This article highlights a story of international solidarity during the Reconstruction era.

By Paul Ortiz

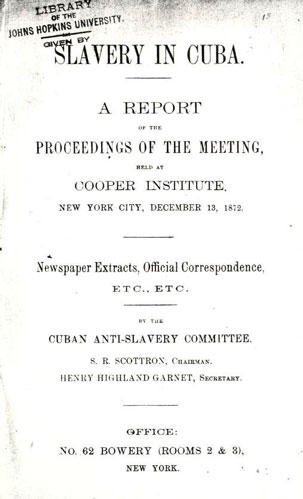

Seven years after the end of the Civil War, hundreds of African Americans in Baltimore gathered at historic Madison Street (Colored) Presbyterian Church for the purpose, “[O]f adopting measures to petition the Congress of the United States to tender the powerful mediation of this great government towards ameliorating the sad condition of a half million of our brethren now held in slavery in the island of Cuba by Spain.”[1] S.R. Scottron, noted black inventor and a co-founder of the Cuban Anti-Slavery Committee, was the evening’s keynote speaker. He urged his enthusiastic audience to remember, “They had passed through the Egyptian bondage and through the sea of blood, and having become clothed in the habiliments of freedom, knew how to sympathize with the 500,000 of their own race bowed down in Cuba.

Seven years after the end of the Civil War, hundreds of African Americans in Baltimore gathered at historic Madison Street (Colored) Presbyterian Church for the purpose, “[O]f adopting measures to petition the Congress of the United States to tender the powerful mediation of this great government towards ameliorating the sad condition of a half million of our brethren now held in slavery in the island of Cuba by Spain.”[1] S.R. Scottron, noted black inventor and a co-founder of the Cuban Anti-Slavery Committee, was the evening’s keynote speaker. He urged his enthusiastic audience to remember, “They had passed through the Egyptian bondage and through the sea of blood, and having become clothed in the habiliments of freedom, knew how to sympathize with the 500,000 of their own race bowed down in Cuba.

The Cuban patriots were opposing wrongs as galling as those which adduced the American patriots to rise up against the oppression of Great Britain.” Scottron’s advice was that African Americans should “petition the government of the United States to extend a liberal policy to the colored race in Cuba. The 800,000 votes of the colored people here would have their weight in that direction.” After Scottron concluded his speech, church deacons circulated the petition for signatures.

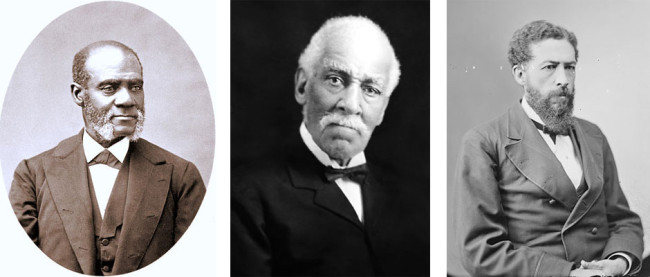

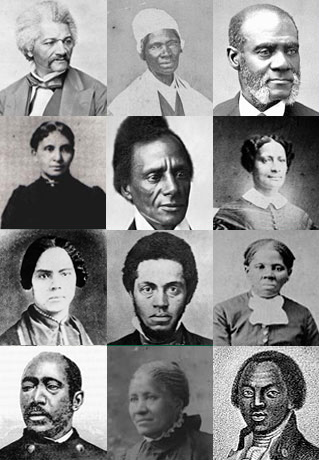

Less than a week later Scottron joined a delegation that included Rev. Henry Highland Garnet, George T. Downing, and J.M. Langston to present petitions to President Ulysses S. Grant signed by tens of thousands of African Americans and allies across the country in support of the resistance movement in Cuba.[2] African Americans demanded that the U.S. government grant belligerency status to the Cuban freedom fighters and also support the abolition of slavery on the island.

The Cuban solidarity movement was a national phenomenon with organizing activities in cities including Sacramento; San Francisco; Virginia City, NV; New Orleans; Boston; Philadelphia; New York; Washington, D.C.; and many other places.[3] Estimates of the number of signatures gathered in support of the struggle ranged from tens of thousands to as much as half a million.[4]

Rev. Henry Highland Garnet, George T. Downing, and J. M. Langston.

The Cuban solidarity movement of the 1870s provides us with new ways to think about Black History Month in the age of Black Lives Matter and global capitalism. African Americans viewed the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution not as an endpoint in the battle against slavery but just the beginning. The centerpiece of this idea, which I call emancipatory internationalism was the belief that the destiny of democracy in the United States was tied to the self-determination of workers in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Africa. African Americans built the Cuban solidarity movement by connecting the battle against white supremacy at home with the war against imperialism abroad.

In the wake of the Civil War, black conventions and church meetings urged senior abolitionists to refocus their energies on fighting for emancipation in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean. The Christian Recorder argued that the work of the anti-slavery movement was far from over: “Disband the Anti-Slavery Society when Cuba, with over half a million of slaves lies at our gates! Disband the Anti-Slavery Society when Maximilian’s government [in Mexico] may be permanent, and be made slaveholding…when Brazil still sells human flesh, and old Spain Countenances the trans-Atlantic traffic! It may be said ‘These are out of the United States.’ But these men- slaves, are our brothers.”[5] An African American correspondent in Salt Lake City, Utah, admonished the readers of The Elevator over one 4th of July weekend that: “While we are rejoicing over our national anniversary, let us not forget the patriotic sons of Cuba in the struggles for their national existence, from the misruling of the government of Spain; whose troops, brute-like and fiendish in disguise have perpetuated acts of brutalities and cruelties on the Cuban patriots; not for the first time have they disgraced her banner and civilization.”[6]

Even as they fought the Ku Klux Klan, and an increasingly hostile federal government, black political leaders in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida became heavily involved in the Cuban solidarity movement. The 1873 Convention of Colored Men in Louisiana placed the cause of the “barbarous rule of Spanish authority in Cuba,” alongside the effort to end electoral fraud and anti-black political violence in the South.[7] The Louisiana Republican Party platform advocated a national civil rights bill, and stated: “That we sympathize with the patriotic men in Cuba who fight for liberty, and that we urge upon the national Congress the early recognition of the independence of Cuba, and hereby instruct our Representatives in Congress to use their best efforts and influence to this end.”[8]

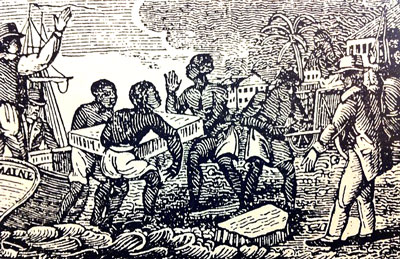

Enslaved people unloading ice in Cuba, 1832.

President Grant refused to grant belligerency status to the Cuban resistance due to the opposition of cabinet leaders and businessmen who, as one historian noted, “favored the interests of Americans who had invested in sugar and slaves and perhaps stood to lose if the revolution succeeded.”[9]

This rebuff did not stop African Americans from continuing to build the movement for Cuban solidarity. At a mass meeting held in Philadelphia in 1877, Rev. Garnet expounded on the theme that the work of slavery abolitionism was incomplete. “If the veteran abolitionists of the United States had not mustered themselves out of service,” he argued, “I believe that there would not now have been a single slave in the Island of Cuba.” Rev. Garnet continued, “We sympathize with the patriot of Cuba not simply because they are Republicans, but because their triumph will be the destruction of slavery in that land. All Europe now frowns upon Spain, because of her attitude toward human bondage. We must take our place on the broad platform of universal human rights, and plead for the brotherhood of the entire human race.” After hearing addresses in Spanish and in English, the meeting’s participants formed the American Foreign Anti-Slavery Society to address the ongoing crisis in Cuba.[10]

In a time when the United States has taken halting steps towards normalizing relations with Cuba, the Cuban solidarity movement has much to teach us. Oppressed people have long created linkages across national borders even when governments have sought to restrict contact. The architects of the Cuban solidarity movement remind us that Black History should be thought of as an international struggle for freedom. The organizers of this remarkable Reconstruction-era campaign attempted to create a kind of politics that existed generations before Malcolm X attempted, according to Cuban writer Juana Carrasco, “[T]he internationalization of the struggle of the Negro people in North America.”[11]

About the Author

About the Author

Paul Ortiz is director of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at the University of Florida. His book, An African American and Latinx History of the United States, in Beacon Press’ ReVisioning American History series explores the Cuban solidarity movement and more. Ortiz is an adviser to the Zinn Education Project Teach Reconstruction campaign.

Footnotes

Originally published on Beacon Broadside. Republished here with permission of the author.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn