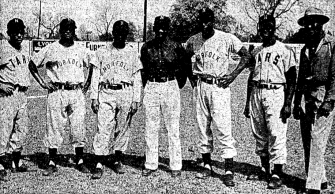

In 1954, these six players, pictured with their trainer, became the first Black men on the Tars’ spring training roster. Source: The Sumter Daily Item.

On April 7, 1954, African American baseball fans in Norfolk, Virginia, scored a doubleheader victory by getting the Norfolk Tars minor league team to desegregate both the club’s roster of players and stadium seating for the first time.

The actions were achieved by a successful boycott of the 1953 season’s home games and a 1954 preseason meeting between representatives of Black baseball fans and the new executives of the Norfolk Tars, which was the Class B minor league affiliate of the powerful New York Yankees.

In that historic April game, an exhibition between the Yankees and the Tars, 19-year-old Ed Andrews, the first African American to pitch for the Tars, hurled three scoreless innings against the Bronx Bombers in his debut.

After the game, sports columnist Cal Jacox wrote about the stadium’s new integrated seating in the April 17, 1954, edition of the Journal and Guide, a weekly newspaper that focused southeastern Virginia’s African American community. In his celebratory piece, he wrote:

An overflowing throng of an estimated 8,000 fans experienced the simple act of colored and white fans entering the same gate and . . . sitting together in the same sections.

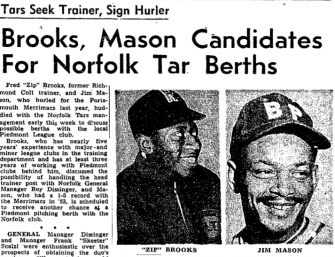

In February 1954, news circulated about new hires, including “Zip” Brooks and Jim Mason. Source: Norfolk Journal and Guide.

There was a reason to celebrate. The integrated team and stadium of April 1954 stood in stark contrast compared with the apartheid conditions before that season. Before then, the players were all-white and the stadium was segregated, with inferior seating and standing room only for non-white fans. These conditions led to the season-long 1953 boycott of the Tars.

The protest began when African American fans decided they were “fed up” with the Jim Crow treatment they had received for years at Myers Field, home of the Piedmont League Norfolk Tars, Jacox wrote on April 10, 1954. Instead of going to Myers Field, many Black fans in the Norfolk area took their love of baseball across the Elizabeth River to watch the rival Portsmouth Merrimacs or across the James River to see the Newport News Dodgers. Both of those teams already had integrated on the field and in the stands.

The Norfolk boycott was one of many civil rights activities aimed at minor league teams for several years after Jackie Robinson had integrated Major League Baseball in 1947, according to Bruce Adelson, author of Brushing Back Jim Crow: The Integration of Minor-League Baseball in the American South. While Robinson had broken the big-league color line, dozens of farm teams, especially in the South, continued to resist. Not only did they not play Black athletes, but they humiliated African American fans by making them go through separate ticket gates and sit in inferior seats at minor league stadiums, Adelson wrote.

The desegregation of minor league teams and stadium seating had a broader impact beyond baseball. U.S. Representative John Lewis of Georgia, said that baseball created “the climate, the environment, and set the stage for other walls to come tumbling down.”

As newspaper columnist Jacox wrote in April 1954, it was “democracy in action.”

By Michael Knepler, who prepares periodic #tdih posts for the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn