside Lawrence. Their leaders, Joe Ettor, Big Bill Haywood and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, chaired the mass meetings. Recognizing the importance of public sympathy, they urged non-violence among the strikers. “We’ll win this strike by keeping our hands in our pockets” was one of their oft-repeated slogans.

The IWW had contacts across the country and were able to mobilize support that kept the soup kitchens going and encouraged sympathetic press coverage outside Lawrence. Their leaders, Joe Ettor, Big Bill Haywood and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, chaired the mass meetings. Recognizing the importance of public sympathy, they urged non-violence among the strikers. “We’ll win this strike by keeping our hands in our pockets” was one of their oft-repeated slogans.

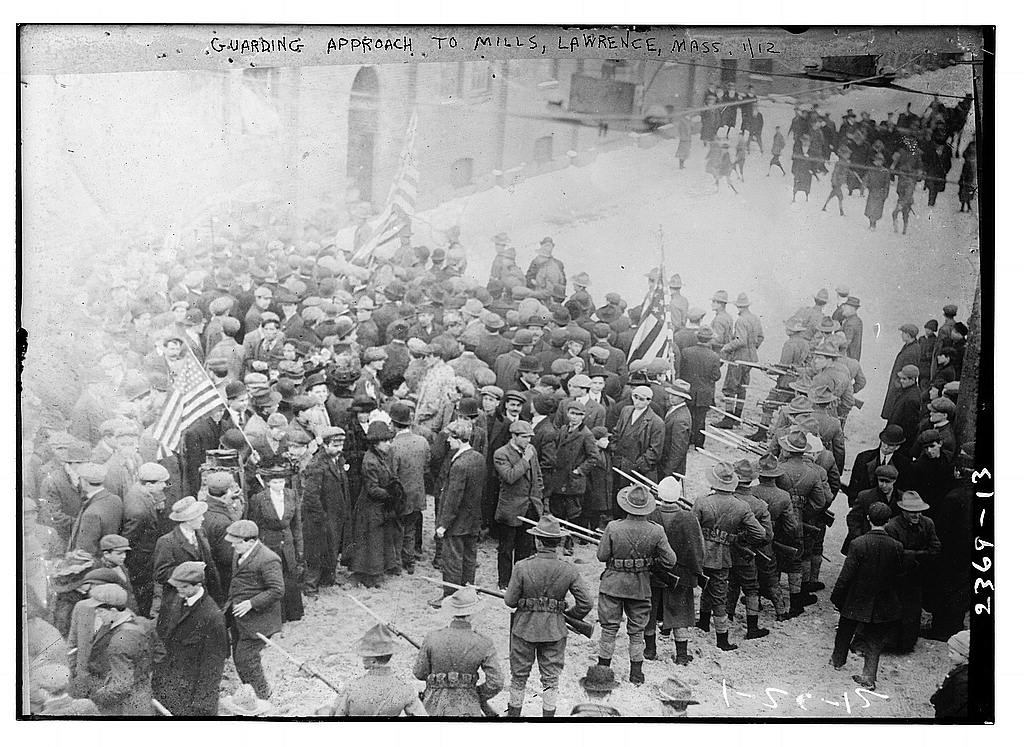

When conditions became especially difficult, with food and heating fuel scarce and attacks by thugs and the state militia increasing, the IWW sent some of the most vulnerable children temporarily to families in New York and other cities. The first two children’s brigades generated so much publicity and support that the next time an exodus was planned, Lawrence police assaulted both children and mothers in the train station.

In the beginning, men led the strike committees as well as the picketing and demonstrations. As the strike wore on, some of that early leadership faltered while women’s participation and confidence grew. Sometimes having to overcome resistance from their own husbands and fathers, women came out of the kitchens and joined strategy discussions, chaired committees and took the lead in picketing.

The Lawrence strikers faced many kinds of resistance, including a barricade of armed militia surrounding the textile mills. Jan. 1912. Source: Library of Congress.

Songs Became a Common Language

And they sang, women and men alike. Songs became a common language, the means of uplifting their spirits and forging solidarity. For those who couldn’t read, singing was political education, a way of learning about the world and putting their own struggles in a larger context.

They took familiar melodies and rewrote the words to reflect the broadest themes: “Solidarity Forever,” “We Have Fed You All For A Thousand Years.” They opened and closed their meetings with songs and marched through the streets singing. Bernice Johnson Reagon called songs of the Civil Rights Movement “the language that focused the energy of the people who filled the streets,” and it was true in Lawrence also.

Big Bill Haywood leads Lowell strike parade. Source: Library of Congress.

Fully half the workforce, about 14,000 mill workers, held firm for nine and a half weeks of repression, cold and hunger, and won their demands. They gained a raise in pay, with the largest increases for the lowest paid workers; a higher rate for working overtime; and a fairer system for calculating wages. After one last joyous march, they went back to work on March 18.

They won because the mills couldn’t function with so many workers showing no signs of coming back. The bosses had been running the machines loudly to give the impression that work was back to normal, but it was all for show. The strike had stopped production flat. They won also because they forced Congressional hearings and focused national outrage on living and working conditions and child labor. And they won because wool industry profits were based on a tariff against foreign competitors, and the renewal of the tariff was vulnerable to that public outrage. Most of all, they won because of their own solidarity.

Their victory led to a new union in Lawrence, dedicated to organizing all textile workers, whatever their gender, skill level or country of origin. It also led to strikes and victories in textile towns all over the country and a new sense of mission in the labor movement. As T-Bone Slim, an IWW member later said, “Wherever you find injustice, the proper form of politeness is attack.”

Legacy Today

Unfortunately, there is a final lesson the Bread and Roses strike teaches: Corporate producers of school curricula are not interested in the collective efforts of ordinary people to better their lives. A recent survey of middle and high school American history textbooks conducted by the Zinn Education Project turned up barely any that even mention Lawrence. Those few that do have major distortions. One text, for instance, highlights the role of the Mass. governor in ending the strike, but fails to mention that the governor was a big millowner himself, and makes no mention of the strikers’ organization, sacrifices and perseverance.

In this time of renewed activism, it is important to revisit this country’s rich history of social movements, labor struggle and solidarity.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

© 2012 The Zinn Education ProjectThe Zinn Education Project, a project of Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn