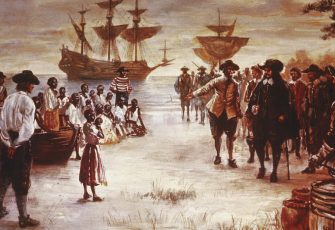

Artist’s imagining of the arrival of Africans to Jamestown, Virginia, 1619. Key’s mother likely arrived by slave ship from the Caribbean or from Africa. Source: Hulton Archive

On July 21, 1656, Elizabeth Key became the first woman of African descent in the North American colonies to sue for her freedom and win.

Key was born in 1630 in Warwick County, Virginia, to an enslaved African woman. Her father was a white planter named Thomas Key. Key was baptized in the Church of England, and, because she was an “illegitimate child,” placed in indentured servitude. Her indenture was transferred to a justice of the peace named John Mottram. In 1650, Mottram paid for the passage of several young English indentured servants. One of them was William Grinstead. Elizabeth and William soon began a relationship and had a son named John.

John Mottram died in 1655, and his heirs designated Key as enslaved, not indentured, and asserted that she and her son belonged to Mottram’s estate. William Grinstead, now free from his indenture and practicing law, represented Key and their son as they sued for freedom from the Mottram’s in court.

Her case hinged on several key arguments. One was the fact that her father, Thomas Key, was English, and that according to English law one’s legal status as free or in bondage followed that of the father. Secondly, she had been in indentured servitude for ten years longer than she should have: Thomas Key had stipulated that she was to be set free when she was fifteen. Finally, she argued that she had been baptized as a child and was a practicing Christian, and therefore should not be enslaved. She lost her case in appeals court, but petitioned the General Assembly to look into her case. A committee was formed to investigate, and they sided with Elizabeth, determining that she was free based on her father’s status and baptism. The following is an excerpt from the committee’s report:

It appears to us that she is the daughter of Thomas Key by several Evidence. […] That by the Common Law the Child of a Woman slave begot by a freeman ought to be free. That she hath been long since Christened […] For these Reasons we conceive the said Elizabeth ought to be free and that her last Master should give her Corn and Clothes and give her satisfaction for the time she hath served longer than She ought to have done.

With this report from the committee, Elizabeth and her son won their freedom in a lower court on July 21, 1656. Elizabeth married William Grinstead and had a second son, but William died soon after in 1660. Elizabeth lived out the rest of her life in freedom with her two sons.

Elizabeth’s victory came at a formative moment in colonial Virginia, as the very concept of whiteness was emerging as a means of reinforcing existing power structures. Through law, white planter elites were regulating and defining slavery through Blackness. As Ibram X. Kendi writes in Stamped from the Beginning, “Elizabeth Key had ravaged the ties that planters had unofficially used to bind African slavery.”

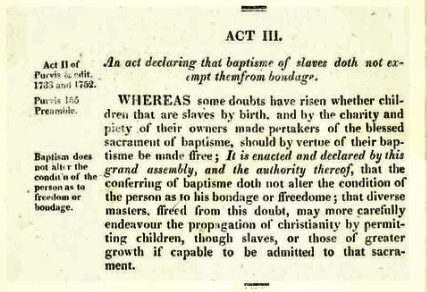

Laws that gave Key her freedom were thrown out in the 1700s by white men who wanted to design a racialized society with statutes like this one, which states “the conferring of baptisme doth not alter the condition of the person as to his bondage or freedome.”

To bind these ties back together, the white planters took action through the Virginia legislature. In 1667, eleven years after the General Assembly played a crucial part in Elizabeth’s victory, the same legislative body passed a bill declaring that the “conferring of baptism does not alter the condition of the person as to his bondage or freedom.” The passage of this law was inspired by appeals for freedom like Elizabeth’s, where enslaved or indentured individuals used their status as Christians to argue that they could not be held in lifelong bondage.

During the colonial era, the system of racialized chattel slavery that in the following centuries was justified as an eternal and biologically based hierarchy was only just beginning to take shape. Slavery as a system in the United States is often studied at its most rigid and fixed. Cases like Elizabeth Key’s help highlight the ways in which justifications for discriminatory practices were built over time, and the fluidity of status and freedom for people of African descent in early colonial Virginia. She initially lost her case because she and her son were classified by the court as “Negroes,” but was able to win by highlighting her father’s whiteness and her Christian faith.

It is essential for students to learn about the actions of figures like Elizabeth Key, because it shows that systems can be unmade, just as they were made. The Zinn Education Project offers a lesson, The Color Line by Bill Bigelow, to teach about how laws were used to divide people of African descent, Native Americans, and poor whites in Colonial America.

Professor Ibram Kendi discusses the case of Elizabeth Key in this four minute Teaching Tolerance key concepts video.

Sources and Related Resources

“Dangerous Woman: Elizabeth Key’s Freedom Suit – Subjecthood and Racialized Identity in Seventeenth Century Colonial Virginia.” (2008) by Taunya Lovell Banks, Akron Law Review.

“Elizabeth Key.” History of American Women, 2019.

Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. (2016) by Ibram X. Kendi.

“Elizabeth Key and Her History-Changing Lawsuit.” (2018) by Jone Johnson Lewis. ThoughtCo.

“Elizabeth Key Grinstead, 1630-1665.” Black Past.

William Waller Hening, Statutes at Large; Being a Collection of all the Laws of Virginia. (Richmond, Va, 1809-23).

Slave Codes, Liberty Suits and the Charter Generation, a Learning for Justice Hard History Podcast with Hasan Kwame Jeffries and Margaret Newell.

This post was written by Hannah Russell-Hunter, an intern with the Zinn Education Project in the summer of 2019 and now a classroom teacher in Virginia.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn