This collection of essays exposes the U.S. Constitution for what it really is — a rulebook to protect capitalism for the elites.

This collection of essays exposes the U.S. Constitution for what it really is — a rulebook to protect capitalism for the elites.

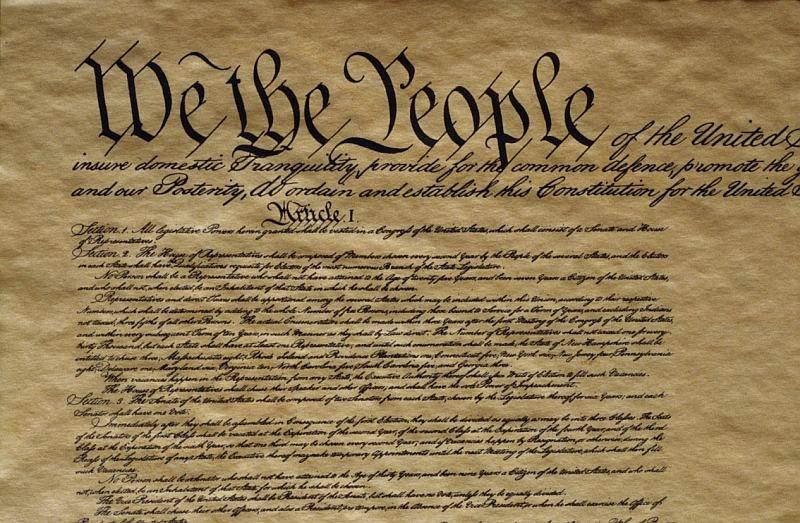

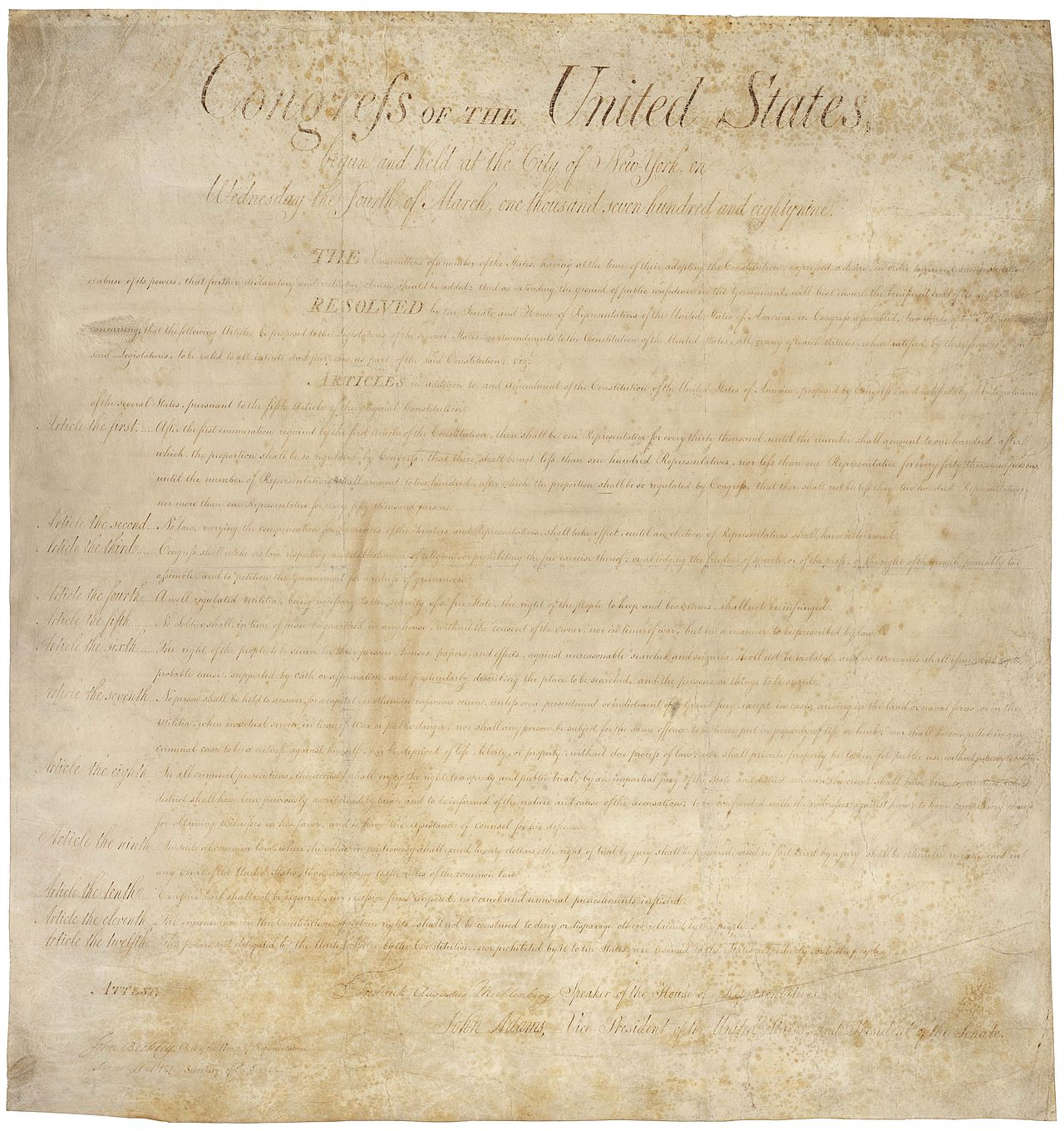

Written by 55 of the richest white men of the early United States, and signed by only 39 of them, the Constitution is the sacred text of U.S. nationalism. Popular perceptions of it are mired in idolatry, myth, and misinformation — many have opinions on the Constitution but have no idea what’s in it.

The misplaced faith of social movements in the Constitution as a framework for achieving justice actually obstructs social change — incessant lengthy election cycles, staggered terms, and legislative sessions have kept social movements trapped in a redundant loop. This stymies progress on issues like labor rights, public health, and climate change, projecting the people of the United States and the rest of the world towards destruction.

Robert Ovetz’s reading of the Constitution shows that the system isn’t broken. Far from it. It works as it was designed. [Adapted from publisher’s description]

ISBN: 9780745344720 | Pluto Press

Excerpts

These excerpts provide an example of the rich history and analysis offered by author Robert Ovetz.

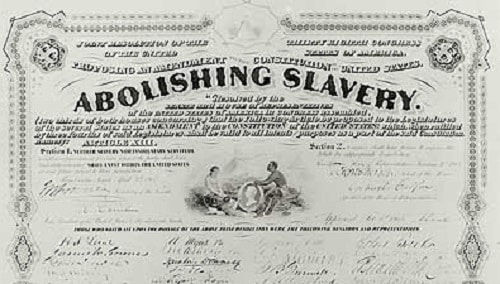

Without the consent of the elite minority, the only remaining way to make change is to force it on them. Forcing them to accept change is the cause of the greatest periods of reform in U.S. history. Universal white male suffrage, the abolition of slavery, Reconstruction, Populist and Progressive Era reforms, women’s suffrage, rights for workers, the civil rights movement, ending the Vietnam War, environmental protections, and rights for LGBT people were not benevolently given but were won by force. (p. 6)

The rules of the Constitution work to diffuse, delay, and dampen change by rendering the system for making change, one of the “inconveniences of democracy” that Madison wanted to avoid, inefficient. Our system of government is mined with countless roadblocks and obstructions that make significant change impossible. The rule of property is protected against economic democracy.

This book examines how the Constitution was intentionally designed — and continues to effectively function — just as the Framers intended: to impede political democracy and prevent economic democracy. The documentary evidence lays bare the purposefully inefficient design of the U.S. Constitution to protect both government and the capitalist economy from democratic control, and how change can only be made by tearing up the rule book and starting over again from the bottom up. (p. 7)

Admirers of the Constitution rarely grasp that the Constitution we have is an eighteenth-century rule book written in secret by 55 white men, of whom only 39 signed, 13 left, and 3 refused to consent to. These 55 achieved what previous plans to control their states and the previous confederation had failed to achieve through elections. These Framers needed a new system that would let those like them write the rules for how we are governed. Divided among themselves along varying competing interests, the Framers unified around the need to leave government to those like them with property and wealth. . .

The Constitution is a rule book written in 1787 that still dictates how we govern ourselves in the twenty-first century. Our world has changed dramatically since 1787, but the Constitution is virtually the same. It is a rule book written by those who distrusted democracy and the people who would wield it, if they were allowed to rule. (p. 18)

If the Framers could be said to have a “vision,” a claim repeated ad nauseam, it is the vision of the need to protect the shared economic interests as the property-owning elites from democracy. Recognition of their shared class interests compelled them to restrain the demands from below with a new federalist system that could check organized movements from democratically controlling the states while blocking the democratization of the economy. They were correcting an oversight — protection for all forms of property — lost during the Revolution. (p. 33)

The Framers designed the Constitution to create a perpetual power of the elite minority to check the will of the majority, a minority check invulnerable to every legal, judicial, and constitutional reform short of a complete constitutional overhaul.

There are not “defects” or “failings” as much as the consequences of an intentional design logic. This was celebrated by Hamilton and Madison, who wished to divide the population so sufficiently that they couldn’t effectively join forces with one another across differing secondary interests. (p. 37)

No part of the Constitution is more misunderstood, misquoted, and over-valued than the Preamble. The courts have mostly shied away from attempting to interpret the short, vague paragraph and apply precedent, Congress and the executive have ignored it almost altogether, and historians and political scientists mostly neglect it. This neglect is in stark contrast with the importance given to it by “We the People,” who use it to understand what the Constitution does and should be doing. The Preamble is distinctly written as a philosophical aspiration rather than in the dry, legalistic style that characterizes the rest of the Constitution. Perhaps this is why the Preamble has grabbed the attention of ordinary people: it expressed what we would like the Constitution to be and do, even though in reality it does something very different. . .

If we examine the meaning of the eight key principles found in the Preamble we find a preface to a set of golden handcuffs constraining political and preventing economic democracy. (p. 40)

It is extremely difficult to reconcile a belief in the Constitution as living, flexible, and changeable with the virtual impossibility of making change in the U.S.A. There is abundant persuasive evidence that the Constitution was designed not to facilitate meaningful systemic change but to prevent anything that does not serve the interests of the propertied elite. Designed to be nearly unchangeable, the Constitution simply cannot be fixed. We have run out of precious time trying to change what was designed to thwart change. . . The constitutional rule of property — made possible by the expropriation of Native peoples, slavery, and the exploitation of labor — is a primary threat to the survival of humanity. (p. 159)

Find related resources below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn