On Jan. 20, 2012, Jay Winter Nightwolf’s weekly WPFW FM 89.3 program, “American Indian’s Truths — Nightwolf — ‘The Most Dangerous Show on Radio’” focused on the Arizona state ruling against the Mexican American Studies program in the Tucson Unified School District and the confiscation of books from Tucson classrooms.

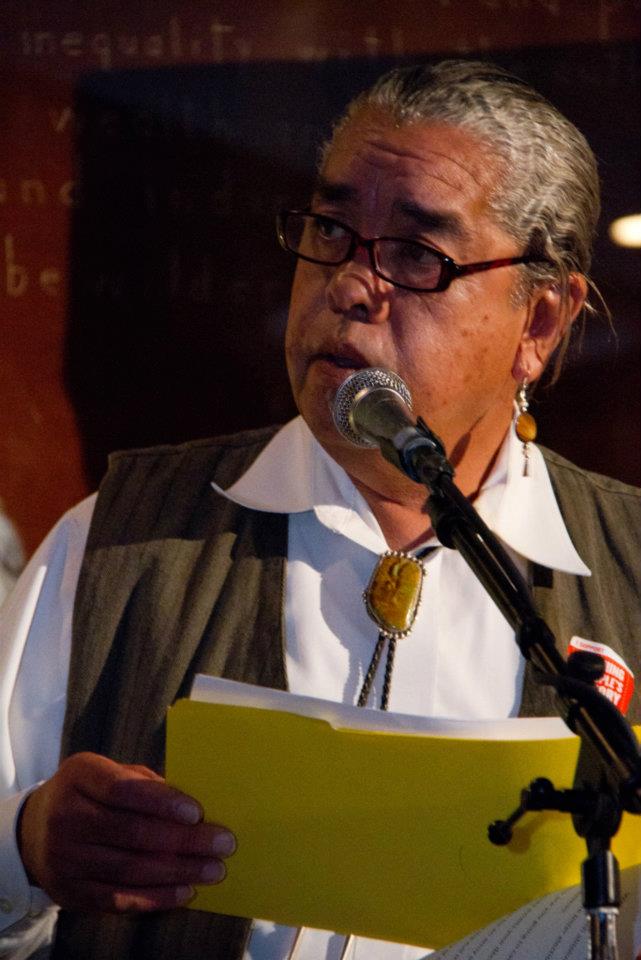

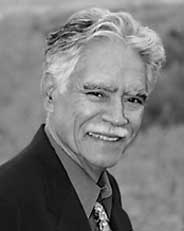

Nightwolf hosted special guests:

- Rudy Arredondo, President of the National Latino Farmers & Ranchers Association

- Dr. Roberto Cintli Rodriguez from the University of Arizona—Tucson

- Dr. Rudolfo Anaya from the University of New Mexico Professor Emeritus Department of English

|

Abbreviated Podcast of the Show

Transcribed Excerpts

Rodriguez

This specific battle began with Tom Horne, the predecessor to Huppenthal. He determined that the culture, the material, the curriculum being taught [in the Mexican American Studies program]…was outside of Western civilization. He has pretty much proclaimed this as a civilization struggle. And it pretty much is! The curriculum is based on 3 concepts and they’re all part of my youth-based philosophy… “You are my other self”… “To speak the root of the truth,” (and at the same time it also promotes social justice), and the third concept . . . pretty much an affirmation that all human beings are, in fact, equal; that we all have a different explanation for the universe, some call it God . . . they don’t always translate. The point being again to reemphasize that we are no better, no worse than anybody else. For that they are accused of promoting hate, racism, and on and on but the reality is the exact opposite.

You have to understand the concept called reduccion. That comes from the 1500s and was part of the Inquisition… We’re going to be inviting all the banned authors here, because this is not something new. American Indians understand the concept of boarding school. This is very similar. The reductión was the same idea: Kill the Indian, create a Christian; create a Western man, a Western woman. The focus, the target, is the indigineity. They’re ok with everything else. It’s like a laser focus on the topic of indigineity. They don’t want that. See, Mr. Horne is very clear on the topic. He says that anything that is not from Western Civilization, anything that does not derive from Greco-Roman culture, should not be taught in Arizona schools. That’s why some people want to fight him about that and say, well wait a minute, we don’t disagree. That is, our culture does begin with maíz, thousands of years ago. All of us on this continent have that heritage too, whether we’re mestizo, whatever, most of us have that heritage, that connection to maíz, and they don’t want that. They want it to be Columbus, they want it to be Greeks and Romans and that’s what this is about. The youngsters know that, they’re little kids and they know it, and they’re not going to give up willingly.

I was talking to one of my colleagues, Norma Gonzalez…I asked her about what was confiscated from her particular classroom and she said, ‘Everything that we’ve ever created since the beginning of the program, which is about 15 years.’ And she said, ‘But you have to understand it isn’t just books, it’s everything.’ And then just as equally important, because a lot of us are emphasizing the books, but it’s not just the books, that’s kind of the byproduct. The primary thing that has happened here is that both the people and the discipline, the curriculum are being dismantled. It was so successful, that’s why it’s being dismantled. The graduation rate was close to 100%, the college-going rate was close to 70%.

Let me tell you about international law… Which is protected by every single human rights treaty and convention ever since World War II… I give the acronym for my students of C.H.I.L.E: That is culture, history, identity, language and education. Every single treaty protects that. And it’s precisely to prevent the physical and cultural genocide of people, and to insure their human rights and their humanity. So at that level we have laws that guarantee that. Those rights we’re born with, nobody gives them to us, but we have international mechanisms, we have courts, federal lawsuits.

I’ve gone to the hearings. I’ve followed the entire thing. The hearings resemble an inquisition. All these books were put on trial. Posters, images, artwork. . . In other words, who would have thought, it’s 2012, but again, they were going item by item… I have to emphasize that that’s kind of the symptom. That is, the effect is all these books being banned, but the real crime is that they have criminalized the knowledge, they have made it invalid, they have told little kids that who they are, their memories, are nothing. That’s not worth anything… They have to be little Greeks and Romans. Imagine that! Being told that what’s foreign is what’s from here, the maíz, but what’s American is from Greece and Rome.

…Of course I’ve always known about the concept of racism, but I think in my own life I instead use a different term, which is dehumanization. I think a lot of us have lived and grown up and known that. It can range…I was almost killed by police… but I think what’s even more oppressive is what’s happening in Arizona. That is, the attempt to wipe out the person. Again, that is what reduccion is, and that’s pretty violent. It’s like you take the body, you take the spirit, you take the soul, and in the end you end up with a shell and you reconstruct it to create something else; a whole different person.

Anaya

I published my first novel, Bless Me, Ultima, in 1972. A year after that, in a school district here in New Mexico, the novel was taken out of the classroom and burned. So I’m kind of an old veterano in terms of being banned and censored. It’s been going on for a long time. The contemporary Chicano movement brought to the forefront our identity, our history, our culture, our heritage, our language. We began to put it in books and put it in the curriculum, and that’s the key right there. We need it in the curriculum because our young people have to know who we are: Our history. And since then, Bless Me, Ultima has been on the banned list of the American Library Association for years… So I’ve been in this struggle and I’ve been fighting for a long time. I’ve written essays against censorship… It’s been there and it’s still there… The key to me as an educator has always been: We need our books, we need our culture reflected in the curriculum of the schools.

Throughout history, communities have demanded a right to be heard, a right to self-dignity, preservation of their cultures. That’s probably what the Black movement was all about, not only about social justice and economic justice. After that the Chicano movement came around and we demanded the same thing. There were the walkouts… We owe a great deal to César Chávez, and to all those poets and writers and muralists and musicians who took on the cause and to us who write books, because the books are the truth. They reflect our community, our culture, our place, our sense of spirituality…

We have some wonderful organizations, including the National Council of La Raza who has wonderful attorneys, who very often with the ACLU will get involved in local problems like this, local censorship problems, and fight directly. There’s another area I think that’s very, very important: Direct action. Occupy Arizona would be great. And that’s dealing with what comes out up front.

There are organizations that before the books ever get to the classroom, censor them. There’s a big organization in Texas and when the textbooks are to be adopted- well you know, the school districts need textbooks- but these organizations will censor what goes in there and make school districts bow to them. In other words, not buy that particular textbook. So we’re being cut off at the gate also.

Discrimination takes so many forms. It can be in your face, it can be subtle…I think I felt it most actually when I entered the university. I couldn’t pronounce words as they should be pronounced and I was a raw recruit, and I persevered. But it’s there in many forms. Again, it’s something we have to be aware of and fight.

The organizing and protest, and showing up where there’s a march, let’s do it. But I get back again to, I guess my pet peeve, and that is: Let’s put the books and the history and our culture and our heritage; the whole mestizaje; in the hands of our young people.

Nightwolf

Very recently racially motivated disenfranchisement of our sisters and brothers and children (of the American Indian) in the state of Arizona, the Mexican American, has become a staunch reality of what it feels like to be discriminated against, based on color and national origin. Arizona school superintendent John Huppenthal, the force and the key player behind the Tucson ban against Mexican American studies has gone a step further by also banning 80 books written by Latino, Chicano and American Indian authors and scholars.

When we look at the racist state of mind of the power brokers in Arizona, John Huppenthal’s actions seem to have been taken from the call of the disorder and racism; Nazi furors’ playbook itself. However this is not the case. Adolf Hitler got his play actions by watching what the United States government did to the American Indian. These acts of terrorism are American home grown acts. Take their history studies from them, confiscate their books and the real Mexican American will hopefully disappear.

Arredondo

Well, it seems to me like it’s a longstanding effort to demean our community and it’s racist. I think it’s something that we have struggled long and hard to try to overcome and obviously, at least in Arizona, it’s gotten out of hand.

Texas history was very demeaning. I have always been an avid reader of just about anything I can get my hands on, and it was in the 1960s that I began to meet up with folks, with César [Chavez], with Dolores [Huerta]… and begin to become very acquainted with our history here in the United States. So I want to express my gratitude to [Dr. Anaya] that you had the courage and the wherewithal to be able to provide those kinds of knowledge to those of us that were kept in the dark.

It’s insulting, first of all. We have struggled for many years in many ways. When I went to school in South Texas I could not speak my language. I was five, six years old and all I knew was Spanish. I was not able to speak my language to anyone during the time that I was in school. So, I have very little recollection of what happened up until I was in 2nd grade.

We will persevere and we have been at this juncture many, many times. You know, I grew up in Texas where they called us spics, so it was in your face. Dealt with it. It got rather confusing when I came to Washington, because the dehumanization is very subtle.

Thanks to Jozi Zwerdling, Zinn Education Project intern, for the transcription.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn