The American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) launched a great postal campaign in 1835 to flood the South with abolitionist literature.

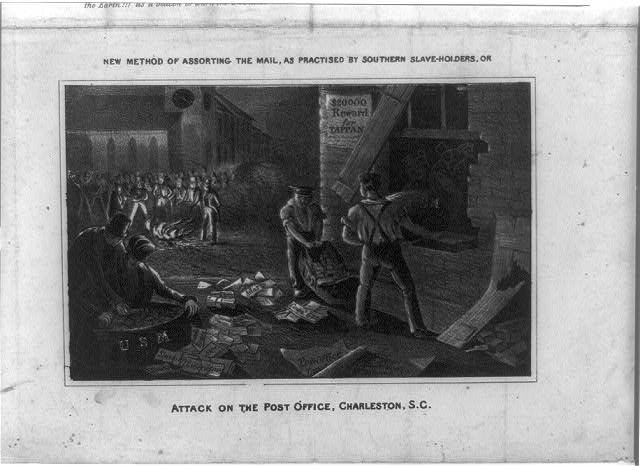

White supremacists responded by seizing and destroying the mail. One example of this was on July 29, 1835, in Charleston, South Carolina, when 3,000 people gathered in Post Office Square to destroy anti-slavery materials and burn three abolitionists in effigy.

Read a detailed description below in an excerpt from “The 1835 Anti-Abolition Meetings in the South: A New Look at the Controversy over the Abolition Postal Campaign” by Susan Wyly-Jones (Civil War History, Volume 47, Number 4, December 2001, pp. 289-309).

Sometime after ten o’clock on the evening of Wednesday, July 29, 1835, a local vigilance society known as the Lynch Men assembled at the Exchange building in the heart of Charleston, South Carolina. The group proceeded to the post office, where with “coolness and deliberation” they entered by prying open one of its windows.

Passing over the large bags of mail containing ordinary letters and business transactions, the small band headed straight for a sack carefully separated from the rest in the postmaster’s office. The sack contained abolitionist newspapers and journals published by the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) in New York; they had arrived in the regular mail packet earlier in the day. The burglars took the bag and left the post office undetected. The following evening, the Lynch Men publicly burned the fruits of their late night raid, along with effigies of three leading abolitionists, in a large bonfire on the parade grounds adjacent to the Citadel, Charleston’s military academy. A boisterous crowd of nearly two thousand, roughly one-seventh of the white population of the city, witnessed the spectacle!

The bonfire capped off a day of unrest in the city. The trouble began that morning after the steamship Columbia arrived in Charleston “overflowing with incendiary tracts,” according to a local newspaper.

Word of the abolition mailings spread quickly throughout the morning as the unwilling recipients angrily returned the publications once they discovered their content. By Wednesday afternoon, Charleston postmaster Alfred Huger had already been confronted by one vigilance committee called the South Carolina Association, whose members included some of the wealthiest and most powerful men in the city. Feeling bound by his obligations as a Federal officer to protect the sanctity of the mails, Huger refused to turn over the offending publications to the association, but he agreed to detain the abolition mailings in his office until he received instructions from Postmaster General Amos Kendall. This compromise failed to quell the ire of the public, however, and by early evening an angry mob of two or three hundred — “the most respectable men of all parties,” as Huger later described them — had assembled at the post office to demand the surrender of the “incendiary” publications.

The crowd had to be dispersed by a lieutenant of the City Guard. Later that night, the Lynch Men returned to execute the burglary.

. . .Huger wrote frantically for aid to Kendall and to the postmaster of New York, Samuel L. Gouverneur. “It is impossible to restrain the universal indignation that pervades all Classes,” he warned; only a “military force greater than the Undivided population of Charleston” could have prevented the determined citizenry from seizing the abolition papers.

Huger vowed to continue to perform his official duties “until I am overpower’d” but admitted that he could not guarantee the safety of the mail. “How long one Man can sustain himself in this position, you can easily determine.” Gouverneur was sympathetic to Huger’s concerns, for he promised not to transmit any abolitionist papers until word arrived from Washington. In the meantime, Huger arranged for a guard to escort the incoming mail safely from the Charleston steamboat landing to the post office. There, any “incendiary” publications would be purged from the mails and quarantined in the postmaster’s office. After a tense week of harboring a growing pile of abolitionist papers, Huger’s actions received tacit sanction from the Jackson administration. In a pair of public letters to Huger and Gouverneur, Postmaster General Kendall refused to rebuke the Charleston postmaster for seizing the abolitionist publications. While postal officers had an obligation to follow the laws, Kendall argued, they had a “higher” obligation to their communities, and “if the former be perverted to destroy the latter, it is patriotism to disregard them.”

Like Jefferson’s famed firebell in the night, the abolitionists’ postal campaign of 1835 re-ignited the slavery controversy in the South. . . .

The Charleston meeting was merely one of more than a hundred and fifty antiabolition meetings held across the South from August through December 1835, occurring in every slaveholding state except for Kentucky and Delaware.* Because the proceedings of these public convocations were often buried in local newspapers,

they have largely escaped the notice of historians, yet they provide a rare “grassroots” perspective on Southern attitudes toward slavery and abolition.

The geographic distribution of the meetings demonstrates that the intensity of reaction to the abolitionists varied significantly within the South, an issue that has received little attention from historians. An analysis of the location of the meetings and the kind of men who participated in them offers an economic and social profile of anti-abolition sentiment. Led by community elites but attended by whites of all classes, the meetings functioned as ritualistic displays of white unity and the communal means of enforcing race control. They reflected Southern fears both of outside intrusion and of vulnerabilities within the slave system, such as lax enforcement of the slave code, the corrupting influence of free blacks and poor whites, and the complacency of planters. To a greater degree than the incidents of mob violence, the meetings provide a revealing illustration of ways in which Southerners strove to unite the region socially and politically behind its domestic institutions. Continue reading.

Watch a short excerpt from the PBS documentary, The Abolitionists on the burning of the abolitionist literature in Charleston, South Carolina.

Read a detailed history of African Americans in the U.S. Postal Service from the 19th century and the 20th century by the U.S.P.S. historian. (From Postal People at U.S.P.S.)

Find resources below to teach about the Abolition Movement.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn