Mary Beth Tinker (right), brother, and mother.

Mary Beth Tinker was a 13-year-old junior high school student in December 1965 when she and a group of students decided to wear black armbands to school to protest the war in Vietnam. The school board got wind of the protest and passed a preemptive ban. When Mary Beth arrived at school on December 16, she was asked to remove the armband. When she refused, she was sent home.

Four other students were suspended, including her brother John Tinker and Chris Eckhardt. The students were told they could not return to school until they agreed to remove their armbands. The students returned to school after the Christmas break without armbands, but in protest wore black clothing for the remainder of the school year.

Mary Beth Tinker (with Kevin Zeese) reading at the dedication of the Zinn Room in Hyattsville, Maryland, September, 2011. Photo by Jack Gordon.

Represented by the ACLU, the students and their families embarked on a four-year court battle that culminated in the landmark Supreme Court decision: Tinker v. Des Moines. On February 24, 1969 the Court ruled 7-2 that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

The Court ruled that the First Amendment applied to public schools, and school officials could not censor student speech unless it disrupted the educational process. Because wearing a black armband was not disruptive, the Court held that the First Amendment protected the right of students to wear one.

Description is from the ACLU.

Note from the Zinn Education Project: Tinker v. Des Moines is famous and featured in most U.S. history textbooks. Less known is that it is based on a Mississippi court case Burnside v. Byars, that is not in the textbooks, even though the Mississippi case set the precedent. Here is a description of the Burnside case from the First Amendment Center:

Note from the Zinn Education Project: Tinker v. Des Moines is famous and featured in most U.S. history textbooks. Less known is that it is based on a Mississippi court case Burnside v. Byars, that is not in the textbooks, even though the Mississippi case set the precedent. Here is a description of the Burnside case from the First Amendment Center:

Burnside v. Byars, 363 F.2d 744 (5th Cir. 1966)

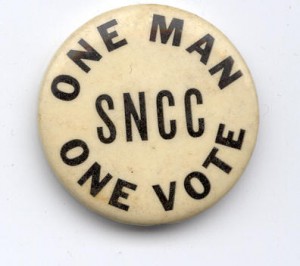

Facts: A group of public school students at an all-black school in Philadelphia, Mississippi wore “freedom buttons” to school to protest racial segregation in the state. The school principal ordered the students to remove the buttons. The principal believed that the buttons would “cause commotion” and “disturb the school program.” When several students continued to wear the buttons, the principal suspended them for a week.

Issue: Whether school officials could suspend students for wearing “freedom buttons.”

Holding: By a 3-0 vote, a Fifth Circuit panel held that school officials could not prohibit the wearing of the “freedom buttons” because there was no evidence that the buttons would have caused a substantial disruption.

Reasoning: The record demonstrates that there was no commotion or disruption caused by the wearing of the buttons. “The record indicates only a showing of mild curiosity on the part of the other school children over the presence of some 30 or 40 children wearing such insignia.” Because the wearing of buttons did not cause a disruption, the regulation preventing the wearing of such buttons is “arbitrary and unreasonable.”

Majority: “But with all of this in mind we must also emphasize that school officials cannot ignore expressions of feelings with which they do not wish to contend. They cannot infringe on their students’ right to free and unrestricted expression as guaranteed to them under the First Amendment to the Constitution, where the exercise of such rights in the school buildings and schoolrooms do not materially and substantially interfere with the requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school.” (Judge Walter Gewin)

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn