By E. R. Bills

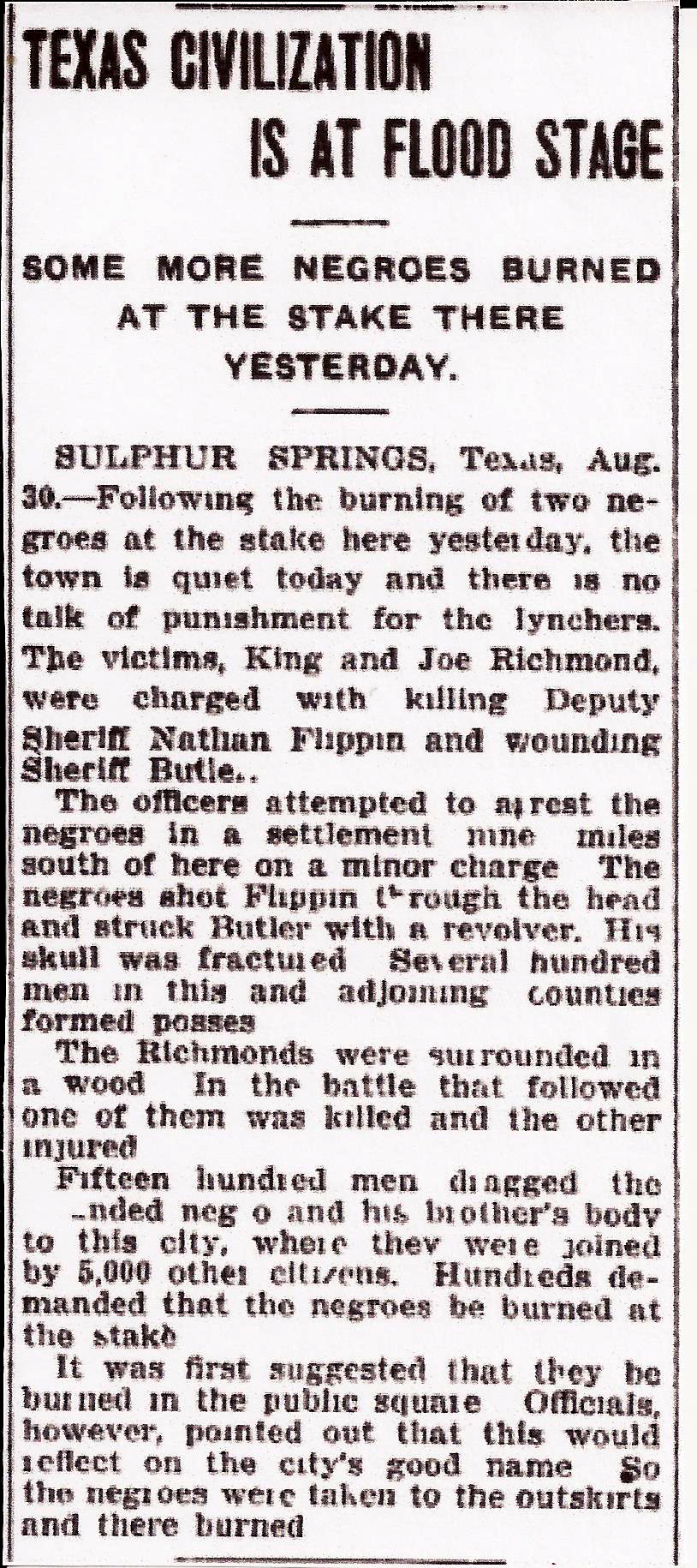

On August 29, 1915, two African American men were burned at the stake in Sulphur Springs, Texas.

Early on August 29, Hopkins County Sheriff J. B. Butler and Deputy Sheriff Nathan Asa Flippin traveled to a small community known as Tazewell (nine miles south of Sulphur Springs) and paid a visit to the Richmonds, apparently intent on arresting King for a reportedly minor offense. King allegedly resisted arrest and his brother Joe came to his defense. In the gun battle that ensued, Deputy Flippin was shot in the forehead and Sheriff Butler was shot in the head and arm. Flippin died instantly and Butler was left disabled.

News of the killing spread rapidly and most of the adult white male population of Hopkins County was searching for the Richmonds within hours. They found the brothers in a nearby wood and surrounded them. The brothers gave up, but the white mob fired on them anyway; Joe was killed and King was wounded. The mob subsequently transported them to Sulphur Springs.

Hundreds of citizens were gathered at the town square when King and his brother’s body were delivered, and the general consensus was that they should be burned at the stake. Due process was never considered. The torch was a popular option for Black suspects and/or criminals whom white folks accused of especially heinous crimes. A noose that might be utilized to legally hang white criminals was regularly deemed too good or too tame for their Black counterparts, even if their crimes were the same.

In the end, the Richmond brothers were doused with coal oil and burned at the stake at Buford Park on the outskirts of town. A mob of 1500 Sulphur Springs citizens watched on and today a public pavilion and a castle-themed playground occupy the site of the atrocity.

From 1891 to 1922, Texans burned an average of one person of color at the stake a year for three decades. These burnings typically featured carnival atmospheres with thousands in attendance (including women and children) who later described the spectacles as jovial “barbecues” or “roasts” and, in some cases, commemorated the events with “lynching” postcards. Dozens of Black men met their ends in a cocoon of hellish flame, many innocent and several simply in the wrong place at the wrong time.

In 1893, the phenomena would lead the Boston Post to proclaim that civilization was “Seemingly Dead in Texas” and, in recent years, scholar Walter L. Buenger noted that “white Texans specialized in burning Blacks alive” from the Reconstruction era to 1922. As late as 1930, a sitting governor was forced to declare two weeks of martial law in one Texas city to suppress an especially egregious white mob.

This stark history is documented in author E. R. Bills’ exploration of racial injustice and terrorism in the U.S., titled Black Holocaust: The Paris Horror and a Legacy of Texas Terror (Eakin Press, 2015). Bills is a Texas author and historian who also wrote The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas. Read about the Slocum Massacre.

Learn More

Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, released in 2015 by the Equal Justice Initiative, makes the case that “lynching of African Americans was terrorism, a widely supported phenomenon used to enforce racial subordination and segregation.” In the introduction to the report, the authors explain,

Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, released in 2015 by the Equal Justice Initiative, makes the case that “lynching of African Americans was terrorism, a widely supported phenomenon used to enforce racial subordination and segregation.” In the introduction to the report, the authors explain,

Lynchings were violent and public events that traumatized black people throughout the country and were largely tolerated by state and federal officials. This was not “frontier justice” carried out by a few marginalized vigilantes or extremists. Instead, many African Americans who were never accused of any crime were tortured and murdered in front of picnicking spectators (including elected officials and prominent citizens) for bumping into a white person, or wearing their military uniforms after World War I, or not using the appropriate title when addressing a white person.

Lynching profoundly impacted race relations in this country and shaped the contemporary geographic, political, social, and economic conditions of African Americans. Most importantly, lynching reinforced a narrative of racial difference and a legacy of racial inequality that is readily apparent in our criminal justice system today. Mass incarceration, racially biased capital punishment, excessive sentencing, disproportionate sentencing of racial minorities, and police abuse of people of color reveal problems in American society that were shaped by the terror era.

Research on mass violence, trauma, and transitional justice underscores the urgent need to engage in public conversations about racial history that begin a process of truth and reconciliation in this country.

“We cannot heal the deep wounds inflicted during the era of racial terrorism until we tell the truth about it,” said EJI Director Bryan Stevenson. “The geographic, political, economic, and social consequences of decades of terror lynchings can still be seen in many communities today and the damage created by lynching needs to be confronted and discussed. Only then can we meaningfully address the contemporary problems that are lynching’s legacy.”

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn