The following This Day in History post is excerpted from Brandy Colbert’s 2021 book Black Birds in the Sky: The Story and Legacy of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

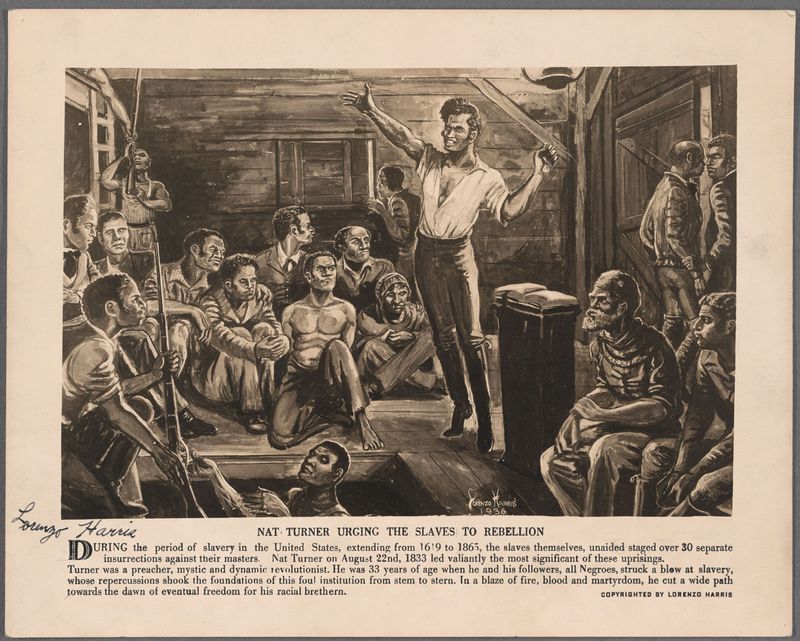

Although some historians claim that the Indigenous people who enslaved Black people treated them more as indentured servants — a fixed term of slavery in which the enslaved often retained some rights — enslavement is enslavement. They were not free, nor were they treated as if they were free, as evidenced by the Slave Revolt of 1842, the largest rebellion of enslaved people in Indian Territory history.

Although some historians claim that the Indigenous people who enslaved Black people treated them more as indentured servants — a fixed term of slavery in which the enslaved often retained some rights — enslavement is enslavement. They were not free, nor were they treated as if they were free, as evidenced by the Slave Revolt of 1842, the largest rebellion of enslaved people in Indian Territory history.

On November 15 of that year, more than two dozen enslaved people in Webbers Falls, Oklahoma, decided enough was enough. At the Joseph Vann plantation, the enslaved waited until sleep had settled over the farm, then locked the slaveholders and overseers — supervisors who ensured the enslaved people “stayed in their place” — in their homes. The enslaved Black men, women, and children took all kinds of things that would help execute their rebellion: horses and mules, guns and ammunition, food, and other supplies. At sunrise, they headed out on their journey, stopping to pick up more enslaved people in Muscogee (Creek) Nation. The destination? Mexico, where they would be free.

Their trek was not without incident; at one point, the escapees fought Cherokee and Muscogee (Creek) pursuers, a battle that ended with two enslaved people dead and twelve captured. The rest of the group traveled on, managing to defend themselves against a duo of slave hunters in the Choctaw Nation — ultimately killing them. But, unfortunately, the story does not end with their freedom: Although nearly forty people had joined the rebellion, they were eventually outnumbered by their pursuers. Two days after the escape, the Cherokee National Council, afraid that word of their rebellion would spread and influence other enslaved people to revolt, approved a Cherokee militia of eighty-seven men, whose mission was to capture the fugitives and bring them back home. The runaways eventually lost their way and were caught by the militia near the Red River on November 28, after nearly two weeks on the run.

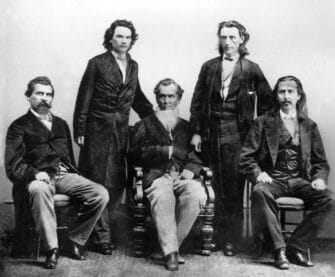

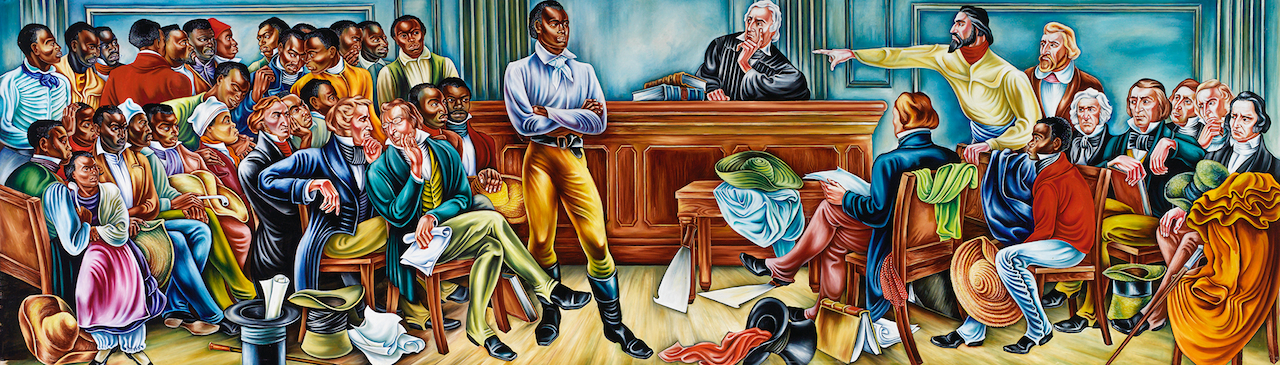

Cherokee delegates to the U.S. Congress in Washington, D.C., 1866. Left to right: John Rollin Ridge, Saladin Watie, Richard Fields, Elias Cornelius Boudinot, and William Penn Adair. Source: Getty Images

The remaining rebels were shuttled back to Webbers Falls in early December. Five of them were given a trial, found guilty of the two murders in Choctaw Nation, and executed. The rest of the group was sent back to their slaveholders. The Cherokee people believed the rebellion was sparked by free Black Seminole people, who were armed and lived nearby at Fort Gibson, and so shortly after the runaways were caught, the Cherokee Nation passed “An Act in regard to Free Negroes,” which forced all free Black Americans, with the exception of those who’d been formerly enslaved by the Cherokee people, to leave Cherokee land by January 1, 1843.

After the American Civil War ended in 1865, all enslaved people in Indian Territory were finally given their freedom; additionally, the Native Nations were ordered to provide land to the newly freed Black people. And from there, Black Oklahomans began to start businesses, and also purchased farmland.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn