We are pleased to present this essay by historian Robyn Spencer written for the “Howard as Historian” panel at the Zinn Symposium held April 24, 2014 at NYU.

By Robyn Spencer

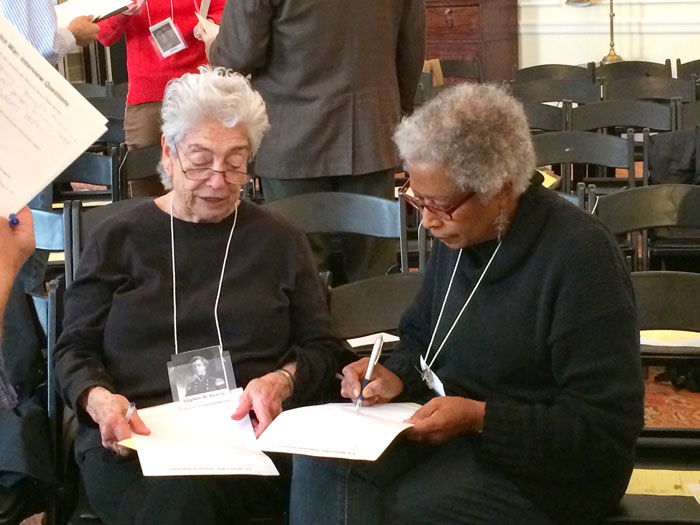

Robyn Spencer with Alice Walker. Both spoke about Zinn’s impact on their lives.

In 1989, one of my history professors at SUNY Binghamton assigned A People’s History of the United States in our class and nothing has ever been the same. 1989. Pinochet. Robin Givens and Mike Tyson. George H. W. Bush and Shabba Ranks. The Golden Girls and Iran-Contra. This was my 19-year-old world. Everything was heightened. It was heightened not just because I was 19 but also because upstate New York felt like a world away from Black Brooklyn—in all of its ungentrified rough around the middle, and the edges, glory days. Upstate I learned that the KKK existed not only in books but in reality as well. For the first time, I encountered a set of rigid and generally low expectations about my intellectual potential. I joined my first student and political organizations and tried on Marxism and feminism. I moved from the doctor/lawyer track that most first-generation college students choose by default to a history major. I gravitated toward U.S. foreign policy.

Amidst the headlines and pop culture in 1989, “A People’s History” became Spencer’s “oxygen.”

Into this context came Howard Zinn’s A People’s History. It introduced perspective into the learning of history and jettisoned all pretense of objectivity. It was the first bottom-up history that I understood as such. The people I encountered in Zinn’s book were endlessly fascinating to me. Learning about them sent me on a detour to social history and social movements that I am still on decades later. It made me not just think about history but it also made the historian’s craft visible as labor. The author of the book was a “real” person who made choices, engaged in debates with other authors, and continued to act and do in the present as an outgrowth of their perspective in the past. A People’s History was probably my first understanding of historiography and activist scholarship. It became my mirror, my shield. It was oxygen.

I decided to apply to graduate school in 1991 and when I encountered the question of what historical work I’d read that I most admired, A People’s History was my response.

In one admissions essay I wrote that “Zinn looks at issues such as what the New Deal meant, not to President Roosevelt but to Harlem Blacks, what did the 19th century rise in industrialism mean to factory workers, to later immigrants in tenement houses.

I complained that “I have yet to see an historical work called A State’s History of the United States or A Male History of the United States but that is often just what is presented.”

I pointed out that “He does not make the ‘victims’ into martyrs or saints. He does not condemn or chastise, rather he just explains and clarifies. As he says on page 10 of his text, ‘The cry of the poor is not always just, but if you don’t listen to it, you will never know what justice is.’”

I pointed out that “He does not make the ‘victims’ into martyrs or saints. He does not condemn or chastise, rather he just explains and clarifies. As he says on page 10 of his text, ‘The cry of the poor is not always just, but if you don’t listen to it, you will never know what justice is.’”

In this essay are the hidden contours of my second book project. I listed some of the insight I had gained from A People’s History, sharing my shock, disappointment, and anger when I learned about Nixon’s bombing of Cambodia in the post-Vietnam era, LBJ and the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, and the realities of FBI surveillance of civil rights leaders.

I also spoke about my times: “Zinn’s work is a call to arms for my generation of historians. As the 1980s come under increasing historical scrutiny, Zinn warns against omission or hasty treatment of events such as the Iran-Contra scandal and the bombing of Libya. This is the essential directive of Zinn because if history repeats itself (as is often true) isn’t it crucial to know all of what happened before to better judge what is happening now?”

As a future social historian Zinn’s book really opened my eyes to a lot of traditionally underrepresented groups in American history. It is mainly my reading of Zinn that motivated me to investigate Native Americans in the research paper that I have included as a further writing sample. Zinn’s work takes values that are held very dear in America and turns them upside down. As such, no matter if the reader agrees or disagrees with Zinn, he or she never walks away ambivalent. A People’s History of the United States is clearly on the cutting edge of historical scholarship.

As a future social historian Zinn’s book really opened my eyes to a lot of traditionally underrepresented groups in American history. It is mainly my reading of Zinn that motivated me to investigate Native Americans in the research paper that I have included as a further writing sample. Zinn’s work takes values that are held very dear in America and turns them upside down. As such, no matter if the reader agrees or disagrees with Zinn, he or she never walks away ambivalent. A People’s History of the United States is clearly on the cutting edge of historical scholarship.

This impassioned plea was so very unselfconscious. Upon being accepted to Columbia University, however, it was a different story. My U.S. historiography class professor would occasionally bring up A People’s History of the United States as an example of how not to do history, how not to write, how not to be an intellectual, and how not to move through the profession. This was different from how we treated other books. We were reading about burning women at the stake and happy-slave theories, expected to develop the skills of placing works into context and distilling arguments. I would sit there with my brows furrowed feeling erased; wondering if I had gotten something wrong, too intimidated to respond. My theme song might have been: If loving Zinn is wrong, I don’t wanna be right.

And thus began a decade of alienation and agitation. The ’90s were peppered with the stories of racist violence against Rodney King, Abner Louima, Amadou Diallo, and Yusef Hawkins at home, and the struggle to unseat white supremacy in South Africa. Through it all, I nurtured my commitment to “a people’s history,” which I took to mean a history that was bottom up, that centered marginalized voices, and sought to change not just the historiography but also the world. I never returned to the pages of A People’s History of the United States. Instead I found myself more interested in learning about Howard Zinn’s life, work with SNCC, and support for Palestine Liberation. As a professional historian, still deeply connected to now gentrifying Brooklyn, teaching students in the poorest borough of New York, the Bronx, I find myself more committed to the paradigm shift A People’s History continues to demand.

Even in the face of social history, women’s history, Black history, gender studies, etc. gaining a foothold in the academy, many people still find themselves nobody on the pages of the history books they encounter in K–12. Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano’s poem “Los Nadies” is appropriate here. I’m just going to read the last part of the poem.

The nobodies: nobody’s children, owners of nothing. The nobodies: the no ones, the nobodied, running like rabbits, dying through life, screwed every which way.

Who are not, but could be.

Who don’t speak languages, but dialects.

Who don’t have religions, but superstitions.

Who don’t create art, but handicrafts.

Who don’t have culture, but folklore.

Who are not human beings, but human resources.

Who do not have faces, but arms.

Who do not have names, but numbers.

Who do not appear in the history of the world, but in the police blotter of the local paper.

The nobodies, who are not worth the bullet that kills them.

Oscar Grant, Trayvon Martin, Renisha McBride, and Jordan Davis. “The roll call of names is a drum of despair and a call to action.”

This is one of those poems that stops you dead in your tracks. For those of us who conduct retail through bulletproof glass, who have seen the inside of prisons or prison waiting rooms, who live in neighborhoods where gunshots ring out at night, who are occupied, profiled, and brutalized, women and queers and working class and immigrant and Black . . . our names, our faces, our art, our religion, and our history still appears nowhere. This not hyperbole. Oscar Grant, Trayvon Martin, Renisha McBride, Jordan Davis . . . the roll call of names is a drum of despair and a call to action. History can change the world by providing a mirror, a challenge, armor, and oxygen.

Every year students from the Bronx’s most challenged schools pour into my classroom. Most of them couldn’t name six women in history to save their lives. They know that Lincoln freed the slaves, the west was won, Booker T. Washington was a major leader, Rosa Parks was tired, and Malcolm X is intriguing but controversial. This is “still” how it is. It is very much K–16, when at the college level educators are responding to epic holes left by K–12. I introduce a varied cast of historical characters to them and they also meet Howard Zinn. Usually, he is presenting history to the public in a variety of YouTube videos. They get excited by him because he doesn’t look or act like the historians we usually watch. He is a bit older, vibrant, and a lot more opinionated. He talks about things he has done, experienced more than an engagement with the archives. They get quite a lot out of it.

In his memoir, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, Zinn said he’d like to be remembered “for introducing a different way of thinking about the world, about war, about human rights, about equality,” and to be known as “somebody who gave people a feeling of hope and power that they didn’t have before.”

In his memoir, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, Zinn said he’d like to be remembered “for introducing a different way of thinking about the world, about war, about human rights, about equality,” and to be known as “somebody who gave people a feeling of hope and power that they didn’t have before.”

A People’s History of the United States has done this. There are many children and students of A People’s History out here. Last year, I launched an initiative that I’m calling History for the People. It’s about bringing the history of the Black freedom movement to community-based spaces. Focusing on less well-known people, especially women. And their contributions, struggles, and sacrifices. It’s a history lesson aimed at informing and empowering. It is inspired by Alice Walker’s mandate in her poem “Each One, Pull One”: “Each one, must pull one, back into the sun.” Scraping off the mud of oblivion is also the work of a historian. The first person I am focusing on is Mae Mallory, education activist, feminist, communist, proponent of self-defense, on the FBI’s most wanted list, and a Pan-Africanist.

Those of us who consider ourselves forever changed by A People’s History must be unafraid to challenge what we may see with professional eyes when we go back to the text. The complexion of the profession has altered and the subaltern is definitely speaking back. When Zinn is put into conversation with John Hope Franklin and Patricia Hill Collins and Angela Davis, there is much heat and light generated. The conversations about allyship and privilege are tough ones to have but the people demand it. As it should be.

Robyn Spencer is an assistant professor of history at Lehman College, where she teaches courses on the Black freedom movement. Her areas of research include civil rights and Black Power, urban and working-class radicalism, and gender. Her writings on the Black Panther Party have appeared in the Journal of Women’s History, Souls, Radical Teacher, and many collections of essays on the 1960s. She is completing a book on gender and the organizational evolution of the Black Panther Party in Oakland with Duke University Press; and starting a second book project on the intersections between the movement for Black liberation and the anti-Vietnam War movement.

A wonderful article that clearly reveals how important Professor Zinn was to the critical study of history as a living entity. We all should heed his lessons and his encouragement on how we should view our society and the world with eyes wide open!