Hattiesburg American

Dec. 6, 1958

MIXING

Editor, The American,

It is interesting to me that subjects which are most widely discussed are those which seem to be least understood by the public whom these discussions are designed to inform.

It would not surprise me if more words had not been spoken and written on integration and segregation in the last four years than on any other subject, especially in the South.

In our state the officials spend much of their time and perhaps much of our money trying to convince the integrationists, and reassure the segregationists, that the policy of perpetual segregation is the wisest course for us to pursue, in spite of the tremendous cost of duplication.

Somehow I feel a great sympathy for the people who truly believe that the interest of both the White and Negro people would be served best by a system of complete or partial segregation. Although I am integrationist by choice, I am a segregationist by nature, and I think most Negroes are. We prefer to be alone, but experience has taught us that if we are ever to attain the goal of first class citizenship, we must do it through a closer association with the dominant (White) group.

Now it is this “getting closer” attempt by the Negro group that has aroused too much attention throughout the world, and no doubt a temporary animosity between the two groups.

There are two schemes for the solution of the present race problem. The first, spearheaded by the National Association for the Advancement of the Colored People, and given authoritative backing by the Constitution of the United States, as interpreted by the Supreme Court in its 1954 decision says that Negroes are American citizens and are entitled to the same rights and privileges, the same opportunities and duties as any other citizens; and that the best way to secure these rights and duties on a fair and equal basis, would be to (in all things public) subject both races to identical conditions of life.

The second scheme, championed primarily by Southern States, says that Negroes are American citizens and are entitled to the same rights and privileges, the same opportunities and duties as any other citizen, and that the best way to secure these rights and duties on a fair and equal basis, would be (in all things public and private) to subject both races to different conditions of life.

As the public schools are the essential organs for general intellectual discipline, and the preparation for private life and public life service, let us superimpose the plan of separate but equal on the public school system.

It is my understanding that separate but equal means that in matters where public funds are involved every time a dollar is spent for the development of Negro students, a dollar will be spent for the development of White students, and vice versa.

This plan is to be followed through Junior college, Senior college, medical schools, law schools, divinity schools, graduated schools and all supported by public funds.

After our paralleled graduate schools, where do our parallels of separate but equal go? Are we to assume that paralleled hospitals are to be built for the two groups of doctors? Are we to build two bridges across the same stream in order to give equal opportunities to both groups of engineers? Are we to have two courts of law so as to give both groups of lawyers the same chance to demonstrate their skills; two legislatures for our politically inclined, and of course two governors?

The folly of such a conclusion is perfectly obvious. Yet, the question remains, what is to become of the doctors who are not allowed to treat their patients in public hospitals? What will the engineers do when there are no roads or bridges for them to build? How must the lawyers occupy their time when the state courts restrict their opportunities to practice? How shall young statesmen, who can’t even get their names on the ballot, ever hope to be elected to the legislature?

Segregationists whose convictions are based on reason rather than passion might agree that the most honorable and actually the only path to our goal, would be to allow integration at some level, if not on the school level, then surely on the “job” level.

In utter desperation, I can see one other possible solution to which segregationist might resort, short of integration. They could do in theory what our state now does in fact, namely, raise and educate young people for the benefit of other states. While they get richer we get poorer.

The integrationists offer a program which at first seems if not cruel at least awkward. We admit to bring two groups of people together who have different social and ethnic backgrounds presents certain adjustment problems. We should expect that and any intelligent program must allow for these adjustments.

What we request is only that in all things competitive, merit be used as a measuring stick rather than race.

We believe that for men to work together best, they must be trained together in their youth. We believe that there is more to going to school than listening to the teacher and reciting lessons. In school one learns to appreciate and respect the abilities of the other.

We say that if a man is a good doctor though his face be white as light or black as darkness let him practice his art. We believe that the best engineer should build the bridge or run the train. We believe that the most efficient secretary should get the best paying job and the greatest scholar the professorship. We believe in the dignity and brotherhood of man and the divinity and fatherhood of God, and as such men should work for the upbuilding of each other, in mutual love and respect. We believe when merit replaces race as a factor in character evaluation, the most heckling social problem of modern times will have been solved.

Thus we believe in integration on all levels from kindergarten to graduate schools; in every area of education; in government, federal, state, local; in industry from the floor sweeper to the superintendent’s office; in science from the laboratory to the testing ground.

This, I believe, is our creed. And though it is not perfect, still I had rather meet my God with this creed than with any other yet devised by human society.

Respectfully submitted,

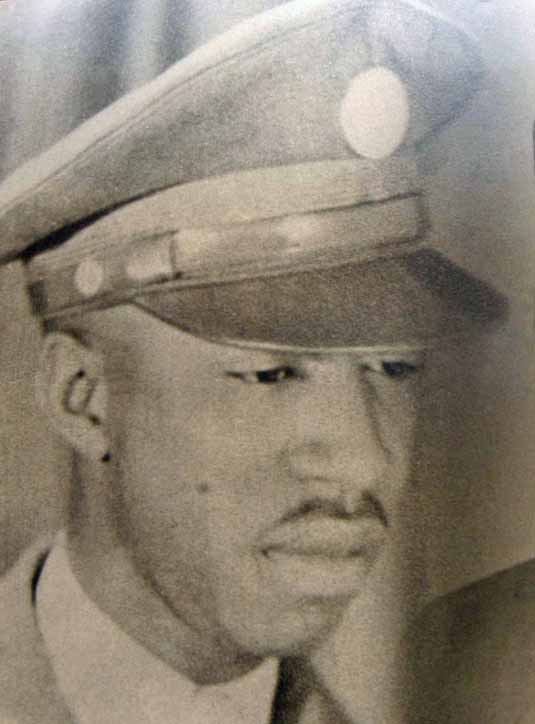

Clyde Kennard

Letter transcribed with original punctuation. Read about Clyde Kennard.

The letters were provided by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH) Sovereignty Commission Collection.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn