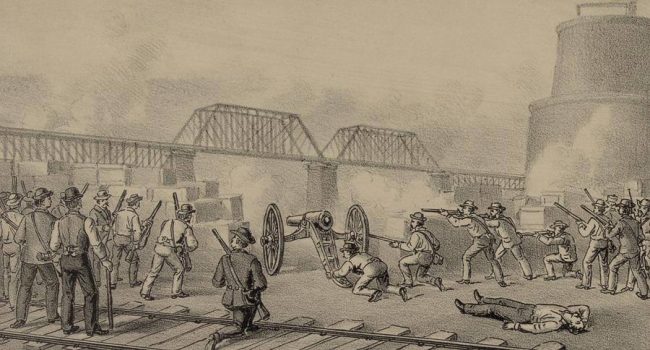

Striking workers shooting, using a canon and fireworks left over from July 4th celebrations, at the Pinkerton barges.

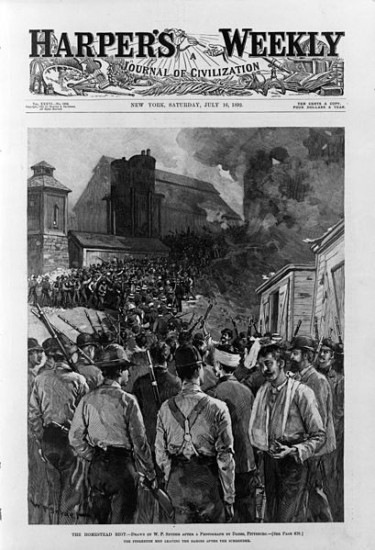

The Pinkerton men leaving the barges after the surrender. Harper’s Weekly, July 16,1892. Source: WikiCommons.

On July 6, 1892, there was a major pitched battle during the Homestead Strike between the Pinkerton Detective Agency and the striking steelworkers. Carnegie Steel was engaged in an all out campaign to break the steelworkers union. As explained by Howard Zinn in Chapter 11 of A People’s History of the United States:

In early 1892, the Carnegie Steel plant at Homestead, Pennsylvania, just outside of Pittsburgh, was being managed by Henry Clay Frick while Carnegie was in Europe. Frick decided to reduce the workers’ wages and break their union. He built a fence 3 miles long and 12 feet high around the steelworks and topped it with barbed wire, adding peepholes for rifles. When the workers did not accept the pay cut, Frick laid off the entire work force. The Pinkerton detective agency was hired to protect strikebreakers.

Although only 750 of the 3,800 workers at Homestead belonged to the union, three thousand workers met in the Opera House and voted overwhelmingly to strike. The plant was on the Monongahela River, and a thousand pickets began patrolling a 10-mile stretch of the river. A committee of strikers took over the town, and the sheriff was unable to raise a posse among local people against them.

On the night of July 5, 1892, hundreds of Pinkerton guards boarded barges 5 miles down the river from Homestead and moved toward the plant, where ten thousand strikers and sympathizers waited. The crowd warned the Pinkertons not to step off the barge. A striker lay down on the gangplank, and when a Pinkerton man tried to shove him aside, he fired, wounding the detective in the thigh. In the gunfire that followed on both sides, seven workers were killed.

The Pinkertons had to retreat onto the barges. They were attacked from all sides, voted to surrender, and then were beaten by the enraged crowd. There were dead on both sides. For the next several days the strikers were in command of the area. Now the state went into action: the governor brought in the militia, armed with the latest rifles and Gatling guns, to protect the import of strikebreakers.

Strike leaders were charged with murder; 160 other strikers were tried for other crimes. All were acquitted by friendly juries. The entire Strike Committee was then arrested for treason against the state, but no jury would convict them. The strike held for four months, but the plant was producing steel with strikebreakers who were brought in, often in locked trains, not knowing their destination, not knowing a strike was on. The strikers, with no resources left, agreed to return to work, their leaders blacklisted.

One reason for the defeat was that the strike was confined to Homestead, and other plants of Carnegie kept working. Some blast furnace workers did strike, but they were quickly defeated, and the pig iron from those furnaces was then used at Homestead. The defeat kept unionization from the Carnegie plants well into the twentieth century, and the workers took wage cuts and increases in hours without organized resistance.

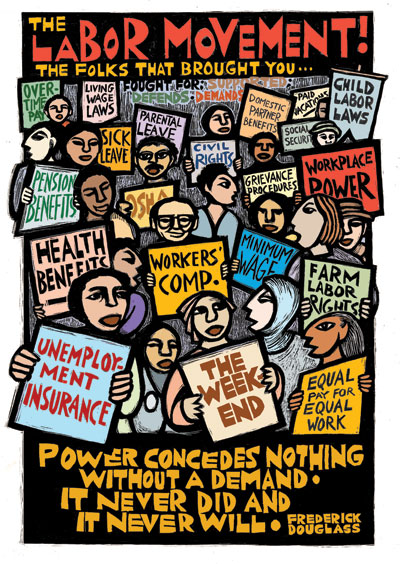

Students are often skeptical about the possibility of people genuinely working together when at least their short-term interests appear in conflict. The Homestead Strike offers a historical test case that may challenge their skepticism. Use the free downloadable lesson, The Homestead Strike, by Bill Bigelow and Norm Diamond.

Learn more about the strike in a chapter from Strike! by Jeremy Brecher. And check out “Homestead,” a song by Joe DeFilippo, a Baltimore songwriter and retired social studies teacher. Performed by the R. J. Phillips Band.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn